I just got my hands on a copy of Rutu Modan’s The Property after reading some good reviews of it online here and here. Modan is one of those artists who people always seem to describe in terms of her sensibility, and I can see why. She has a singular way of treating heavy subjects with a visual brightness in her coloring and use of clear line, and a levity in her writing of dialogue, that brings the tragic into contact with the everyday without diminishing the reality nor the importance of either. Much like her last long-form graphic work, Exit Wounds, the story recognizes the power and importance of the past without wallowing counterproductively in it, or misappropriating it.

The story follows Mica and her grandmother Regina as they travel to Warsaw to recover property lost to their family during WWII. As soon as Avram, the nosy Israeli acquaintance, Tomasz, the sexy but suspiciously philosemitic Pole, and Regina’s old flame, Roman, enter the scene, a series of omissions and half-truths turn the story into a dark comedy of errors. Mica winds up in a perverse reenactment of a Nazi roundup in the Warsaw Ghetto, she argues with family members she doesn’t realize are family, and she’s mistakenly led to believe that she will inherit a Hilton property. The past always looms present but not always as truth. Modan explains in an interview with Marc Sobel for The Comics Journal that she made the deliberate decision to divorce Regina’s story from those of the Polish Jews who endured the horrors of the war by having her emigrate to Israel with her parents before the war. As Modan explains it, all of the characters in The Property, aside from Mica, have a bad faith relationship with the past and seem bent on trying to exploit it for some form of personal gratification:

MODAN: In the story there is this old couple who are trying to feel again what they lost 70 years ago, and there is the Society of Jewish Memorialization trying to make kids experience the horrors of the war, and these Israeli high school kids going to visit the concentration camps like they go to some twisted summer camp, and Tomasz who’s trying to do a graphic novel, dreaming it would become the Polish Persepolis… everyone, except for Mica, the heroine, is trying, in some way, to revive the past.

SOBEL: But even she is going back to reclaim the property…

MODAN: Yeah, but this is what I think happened to Mica in the end. She does connect to the past, but it’s by giving up the property, not by getting the property.

The past matters to Modan but perhaps because, being Israeli, “connecting with the past” is too closely tied to coercive political rhetoric, Modan’s heroine is only able to make an authentic connection to the past by abjuring any claims to personal gain from it.

What I find most extraordinary about Modan’s artistic sensibility is how she approaches morally complex questions through richly colored ligne claire drawings (in notable contrast with Tomasz’s colorless cross-hatched drawings in the comic-within-the-comic). Glen Weldon’s review of The Property describes her use of ligne claire nicely: “Modan’s deceptively clear and simple line work — she can conjure a face in two dots and a single, expressive pen stroke — is a deliberate artistic choice […] Her clean and often brightly colored illustrative style serves in part to lift the fog of war, allowing us to see these conflicts, be they emotional or military, with new eyes.”

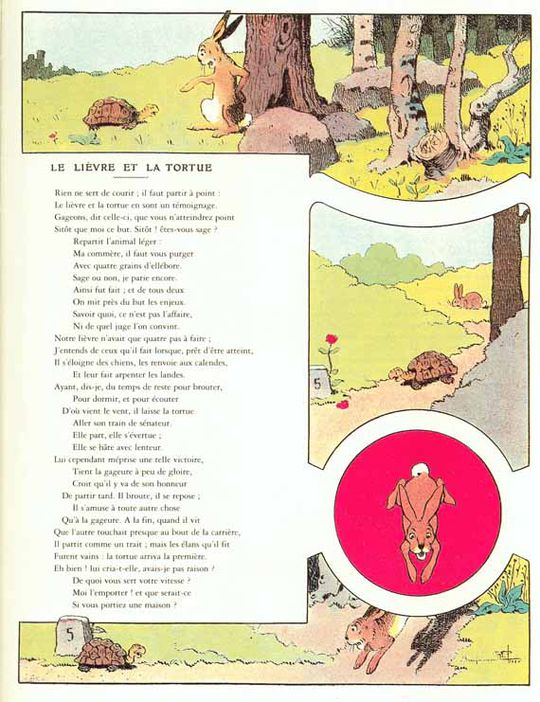

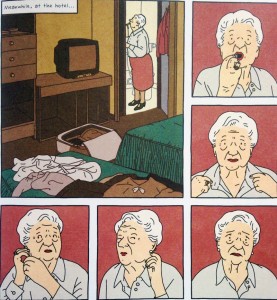

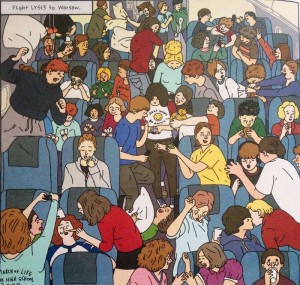

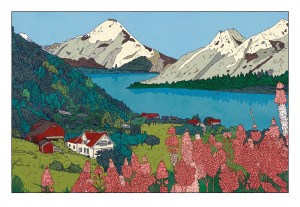

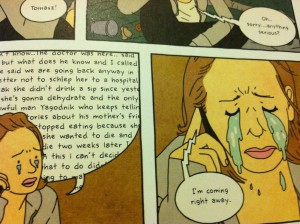

For Modan, the clear line is both a form of irony (i.e. reality isn’t so clear) and of observation, focusing the reader’s attention on human expression without the seduction of bad-faith historical realism. Unlike many comics in the ligne claire style, Modan’s clean line does not shy away from awkward embodiment just as her narrative refuses to shy away from awkward misunderstandings and cross-purpose communication. Modan’s clean line, in concert with her hyper-observant eye for human expression and the grotesquerie of embodiment, aligns her work with the surreal. And if you look at some of her illustrations and non-narrative comics, also in the ligne claire style, it’s clear that she has a surrealist sensibility (see the first two images below). Modan’s surrealism creeps in narratively, for example, during the reenacted Nazi roundup, but also visually in a panel showing Mica crying in which her tears appear like Lichtensteinian waterfalls on her cheeks (see Mica’s tears juxtaposed with Lichtenstein’s famous I Don’t Care! I’d Rather Sink below). Also, in Modan’s case, clean line drawing does not necessarily mean clean panels. The cluttered sensuousness and vibrant color palette of many of Modan’s panels betray a punk (I’m thinking Julie Doucet) and a pop art sensibility (see the two panels above showing the crowded flights to and from Tel Aviv). Of course, pop art drew much of its inspiration from the ligne claire style in comics, advertising, and illustration. And Modan is not unaware of this irony. In fact, this layering of visual histories and appropriations appears to be the visual correlate of the historical narratives Modan works with, a layered and endlessly contested space where she seems to be very much at home.

.jpg)