(Note: Please excuse the regrettable patched scans)

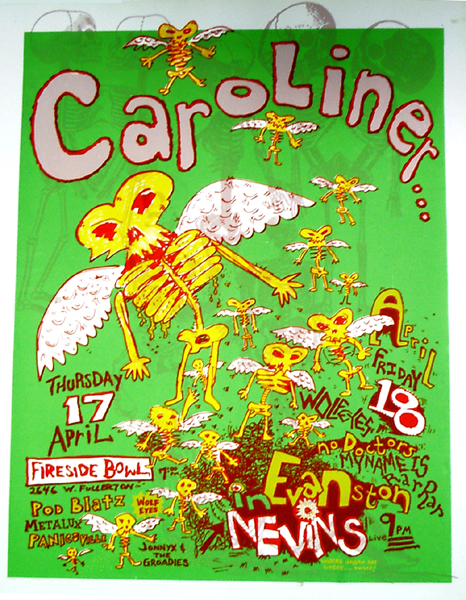

As someone who has worked on adventurous gritty lo-fi publications that are both free and priced, my experience is that, after some period of time of unsold boxes sitting around in your basement, the priced publications will become free. Which is why the recent revival of Chicago’s free Lumpen magazine is both an exciting development and an astute choice, and why a full-color comics issue is even more astutely exciting. The recent local success of collective celebrations of sequential creativity like Trubble Club and Brain Frame, and free-comics forebears Skeleton News and The Land Line, make it a great time for a newspaper and an art show glorifying the bipolar neurotic introspective banality and frantic psychedelic randomness of the underground aesthetic.

My preference, without question, is for the trippy-manic end of the spectrum, which is well-represented in this issue and exhibition. The perverse results of combining images with narratives (not that it’s a new thing) results in confusingly coded explosions of energy, from the Choju-Giga Scrolls to Little Nemo to Superman to Jack Kirby. Speaking of whom, Anya Davidson manages to carve out a unique niche in the collection with a page of vivid, klunky yonic-symmetrical panels of gendered monstrosity that borrow from equal parts Kirby and Gary Panter. While opting for a more spare and bold design sensibility than either of those two, Davidson’s simple meditation on difference is lent some creepy weight by the smudgy nonspecificity of a bygone comics era.

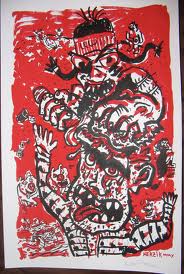

Along with Marian Runk’s and Keith Herzik’s dazzling contributions, the least narrative work in the collection might be Ryan Travis Christian’s hallucinogenic splash-page monochrome miasma of ghosts and pinwheels, supplemented by three panels of lysergically widening pupils being approached by a finger. The piece, like much of Christian’s work, reads like a disorganized scrapbook of Dumbo’s alcoholic nightmare, if it were a syncopated tale of undead minstrel vengeance conceived by Max Fleischer, director of the early shape-shifting Popeye and Betty Boop cartoons.

The polemic standout of the show was Coughs’ co-founder Carrie Vinarsky’s tribute to Super Storm Sandy, a scribbly stripper-cyclone hurling obscenities simultaneously at her human victims and progenitors like Lindsay Lohan on a bender and armed with crayons, while her giant vagina rains down mayhem on hapless Manhattan.

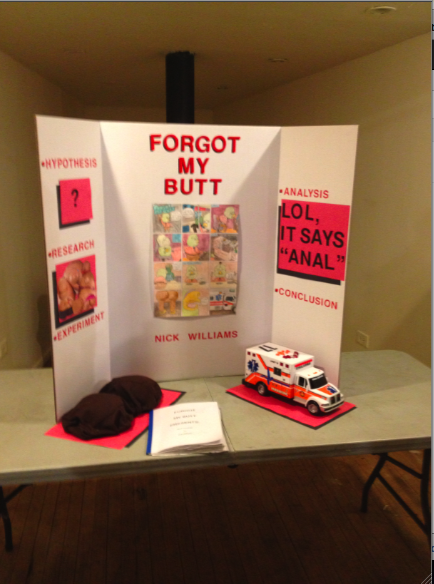

But perhaps the most memorable comic is, ironically, an ode to forgetting. In particular, to forgetting one’s own butt. Not satisfied with merely creating a poignant pastel vignette on the trauma of bottomlessness, Nick Williams also put together an incredible little half-assed (as ‘twere) science-fair display for the exhibition on the rigorous process of controlled testing that led to the groundbreaking butt-forgetting result. Sort of a Paper Rad knockoff of a Vonnegut ripoff of Kafka, this delightful fable implicitly mocks any appreciation of its genius. Which is quite refreshing, given underground comics’ knee-jerk reference for faux-Beckett-esque existential wankery.

In all, all free publications, but in particular this free publication, provide one of the few tangible artifacts of a time of universal and ubiquitous dissolution of aesthetic hierarchies (or even preferences), and the Lumpen comics issue is also an entertaining and visually appealing recyclable echo of coffee-table compendia a la Kramer’s Ergot. The future of analog picture-making techniques and physical formats are, I hope, not tied to the nostalgic conservatism of literary authenticity fetishism, but moving more and more into nonsensical eye candy and anti-poetic spouting. These are what images do best.