Sammy Harkham’s Crickets #3 rivals in substance and importance two other comics that were published in a similar format: David Mazzucchelli’s Rubber Blanket #3 and Daniel Clowes’ Eightball #23. Harkham seems to be best known for editing the chameleonic, graphically revolutionary anthology Kramer’s Ergot and he has served his artistic community well with those efforts. However, Harkham’s own work is among the best in KE.

His Lubavitch, Ukraine, 1876 in the sixth issue depicts the artist’s namesake living in an orthodox community way back in the day in an intimate and momentarily heart-stopping tale. Harkham conveys a delicacy of gesture rarely seen in a medium that has been dedicated largely to overstatement and explosive violence. That is not to say he is entirely adverse to spectacle, his sprawling post-apocalyptic cover for the impressively oversized Kramer’s Ergot #7 is gorgeous, but his single page broadsheet strip in that issue has a touch of Hergé and Frank King and reads like a pivotal moment near the end of a very sweet unmade Coen bros. film.

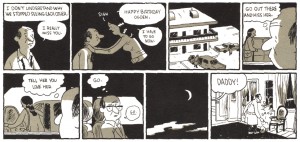

The latest issue of Harkham’s solo comic Crickets is subtitled “Sex Morons” and this is an apt description of the characters in the two major stories inside. The first is a reprint of The New Yorker Story, which probably should have appeared in The New Yorker itself, but instead ran in Vice, the iconoclastic and often disturbing free magazine of fashion, politics and youth culture. In four dense pages, Harkham shows the final crisis in the midlife of a writer and Yale professor as he cheats on his wife, fails to care for his daughter and betrays his colleague. A lot of information is packed into a short piece which seems oddly realistic, given how cartoony the drawings are.

Harkham’s earlier fantasies and vignettes seem more freeform or improvisational, with hermetic, interiorized visuals. By that I mean non-referenced, non-observational drawings with some apparent influence from artists such as E.C. Seger and other early daily/Sunday comic strip artists, along with hints of Moebius, Chester Brown and Al Columbia. By contrast, the narratives in Crickets #3 are informed by research into the particular times and places shown. The stories veer towards a form of naturalism, perhaps closer in spirit to the more serious and/or historical comics narratives long produced in Europe by artists such as Jacques Tardi and Vittorio Giardino.

The condensed but ultracoherent narrative style of The New Yorker Story carries through into the main story, Blood of a Virgin. Harkham has a talent for dialogue and he draws believable continuity and nuanced expressions. His storytelling is clear and his page designs, panel framings and lettering incorporations are elegantly composed. His hand is light and his line is still cartoony in that it increasingly evokes the direct but fragile emotionality of Charles Schulz, but now it also recalls the vigorous simplicity of Roy Crane’s Wash Tubbs.

I wrote to Harkham with some questions about the work in Crickets #3. “There is an emotional clarity you can get across with characters in comics that can be a hinderance or a real asset depending on what you are doing/aiming for,” he told me. “Cartooning is knowing how to use the sickeningly stupid blunt emotion of each panel and build something emotionally complex of it. This really came together for me working on The New Yorker Story. The panels were so small, the most important thing was that they were easy to read. So that meant I didn’t have room to make beautiful drawings or to be vague about what was happening in a given panel.” Still, for all their functionality the drawings are beautiful, particularly when the visual parameters that they describe are qualified and given body by the color overlay. Harkham often uses a single additional color in his work. Here, the pale olive layer affords the spare drawings considerable weight, space and light.

Harkham says, “I don’t really strive for realism, but more for specificity.” To that end, he researched the trappings and landscape of the period shown in Blood of a Virgin. He says, “I wanted to do a story about Los Angeles. Much of the inspiration to work on it is driving around the city and day dreaming, looking at old college yearbooks and photos and getting excited to draw a weird pair of woman’s shorts or a haircut or living room.” As someone who came of age in the 1970s and realizing Harkham wasn’t born until the next decade, I’d have to say his story is as close as I’d like to come to reliving those years. Somehow, he perfectly captures the bleak feel of 1972, as the ideals of the 1960s coagulated into opportunism and excess.

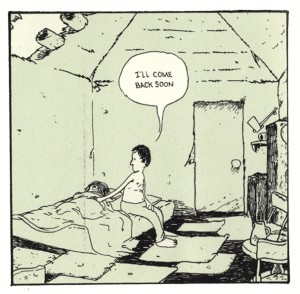

Harkham’s protagonist Seymour fights for a chance to write and direct his first feature film while working a day job editing trailers for Val Reed, a producer of exploitation films. He holds his temper as his boss insists on buying his “werewolf script” cheap. Seymour is given to understand that whatever film emerges from the process will bear little resemblance to what he wrote, and that the job of directing the project will most likely be given to another man. He must eat these indignities, because he needs his mentor’s help and connections.

The story is told in a cinematic style, in other words the sequencing and viewing angles chosen by the artist simulate the vantages of a camera moving around the characters and environment. It also deals with cinema. Harkham imbeds the story with specifics of the then-contemporaneous LA and the horror movie culture and filmmaking process of the time. There are several explicitly instructional micropanel passages in Blood of a Virgin, including one that depicts Seymour editing film at his job.

“I worked on those manual editing bays at CalArts,” says Harkham. “I went back to refresh my memory when drawing the comic.” I showed Harkham’s editing sequences to my friend, animator and commercial director M. Henry Jones, who said, “That’s a Steenbeck, no, wait…hmmm, maybe it’s a KEM….okay, he’s got that right, but he’s using a flat plate….actually, I think it’s a Moviola. Wow, look, he drew the trim bin. And the bit about trying to use the phone with strips of film hanging around your neck…nice. When I’d hit the floor, I’d just stay there.” As usual, it is a little hard to nail Henry down, but he attests to the basic accuracy of the process that Harkham drew.

“I also spoke with Joe Dante about what the daily life of being an editor back then was like. Very similar to being a cartoonist—solitary hours, bad backs,” Harkham says. He characterizes Dante, director of The Howling, Gremlins and Small Soldiers, as one of “that first wave of ‘monster kids’ who grew up watching Universal horror movies on tv, reading Famous Monsters of Filmland, the generation of guys who wanted to work in horror and sci-fi and didn’t look at it like a stepping stone to legitimate cinema, but a place to BE. Kind of like comics.” As with Seymour, Dante was initially a writer for horror zines like FMoF and Castle of Frankenstein. He began his film career working for exploitation movie mogul Roger Corman in the period Harkham depicts, in a similar capacity to that endured by Seymour. Dante’s early film Hollywood Boulevard was created when Corman bet another producer that he could make a film in a week. Like the project Seymour is unwillingly used for, the movie was assembled using extra footage from other productions. But under examination, there is more to “Blood” than these correspondences.

The story explores themes also seen in Harkham’s earlier work Poor Sailor, wherein a young husband realizes his dreams of adventure at the expense of his arm and the lives of his brother and his wife. In Blood, Harkham depicts experiences which might be considered common to young couples who are trying to get ahead in their careers while (supposedly) sharing the responsibilities of small children. He shows both vantage points on the marriage and motivates both partners’ actions. Seymour’s passage through the story is deliberately timed. He keeps a tight schedule for work, always having to considering the delays of LA traffic, but is often late when it comes to his family. At one point, he promises to be home at a certain time and is on his way out the door from work, but then stops to watch some “sadist” footage with a co-worker. Forty-five minutes later, he’s late and has brought the wrong thing home.

Seymour makes dinner for his wife and himself, but she must eat hers alone because he “has to” take what is ostensibly a business call. Much later, his plate is cold and he’s still on the phone, now simply blabbing about film trivia. Then he is frustrated that his wife does not respond to his advances and that she cannot listen as he reasons a way to tolerate working on his now-adulterated dream project, because she is exhausted from taking care of the baby on her own. Seymour shares some of the childrearing, but his resentment and impatience are obvious when he tries to skip his “turn” and grabs the baby’s leg too tight while changing a diaper.

Seymour keeps his overtired wife awake by watching a version of the then-common pathetically absurd late night horror film hosts on TV until he finally falls asleep. In a moody two-page passage, Harkham renders the tonal-scale test pattern that used to come up after a TV station signed off for the night with a set of square panels of Seymour loudly snoring. His wife finally kicks him out of the room with a dictate to take the garbage out. Seymour sleepwalks outside into the misty wee hours, a scene reminiscent of the fog-enshrouded sets of classic horror films, as well as of the hypnotic dreamscape meditations of Harkham’s friend and contemporary Kevin Huizenga.

Harkham often deals with brittle relations between men and women. In Blood of a Virgin odd things are done to women, often involved with covering their heads and faces. Seymour meets Joy at the house of some “effects guys” who are making a cast from her head. The careless FX artists hurt her by forgetting to apply vasaline to her eyelashes and brows at the beginning of the casting process.* Joy and Seymour worked together on productions in the past and a closer link is implied. She had apparently attempted suicide since he’d last seen her, she has healed cuts on her arm. Was it connected to something he had done?

The costuming of the characters for the Hollywood Halloween party that is the centerpiece of the story is telling. Joy dresses as death, Seymour’s “costume” consists only of a scar on his cheek, his unnamed wife dresses as a clown. Her presence at the party is specifically requested by his boss, but she is unable to attend because the babysitter doesn’t show up. She resignedly removes the clown suit and makup as Seymour leaves alone, and the relief he feels is the first of a series of overt infidelities.

This three-panel sequence is indicative of the layers of irony that Harkham imbeds in his orchestrations of word and image. The dense overlapping lettering of the first two panels does not close down their general feeling of openness of composition, it represents the apparently chaotic but interconnecting sounds of a family. In the third panel, despite what Seymour is saying as he slithers out, the perspective of the background contracts, encasing him, doors are closed, his arm is behind him in submission to an accusatory click.

At the party, Seymour proceeds to get wasted and becomes involved in a coked-up, sexually violent subparty. The worst of it happens across from a gentle page containing twenty-four square panels that show Seymour’s spouse changing diapers, putting the baby to sleep, making cookies, being made to feel old by a group of trick-or-treaters, smoking a cigarette and being ignored by their neighbor—the contrast of maybe-death and life, of the perverse and the mundane is powerful.

Back at the party and furthering the overarching motif, Seymour “accidentally” elbows Joy in the face when she surprises him while wearing her skeleton mask….there’s much more, but I do not want to continue except to note that Seymour justifies his behavior over the night to himself as a reaction to the oppression of time.

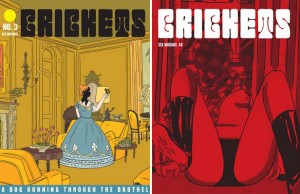

For all of Harkham’s more accessable qualities, such as clarity, accuracy, and his thoughtful handling of human relationships, his work has a transgressive edge that becomes sharper when one considers his comic as an object. The images on the exterior covers are unsavory. They are printed in black underlaid with a reddish purple that amplifies an aura of extreme sleaze…but why does it present so? On the front cover, the white logo is done in a generic psychedelic style of the late 1960s, early 1970s. A woman is drawn with slashing ink brushwork and wash, close to the picture plane reclining against a window, in black panties and vinyl boots, her legs spread and a breast exposed, her head and other breast covered with a checkered cloth. The cover color can then be seen as that of blood or otherwise a color of bodily interiority and in such proximity to female genitalia, evokes the “blood of a virgin” or perhaps menstrual blood. On the back cover, the drawing is done in a cheesey cartoon style like the gags in old men’s magazines. In the foreground, a man in a bonnet or nun’s habit sweats as he ogles the buttocks of a woman in dancer’s tights bending over before him, in apparently refined setting. The subtitle runs in white letters along the bottom, in Italian.

Hidden on the inside front and back covers are two elaborate line drawings printed with full color separations, which have the aspect of illustrations in The New Yorker. The subjects are carefully posed and give the impression of absolute stillness. On the inside front cover, a woman in Victorian dress stands in an elegantly furnished, high-ceilinged room. Her face is covered with a black dripping substance (ink? tar?), reemphasizing the motif of women with obscured faces. She holds a butterfly and the angle of her raised arm echoes that of the pallid, phallic candles leaning from a wall fixture. The inside back cover shows a room with modern furniture and a Van Gogh painting on the wall. A green, cut-off male head is laying on the floor, dripping green gore. A red woman lays on her back on the floor, her legs on a coffee table, her head under the skirt of an easy chair, her arm raised as she makes the peace or V for victory sign.

The images on the covers relate to the stories, if obliquely. Perhaps the head on the floor on the inside back cover is the same as that on the table of the feeble late light TV horror hosts. In three of the four covers, women’s heads are obscured. The scene on the front cover reflects a sequence in the main story, but with some discrepancies. The checkered cloth over her head is different than that seen in the story. In our contemporary context, a covered female head brings to mind the practices of the Taliban and the checkered fabric also reminds one alternatively of Arab headgear and an all-American picnic lunch. Her position and the color might also suggest a return to the womb. The design and images presented to the reader make the package look like a particularly cheap and degraded vintage fetish mag, in seeming denial of the sophistication of the sensitive cartooning bound within.

If the covers were stapled inside out, it might be a more commercial product…or not. One wonders, in a time so challenging to print media, what sells more magazines, refined drawings or pornography? Some online vendors are using Harkham’s original cover concept to represent the issue. Harkham’s decision to use the crimson cover was probably only possible because the book is self-published. It affects the possibilities for store display, the impact on the potential customer and the overall reading of the work.

The intended audience comes into question. Truthfully, your standard superhero comic cover is often no less psychosexual, but the cover for Crickets #3 is encoded with some powerful porn signifiers. Is the comic directed to men who read porn, who also might form a significant part of the comics public and who might not be married? In my mind, married or cohabitating readers with small children would be the prime demographic for, and the optimum beneficiaries of the cautionary aspects of, what lies within these covers. Then, are men the only audience for something that looks like porn? Questions and ironies multiply in Sammy Harkham’s strongest work to date.

________________________________________

*Another micropanel “how-to” in Blood of a Virgin explains the process of building an exploding head, using a model cast from the mold made of Joy’s head. Harkham made a short film with similar SFX that is online: at sammyharkham.com or at youtube.com.

________________________________________

Sources

George, Milo. “Moving Pictures:The Sammy Harkham Interview.” The Comics Journal #259. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 4/2004.

Harkham, Sammy. Crickets #3. LA: self-published, 2010.

Harkham, Sammy. Poor Sailor. Madera, CA: Ginko Press, 2005.

Harkham, Sammy. “Lubavitch, Ukraine 1876.” Kramer’s Ergot #6. Buenaventura Press, 7/2006.

Harkham, Sammy. Correspondence with the author, Feb 8-10, 2011.

McConnell, Robin. “Sammy Harkham.” Inkstuds: Interviews with Cartoonists. Greenwich, Nova Scotia, Canada: Conundrum Press, 2010.

Romberger, James. The Affordances of Parametric Images. Online at Comic Art Forum