I am a generally happy person. A cockeyed optimist. A Pollyanna. Hell, you know, I’m from the Midwest. I like to like things, and I try very hard to do so. As a self-directed blogger with no editorial mandate to adhere to but my own, I skip merrily through the world of East Asian comics, content to linger over what pleases me. I rhapsodize over the books I enjoy and blow through the rest as quickly as possible—like a panicked sprint through the unexpected cloud of gnats on an otherwise peaceful summer stroll.

For a person like me, “hate” is a fairly nebulous concept, and not all that easily accepted or even understood. For me to hate something—to really loathe a thing—it needs to hit me where it hurts. I can’t vigorously hate a book or a comic or a Broadway musical, say, for simply being incompetent (*cough* Baseball Heaven *cough*). I must be truly, inconsolably offended in order to come even close to real hate.

That said, there are a number of comics I’ve disliked intensely over the years—mainly since I began reviewing things I wouldn’t necessarily choose for myself. Notable objects of my rage have included gender-regressive shoujo manga like Black Bird; creepy, campy BL like Tricky Prince; and the fat-shaming caricature that is Ugly Duckling’s Love Revolution. One of these titles even prompted an experiment to discover how often and how thoroughly I must trash a single series before the publisher would stop sending me new volumes (answer: to infinity). The thing is, when I go back and read my reviews of these books, each of which has incited rage, they seem kind of… weak. Despite my wrath, I could never truly commit to hating these comics, due to their lack of serious intent. Nobody thinks Tricky Prince is Serious Business, including Tricky Prince, and it’s hard to work up genuine, lasting hatred over something that was intended to be disposable from the start.

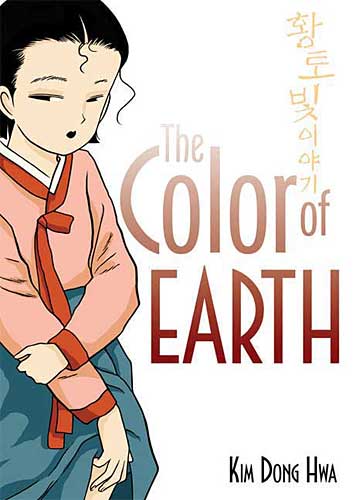

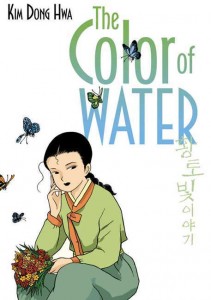

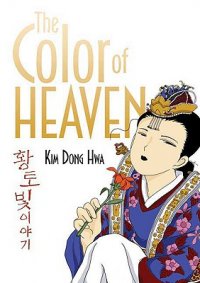

Then came the Color trilogy.

|

|

|

In 2010, I volunteered to host the first manhwa edition of the Manga Moveable Feast. A number of titles were suggested and put to a vote, including some personal favorites, like Byun Byung-Jun’s quirky short comic Run, Bong-Gu, Run!, Uhm JungHyum’s moody romance Forest of Gray City, and JiUn Yun’s sumptuous collection of ghost stories, Time and Again. Unsurprisingly, however, the vote ultimately came down to Kim Dong Hwa’s critically acclaimed manhwa trilogy, The Color of Earth, The Color of Water, and The Color of Heaven, published in English by the lovely folks at First Second. Though I was a big fan of Korean comics in general (and certainly knew of Kim’s series), I hadn’t read read more than a few excerpts myself, so I dug in with verve. And then the hate… oh the hate… it was like nothing I’d experienced as a comics reader before.

The Color trilogy is a coming-of-age story revolving around Ehwa, a young girl in pre-industrial Korea who is being raised by her mother—a widow who runs the local tavern. The story spans Ehwa’s life from the age of seven (when she is first made aware of the existence of penises, thanks to a boys’ pissing contest) through her wedding night (when she gets to know a very special penis on more intimate terms). I choose these parenthetical descriptions purposefully, because that’s what this series is really about: penises and the pursuit of same—that is, when it’s not too busy going on about the lusty beauty of a ripening young woman (yes, these words are chosen purposefully as well).

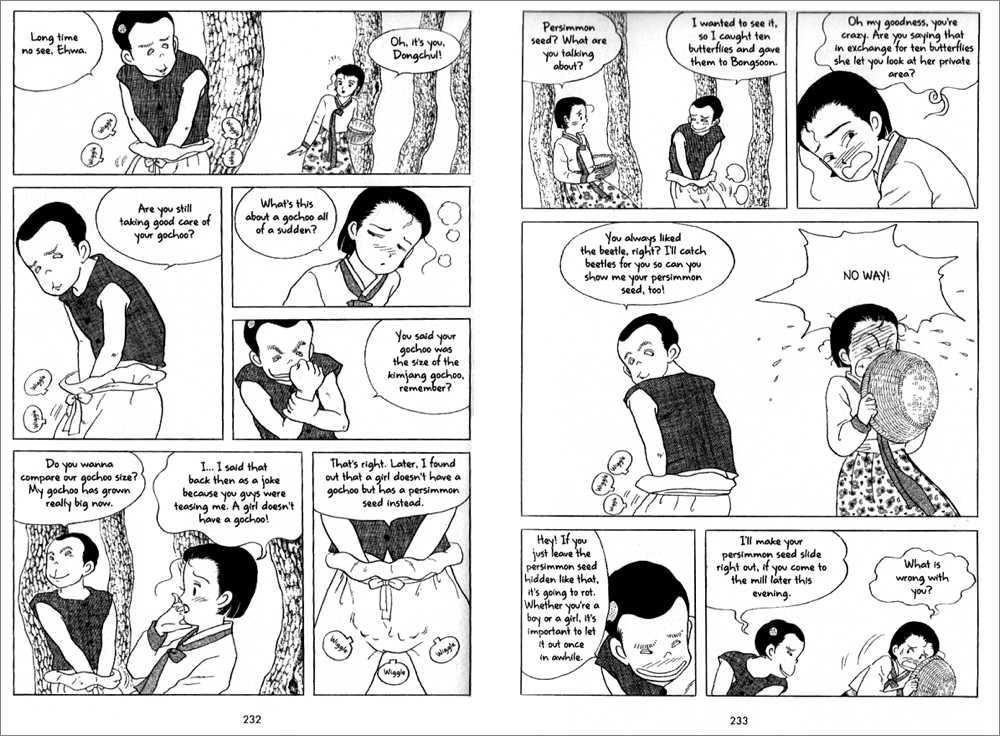

First, the penises. As I mentioned, the story opens with Ehwa, at seven, stumbling upon a pissing match between two local boys. The boys are deeply proud of their own “gachoo” (chili peppers, also a euphemism for “penis”) and they ask Ehwa to show them hers. This sends Ehwa into a tizzy, as she wonders if not having one indicates that she’s deformed. One of these boys is so consumed by his love affair with his own penis that he will later be portrayed as being unable to take his hands off of it.

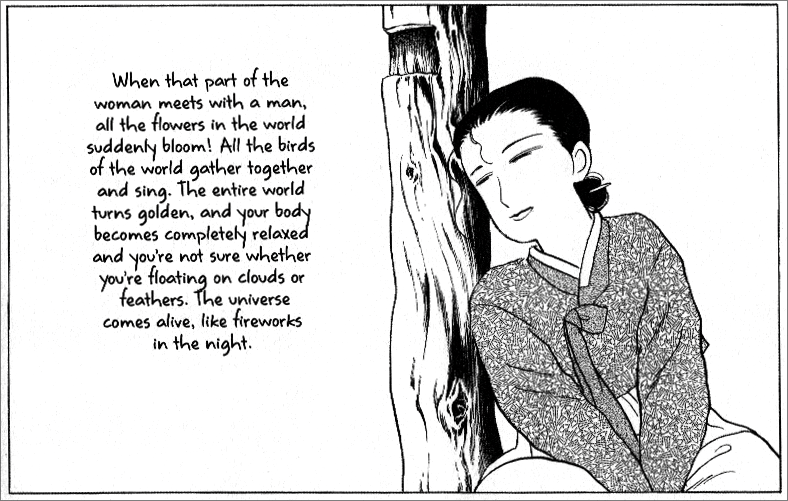

Hey, why should he? It’s a really awesome thing, that gachoo. As Ehwa’s mom explains to her later (after buying a whole lot of ginseng to cook with in order to boost the, uh, energy levels of her traveling suitor known only as “The Picture Man”) when a man’s gachoo comes into contact with a woman’s “persimmon seed” (seriously, this is the kind of language Kim uses throughout the series), something magical happens.

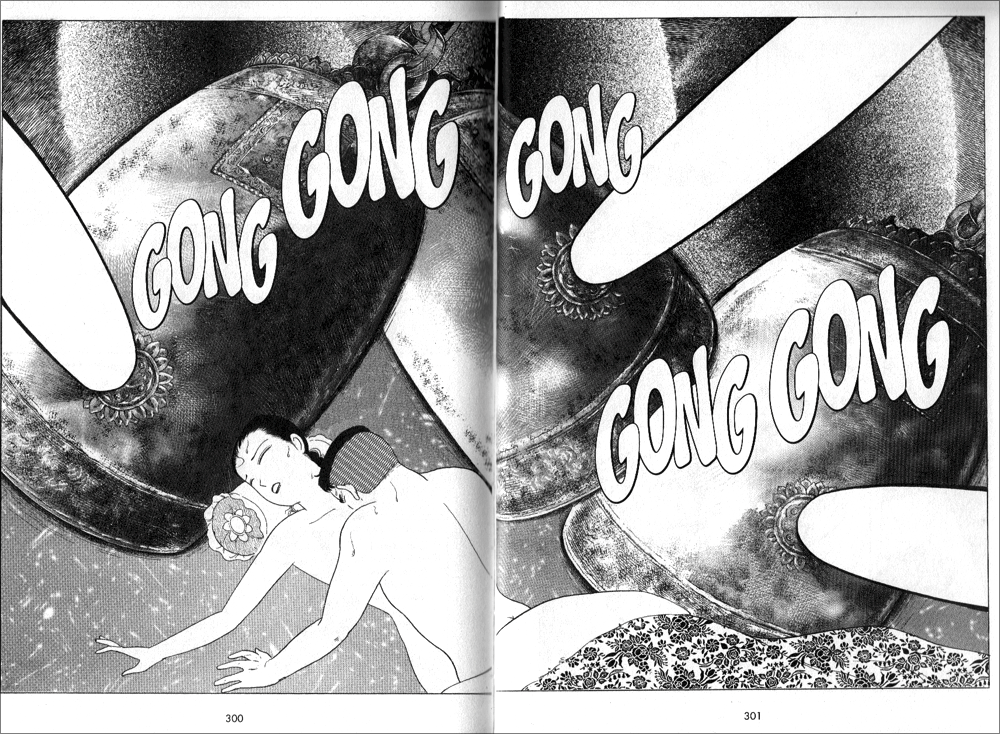

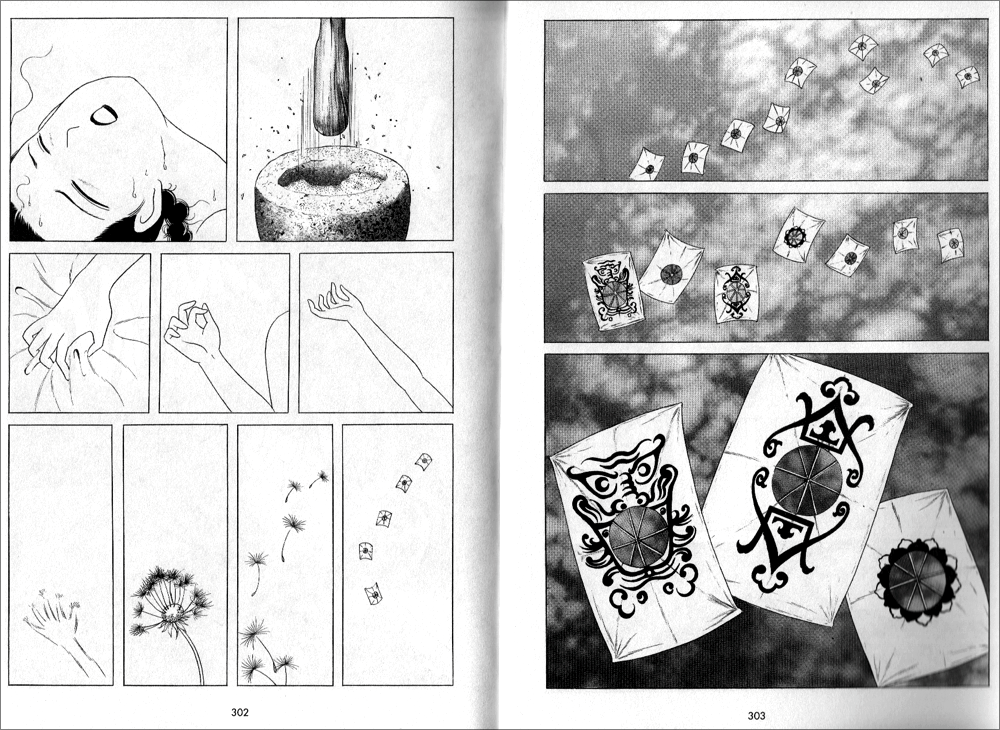

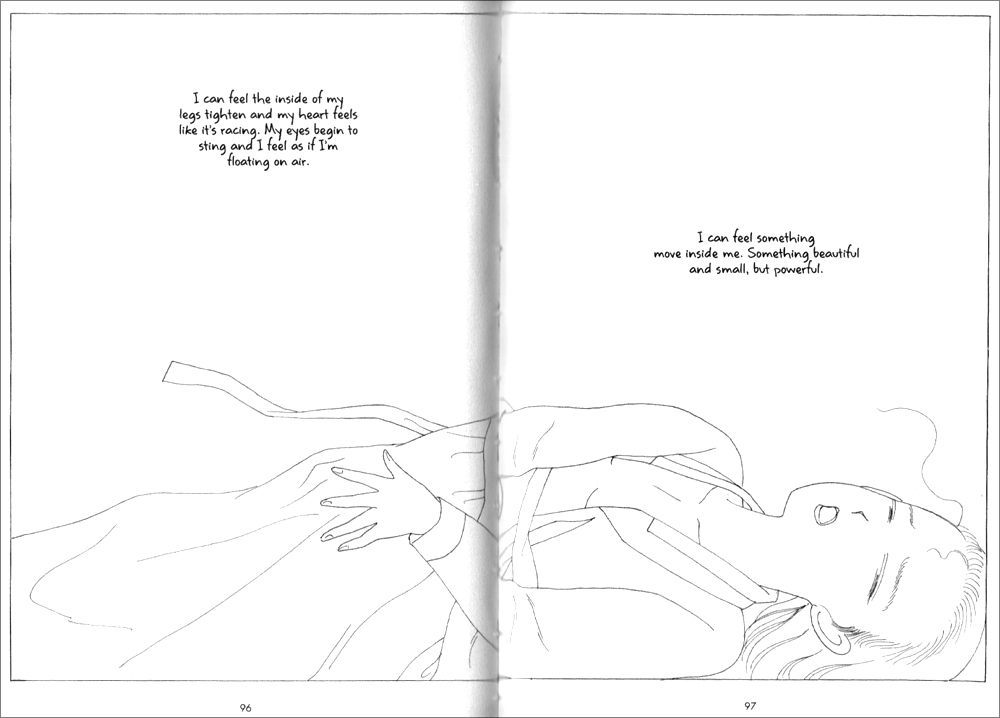

Fortunately, Ehwa gets to experience this magical, floaty, firework-y business for herself at the climax of the book (Get it? “Climax”??), as she’s losing her virginity to her new husband. Though in her case, fireworks and floating on clouds feels more like… a super-phallic bell choir? Mortar and pestle? Um… ?

Though I joke about this being the “climax” of the series, it actually is just a few pages from the end. Ehwa’s journey really does quite literally span the time between discovering penises and getting to be penetrated by one. The entire point of her existence as a character can be summed up this way.

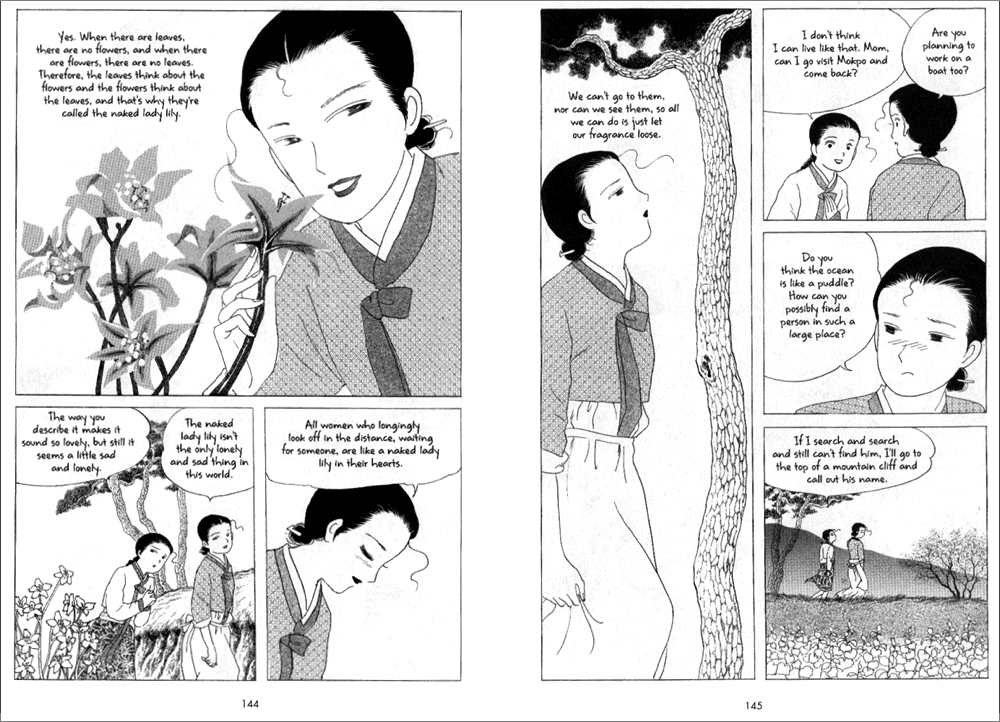

What happens in the middle is largely waiting. Waiting, waiting, waiting. Both Ehwa and her mother fall for wandering men—the kind who spend most of their time traveling for work or simply out of restlessness, but stop in for sex every few months or so. (I once described this type as “… a big, strapping man who values the freedom to wander, is good in a fight, a stallion in the bedroom, and offers questionable financial security. Another male fantasy?”) While this is undoubtedly appropriate to the period and to these women’s circumstances, Kim spends so much time lingering on the wistful beauty of the lonely woman, it begins to feel like a bit of a fetish.

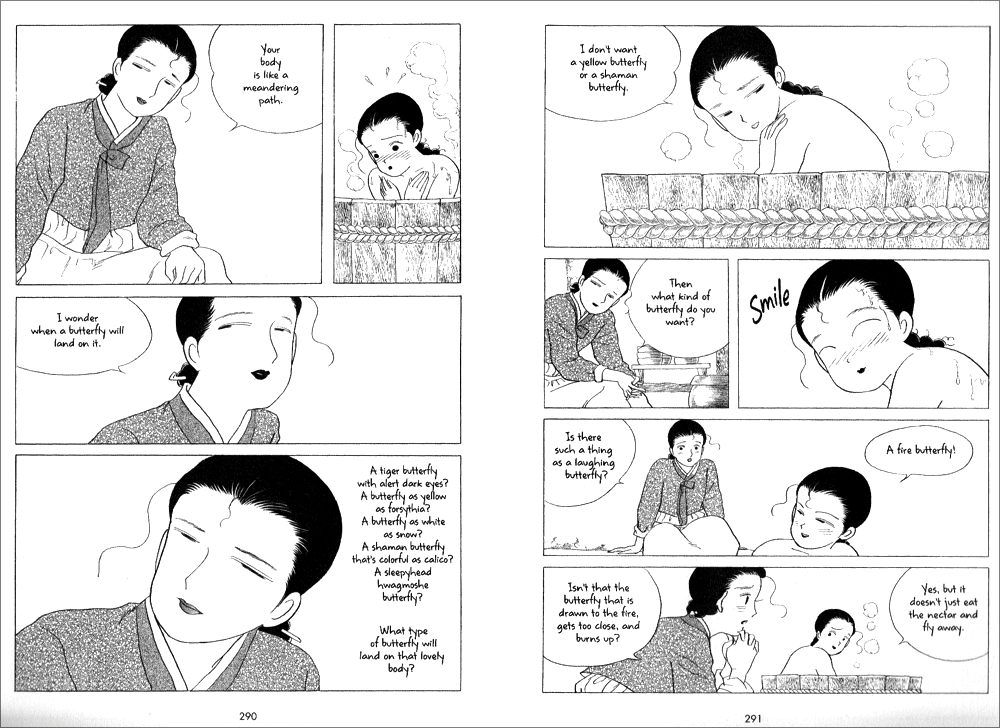

Scenes like this are peppered throughout, along with long-winded discussions in which the lonely, waiting women, the wandering men, and generally everything else of consequence in the story are described as various types of local flora and fauna—to the point that it eventually becomes difficult to remember what or whom all the different flowers, insects, and trees stand for. More than anything else, however, Kim lavishes over the beautiful pain of Ehwa and her mother with genuinely lovely artwork and flowery language worthy of Anne Shirley’s Rollings Reliable Baking Powder story.

But while Kim’s obsession with the feminine loveliness of his characters’ longing reads as simply insulting, his fascination with Ehwa’s burgeoning womanhood borders on downright creepy. Kim is quoted as saying that “the process of a girl becoming a woman is one of the biggest mysteries and wonders of life.” And it’s clear from his portrayal of Ehwa that he considers that process to be entirely sexual. Ehwa has no interests outside of sexual attraction and whatever else is happening with her body—not the tiniest thing. In fact, despite being the only child of a single woman running a tavern all on her own, she doesn’t even seem to have chores to take her mind off her dramatic puberty. Growing up mentally, emotionally, or even just practically seems to be of little consequence to Ehwa or her mother (who remembers just as Ehwa is about to get married that maybe she should teach her how to cook). And while I feel vaguely ashamed for wishing that a female protagonist might take some interest in housekeeping, it at least would give her something to care about besides the long-cherished promise of touching a man’s gachoo.

But while personal interests, hobbies or even standard domestic pursuits appear to be superfluous to “the process of a girl becoming a woman,” the relevant items seem to be:

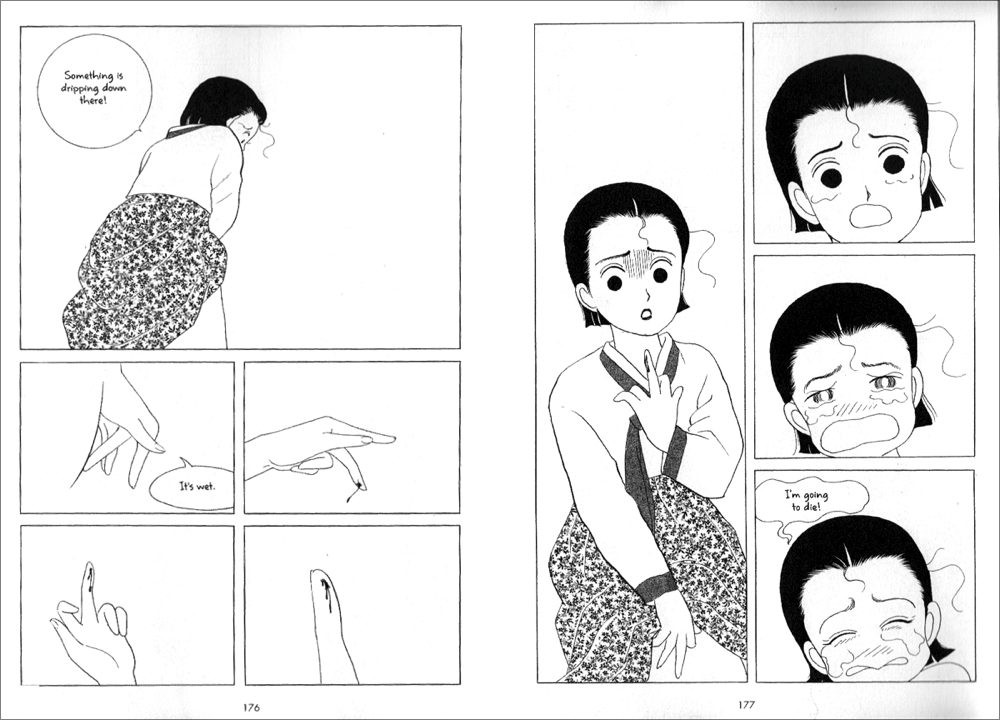

Getting her period.

Learning to masturbate.

And attracting penises butterflies penises.

Yes, Kim Dong Hwa, these truly are the most important aspects of a young girl’s blossoming into womanhood. Thanks for noticing.

Of course, in the end, it’s not Kim’s romanticization of regressive gender roles that really bothers me here, or even his semi-creepy fetishization of womanly “blossoming” (seriously, everything’s got a flower metaphor in this series), not when you get right down to it. I’m a manga fan, after all. I’ve read Black Bird and Hot Gimmick. I survived the first omnibus of Love Hina. I’ve participated in a (not entirely scathing) column on boob manga. What makes me really hate the Color trilogy, is that it’s so widely praised and admired, by male and female readers alike. It is absolutely Serious Business, and that makes it rare fodder for my hatred.

In the books’ endnotes and in Kim’s official bios, he’s referred to repeatedly as a “feminist” writer. He is credited with possessing an “uncanny ability to write from a profoundly feminine perspective.” When, during the Manga Moveable Feast, Michelle Smith and I accused Kim of regarding his female characters’ limited life choices and oppressive environment with “loving nostalgia,” we were criticized in turn for expecting more progressive sexual politics from a period piece. The Color of Earth was published in 2003, yet even Tezuka never treated his (highly questionable) female characters with this kind of rosy condescension.

I tried very hard to like the Color trilogy, but even my most sincere, Pollyanna efforts failed me on this point. In the end, it may be one of the very few comics this midwestern optimist could ever truly hate.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.