I spent last week at my brother’s. While my son frolicked with his cousins, I raided my sibling’s library. So here’s a series of brief reviews:

Barefoot Gen, Volume 1 by Keiji Nakazawa A story of world-historical import and great human tragedy is always improved by warmed-over melodrama, poignant irony, and random fisticuffs. Stirring speeches about the horrors of war are feelingly juxtaposed with scenes of anti-militarist dad beating the tar out of his air-force-volunteer son. On the plus side, though, drill-sergeant brutality set pieces are apparently the same the world over. Also, to give him his due, Keiji Nakazawa stops having his characters beat each other up for no reason every third panel once the bomb drops. Tens of thousands of civilians running about shrieking as their flesh melts is enough violence for even the most impassioned pacifist adventure-serialist. It’s okay to have Gen rescue the evil pro-war neighbors from their collapsed house and to have the evil pro-war neighbors refuse to help dig out Gen’s family and to have the sainted Korean neighbor help carry Gen’s mom to safety as long as you don’t have Gen and the Korean pummel the evil pro-war neighbors with a series of flying kicks as the city burns. It’s all about restraint.

Barefoot Gen, Volume 1 by Keiji Nakazawa A story of world-historical import and great human tragedy is always improved by warmed-over melodrama, poignant irony, and random fisticuffs. Stirring speeches about the horrors of war are feelingly juxtaposed with scenes of anti-militarist dad beating the tar out of his air-force-volunteer son. On the plus side, though, drill-sergeant brutality set pieces are apparently the same the world over. Also, to give him his due, Keiji Nakazawa stops having his characters beat each other up for no reason every third panel once the bomb drops. Tens of thousands of civilians running about shrieking as their flesh melts is enough violence for even the most impassioned pacifist adventure-serialist. It’s okay to have Gen rescue the evil pro-war neighbors from their collapsed house and to have the evil pro-war neighbors refuse to help dig out Gen’s family and to have the sainted Korean neighbor help carry Gen’s mom to safety as long as you don’t have Gen and the Korean pummel the evil pro-war neighbors with a series of flying kicks as the city burns. It’s all about restraint.

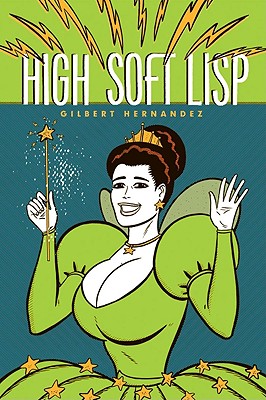

High Soft Lisp by Gilbert Hernandez

High Soft Lisp by Gilbert Hernandez

Hernandez tells us several times over the course of this searingly human graphic novel that his protagonist, Fritz, has a genius level IQ. And how would we know if he didn’t tell us? Also, she was probably sexually-abused as a child, and therefore the fact that she fucks anything that isn’t nailed down is a sign of her profound psychological thingy, and not a sign that Hernandez likes to draw balloon-titted doodles fucking everything that isn’t nailed down. In this, of course, the comic is profoundly different from past works like Human Diastrophism, in which there were big tits and gratuitous fucking, but interspersed with paeans to the human interconnection of all of us who are bound together by empathy and profound meaningfulness and also by a love of big tits and gratuitous fucking.

Whoa Nellie! by Jaime Hernandez If you adore female Mexican wrestling and girls’ fiction about the ups and downs of friendship — then I still can’t really see why you’d want to read this.

But, you know, it’s “fun” and “enthusiastic”. “Buy it now.”

Ghost of Hoppers by Jaime Hernandez Alternachicks drift through their alterna-lives with quirky poignance and poignant quirkiness. Plus, bisexuality.

To be fair, to really understand the subtle characterizations here, you need to take the entire Hopey/Maggie saga and inject it into your eyelids weekdays 8:30 to 5:30 and weekends 12-6. Only when you’re blind and destitute and wretching blood in the sewer with the ineradicable taste of staples glutting your tonsils will you truly understand the blinding genius of layered nostalgia.

Cool It by Bjorn Lomborg Better than the movie Lomborg argues convincingly that it would be better to cure malaria and HIV than to wreck our economies by failing to reduce greenhouse emissions. Which largely confirms my suspicion that global warming is less a real policy priority than it is an apocalyptic fad — a rapture for Prius-owners.

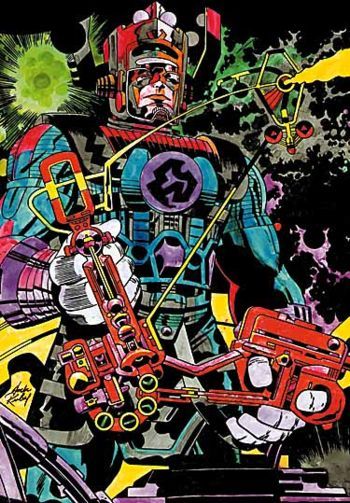

Marvel Masterworks: Jack Kirby There’s been a lot of debate in comments here as to whose prose is more tolerable, Stan Lee’s or Jack Kirby’s. After trying and failing to read the Marvel Masterworks volume, I think I have to say, who gives a shit? Lee’s hyperbolic melodrama is slicker and Kirby’s more thudding, but the truth is that if you put the two of them together in a room with an infinite number of monkeys and a typewriter and gave them all of eternity you’d end up with a pile of monkey droppings and a lot of subliterate drivel. The ideal Jack Kirby would be a collection of his illustrations of giant machines and ridiculous monsters and weird patterned backgrounds with all the dialogue balloons excised. Short of that, you look at the pretty pictures and you try your best to skip the text.

Captain Britain by Alan Moore and Alan Davis It’s hard to believe anyone was willing to publish such an obvious Grant Morrison rip off, but I guess comics are shameless like that. It’s all here with numbing inevitability — the multiple iterations of our hero (Captain U.K. of earth 360b, Captain Albion of earth 132, etc. etc.), the goofily foppish reality altering villain, the cyberpunky organic/computer monster. Throw in a standard kill-all-the-superheroes plot and a bunch of high-concept powers (abstract bodies! summoning selves from further up the timeline!), add some borderline-satire of the square-jawed protagonist and you’ve got everything Morrison’s written for the last two decades. To be fair, though, Moore and Davis seem to be on top of their derivative hackitude, and as a result there’s none of the pomposity that can infect their prototype. Captain Britain doesn’t die for our sins and he isn’t an invincible icon; he’s just some dude in spandex swooping through the borrowed plot with equal parts bewilderment and bluster. Sometimes imitation works better than the real thing; maybe Morrison should try ripping off these guys next time.

The Defense by Vladimir Nabokov Nabokov’s characters sometimes seem more like chess pieces than like people; Nabokov pushes them here and pushes them there about the page, forming patterns for his own amusement. There’s no doubt that it is amusing, though, and while I don’t pretend to understand all the ins and outs of the game, I enjoyed watching the patterns expand and dilate, moving in black and white through their silent hermetic dance. There’s one passage, which I wanted to copy out but now can’t find again, in which our protagonist, the corpulent, hazy chess master Luzhin, types a string of random phrases at the typewriter and then mails them to a random address from the phonebook. If any book makes me laugh that hard even once, I consider myself well-recompensed for my time.

The Real the True and the Told by Eric Berlatsky Eric printed an excerpt of his book on HU here, but I hadn’t gotten a chance to read the whole thing till now. Despite his daughters’ review (“Why are you reading Daddy’s boring book?”) I really enjoyed it. The basic thesis is that post-modern texts like Graham Swift’s “Waterland” or Rushdie’s “Midnight’s Children” don’t actually deny the reality of history. That is, history in such works is not just text. Rather, postmodern lit tries to approach the real through non-narrative means. The emphasis on the textuality and artificiality of historical narratives is a way of reaching through those narratives to reality, not a way of denying the existence of reality altogether. Basically, for Eric, post-modern fiction rejects, not reality, but simplistic narrative, suggesting that the first can only be accessed by rejecting or resisting the second.

I think it’s a convincing argument about the goals of post-modern fiction, though I question whether the tactic is as successful as Eric seems (?) to want it to be. There are two problems I see.

First, as Eric’s book kind of demonstrates, the anti-narratives and non-narratives Eric discusses are themselves, at this point, narrative tropes. When Artie in Maus laments the insufficiency of narrative, for example, he’s voicing long-standing clichés intrinsic to accounts of the Holocaust; when Kundera talks about Communists rewriting history, he’s voicing long-standing clichés about totalitarian regimes which go back to Orwell, at least, and probably before him. Self-reflexive, alternative narrative structures are their own genre at this point…they’re well-established narrative traditions in their own right. It’s hard for me to see, therefore, how those narrative traditions really effectively escape their tropeness and encounter the real in a way that’s diametrically opposed to the way that more traditional narratives encounter the real. Which is to say, Eric’s argument seems to be that the Book of Laughter and Forgetting is through its form closer to the real than Pride and Prejudice — and I don’t buy that.

The second problem I have is that the real in many of these books (and in Eric’s discussion) ends up being linked to trauma. The Holocaust and pain and suffering is more “real” than love or marriage. Eric also notes that the quotidian, or unnarrataeable is often figured as the real too…which would mean that the real is either trauma or boredom. I’m as pessimistic as the next Berlatsky I think, but I’m not really sure why bad or neutral is more real than good.

Which brings me to my second second (and last) problem…which is that I think it’s quite difficult to theorize the real without theorizing the real. Or to put it another way, can you talk about the real while bracketing theology? If you’re at a place where the real is either the Holocaust or tedium, it’s hard to see how exactly that’s different in kind from nihilism — and if you’re a nihilist, what are you doing talking about the real in the first place?

Anyway, the book was great fun to argue with, and probably the thing I read on vacation that I most enjoyed. It’s amazon page is here in case you want to raise the fortunes of the extended Berlatsky family.