The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

______________________

In 1958, an estranged Hungarian Jew and Holocaust survivor named Flóra “Florence” Klein brought her eight-year-old son, Chaim Witz, to New York City from Israel to seek out a new and better life. Chaim Witz’s name was soon Americanized to Gene Klein, and would eventually become the infinitely more famous double-alter ego Gene Simmons.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

After a year in an Orthodox Jewish school, the young Klein made his transition to America complete by entering the New York City public school system. Unable to speak or write English at first, Klein quickly turned to the new and fascinating world of American popular culture to learn his adopted language. While other kids were outside playing baseball or kick-the-can, Klein immersed himself in almost all of the mass entertainment arts: movies, television, science fiction, cartoons, pulps, and especially comic books. Reflecting later about those early years, he said once he saw Superman and Batman, “he was hooked.”

Then, in 1964, at the age of 14, he saw The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, and a new world opened up for him: pop music. As he said decades later in his book Kiss and Make-Up, “My first thoughts about pop music were born that night, and they were simple thoughts: If I go and start a band, maybe the girls will scream for me.”

Klein’s first band was Lynx, announced incorrectly as The Missing Links – the name which ended up sticking – and it consisted of Klein, Danny Haber and Seth Dogramajian. Like Klein, both band-mates were obsessed with comic books. Klein elaborated about their four-color passion: “Seth and I used to publish amateur fanzines about comic books and science fiction. We would write articles, review movies, and talk about characters from television shows. His fanzine was called Exile; mine was called Cosmos. But after the Beatles, it became clear to us that, as much as we loved science fiction, it wasn’t going to get us where we wanted to go with the girls.”

But even as Klein began actively forging ahead on his nascent music career, his entrance into the world of science fiction, comic book, and film fandom exploded.

To say that Klein was an active fan of the popular arts would be a gross understatement. He not only read and collected comic books, monster magazines, film magazines, pulps and related science fiction and fantasy books; he also published his own fanzines and contributed material to scores – perhaps even hundreds – of other fan publications.

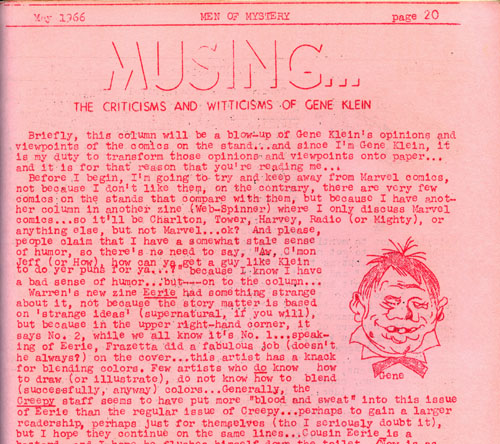

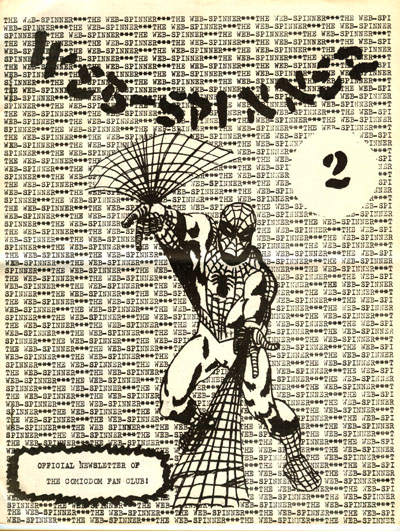

From 1965 to 1970 – through the remainder of high school and beyond – Klein’s fanzine-related output was prodigious. Here’s just a partial list of fanzines with which he had involvement: Adventure, Arioch, Asmodeus, Asterisk, Beabohema, Bombshell, Chamber of Horrors, Cooper’s Hero Hobby, Cosign, Cosmos, Cosmostiletto, Crabapple Gazette, Critique, Double: Bill, Dynatron, Ecco, Exile, Famous Fiends of Filmdom, Fantasy Crossroads, Fantasy Film Journal, Fantasy News, Faun, Giallar, Gore Creatures, Harpies, Id, Iscariot, Mantis, Martian Journal (MJ), Men of Mystery, Monstrosities, One Step Beyond, Orpheus, OSFan, Osfic, Proper Boskonian, Pulp Era, Quark, Ragnarok, Ray Gun, Sanctum, Satyr, Sci-Fi Showcase, Screen Monsters, Sirruish, Solarite, Space and Time, Spectre, Splash Page, Starling, Super Spy, Terror, Tinderbox, Trumpet, Web Spinner, Weirdom, and Wonderment.

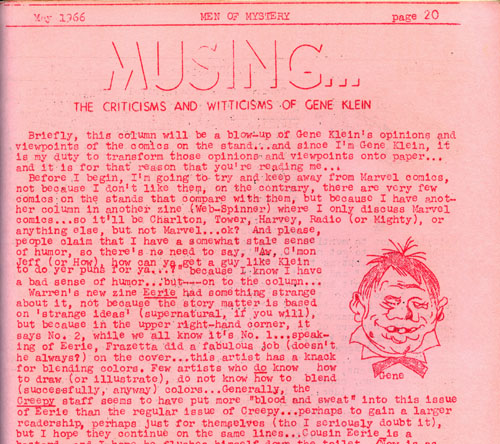

Klein’s contributions were as varied as his popular culture interests. He drew artwork; wrote opinion columns; reviewed films, TV shows, comic books, pulps, books, fanzines and newspaper comic strips; and wrote countless letters of comment.

His signature writing style could be summed up in one word: blunt. Klein rarely pulled his punches. If he thought a fan publication had bad art or a poorly written article, he would not hesitate to say so. Despite this, many editors apparently didn’t mind the abuse, because his letters kept on getting published. So did his sometimes acerbic articles.

For example, in the fanzine Web Spinner #2, published in August 1965, Klein summarily raked Marvel editor Stan “The Man” Lee over the coals in an essay titled “The M.M.M.S.? You Can Keep It!” Klein felt that the $1 membership fee Lee was charging for the new club was exorbitant for what members received in return: a record, a certificate, some Thing stickers, and a coming events news sheet. Klein then went on to discuss some of Marvel’s other merchandising products being concurrently advertised, such as $1 Marvel stationery pads and $1.50 t-shirts. And while he admitted they were nice to look at, he complained, “who has so many dollars to contribute to Lee’s ever-growing pockets?”

However, just about 10 years later, there would be some industrial-strength irony in those words when Klein, as Gene Simmons, would help mastermind a long-running and innovative KISS merchandising machine that would eventually generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue – a marketing juggernaut that made Lee’s modest mid-1960s operation look positively quaint by comparison.

Klein’s soon-to-be-considerable entrepreneurial skills started in those halcyon fan days when he started buying and selling comics to finance his hobbies and fledgling music career. He utilized the same mimeograph he used to publish his fanzines to print up flyers and other ads offering to buy old comics for a dollar a pound. He’d then sift through the stacks of purchased comics, re-selling the most collectible ones to other fans at a tremendous mark-up.

As the 1960s came to a close, Klein went off to college and his music career began growing. Something had to give, so Klein’s fan activities began tapering off. But even as late as 1969, Klein and his band-mates were still doing a significant amount of work for fanzines. For example, in the fifth issue of Gordon Linzner’s science fiction fanzine Space and Time, published in the spring of 1969, three of the four contributors providing artwork for the issue were current or former members of a Klein band: Klein, Dogramajian and Steve Coronel.

But, the die was cast, and Klein’s music career soon displaced most of his former fannish activities. In the Dec. 14, 2005 edition of the fanzine Vegas Fandom Weekly, science fiction fan and editor Arnie Katz looked back on Klein’s departure from fandom, circa 1969. “He was originally in horror/SF movie fandom and was only beginning to understand the “faster track” of SF fanzine fandom when his life got very busy,” Katz said. “Bill Kunkel and I (who barely knew each other at the time) both corresponded with Gene and, I think, saw him as a promising young fan. He came along at about the same time, and from the same “other fandom” source, as John D. Berry. John grew into a very fine fan while Gene’s fan career ended due to his musical success.”

Today, several different fandoms claim Klein as one of their own, and they are all technically correct. Klein was, in fan parlance, a “cross-over fan” – i.e., he had a foot in multiple fandoms. But back in those pre-Internet days, unless a fan made his multiple allegiances a point of contention in his letters and essays, few of his peers would have even been aware of them.

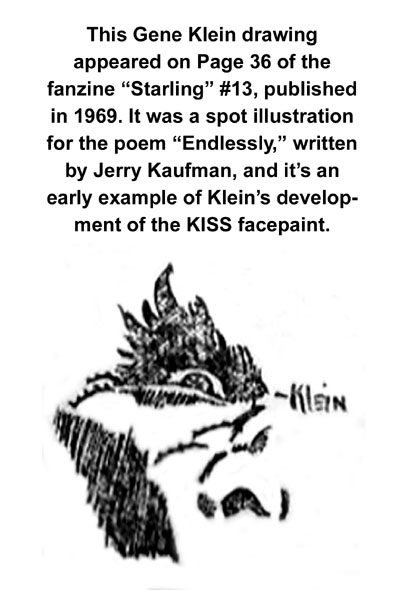

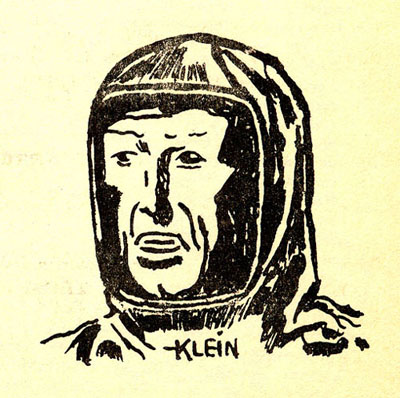

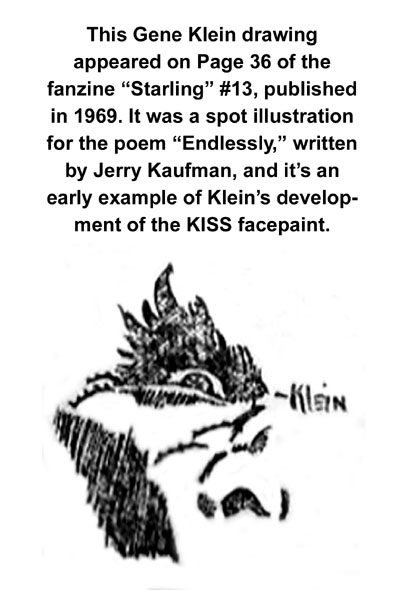

There were no overt indications during this period that anything like KISS was in Klein’s future. He and his band-mates rotated in and out of various band iterations as they struggled to find the right mix of musicians and the right sound. However, there is a tantalizing clue in the form of an obscure 1969 fanzine drawing by Klein that could indicate he was dreaming of something bigger four years before KISS was born. The drawing was published on Page 36 of the fanzine Starling #13 as a spot illustration, and it depicts what appears to be a prototype design for the eye makeup Klein (as Simmons) would later wear as his KISS character, The Demon.

In 1970, Klein and band-mate Stanley Eisen formed the band Wicked Lester, which was the precursor to KISS. After two years of struggling unsuccessfully to build the type of band they envisioned, and despite a recording contract with Epic Records, for various reasons the two felt shackled by the arrangement and walked away. This gave them the freedom they needed to start fresh and build a new band from the ground up.

They moved to New York City, found a drummer named Peter Criss (Criscuola), and a lead guitarist named Ace (Paul) Frehley. Around the same time, Gene Klein changed his name to Gene Simmons, Stanley Eisen changed his name to Paul Stanley, and the early versions of their trademark makeup and costumes began to take shape. Stanley coined the name KISS, and although they probably had no inkling of it at the time, the band was ready to make history.

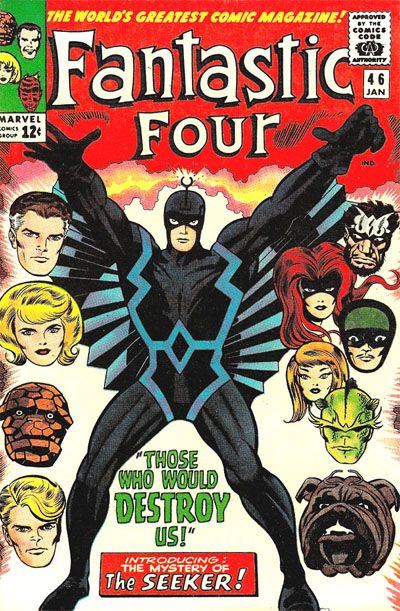

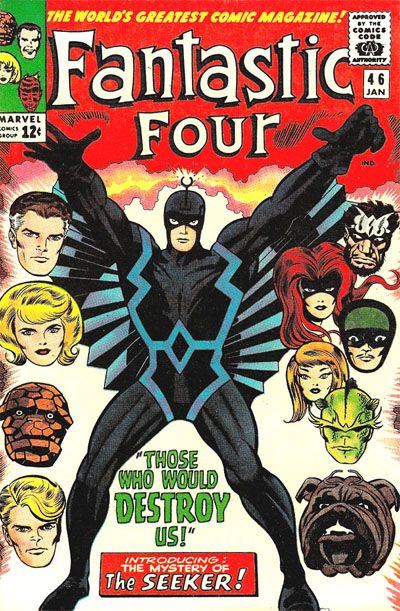

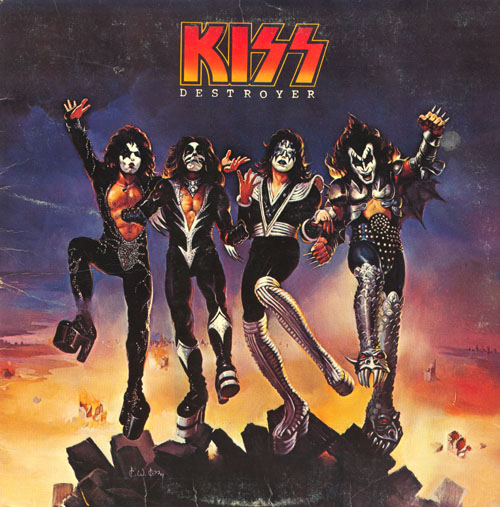

Simmons recalled in KISS and Make-Up how his Demon character persona originally developed. “Later on in our career, when we went to Japan, the reporters there wondered if our makeup was indebted to the Japanese kabuki style. Actually mine was taken from the Bat Wings of Black Bolt, a character in the Marvel comics The Inhumans. The boots were vaguely Japanese, though – taken from Gorgo or Godzilla – and the rest of the getup was borrowed from Batman and Phantom of the Opera, from all the comic books and science fiction and fantasy that I had read and loved since I was a child.”

Simmons also attributed his trademark Demon hand gesture, consisting of the index finger and pinky finger extended, to comic book artist Steve Ditko’s two trademark characters: Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. The former would position his hand that way to shoot webbing from his web-shooter, and the latter would use a similar gesture to conjure up magical spells.

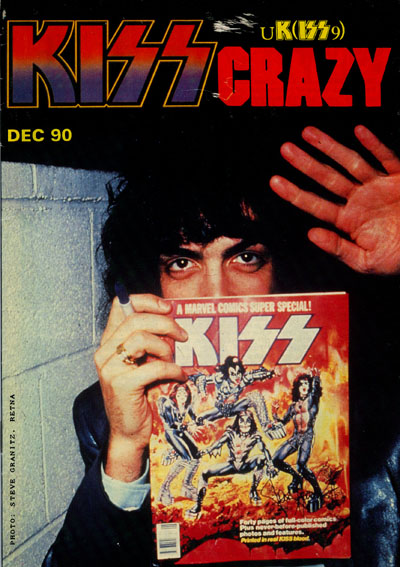

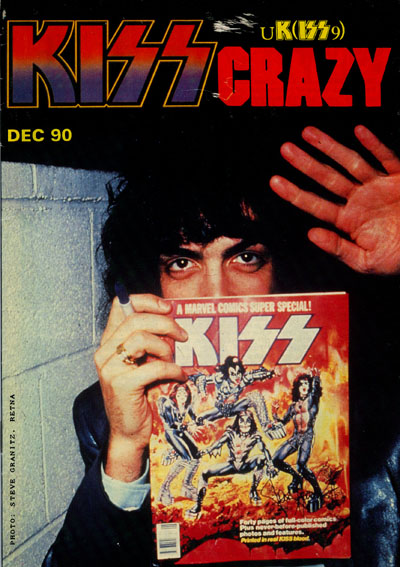

In many ways, Simmons was channeling his inner superhero when he designed his on-stage persona. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Jack Kirby’s comic book character named the Demon debuted on newsstands just six months before the birth of KISS. As Simmons points out, his own character was an amalgam of many comic book and popular culture influences. Likewise, adopting stage names at the very moment their KISS characters were born was another nod to the superhero’s penchant for having an alter ego. Later, Simmons would even take hiding his alter ego to the next level by covering up the bottom of his face whenever his make-up was off and cameras were around. (KISS bandmate Paul Stanley demonstrates the technique in the picture below.)

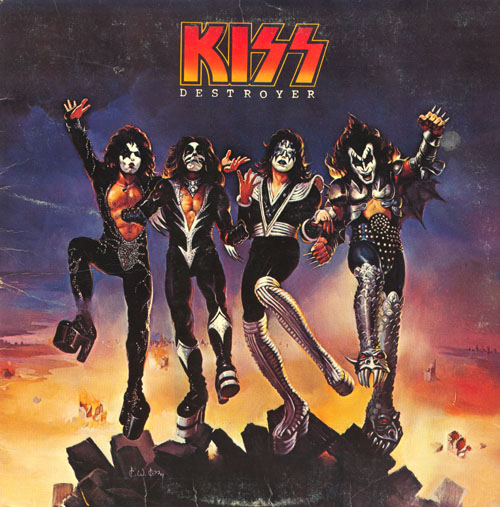

The band’s first performance took place at the Popcorn Club, in the New York City borough of Queens, on January 30, 1973. There were three people in the audience, and KISS performed sans make-up. By March, however, the band had started developing its iconic look and four signature characters: The Demon, Starchild, Catman and Spaceman.

According to the 2012 (revised) edition of The Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal, although KISS eventually became one of the most popular bands of the 1970s, they struggled initially to get noticed. KISS released three albums prior to Alive! but the sales were weak. At the same time, their live concert performances were regularly selling out. So the decision was made to release a double album made up entirely of live KISS concert performances. Live albums were still unusual during that era, so it was a bold move – and a highly successful one. Alive! apparently captured the energy and spectacle of KISS’ concerts, making the band members superstars overnight.

KISS had a huge influence on almost every heavy metal band that followed – whether the later bands realized it or not. This “ghost” influence is similar to the influence comic book artist Jack “King” Kirby had on his peers and subsequent generations of comic book artists.

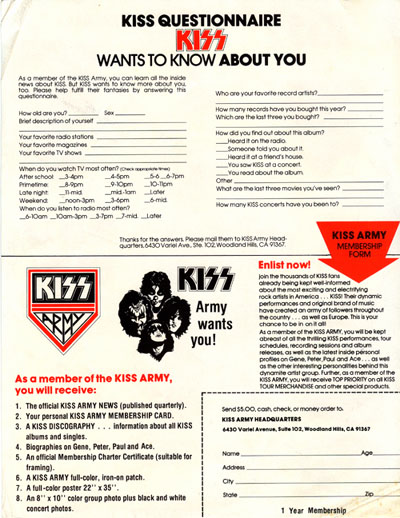

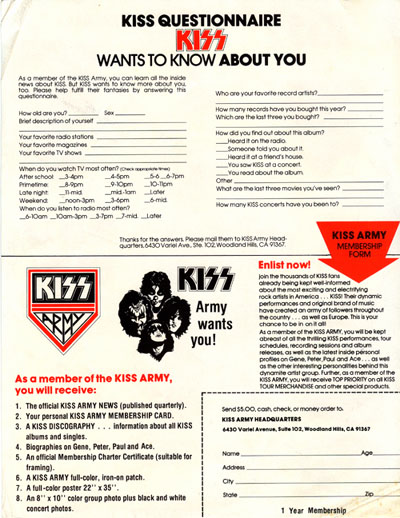

As mentioned earlier, KISS was the first rock band to extensively market and brand itself through merchandising. In the mid-1970s, KISS albums came with an order form insert offering membership into “The KISS Army” for $5, and a host of other KISS merchandise for sale. Suddenly, according to The Encyclopedia of Heavy Metal, KISS products were everywhere. “This may not seem like a big deal today, but at the time it was highly unusual for a band to market itself this aggressively as a commodity.”

To his credit, even as KISS was rocketing to fame, Simmons never forgot his fannish roots, and still kept in touch with some of his long-time fanzine buddies. For example, in 1976, after the KISS World Tour, Simmons wrote a letter of comment that was published in issue #25 of Gore Creatures, a fanzine he had submitted contributions to during the late 1960s while he was still in high school.

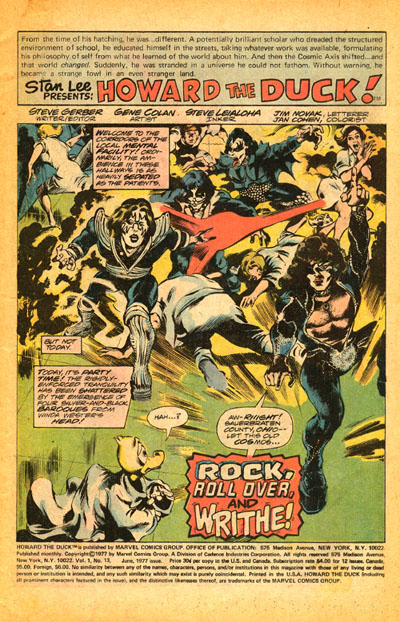

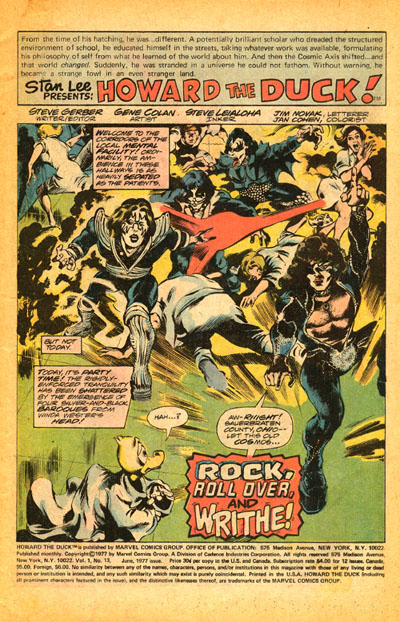

The band’s popularity soon opened doors with the very comic book industry Simmons and his early band-mates had adored. “From the beginning I had been heavily indebted to comic books, and in 1978 (sic) we made good on that relationship by getting a comic book of our own,” Simmons said. “First a Marvel artist (sic) named Steve Gerber who was a big fan put us in the last two issues of Howard the Duck. We were demons who possessed Howard. Marvel noticed that those two Howard the Duck issues soared in sales even though we weren’t on the cover. So they approached us about a KISS comic book.”

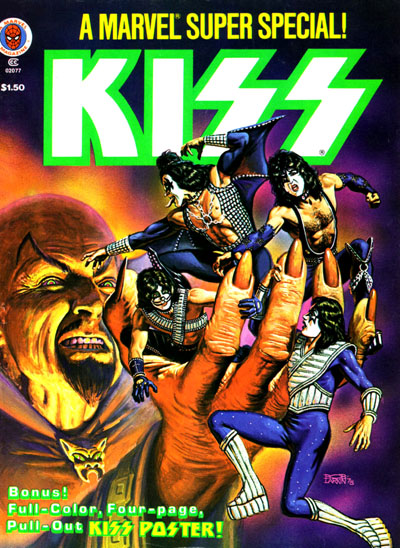

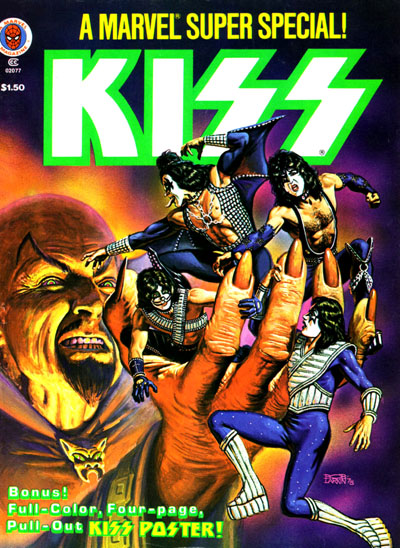

The very first KISS comic book Marvel published was Marvel Comics Super Special #1, a magazine-sized comic published in September 1977. The rollout of the magazine received national coverage because of a brilliant marketing idea: At Marvel’s printing plant in Buffalo, N.Y., KISS, in full make-up and costume, and in front of the cameras and a notary republic (and Stan Lee, of course), had blood drawn from each band member, after which it was mixed in with the printers ink used for the magazine’s print run. According to Simmons, the issue “became Marvel’s biggest-selling comic book.”

A follow-up magazine-sized comic, Marvel Comics Super Special #5, was published a year later in Dec. 1978. Marvel also published the trade paperback KISS Klassics in 1995, and KISSnation Magazine in 1996.

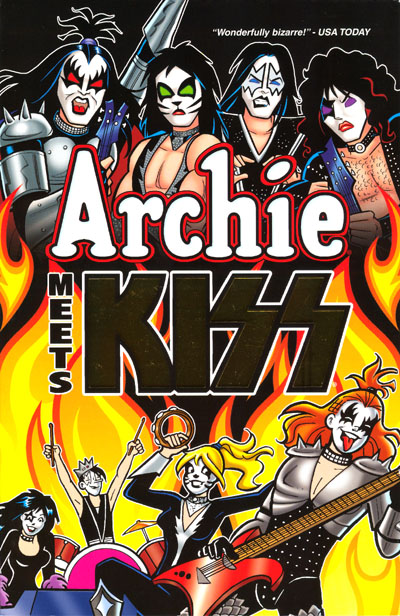

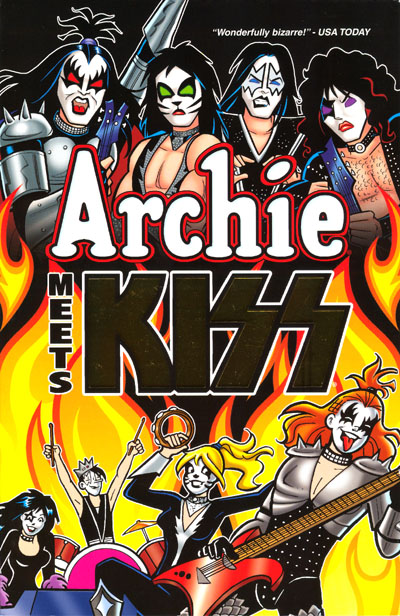

Since then, KISS has had many other licensed comic books published by a variety of comic book companies. For example, Image published 31 issues of Todd McFarlane’s KISS: Psycho Circus from 1997-2000, followed by four trade paperbacks and five spin-off magazines. Dark Horse was next, publishing a 13-issue series KISS in 2002. Platinum Studios published KISS 4K in 2007, and even Archie Comics got in the act in 2011 when it published, Archie Meets KISS. Most recently, IDW has had a licensing agreement to publish KISS comics, releasing KISS, KISS Greatest Hits, KISS Kompendium, and KISS. And the KISS comic book ties keep on coming…

Like millions of immigrants before him, Simmons came to the United States with nothing but a dream. And whether one likes the music of KISS or not, no one can deny that Simmons took some of his wildest fantasies and turned them into reality – and built a world-wide army of ardent fans in the process.