Things about your writing you never want to hear:

“It’s just disturbing.”

“No, no, this can’t be.”

“That’s a little terrifying to me.”

And my all-time least favorite:

“How are people not going to hunt him down and harass him when this book comes out?”

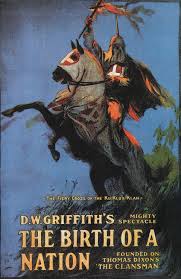

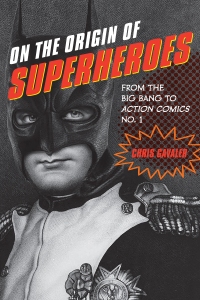

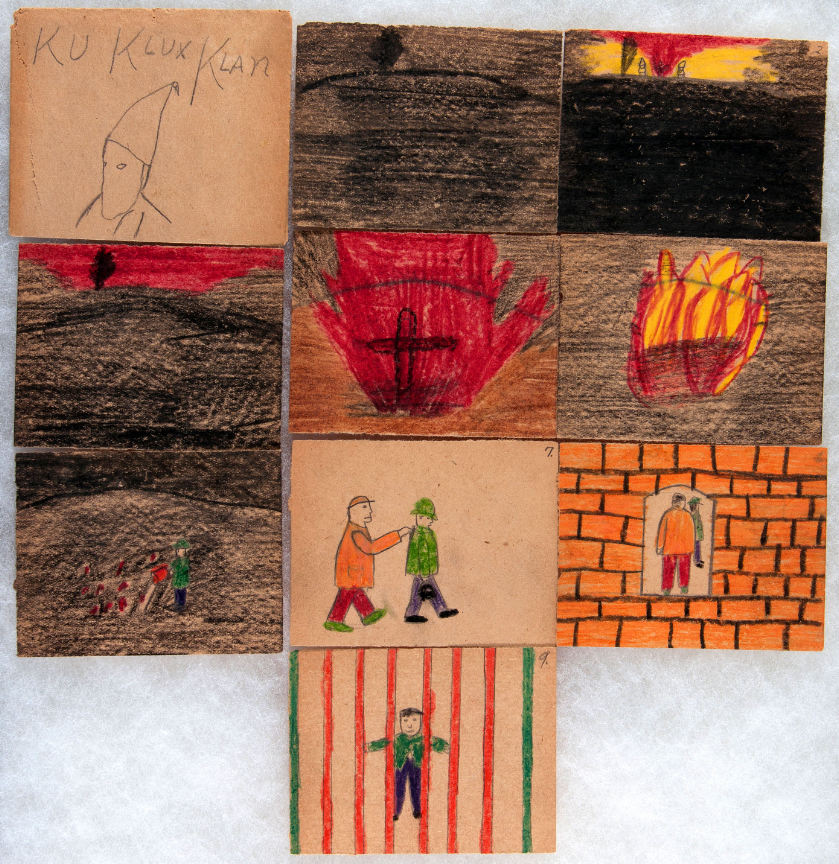

The book is On the Origin of Superheroes, due out next fall from the University of Iowa Press. You can probably guess it’s about the pre-history of the superhero genre, or, as the subtitle says: From the Big Bang to Action Comics No. 1. So that’s literally everything up until Superman, including—and this is the disturbingly no no hunt-me-down terrifying part—the Ku Klux Klan.

But first a major thanks to Major Spoilers. The comic book podcast recently interviewed superhero scholar Dr. Peter Coogan, and the conversation centered on my article “The Ku Klux Klan and the Birth of the Superhero.” It was published in England’s Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics in 2013, and its argument is part of the book: superheroes are descended from the KKK. Actually superheroes are descended from all kinds of things, and the Klan is just one of them, an idea Major Spoilers still found “hard to swallow.”

So did Peter Coogan when he first reviewed the essay, but he came around quickly, recommending that JGNC publish it: “This is one of those articles that once you’ve read it, it seems impossible to unthink it. I’m going to incorporate this idea into my teaching and my own work. I can’t believe I didn’t see this connection.”

Pete (we’ve since become friends) also warned me by email about his Major Spoilers conversation before it aired: “I wanted to give you a heads up because the hosts had a reaction that some of my students had, which is to feel uncomfortable about Superman having any genealogical relationship to the Klan. People just don’t like that idea.”

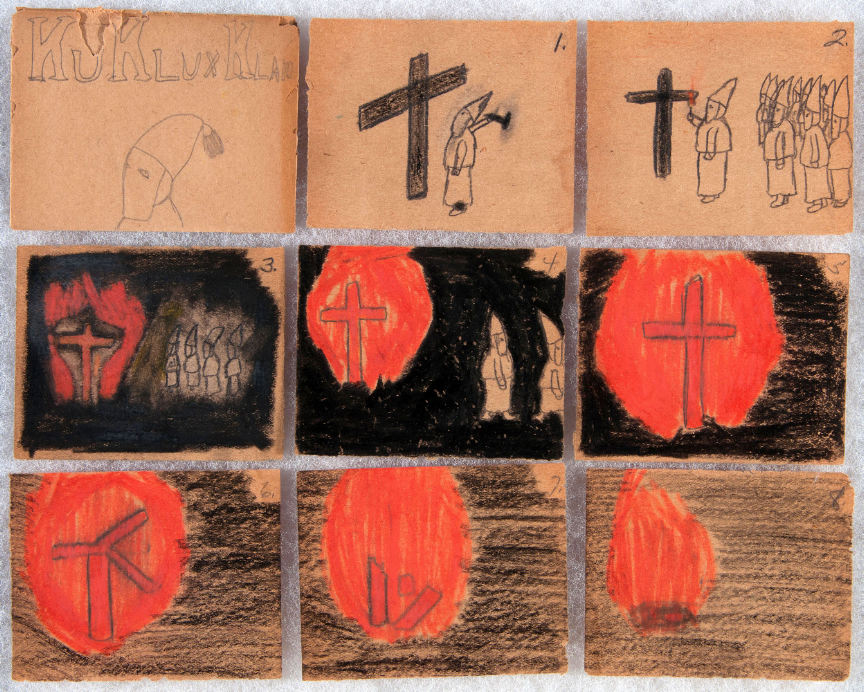

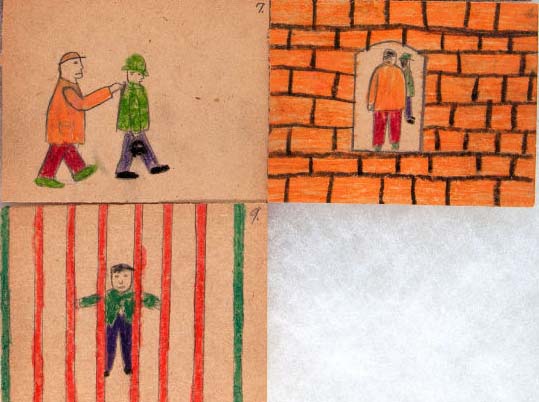

No, they really don’t. And I don’t either. The first time I introduced the notion in class, my students and I searched for every possible way to define superheroes in a way that excluded vigilantism. It’s hard to do. Secret identities, codenames, costumes, chest emblems, the KKK has them all. Pete tried too, arguing that superheroes only “supplement the police” and so “support legitimate authority” by “turning criminals over” after stopping them with “minimal level of violence necessary.”

And that does describe plenty of superheroes and proto-superheroes. The 70s Avengers even became a department of the U.S. government, each employee earning a tax-financed salary of $1,000 a day. As far as violence, the Lone Ranger’s creators Fran Striker and George W. Trendle were one of the first to lay down the law for their radio writers: “When he has to use guns, The Lone Ranger never shoots to kill, but rather only to disarm his opponent as painlessly as possible.”

But there’s a lot of violent gray zone. Martin Parker’s 1656 “Robbin Hood” didn’t kill, but he did merrily separate clergymen from their money and their testicles:

No monkes nor fryers he would let goe,

Without paying their fees;

If they thought much to be usd so,

Their stones he made them leese.

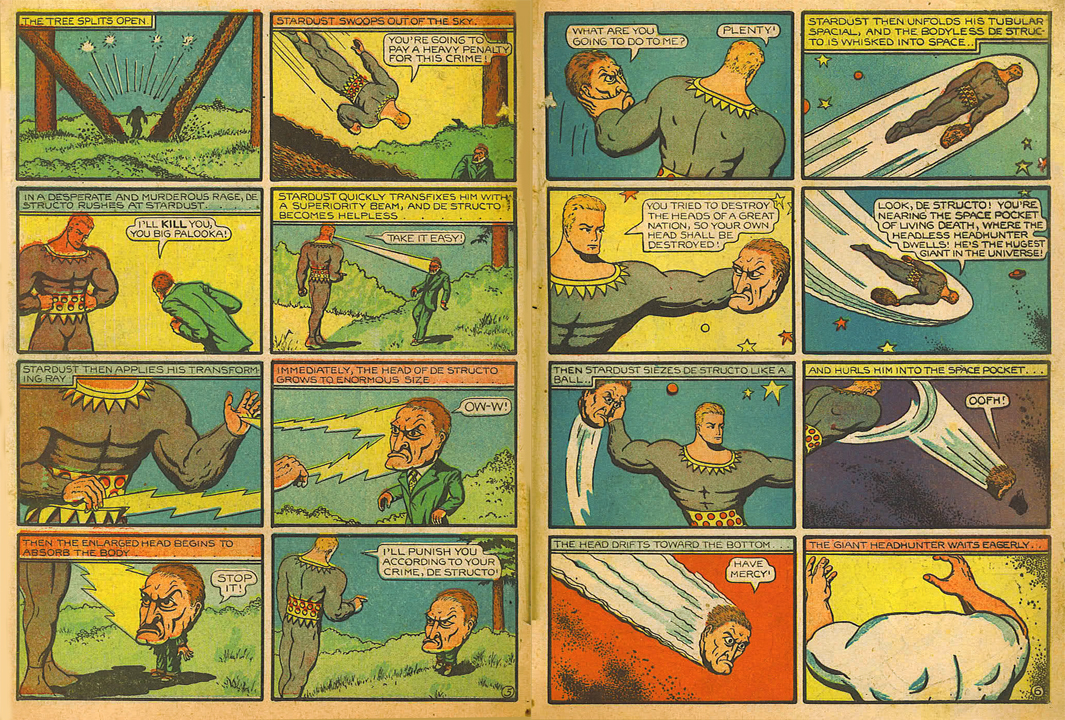

Worse, Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko considers superheroes “moral avengers” who must kill criminals in order to champion “a clear understanding of right and wrong,” even if that means violating the “pervading legal moral” code. Pete would place Ditko’s homicidal Mr. A with the 70s Punisher, who, like lots of pulp heroes of the 30s, constitutes his own one-man legal system, marshal-judge-executioner.

The problem is that ill-defined term “vigilante.” Instead of a toggle switch—either you’re a lawful hero or you’re a lawless villain—I see a spectrum. Spider-Man, like most superheroes, swings somewhere in-between, chasing crooks while cops chase him. But whether gunning down the bad guys or leaving them wrapped with a bow in front of police headquarters, superheroes are independent operators. Which means when they disagree with the law and the government, they make their own judgments. Even star-spangled super soldier Captain America turned noble criminal rather than obey a law that violated his own sense of morality. And while Iron Man backed the Superhuman Registration Act, it wasn’t from blind allegiance to his government. He backed it because he personally thought it was right.

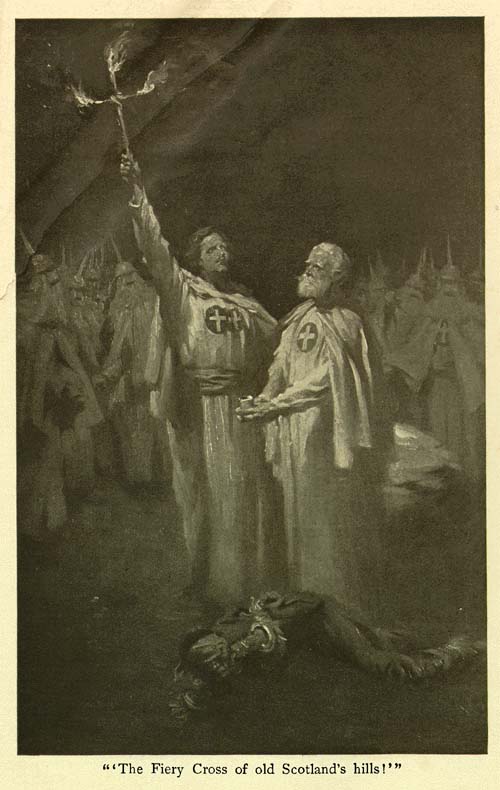

The KKK were the product of a very different Civil War, but their fictional characters in Thomas Dixon’s novel The Clansmen and D. W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation play by the same rules. Pete read aloud their mission statement on Major Spoilers:

“To protect the weak, the innocent, and the defenseless from indignities, wrongs and outrages of the lawless, the violent, and the brutal; to relieve the injured and the oppressed: to succour the suffering and unfortunate . . . “

Sounds like any superhero, doesn’t it? Until you get to the last phrase:

“and especially the widows and the orphans of Confederate Soldiers.”

“Hey,” said the hosts, “he tricked us!”

They eventually concluded that the difference between a hero and a villain is a matter of perspective, because probably even Lex Luthor thinks he’s helping the world. Pete also swooped to the rescue with Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and a superhero’s “ontological vocation of humanization.” In other words, a superhero has a deep calling to become more fully human and to help others to do the same. Clearly the KKK’s attacks and lynchings fail that criterion.

Pete’s point sounds exactly right, and the hosts “sighed a little bit of relief,” but for me this is where the Klan parallel is most disturbing. Even though Major Spoilers acknowledged that I am “not advocating for the Klan” and that I am “not saying superheroes are racist and fascistic,” Dixon and Griffith didn’t consider the KKK racist and fascistic either. Unlike Lex Luthor, who knowingly turns others into his tools and so is not helping them become more fully human, the Klan did not consider African Americans to be human. From Dixon and Griffith’s grotesque perspective, ex-slaves were subhuman obstacles preventing white Southerners from actualizing themselves. So in the most perverse reading of Freire possible, the KKK fixed the problem. In their minds and in the minds of their fans, they were superheroes.

Which is to say, yeah, please don’t hunt me down and harass me when the book comes out.