Earlier this week I wrote a post at the Atlantic where I talked about the game Desktop Dungeons and how its creators had discovered that, in order not to be sexist, they had to work really hard at it. The intention to be non-racist/non-sexist isn’t enough, because the default tropes used to imagine fantasy game settings and characters are racist and sexist. It takes imagination and effort to overcome that.

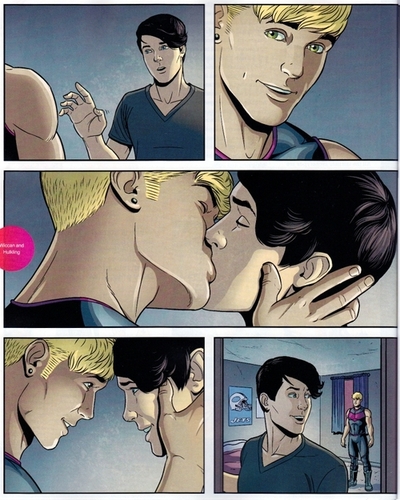

So Kieron Gillen and James McKelvie definitely deserve credit for the extent to which Young Avengers pushes back against decades of accumulated superhero whiteness and sexism. The team includes a gay couple (Wiccan and Hulkling), and a Hispanic child of a lesbian couple (Miss America),along with two other white guys (Marvel Boy and Kid Loki) and a white Hawkeye).

Perhaps more importantly than their numbers, the marginal characters aren’t treated as marginal or other or weird…and the decision not to treat them as marginal or other or weird is nicely linked to the supehero milieu. Hulkling is a green-skinned shapeshifter from another planet; Miss. America is a brown-skinned superhuman from another dimension. Hawkeye is sleeping with the alien Kree Marvel Boy, Wiccan is sleeping with the alien Skrull Hulkling. Amidst all the intricate incoherence of the Marvel multiverse (which Gillen and McKelvie gleefully toss about without much explanation for novices), a non-White superhero as the strongest member of the group or a gay romance as part of the proceedings hardly seems worth mentioning (except, in the later case, as a vehicle for the requisite quotient of intra-team melodrama.)

So Gillen and McKevie set the worthy goal of not being sexist, racist assholes, and they followed through with intelligence and some subtlety. Thus, the comic is good. QED.

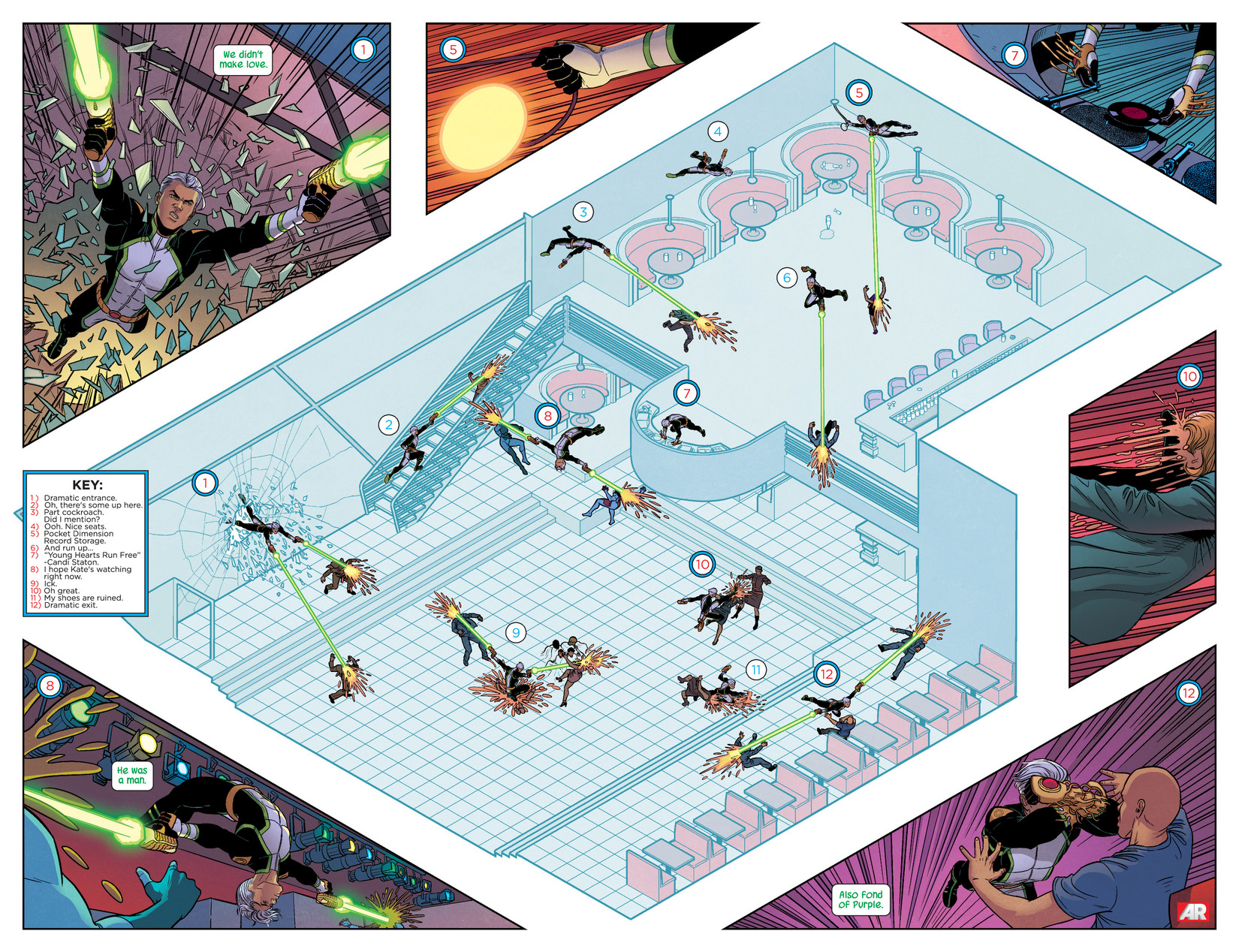

Alas, would that it were so. Not being racist and sexist is hard work, but there are other bits of making a worthwhile piece of art too, and as regards them Young Avengers is less successful. In particular, the artist Jamie McKelvie is, even in the context of crappy mainstream super-hero art, not really any good. His figure drawing is clumsy and haphazard; his poses are stiff when they’re not default; his faces are not particularly distinguishable. But where he is really abysmal is in his layouts, which are consistently confusing and cluttered. Especially in his fight sequences, it’s often almost impossible to figure out what’s happening — and there’s no visual panache (as in say Bill Sienkiewitz) to justify the incoherence. A Chris Ware inspired page is almost laughably incompetent, with tiny figures boucning around in an ugly floorplan that manages to be at one and the same time bulbous, blocky, and boring, the whole thing ringed by uninspired mainstream action sequences, the color scheme of which contrasts garishly with the wannabe-Ware floorplan pastels. Descriptions of the action are set off in a kind of map legend and keyed to numbers because diagrams are what the latest hip comics artists are doing and McKelvie would like to be up to date and hip with all his heart. It’s sort of sweet, if you cover your eyes and don’t look.

Gillen is more competent than that; his dialogue is fun and snappy and pop-culture-aware in a way that seems, if not precisely true to teens, at least true to the sorts of things teens might read. When Kid Loki asks Ms. America why her former super-team broke up and she says, “Musical differences,” I snickered. Same when Hawkeye comments that she knew there was some world threatening catastrophe because Wiccan wasn’t answering his texts every 30 seconds. It’s not genius or anything, but it’s cute. If I can appreciate Taylor Swift, there’s no reason I can’t appreciate this too.

There’s some perhaps interesting thematic material as well, if you squint. We first meet Hulking when he’s shape-shifting in imitation of Spider-Man, hunting down bad-guys as Marvel’s most popular superhero. Later, Wiccan summons Hulking’s dead mother from another dimension…only it turns out to be a shape-shifting soul-eating demon. The other Young Avengers’ parents also end up coming back from the dead as evil glop. You could see the comic then, perhaps, as being about children turning themselves into their parents — or about the way that it’s not just parents who make their kids, but kids who make their parents. The evil parents and the clueless parents (adults can’t see the evil demon mommies) could be a version of the hippie “parents just don’t understand/anyone over 30 can’t be trusted” meme. But you could also see the bad/clueless parents as constructs or dreams — as make-believe parent kids want to/need to create in order to make their own lives. That’s underlined by the fact that the evil parents are the reason for the team coming and staying together; the threat is what makes the book diegetically possible.

Gillen doesn’t ultimately do all that much with this material though. There isn’t, for example, any real anxiety around the evil parents per se — dead moms and dads come back from the dead, but their kids don’t seem much traumatized, or even disturbed. They just trundle on through the by-the-numbers superhero battles, the only real emotional tension being the frustration caused by the fact that, based on McKelvie’s drawings, you can’t actually follow those superhero battles at all.

To some degree that’s fine; it’s a competent empty-headed superhero adventure with crappy art, and it doesn’t make much pretense to being anything else. But, inevitably, the mediocrity of the execution has implications for the treatment of gender/sexuality/race as well. McKelvie, for example, tends to draw the usual slim/hot female characters — he certainly doesn’t feel anything like Desktop Dungeons’ commitment to imagining women who don’t look they walked out of Cosmo. The full-length, blank-faced, hip-cocked, wait-let-me-stuff-this-cleavage-in-somehow Scarlet Witch is an especial low-point.

In a similar vein, Gillen’s insistently shallow writing makes it hard for him to do much with his diverse cast other than have them there. As I said, part of the joy of the comic is that difference is simply treated as normal, so that green skin isn’t much different from brown skin. But while that’s refreshing, it also can feel like a cop out. Is Miss. America really even a Hispanic character, for example, when she’s an advanced human from another dimension who has never experienced prejudice? G. Willow Wilson’s Ms. Marvel deliberately explores what it would mean for a Muslim girl to gain superpowers in terms of her perception of herself and others perceptions of her. Such subtlety is utterly beyond Young Avengers.

So, basically, making art that isn’t mired in stereotypes is hard. And making art that’s good is hard. And those two things put together are even harder, not least because, to some not insignificant degree, you can’t do one without the other.