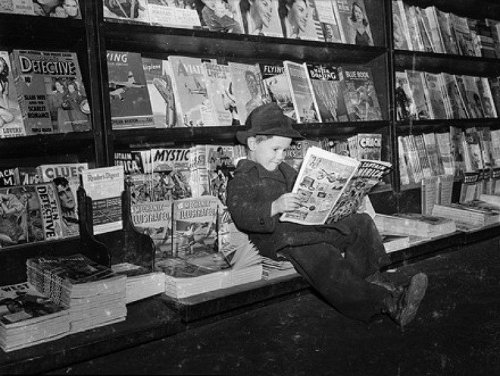

And on to comic books, in part four of our series on language

from the comics and cartoons!

“No, I haven’t finished clearing out the barn! I’m up to my eyeballs in chores– I’m not Superman, you know.”

Art by Joe Shuster

The creators of the Superman comics character didn’t invent the word ‘superman’, but its etymological trail is interesting in itself– again, comics set up a new usage for it.

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzche (1844– 1900) coined the word Uebermensch to decribe what he thought to be the necessary next step in the evolution of mankind.

He famously defined the Human (Mensch) as a rope between the Ape (Affe) and the Superman (Uebermensch).

Nietzsche himself became a comics character; art by Maximilien Leroy, after a script by Michel Onfray.

The word ‘Uebermensch’ translates literally as ‘above human being’.

Nietzche’s first English- language translator, Alexander Tille, rendered it as ‘Beyond-man’; but in 1909, Thomas Common translated it by taking the Latin root ‘super‘, meaning above or over, and added the Anglo-saxon ‘man‘.

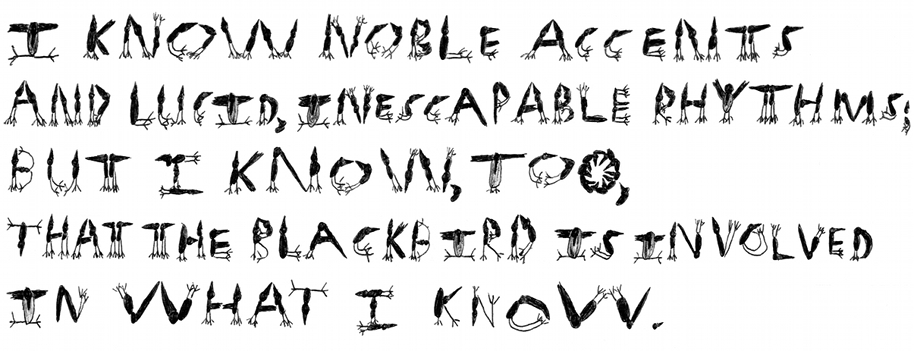

Here is an extract from an English version of Nietzche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus spake Zarathustra):

And Zarathustra spake thus unto the

people:

Behold, I teach you the Superman!

The Superman is the meaning of the earth.

Let your will say:

The Superman shall be the meaning of the earth!

Once,blasphemy against God was the greatest blasphemy; but God died, and therewith also those blasphemers.

To blaspheme the earth is now the dreadfulest sin, and to rate the heart of the unknowable higher than the meaning of the earth!

Verily, a polluted stream is man. One must be a sea to receive a polluted stream without becoming impure.

Behold, I teach you the Superman: He is that sea.

Where is the lightning to lick you with its tongue?

Where is the madness against which you should be inoculated?

Behold, I teach you the Superman:

He is this lightning, he is this madness!

Whew.

Next time, Friedrich, stick to the decaff.

“Sieh –Da! Dort oben im Himmel!” ” Es ist ein Vogel.” “Es ist ein Flugzeug!”

Nein– es ist UEBERMENSCH !!!

The idea was taken up by much of the intelligentsia of the late 19th century,and mixed with the ideas of Darwinism and Spencerism.

The ‘superman’ translation was popularised by the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw in his play, ‘Man and Superman‘, which actually predates Common’s usage by several years.

By the 1930s, a far more sinister twist on the superman concept accompanied the rise to power of the Nazis in Germany.

As part of their racist agenda, they talked about breeding a ‘master race’ of supermen.

To the Ubermensch they now contrasted the Untermensch, or sub-human, to be enslaved or destroyed.

A young Ohio science-fiction fan, Jerry Siegel (1914–1996), became fascinated by the idea of the superman, then much-discussed.

In 1933, in the pages of his mimeographed fanzine ‘Science Fiction‘, he published the short story ‘The Reign of the Superman‘ with illustrations by his friend Joe Shuster (1914– 1992):

In this tale, the Superman is a force for evil; as a Jew, Siegel understood the implications of Nazi philosophy.

(The Nazis were well aware of the Superman comic, and they viewed it with emotions varying from amused contempt– the magazine of the S.S.,Signal, published a nasty but witty takedown of the strip– to rage, apparently Goering’s reaction.)

Siegel and Shuster reworked the concept into a comic-strip; note, in this early version, that they retain the definite article: The Superman.

It was finally published as a comic book in 1938– and the rest is history.

Nowadays, we use the term ‘superman’ generally in an ironic sense.

In addition, the popularity of the Superman character has given rise to the use of ‘super‘ as an intensifier. Shops offer us ‘super savings‘, for example; since 1944, a superpower is a state with overwhelming military or economic superiority over other countries; where Hollywood once had mere stars, it now has superstars.

(Contrast this with the traditional use of the ‘super’ prefix keeping its sense of ‘above’ or ‘over’, as in supervise, supersede, superfluous, superannuated, etc.)

In Britain, “Super!‘ became an exclamation of admiration on the order of “Great!” or “Terrific!”

We’ve come a long way from Nietzche! And, in fact, when the latter’s work is discussed by scholars today in English, the untranslated term Ubermensch is used.

In the 1950s, a new translation by Walter Kaufman introduced the term ‘overman’; Kaufman fumed bitterly at how ‘superman’ had been co-opted by Pop culture. Wie schade!

“Perhaps they calculated that winning health care would strengthen them for climate change, like Popeye after a helping of spinach. But the political effect, at least in its immediate manifestations, was more like kryptonite.” — Hendrick Hertzberg, The New Yorker, Feb 7 2011.

Of course, Superman has a dread weakness: the mineral kryptonite is deadly to him.

(Green kryptonite, that is; as every scholar knows, there are five colors of kryptonite, each with different properties. I publish the following guide as a public service for today’s woefully ignorant youth:)

(Interestingly, kryptonite originated not in the comic, but on the popular Superman radio show.)

That same radio show also gave birth to expressions such as ‘faster than a speeding bullet’ and ‘Up, up and away!‘)

Kryptonite’s powers are so famously dangerous to the Man of Steel that the word has passed into common speech to indicate something strongly repellent.

Art by Wayne Boring and Charles Paris

The Kryptonite line of bicycle locks is supposed to deter thieves, for example:

” John’s a fairly good student, but his sister Anne is the real brainiac of the family–chess club, computer club, honors roll…”

Art by Curt Swan and Stan Kaye

One of Superman’s deadliest foes is the evil android Brainiac, a super-genius, first appearing in 1958.

Brainiac is also high-school slang for an exceptionally intelligent student.

Did the slang term come from the comic book? The jury’s out on this one.

Brainiac was also the name of a kit computer for students, introduced in 1956; the name obviously derives from early computers such as Univac.

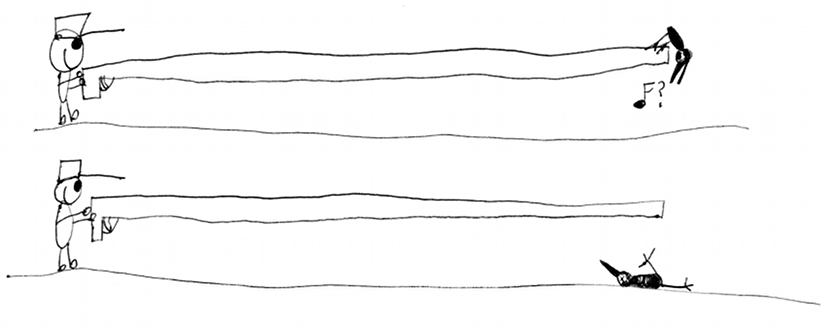

Now, in the panel below, note the strange caption at the bottom.

Art by Curt Swan and George Klein

‘Brainiac is also a trademark registered by Berkely Enterprises, Inc, manufacturers of the famous “Brainiac Computer Kit.” See Metropolis Mailbag, in this issue, for details.– Editor’

What happened? Berkely Enterprises, the manufacturer of the Brainiac kit, made some nasty legal overtures to DC Comics over trademark infringement.

The publisher managed to soothe the irate computer-maker with a nice dollop of free publicity.

So — did the ‘brainiac‘ appellation come from the computer or from the comic?

I’ll bet on the latter (and so will the dictionaries)… but who knows for certain?

(For the full story, go to Brian Cronin’s thorough reporting here, my source for this usage.)

“It’s some kind of bizarro flu bug– my doctor can’t make head nor tail of it”

The use of bizarro as an adjective dates to the early 1970s, though the comic-book Bizarro and his Bizarro World came about in the 1950s in the pages of Superman; the Bizarros had their own series in Adventure Comics.

Art by John Forte

On Bizarro World, everything is backwards, according to the Bizarro creed:

Did the slang use come from the comic, or is it just an extension of the word “bizarre” — as ‘weirdo’ is from ‘weird’?

Probably the latter– although the Bizarros became prominent when championed by their fan Jerry Seinfeld on his hit T.V. show, Seinfeld, in the ’90s:

Elaine: “He’s reliable. He’s considerate. He’s like your exact opposite.”

Jerry: “So he’s Bizarro Jerry.

Elaine: “Bizarro Jerry?”

Jerry: “Yeah, like Bizarro Superman, Superman’s exact opposite, who lives in the backwards Bizarro world. Up is down, down is up, he says hello when he leaves, goodbye when he arrives.”

Elaine: “Shouldn’t he say badbye? Isn’t that the opposite of goodbye?”

Jerry: “No, it’s still goodbye.”

— from the Seinfeld episode, ‘Bizarro Jerry”

*************************************************************

“I love the microwave oven. You press a button, and shazam! Instant cooked dinner.”

Superman’s big rival was Captain Marvel, ‘the World’s Mightiest Mortal’ — who actually outsold the Man of Steel in the 1940s; this irked National (DC), Superman’s publisher, who sued its upstart rival out of existence.

Captain Marvel’s alter-ego, Billy Batson, transformed into the superstrong ‘Big Red Cheese’ by shouting a magic acronym formed from the names of Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles and Mercury: SHAZAM!

Superman figure by Murphy Anderson; Billy

Batson and Captain Marvel by C.C.Beck

(The above cover shows that rivals can kiss and make up; in 1972 DC leased Captain Marvel from its owner, Fawcett Publications.)

At any rate, ‘Shazam!‘ became a magic formula, akin to ‘abracadabra’, hinting at an instant transformation. The word got a big boost in the 1960s as the favorite exclamation of T.V.’s Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C, acted by Jim Nabors, and in the 1970s from the Shazam! kid’s television show.

“Nine o’clock already? Holy Moley! My wife’s gonna kill me!”

Captain Marvel’s own favorite exclamation was ‘Holy Moley!‘ I was surprised to find that this now-common idiom, which I thought predated the comic, apparently originated with it.

Cover by C.C.Beck

It’s possible the editors at Fawcett didn’t want to use the common ‘Holy Cow!’,’ Holy Mackerel!’ or ‘Holy Smokes!’, aware of their blasphemous connotations (the first two insulting the Virgin Mary, the third insulting the Holy Ghost), and thus elected to invent their own meaningless but euphonic utterance.

“If I were you, I’d stay as far away from the police as possible. What do you think they’d say when they saw that outfit, Mary Marvel?” — John Kennedy

Toole, A Confederacy of Dunces

Captain Marvel had a little sister:

Art by Jack Binder Studio

To understand the quote from the Toole novel, consider the scene: the hero, Ignatius O’Reilly, has been forced into a job selling hot dogs, and has to wear a ridiculously camp pirate costume. The speaker of the quote is a Gay man taunting him about his outfit. But why ‘Mary Marvel’?

I go online to a dictionary of Gay and LGBT slang, and find this on the use of ‘Mary’:

1. An effeminate homosexual male, as used by other homosexuals to affectionately

“nickname” him. The term is very widely used, sometimes mockingly (indeed,

perhaps, “self-mockingly”). It is a greeting “Mary! How are you, dear?”

In its adj. form, “Is she ever mary,” it states that the male

homosexual is very feminine. It is also the one word that “slips out” when a

homosexual is vexed with himself or what he is trying to do; instead of,

perhaps, “O damn…!” it’s “Mary…!”.

2. A male homosexual who takes the passive, feminine role.

3. A lesbian.

4. A woman – no negative connotations.

5. (gayle slang) Obvious homosexual man.

6. A term of endearment or greeting: “Hi Mary!”. Also, a standard camp

name used by gay men to refer to each other.

It seems to me that “ Mary Marvel” is a variant on simple “Mary”, and that definition number 1 applies here.

A Gay friend informs me that the usage is now obsolete, but the same doesn’t apply to a certain Dynamic Duo’s place in Gay terminology… as we shall see in part 5 — where we also encounter the Lone Ranger, Vladimir Putin, Baby Huey, Dr Wertham, Alfred E. Neuman, Tubby, Wikileaks, and Zippy the Funny Pinhead .

Be there– or be square!

******************************************************

This is part four of a seven part series; click here for part 1, part 2 and part 3, dealing with American newspaper comic strips; part 5 , like this part, looks at comic books; while part 6 concerns gag panels and editorial cartoons; part 7 covers British cartoons; and there’s an index.

I would like to have a part 8, consisting of French, Italian, and other European colloquial languages enriched by their cartoons.

If you have any suggestions for cartoon-derived idioms along the above lines, please mention them in comments– or e-mail me at the yahoo dot com address alexbuchet

***********************************************************

An incredibly massive resource for research on comic books is The Grand Comicbook Database. Lots of cover eye candy in addition to information on over 200 000 comic books.

Brian Cronin’s charming column, Comic Book Urban Legends, features thousands of offbeat facts; much of it is superhero trivia, but he also speaks of strips and panel cartoons. Many thanks for his info on the Brainiac affair.

The online gay and LGBTglossary is my source for the Mary Marvel material. A window into a robust and expressive jargon.