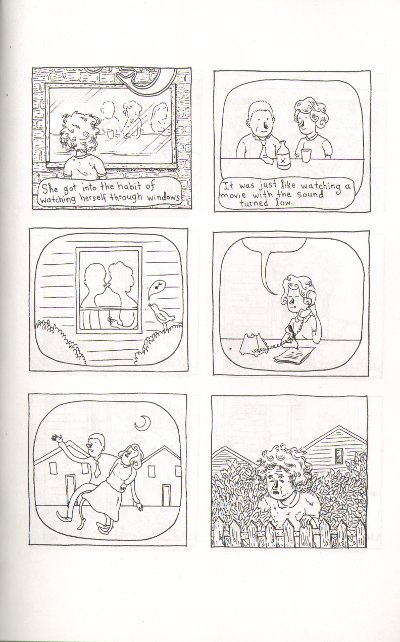

There’s a moment in Lilli Carré’s minicomic “The Thing about Madeline” where you really get that you’re reading a real story and not another installment in the Saga of the Mundane. It’s a little later than the point where that story actually begins: not where Madeline meets her doppelganger/self for the first time – that’s just a plot twist – but when Madeline the First gets “into the habit of watching herself through windows”:

Robert Stanley Martin correctly identified this moment as the place where the story’s main narrative idea slips from metaphor into dramatic irony, as the doppelganger is able to find the happiness in her life that Madeline could not. His review is so spot on I’m just going to link to it rather than trying to cover those aspects of the narrative myself.

But those panels also mark the place where the visuals take over doing that metaphorical work that the narrative leaves behind: the images of double Madeline continue to manifest the theme of alienation from oneself and one’s life while the plot (and facial expressions) hold up the ironic narrative.

What’s particularly beautiful and satisfying about this is not just that the visuals effortlessly carry significations that would become increasingly labored in prose. It’s also that the comic itself is now doubled right along with Madeline: the themes of alienation and happiness continue side-by-side formally in the same way that Alienated Madeline and her Happy Doppelganger populate the narrative. What this allows, then, is two separate story arcs: a literal one about Madeline and the Doppelganger, and a sustained metaphorical one about the relationship between alienation and happiness. Toward the end of the book, when Happy Madeline is visited by her own Alienated Doppelganger, the scenes from the beginning are recast – on a second read or in retrospect, it’s possible to see Happy Doppelganger and Happy Madeline as the same “character.” In that reading, self-alienation is always lurking and, as Robert points out, the easy moralizing criticisms of Alienated Madeline are much harder to make. The powers of circumstance and perspective get attention in a way they could not if the story had stayed more personal, eschewing that metaphorical strand.

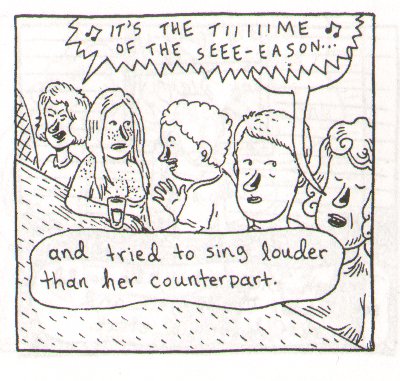

Carré’s work always balances very deftly on the line between ironic detachment and literary self-awareness, both traditional dramatic irony as well as the more formalist kind. Her characters often have these very distinctive noses that are a mashup of Mary Poppins and Raggedy Ann, and they alone are sufficient to make her drawing style immediately recognizable. In the case of The Thing about Madeline, this stylistic quirk works as support for the formal edifice: they mark the characters as “drawn,” and the effect of this signature is to anchor those characters to the visual plane of the comic. They restrict the universality of the characters and contribute to our sense of detachment from them.

That signature nose is absent from Carré’s most recent animated film, Head Garden, one of the selections for the 2010 SPX Animation Showcase.

Head Garden from Lilli Carré on Vimeo.

Instead, the face carries the metaphor, more directly. The facial features are less “cartoony” and more influenced by “art” faces like the ones discussed here and in comments. For me, the loss of this creative “signature” lets the animation breathe and allows the critical, slighly neurotic self-awareness of ironic detachment to mutate into the genuine double entendre that marks the best literary characterizations. The physical marker of style is less overt, but there is no loss of metaphorical sophistication (relatively at least; the animation’s metaphors are less ambitious than the mini-comic’s). The characters have become less “self-conscious”, although less well-developed in this less narrative piece, and I think because of this, the seams between the form and its significance are better hidden. I don’t think that’s just an effect of the film as opposed to comics. Identification with these characters is less detached even in still frames, despite the much more distant narrative characterization.

It seems to be a one-off, though; Nine Ways to Disappear maintains the signature style, as do Carré’s previous animations. (The nose is put to exceptional effect in What Hits the Moon; watch the way it sustains the character’s identity as her face ages around it.) But I think the comparison illustrates some of the limitations of too much “handwriting”: after awhile, it begins to feel like deliberate self-citation. Unless the handwriting is used in some meaningful way, it can interfere with other effects. Head Garden is still discernably Lilli Carré, but in the absence of that distinctively marked facial feature, her graceful but slightly awkward lines — like the talented too-tall girl in ballet class — get to take center stage. I hope to see a sustained story from her in the style of Head Garden sometime soon.

=========================================================

This review is based on the black-and-white mini-comic version of The Thing about Madeline. More information on the SPX Animation Showcase is available here.