Lone Wolf and Cub: The Assassin’s Road (Vol. 1)

Writer: Kazuo Koike

Artist: Goseki Kojima

I never read any manga as a kid. The closest I came to it was watching manga-based anime like Akira, so my impression of manga was that it was mainly about teenagers screaming at each other as they fought to the death (depending on the series, these battles might involve giant robots and/or cat-girls). And the manga digests were alien and weird, these thick, little books with black-and-white artwork.

Now I’m older and a little bit wiser, so I’ve decided to let go of my prejudices and see what all the fuss is about. But the sheer size of the manga industry, along with my total unfamiliarity with the major titles, has made it difficult to find a clear point of entry. And while I try to keep an open mind, I’m not quite ready to jump into yaoi. I’m sticking close to my comfort zone, which just so happens to include samurai.

Lone Wolf and Cub proved to be a great starting point. Set during the Tokugawa era, it depicts the adventures of the assassin Ogami Itto and his infant son Daigoro. The chapters in the first volume are episodic. Other than Itto and Daigoro, characters do not carry over from story to story. Also, each chapter tends to follow a simple formula: Itto arrives in some town or village pushing his son around in a cart, he toys with his target for a while, his target ineffectually tries to get rid of him, and Itto then kills his target and everyone who gets in his way. And occasionally, hot women remove their clothes.

Of course, there’s a downside to the episodic approach. Even having just read the volume, it’s hard to remember the specific details of any one story, and all the chapters feel vaguely indistinguishable. Like every procedural on television, enjoying Lone Wolf and Cub is contingent upon enjoying the repetition of particular themes and events. As someone who enjoys reading about samurai, I found the stories entertaining, but it’s easy to imagine someone with different tastes finding it to be a repetitive bore.

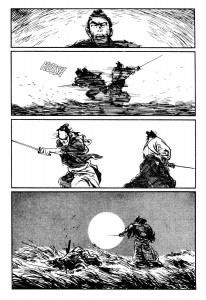

The art is actually the bigger selling point. Goseki Kojima’s style is heavily influenced by traditional Japanese artwork, and it’s absolutely perfect for the subject matter. He’s also a capable storyteller. Panels are attractive and uncluttered, spatial relationships are clear, and the panel layout ensures that the narrative is easy to follow. His talents are particularly evident during the fight scenes. Many Western comic artists have trouble creating the illusion of motion in a medium comprised of static images. Kojima is one of the few artists I’ve seen who can plot a fight scene so that actions that occur between panels are just as obvious as those depicted in the panels.

As these pages make clear, Itto is a sneaky bastard.

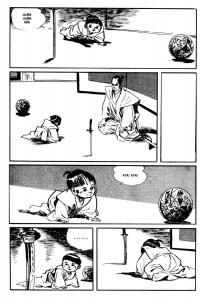

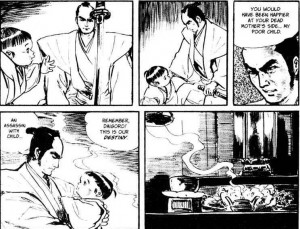

The various chapters touch upon themes that will be instantly familiar to fans of samurai stories (honor, self-sacrifice, bravery, etc.). But the most prominent theme throughout the entire volume is the devotion between father and son that survives even as Ogami Itto follows the “assassin’s road.” Itto clearly loves Daigoro, but at the same time Itto is an essentially violent man, and he chooses to work as an assassin as he plots his revenge on the men who disgraced him. His love for Daigoro is conditional on Daigoro being worthy to follow in his footsteps. In practice, this means that Itto frequently risks Daigoro’s life just as he risks his own life. The potential conflict between Itto’s profession and his love for his son never arises, however, because it’s clear from early on that Daigoro truly is his father’s son.

But for all its high-minded pretentions about honor and family devotion, Lone Wolf and Cub is overflowing with violence and sex. At first glance, the book seems to be an uneven combination of high-brow Eastern philosophy and low-brow exploitation. This is partially deliberate. Kazuo Koike no doubt intended to explore the contradiction between bushido ideals and the harsh reality of feudal Japan. But the book is also clearly nostalgic for an era when men were men. Ogami Itto is Koike’s ideal man: strong, relentless, sexually virile, and honorable in his own way (and ignoring all the times he risks his son’s life, he’s a loving father too). In Koike’s vision of feudal Japan, there is a natural coexistence of philosophy, ideals, violence, and sex because only in this era could men achieve both physical and spiritual perfection.

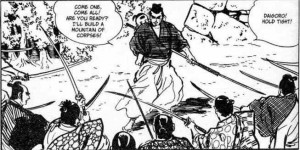

So Lone Wolf and Cub is retrogressive and occasionally quite sleazy. But I couldn’t help but enjoy it. I may be a bleeding heart, but I appreciate action stories with great art and clever plotting. Here’s my favorite panel of the entire volume:

A part of me is offended by how Itto is so unconcerned about Daigoro’s safety. But a much bigger part of me admires the badassery of killing 10 men while giving his son a piggyback ride.