I expected the 2012 Red Dawn remake to push jingoistic hyper-patriotic borderline-racist propaganda. And it does.

I did not expect it to carry a subtext urging a re-evaluation of the War on Terror. But it does that, too.

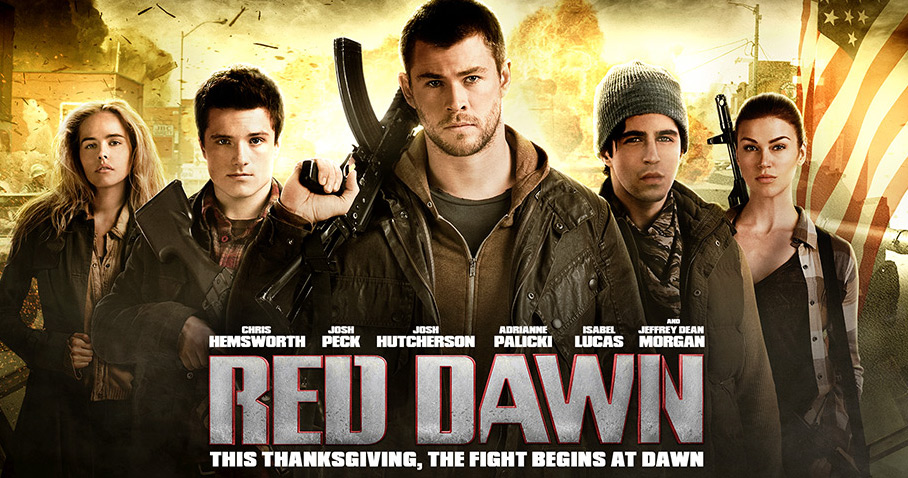

The original (1984) version of Red Dawn was a Cold War fantasy of Communist aggression and brave American teenagers heading to the mountains of Colorado as resistance fighters against a Russian/Cuban/Nicaraguan invasion. The kids call themselves the “Wolverines,” after their high school mascot. The remake keeps that same basic plot, except the leader of the guerrilla band is a marine home on leave after a tour in Iraq, the action has been relocated to Washington state, and the invading enemy is North Korea.

“North Korea?” one of the young partisans says, incredulously. “That doesn’t make any sense.”

“Well, there’s a bigger picture here,” his older brother replies, vaguely.

They’re both right. It doesn’t make any sense, but there is a larger bigger picture. That bigger picture might be called the real world.

In the real world of 2012, the United States was not being invaded — not in danger of being invaded — by North Korea or anyone else. We were, however, winding up occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan, two countries where we had faced ruthless, bloody insurgencies. What Red Dawn asks of its audience is that we imagine ourselves in the place of the insurgents.

“When I was overseas,” the Marine lectures, “we were the good guys. We enforced order. Here, we are the bad guys, and we create chaos.” The irony is cutting. For in the story the movie tells, it is obvious that these American kids, fighting for freedom, defending their homes, are the good guys; and what does that suggest about Iraq?

He also says:

“I don’t want to sell it to you, it’s too ugly for that. It’s ugly and it’s hard. But when you’re fighting in your own back yard, when you’re fighting for your family, it all hurts a little less and it makes a little more sense. For them, this is just some place, but for us this is our home.”

It’s the moment in the film when the subtext is most explicit, and it is so important that, with variations, the speech is repeated at the end of the movie. But there are numerous other points when the War on Terror makes its uncomfortable appearance. The Korean authorities, for instance, continuously refer to the rebels as “insurgents” and “terrorists.” They create an internment camp for suspect elements, dressing them in orange jump suits and using shipping containers for cells — like the Americans did at Bagram Air Base. Their propaganda and their oratory have an kitschy, cliched, Cold War aesthetic, but beneath the red veneer, there’s a standard hearts-and-minds kind of appeal. In their speeches, the occupying army insists that “We are not your enemies,” but liberators — bringing freedom, delivering security, and rebuilding the country. “Helping You Back On Your Feet,” one propaganda poster advertizes. “Repairing Your Economy,” promises another. What they ask in return is for “your cooperation in bringing these cowardly Wolverine terrorists to justice.” The rhetoric sounds hollow, but no more hollow coming from a Korean commissar than it did from Paul Bremer. The familiarity, as well as the falsity, seems to be part of the point.

Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised. Maybe the anti-imperialist role reversal was there in the original. Back in 1984, Andrew Kopkind wrote in The Nation:

“If you swivel the politics about 45 degrees to the left, Red Dawn begins to look more like a celebration of people’s war than a horror movie about the evil empire. . . . [Director John] Milius has produced the most convincing story about popular resistance to imperial oppression since the inimitable Battle of Algiers.”

Kopkind goes on to compare the Commies’ summary execution of unreliable elements to the CIA’s Phoenix Program, targeting Viet Cong supporters. He then suggests that we should “read Red Dawn as a parable of American intervention in Central America.”

Apparently the US Military didn’t get the memo. The 2003 mission to capture Saddam Hussein was codenamed, “Operation Red Dawn,” and the two sites the Army searched were dubbed “Wolverine 1” and “Wolverine 2.”

The point I’m trying to make has nothing to do with the dangers of a Communist invasion. It’s about propaganda and interpretation. Politics are sometimes a struggle over meaning, and such meanings are never really fixed or settled. But this observation raises more questions than it answers: Given that there is always the possibility for subversive subtexts and resistant readings, how does one produce or evaluate political propaganda? Is Red Dawn a right-wing movie, undermined and co-opted by left-wing critics? Or is it a left-wing movie cheered by conservatives too dumb to understand what they’re watching? Neither? Both?

And to what degree is the meaning created in the social practices surrounding the text, as opposed to residing in the movie itself? Do Blake’s “Jerusalem” and Springsteen’s “Born in the USA” become patriotic anthems because large groups of people treat them that way — “dark, satanic mills” and “the shadow of the penitentiary” notwithstanding?

Was Bradley’s more explicit 2012 Red Dawn a reclamation, a recompense for the US military’s tone-deaf and nuance-free embrace of the first film? Or are both films just object lessons concerning what happens when action movies try to be too clever — or when critics do?

Works Cited

William Blake, “Jerusalem [from Milton],” William Blake: Selected Poems. ed. Ian Hamilton (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 1994) 114.

Andrew Kopkind, “Red Dawn,” The Nation, September 15, 1984.

Red Dawn, dir. Dan Bradley (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 2012).

Red Dawn, dir. John Milius (United Artists, 1984).

Bruce Springsteen, “Born in the USA,” Born in the USA (Columbia Records, 1984).

Bio

Kristian Williams is the author of American Methods: Torture and the Logic of Domination, Hurt: Notes of Torture in a Modern Democracy, and an editor of Life During Wartime: Resisting Counterinsurgency.