The tragedy of Killing and Dying isn’t that the collection is focused on hopeless men and their supportive spouses. Rather, it resides in the fact that Adrian Tomine hasn’t produced a comic of any real significance in years; perhaps over a decade. He is, for all intents and purposes, living on past glories, now precariously holding on to that faint promise of a youth filled with sketches drawn from an affable and compassionate realism.

Kim O’Connor is correct in suggesting that Killing and Dying doesn’t showcase a ‘complete’ writer. If an artist finds himself utterly incapable of inhabiting and recreating the life of women he might, with the years, drift away from such representations. This seems to be the case with Tomine even if there are notable exceptions to this in his oeuvre. He was, of course, drawing long form nominally women-centric stories since as early as 1996 in “Dylan & Donovan” (from Optic Nerve #3), a typically morose but trivial tale of two sisters navigating sibling rivalry and a comic convention.

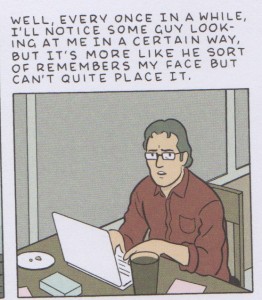

The early Optic Nerves were characterized by workmanlike tales of loneliness, ennui, and urban paranoia. The influence of Jaime Hernandez and Daniel Clowes was worn proudly, and the author’s calling card in those days seemed to be melancholic depictions of young love and relationship dramas, a topic which he revisited with some variations in 2007’s Shortcomings; here mildly enlivened by a foray into the sexual proclivities and hang-ups of Asian American males.

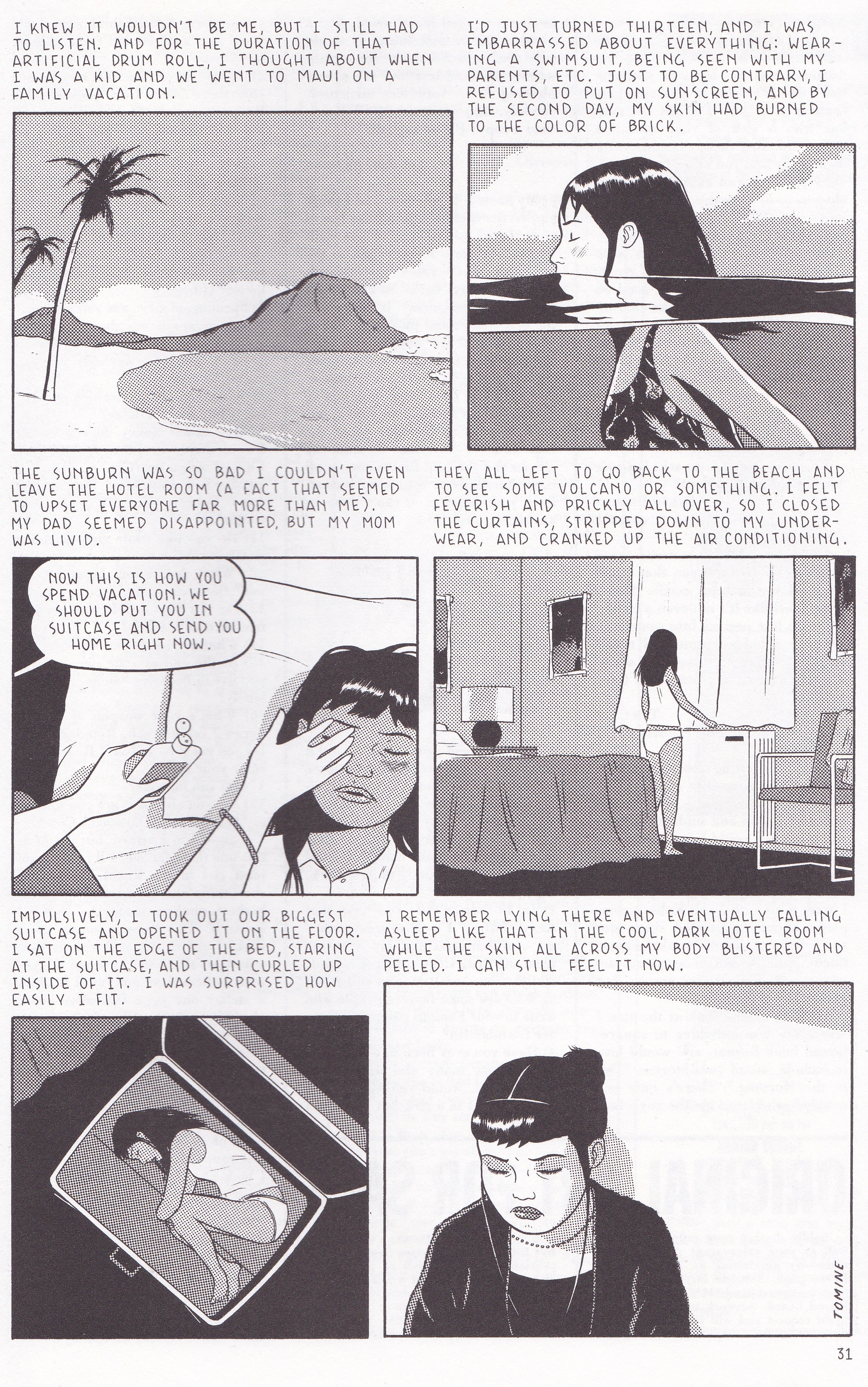

The high point from that period was probably “Hawaiian Getaway” from Optic Nerve #6 (1999), a story which refines and assembles Tomine’s themes into a satisfying whole.

Is Hilary Chan from that story a recognizable female human being or the kind of misanthrope (with a sex-change) so beloved of the alternative cartoonists of the late 80s and 90s? I’d say probably a bit of both. The Asian parental nagging she experiences is familiar but entirely plausible, as is Hilary’s reticence. This study of loneliness seemed groundbreaking for the young cartoonist at the time but now appears somewhat less epiphanic. Nor does it now carry the weight of expectation, for where others artists of his generation appear to have settled back into the comfortable settee of the cartooning gerontocracy, Tomine has largely remained in the background—a “known” artist who really doesn’t have any central work to his name. This despite being regularly included in various “best of” and bestseller lists over the years.

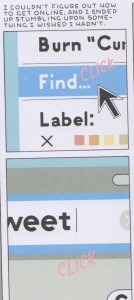

“Hawaiian Getaway” is filled with the juxtapositions which inform so much of Tomine’s work. Chan is a phone operator for a mail-order clothing company who finds it nearly impossible to open up in physical interactions. When fired from her job in the opening pages of the comic, she turns to telephones and other electronic devices to vent her frustrations and translate-record moments of intimacy. Almost all of her aggression, sadness, and distress is communicated through one end of a receiver. The phone device is obvious without being distracting; the ending filled with a kind of foreboding hopefulness; the significance of the story’s title hinted at but with a touch of ambiguity; a layered portrait of a person with an affinity for solitude which is at odds with the demands of modern human existence.

The merits of this story present a harsh reminder of the variable and uncertain trajectory of art and an artist’s career, especially when compared to the dry and ineffectual works which fill the pages of Killing and Dying.

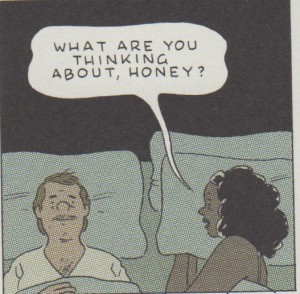

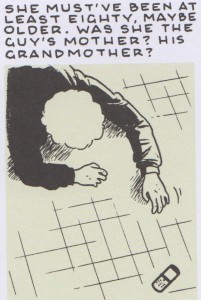

The title story of the new collection is composed on repetitive 4×5-panel grids to add a quick fire rhythm to the exchanges between the members of the family, and to mimic the repartee of a stand-up comic. The symmetry of the layout of these pages is meant to create connection and meaning between both the home and the stage—to forge tension between the unspoken tragedy of a mother’s sickness and death, and the act of dying on stage; the stunted family conversations alternating with acerbic comedic one-lines.

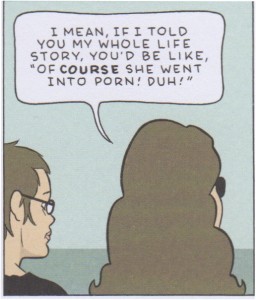

The daughter (Jesse) “kills it” on stage during her amateur comedy night just as (one assumes) cancer and chemo is killing her mother. The absent (presumed dead) mother of the latter half of the story is played alongside Jesse’s own failings at improv. At every point we see the husband-father’s failings, his helplessness in the face of both physical and artistic ruination, a portrait of the rigidity of old age and the tenacity of youth (and in some respects women). The half-figure drawings which populate the panels seem alienated from reality, as if watched from a height like the intentionally gridded floor plan which closes the story. The approach is playful yet academic; the effect devoid of emotion.

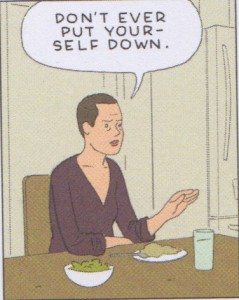

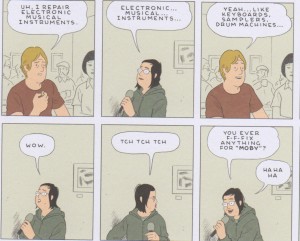

As in the first story of the collection, “A Brief History of the Art Form Known as ‘Hortisculpture'”, Tomine’s rather enervated formalism seems to drain rather than instill meaning. In “Hortisculpture”, the gentle use of comic strip formalism is used to evoke the familiarity of the daily punchline but here tied with the bitterness of failure or perhaps existence in general (an approach widely used in Daniel Clowes’ Wilson). The vignettes are slight and might be seen as Tomine’s attempt at kind of levity which he is hardly known for or at least poorly practiced at. The artist’s benevolent attitude towards his characters, his kindly yet pensive hand when etching out their lives, is a poor fit for the strictures of the “weekly” strip. It has neither the harsh abruptness of Clowes’ Wilson (which I account a failure) or the tender simplicity of Frank King’s Gasoline Alley. The figures remain unrealized ciphers of no consequence filling us with neither disgust or compassion.

It should be noted that the overriding failure of most of the dramas in Killing and Dying is as much that of narrative finesse as that of plot. The barest of plot informs the best story from this collection, yet in leaving completely his comfort zone of insistent dialogue, Tomine manages to achieve something which stands out quite starkly.

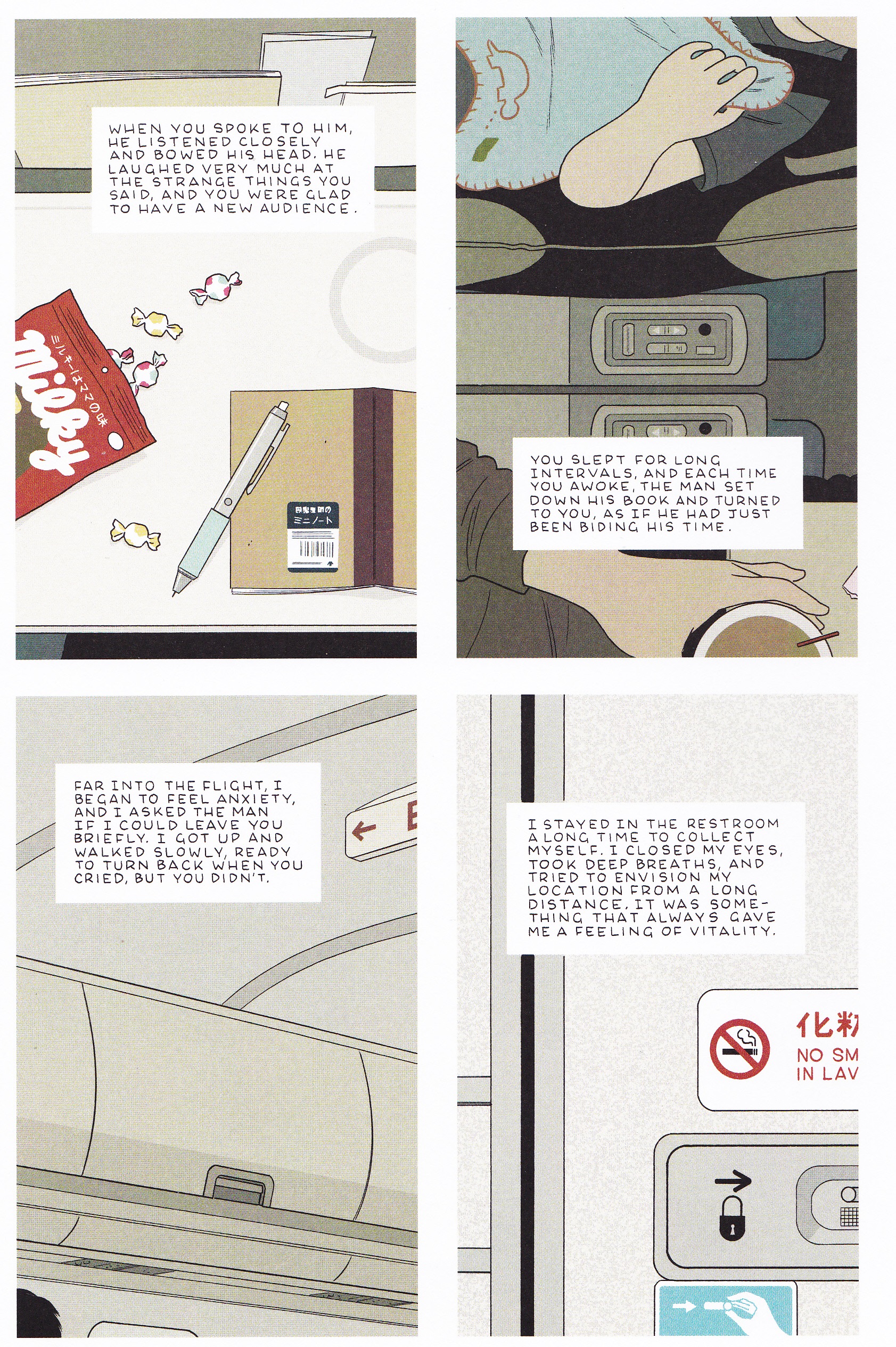

“Translated from the Japanese” begins with the opening page of a journal written in Japanese script, the translation of which marks the first page of Tomine’s illustrated story. We see this journal again turned faced down on an airplane tray 3 pages into the story proper, a ballpoint pen resting on its back cover, this information apprising us that the entry we are reading was written very close to the moment. The impact and meaning of the narrator’s emotions and actions are thrust on to seeming abstractions and inconsequential objects which drift into her line of sight: her anxiety is connected to a storage cabin; her solitary meditation to a lock on a lavatory door; an ambiguous and conflicted reunion to two symbolic bags on a carousel.

This story of only 8 pages is broken up at three points by long establishing shots of the Tokyo skyline, a tranquil depiction of commercial airliner in flight, and a nightscape of San Francisco—each being the narrator’s act of envisioning her “location from a long distance…something that always gave [her] a feeling of vitality.” It is a story which begins in the brightness of day before taking flight and descending into a glowing darkness; an entire life transcribed and bounded by moments of equanimity yet otherwise filled with the drabness of passage and taciturn resilience. The flavor of Tomine’s text gives the distinct feeling of translation which is further advanced by the evident culture of restraint. The lack of overt trickery serves him as well here as it once did in “Hawaiian Getaway.” The convulsions of black humor may be consuming Tomine’s writerly senses at present (at least on the basis of this collection) but it his mastery of discretion which has always served him best.

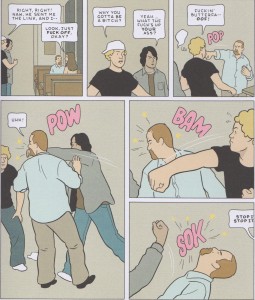

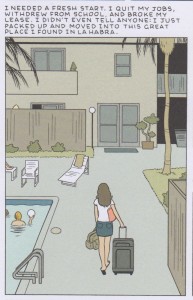

As for the rest of the collection, the less said about “Amber Sweet” and “Go Owls” the better. The former reads like a parody of the genre (see Kim’s review) and the latter is as edifying as watching someone dig the dirt from under his toe nails. It is in “Go Owls” that Tomine manages to mimic most closely the sheer poverty of imagination in so much modern American literary fiction.

It seems abundantly clear why many of these lesser stories exist. If one surveys Tomine’s oeuvre from the 90s to the late 2000s, it is not difficult to see the author settling into a kind of comfortable formula: the cultural arguments which reveal deeper insecurities; the young people mingling and touching in assorted diners, bedrooms, and bars. In terms of number of pages drawn, Tomine’s comic output is minuscule for a career which has spanned two decades. Yet the collective effect of viewing these works as a whole is a kind of worn familiarity. Killing and Dying seems both an acknowledgement of his age and a decisive attempt to get out of this rut even if it is largely a miscarriage.

________

Further reading

(1) A long and detailed interview with Adrian Tomine at Guernica magazine conducted by Grace Bello.

(2) And another interview at Salon with Scott Timberg.