____

This is part of the Gay Utopia project, originally published in 2007. A map of the Gay Utopia is here.

Tag Archives: Lilli Carre

Comics Turning Into Art…Or Not

This appeared a while back at the Chicago Reader

Comics are part of visual art — sort of. There aren’t too many comics pages in permanent museum collections…but on the other hand gallery shows featuring comics artists are more and more common. The MCA’s “New Chicago Comics” helps to explain why comics don’t and do fit on museum walls. On the “don’t” side is the work of Jeff Brown and Paul Hornschemeirer, both artists whose focus is insistently narrative. Brown especially, with his crude drawings and layouts and cutesy punch lines, doesn’t benefit from the venue’s close focus. Works by Anders Nilsen and Lilli Carré, on the other hand, seem liberated by being lifted out of their original context. A Nilsen page showing six panels of a small pigeon cursing in darkness before it suddenly sees a cave full of blind birds is not diminished by the fact that you don’t know where the story goes. On the contrary, it leaves you, like the pigeon, trapped in a mysterious subterranean landscape, where there is wonder and life but no escape. Similarly, Lille Carré’s stencil-like drawing Splits, showing a stylized woman in a teapot almost touching her own duplicate, folds comics’ panel-to-panel repetition back on itself. It’s as if a character turned around, saw herself across the gutter, and was instantly transmuted into art. The MCA show provides an interesting contrast between some comics which can’t, and are perhaps not even interested in, making that turn, and some which can and do.

Women In Comics

Just wanted to mention that I’m friends with both Lilli and Derik, but somehow writing about their work here it seemed weird to use their first names. So I didn’t. Hopefully they won’t be offended!

_____________

A bit back I talked about Bart Beaty’s claim that comics have been culturally gendered feminine in relationship to high art. As I said in my post, I don’t find Beaty’s argument entirely convincing. In the first place, high art is itself often gendered feminine (and often mocked as such.) And, in the second place, after thinking about it more, it seems like comics are more often associated with children than with the feminine per se. Children are, of course, often associated with femininity themselves, since traditionally raising children is women’s work and also because anything not-man (whether it’s women, boy, girl, or a horror-film pile of undifferentiated slime) often gets lumped together as “feminine.” Still, it seems worth noting that comics’ femininity seems like its arrived at through a series of somewhat abstracted substitutions. In terms of culturally coded femininity, comics isn’t needlepoint.

Still, just because comics aren’t usually directly associated with femininity, that doesn’t mean that artists can’t treat comics as feminine, or play with the idea of comics as feminine.

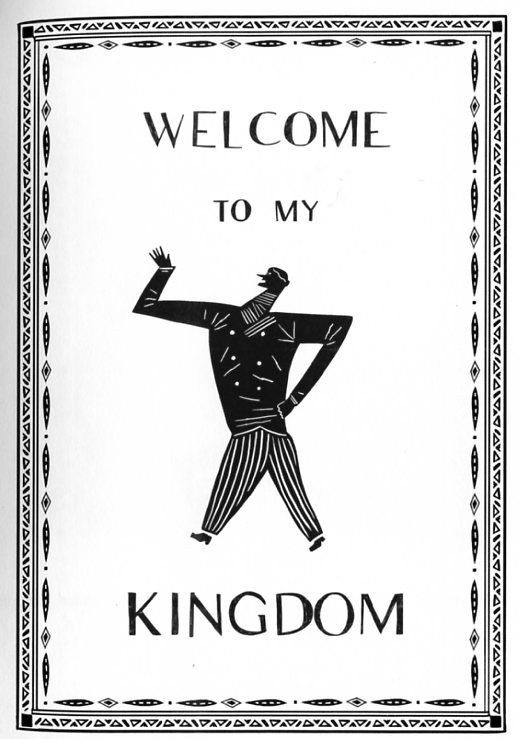

For example, consider the short story “Kingdom” by Lilli Carré, included in her recent Fantagraphics collection Heads or Tails. The story starts off with a well-dressed fellow celebrating his expansive masculinity inside a high-art picture frame.

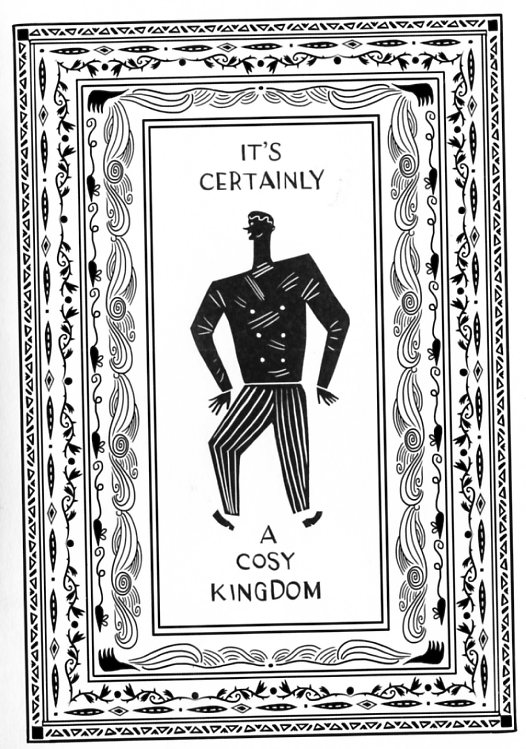

Page by page, though, new detailing and fringes are added to the inside of the frame, till the wide masculine range becomes a hemmed in, overly-crafted cozy feminine interior

And finally the man himself is reduced to a stylized decorative element. Instead of master of all he surveys, he is an object — or, rather, a surface, surveyed.

Again, the border here looks, and is surely intended to look, like a picture frame, and so the shuffling of gender is also a shuffling of the gendered connotations of fine art. On the one hand, high art is (as Beaty says) seen in its performative, striding creativity as a masculine kingdom — a canvas over which total control can be exercised in the interest of totalizing self-expression. At the same time, though, the detailed handwork and patterning associated with art — its prettiness, or fussiness, or surfaceness, or frivolousness — links it to the femininity of the craft fair.

If art is both hyperbolic masculine swagger and small-scale feminized detail, though, for Carré the form that mediates between the two is something that looks a lot like comics. The border in Carrés story is a frame…but, from page to page, it’s also a panel. So, on the one hand, the progression of the story could be seen as going from the least-decorated, most comic-like panel at the beginning to the most-decorated, least comic-like panel at the end — or, alternately, the initial image could be seen as a single picture frame, while the additional images emphasize more and more the sequential comic nature of the story. Thus, comics can be either a masculine form feminized by high-art frippery…or a feminine form which pulls high art down into the crafty feminine repetition of surface details.

Carréis herself a female artist who works in both the traditionally male-dominated art world and the traditionally male-dominated comics world. As such, she is, it seems, gently tweaking the masculine pretensions of both — or perhaps tweaking her own attraction to the masculine pretensions of both. That tweaking is performed in part by deploying comics as the feminine alternative to high art — and high art as the feminine alternative to comics. Both comics and high art, in other words, are only nervously, unstably masculine, and that instability is, for Carré, not so much a danger or a weakness as it is a potential — a way for masculine and feminine, art and comics, to open out and lock together in a single claustrophobic, vertiginous spiral.

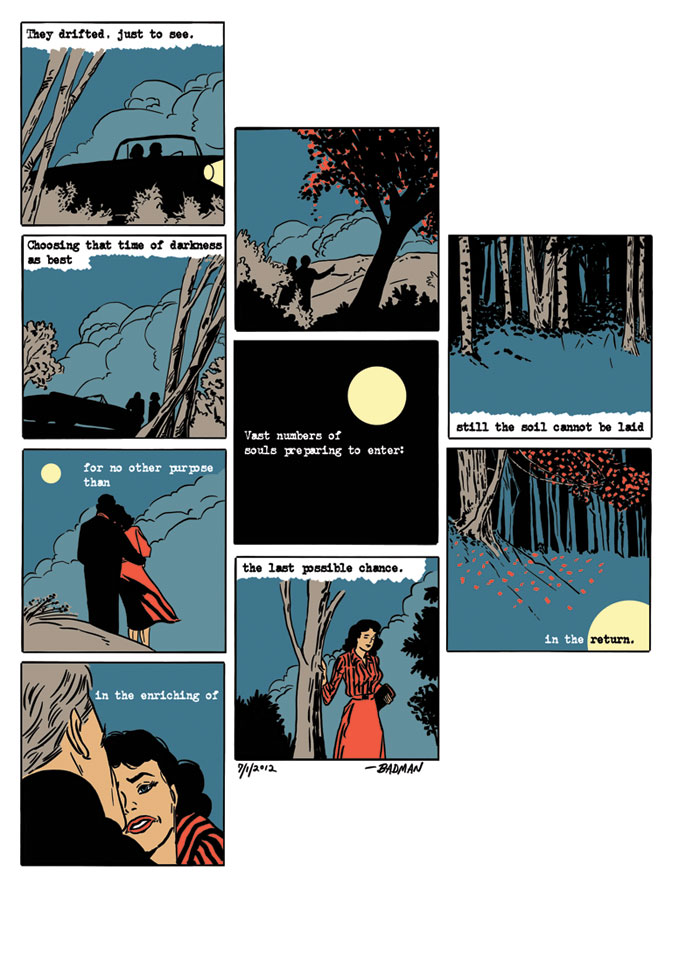

Derik Badman takes a very different approach to comics as feminine. In the anthology Comics As Poetry, Badman channels pop art in a series of ambiguous pages.

Lichtenstein mostly used single panels drawn from comics for his canvases — he ironized melodramatic narratives by pulling single moments out of them, and so highlighting their generic artificiality. There’s a little of that in Badman’s version too; the off-kilter columns of images make the narrative flow uncertain — the panel sequence is almost arbitrary. You can read left to right or top to bottom, or even in some sense randomly around within the page.

Again, you could argue that the effect here is something like mockery and something like appropriation; taking the feminized tropes of romance comics, hollowing them out, and presenting the remains as a de-emotionalized, high-concept masculine avante garde. As I’ve written before, though,I think that reading does a disservice to Lichtenstein, and I think it’s not really fair to Badman either.

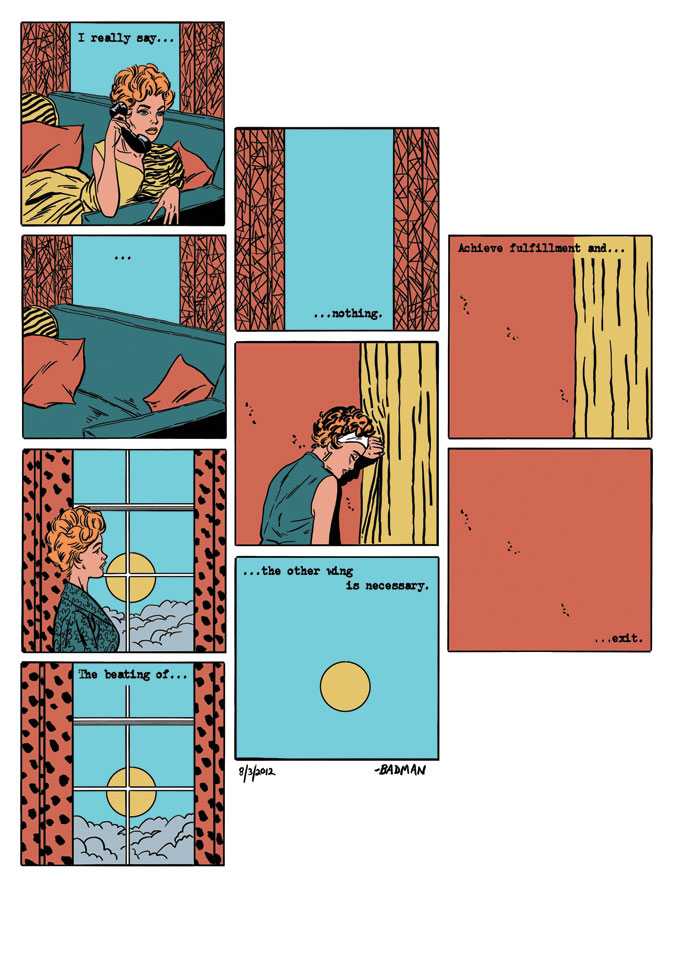

Rather, in Badman’s case, it seems less like the high art avant garde masculinizes the melodrama than like the melodrama reveals the true, feminized emotionalism of the avant garde. In the page below for example:

The first panel, with the telephone, becomes a kind of synechdoche for the entire page, thematizing an illustory connectedness which emphasizes a greater absence or distance. The ellipses trailing off or trailing in, to which panel or from which panel is never clear, similarly hesitantly underline the way each panel comes out of and goes into white space…comics not as Charles Hatfield’s art of tensions, but rather as an art of slack disconnection. The desire to make meaning of the narrative — to have “The beating of” connect to “the other wing” — is also the desire or loss of the woman — or perhaps of the women, plural, since the identity of multiple images is one of the comic conventions of continuity that here breaks down into the overarching convention of discontinuity. Comics multiplies bodies, and multiple bodies is desire. The avant garde lacunae, the resistance of interpretation, becomes, not anti-narrative cleanliness, but — through the mirror of comics’ formal elements — a hyperbolic extension of narrative’s most febrile excesses of deferment and longing.

Badman, then, seems to out-Beaty Beaty, inasmuch as, in this reading, comics is not just culturally feminized in relation to high art, but is actually, formally feminine. Indeed, that formal femininity is so overwhelming that it starts to absorb not just comics, but everything connected with comics — not least of all Pop Art. Badman’s comics almost demand to be viewed, not as cut up panels of comics, but as conglomerations of pop art images — and in creating those conglomerations, he makes it hard to see pop art as anything but conglomerations. Lichtenstein’s canvases…are they really isolating images from a narrative? Or, instead, are all those isolated images trying but failing but trying to talk to each other, so that all of Roy Lichtenstein’s panels end up, not as bits from different comics, but as their own single melodramatic discontinuity? For that matter, when you go to a gallery or a museum, each piece isolated in it’s own frame — doesn’t that isolation, that disconnection, that yearning gap, make the high art more comics than comics, and therefore, formally, more feminine than feminine?

For Badman, as for Carré, then, the binary art/comics doesn’t so much map onto the binary masculine/feminine as it creates an opportunity to think about binaries and gender. In the work of these two creators, comics and art want each other and want to be each other and want nothing to do with each other, and certainly too, are each other. So, too, does male/female close in upon itself and empty out of itself, a folding, unfolding box holding and releasing form and desire.

Lilli Carré’s The Fir Tree

This first appeared at the Comics Journal.

_________________________

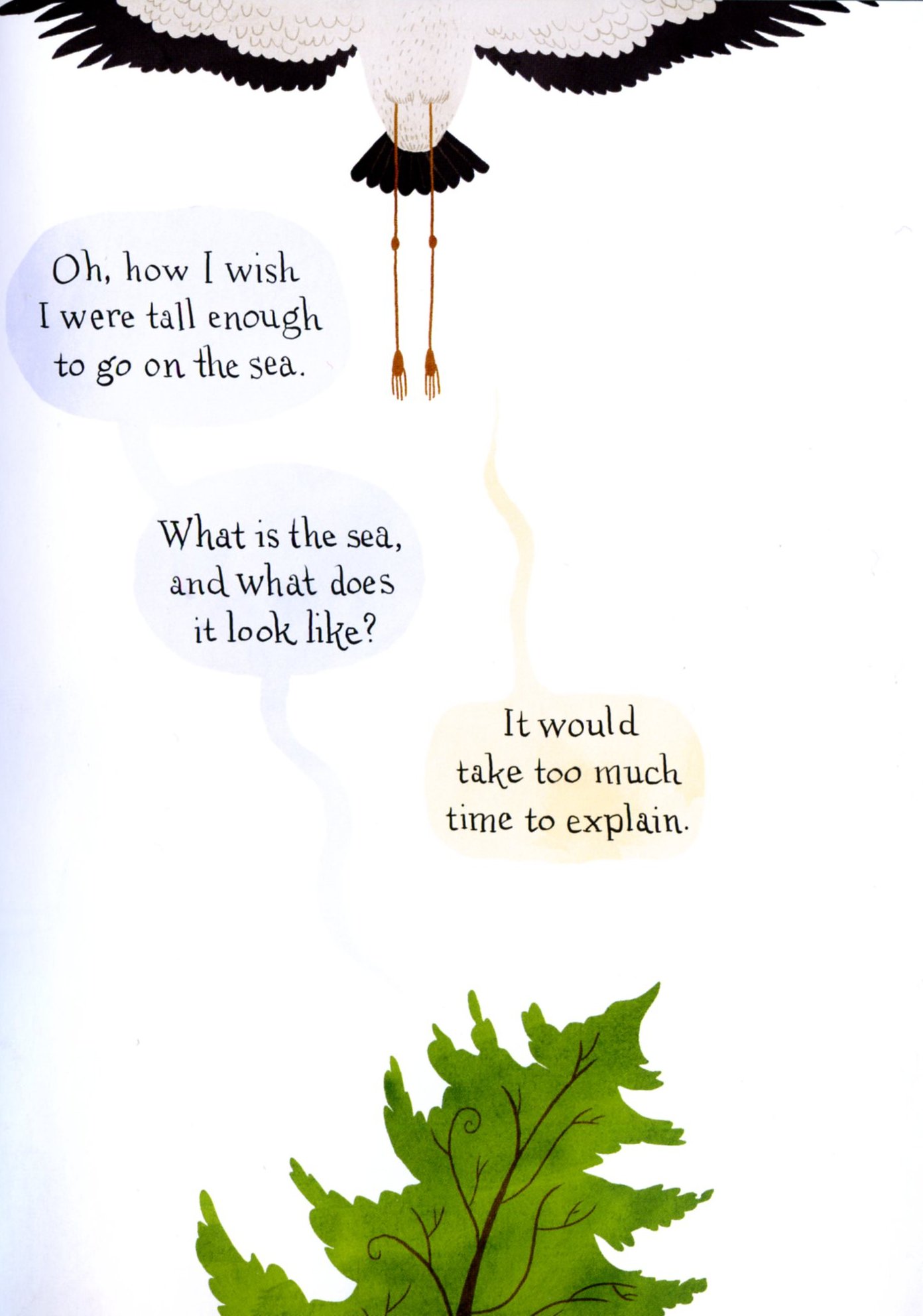

Lilli Carrés version of Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Fir Tree” functions in general as an illustrated books…but there are many moments which showcase Carrés familiarity with comics. One of the most memorable of these is a page that shows our protagonist, the fir tree, talking to a stork. The layout makes dramatic use of white space and of bleeds; the tree is at the bottom, its lower two-thirds chopped off by the edge. The stork is dead center at the top, its wings spread majestically, its legs extended straight out below it, and its head cut off by the top of the page. In the space between bird and fir, three pale speech bubbles are arranged in a graceful curving tier. The fir’s words reach up on the left-hand side, as if trying to follow the stork up, up, and off the page: “Oh, how I wish I were tall enough to go on the sea. What is the sea and what does it look like?” And on the right, floating down negligently, as if casually dropped, the bird’s speech bubble replies, “It would take too much time to explain.”

I know folks swear by Chris Ware’s complicated virtuoso every-which-way page layouts, or by J.R. Williams’ dense formalist virtuoso page layouts, or by Dave Mazzuchelli’s archly formalist virtuoso page layouts. And, you know, I can appreciate all of those too. But simplicity can be a kind of virtuoso move as well, and if there’s been a more quietly beautiful page in American comics this past year, I’ve missed it. The way the bird’s dark feathers spread out against the top of the page, both emphasizing the vertical movement upwards and dynamically freezing the moment; the way the fir tree is bent slightly back to watch the departing flight, its branches twisted in delicate, eloquently pleading curves; and of course, the blank space itself, across which want and time float and reach and never meet.

You almost don’t need the rest of the book, because Anderson’s whole story is right there. Carré captures The Fir Tree’s fey clarity, the sense of a reality made unbearably vivid by its passing. The stork is more beautiful because it is indifferent and it is gone; the sea is more beautiful because it is blank and unknown; childhood innocence tugs at our heart because of the inevitability of death. Whether you’ve read this story or not, you know what’s going to happen, which is why the temptation is to just stay on this perfect page — even though the end is here, too.

Illustrated Wallace Stevens — Disillusionment of Ten O’Clock

Girl, You’ll Be a Creature Soon

This essay ran in a somewhat different form in the Chicago Reader a couple years ago. I thought I’d reprint the original version along with some more pictures here.

_______________

Ever since the breakaway success of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman in the 80s, there’s been an indigenous niche for graphic fiction about brooding guys, languid girls, melodrama, the morbidly cute, and the cutely morbid. Titles like Gloom Cookie, Courtney Crumrin and the Night Things, and anything by Jhonen Vasquez exist in a parallel, twilight world, where super-heroes withered away from anemia and the American comics industry never decided to outsource all of its female genre fiction to Japan.

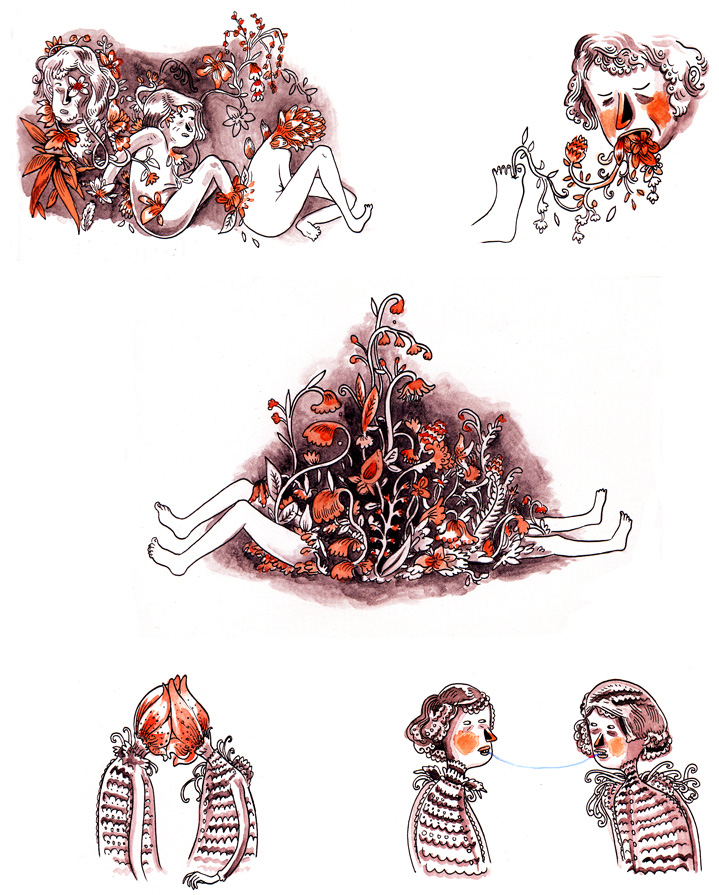

Chicagoan Lilli Carré’s debut graphic novel, Lagoon, isn’t genre fiction itself — it’s an art comic. But it’s aware of, and interested in, gothic fantasy to a degree unusual among alternative comics creators not named Dame Darcy. Indeed, Lagoonfunctions as a kind of meta-goth; an elliptical love letter to the genre and to its place in the adolescence of many young girls. The frontispiece drawing captures the affection and the distance — in a circular frame, Zoey, the tween protagonist, sits beside a lake passing flowers to a black, leaf-plastered, faceless humanoid thing. Flowers and tendrils frame the image, suggesting the overripe opulence of goth or art nouveau. But Carrés blocky linework is surprisingly sparse and even crude; it looks like something a precocious, motor-control-challenged Beardsley might have drawn when he was 6. The black monster is cute, creepy and mysterious in a very goth way, but the scene also has a sparse, modernist poignancy which is very different from tactile Victorian melodrama. Beauty is sketched out rather than embraced; the space between the girl’s hands and the monster’s is also the distance between desire and reticence, opening on a nostalgia which suffuses either the coming contact or its absence.

In fact, to the extent that Lagoon has a plot, it centers precisely around the deferral of the moment when the girl and the monster actually meet. The monster, or creature lives in an (ahem) black lagoon and sings. The girl’s family, and indeed, the whole town, is enraptured with the song; they go out to the lagoon to hear the music and dream and sometimes drown. Of all the characters in the book, only Zoey herself never, quite, sees the creature. When she goes to the lagoon, the black singing shape she finds turns out to be, not the creature, but her sleep-walking grandfather, waist deep in water. She sees the fire the creature sets in the woodpile, but not the monster itself; when she looks under her bed for monsters, it’s the wrong time and the wrong bed.

That’s because the creature doesn’t hide under Zoey’s bed, but under that of her parents. After the girl goes to sleep, her mom and dad have sex and then fall asleep. In the middle of the night, mom wakes up, opens the window, and lets the creature in. When the husband stirs, the creature slides beneath the bed, one rubbery, phallic limb poking out suggestively from under the frame.

Goth is always suffused with sexuality, of course. But what’s most creepy about this scene is not its gothic trappings — the woman in the dark, the vampiric monster at the window — but it’s mundanity. Zoey’s mother treats the creature with a banal casualness. She lights a cigarette (her husband doesn’t know she smokes) and offers to share it, then off-handedly mentions Zoey as if the monster knows her daughter well. The juxtaposition of small talk and amphibious interloper is funny, but it’s also unsettling. Vampire creepy is one thing; watching-your-mother conduct-an affair-while your-dad -sleeps-in-the -same-room creepy is something else.

Or maybe the two things aren’t so different after all. The solid blacks and blocky grotesquerie of Lagoon strongly recall Charles Burns’ Black Hole, a story in which adulthood is equated with monstrosity. In Lagoon, too, sexual maturity and horror are linked. But that link is mediated by a third term — a metaphor, a song. To be an adult is not to be a monster, but to follow one; not to be a horror, but to dream of one. Zoey, the child, is the one character in the book who doesn’t like (or who at least says she doesn’t like) the creature’s tune. Aesthetic response is sexual response; fantasy is for grown-up. Perhaps that’s why, when Zoey asks him to tell her a fairytale, Zoe’s dad is so thoroughly embarrassed —and Zoey simply falls asleep.

But if adult’s dream, the content of that dream is childhood. Sitting in the bog, listening to the creature sing, one of the townspeople comments that “A little sweetness can make you forget everything you want to forget for a little while.” But then he goes on not to forget, but to remember an incident from his boyhood. When first Zoey’s mom and then her dad sinks into the lagoon in pursuit of the creature, Carré draws a breathtaking sequence — bubbles floating through blackness, underwater fronds waving, and Zoe’s mother’s hair floating underwater. The beauty of the images and the dreamlike, wordless drift downward through the water, to the bottom, and finally to a completely black page, suggest sex, and death, and a return to the floating twilight of the womb. If the song is an initiation, it seems to lead as much backwards as forwards.

Where exactly it does lead in terms of the narrative is very difficult to say. After they sink, Zoey’s mother and father disappear from the story; we never find out what happened to them, if anything. Zoe may have dreamed the whole thing, or not. Her grandfather, though, is still there; he lies down with her and they go to sleep and a year passes. Then he cuts her hair, which, she notes with some exasperation, makes her look younger — as young as she looked a year ago, a couple of pages before.

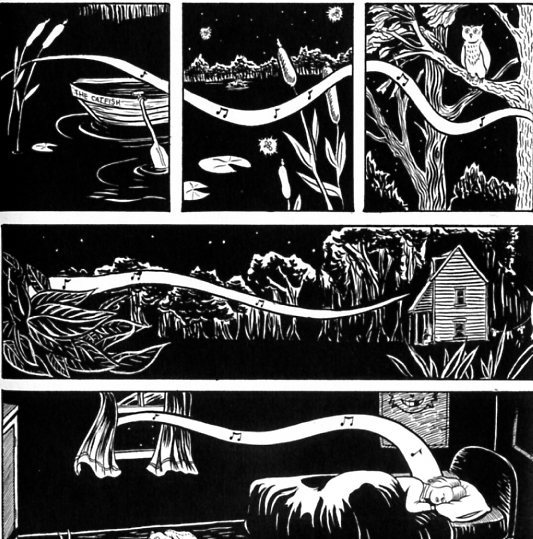

Carré binds these slippages in sequence and reality together by sound – or at least its visual representation. The click of a metronome, the squalling of cats, grandfather’s finger tapping, and most of all the creature’s song, all float through windows and across panel borders in fluid, looping ribbons, knotting together page and space and time. Childhood and adulthood are both bound or drowned in a single voice, each watching the other through a surface of dark water. Lagoon isn’t so much a coming of age as a coming and going. The girl dreams of the creature she will never see; the mother drifts downward towards a childhood that is gone. Where they meet, is, perhaps, in gothic fantasy: a girl dreams she’s a woman dreaming she’s a girl, and wakes not knowing which is which, or where the monster is.