I watched Love Actually recently, and was reminded yet again that in romcoms, and just in Hollywood in general, the women are almost always more attractive than the guys. There are lots of couples floating around the film, and some of them are more or less balanced in age/attractivness…but then there’s homely cute aging Hugh Grant with the blindingly hot Martine McCutcheon (who of course has to endure constant jokes about her weight) and the homely cute aging Alan Rickman at whom the much younger and exponentially hotter Heike Makatsch keeps throwing herself. The Woody Allen dynamic of dweebish guy with sizzling younger woman is a Hollywood staple (and is only made more uncomfortable by the allegations about Allen’s real-life abuse of a 7-year-old.) But the reverse — dweebish woman with sizzling guy — hardly ever happens.

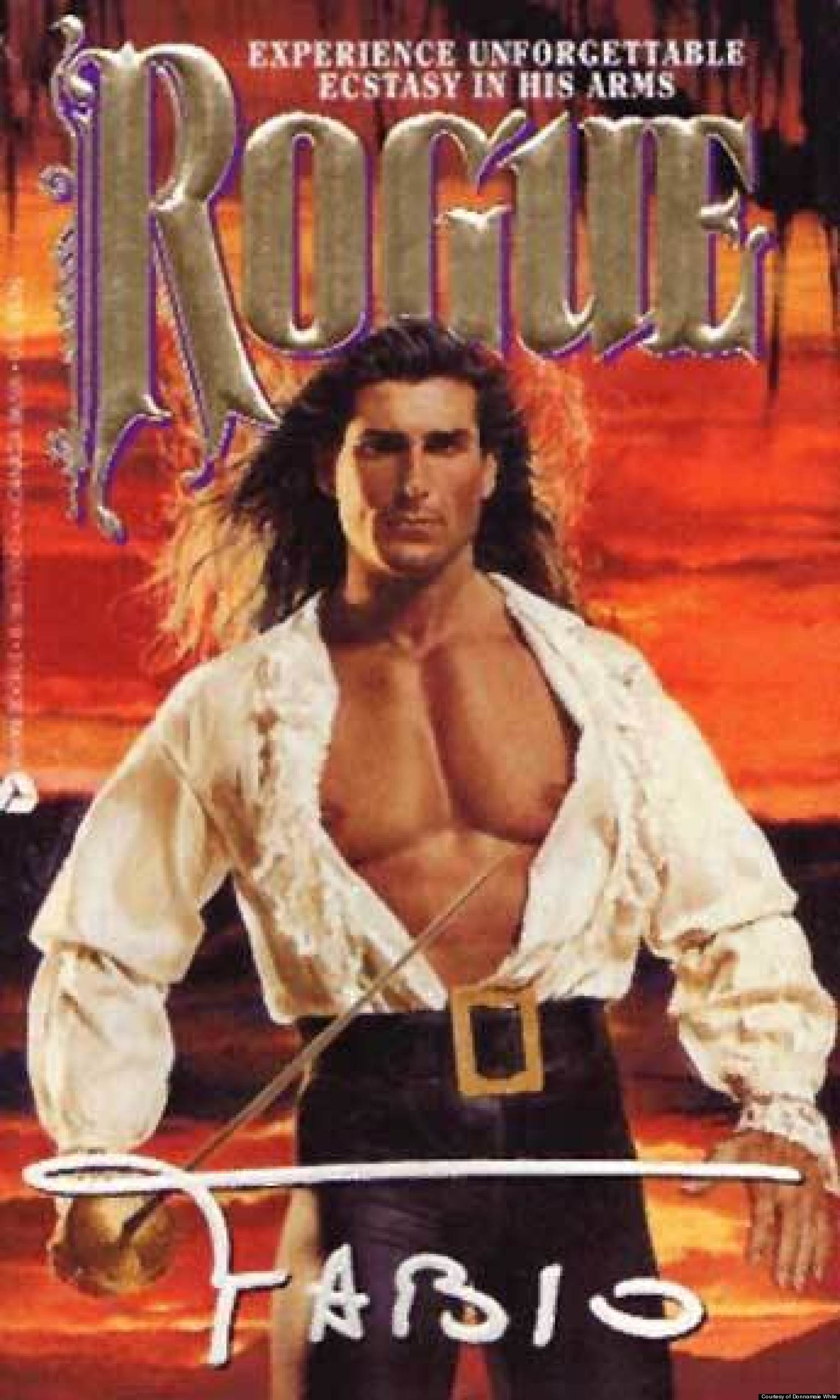

Or at least, it hardly ever happens on film. I’ve read a bunch of romance novels recently, and there the tropes are pretty consistently reversed. At least in the dozen or so books I’ve read, there is not a single instance of the character actor guy getting the incredible babe in the end. Instead, both men and women tend to be described as ravishingly attractive (and, in the case of men, as having impressive genital equipment. Size, in romance novels at least, does in fact matter.)

Or at least, it hardly ever happens on film. I’ve read a bunch of romance novels recently, and there the tropes are pretty consistently reversed. At least in the dozen or so books I’ve read, there is not a single instance of the character actor guy getting the incredible babe in the end. Instead, both men and women tend to be described as ravishingly attractive (and, in the case of men, as having impressive genital equipment. Size, in romance novels at least, does in fact matter.)

Or, if both are not ravishing, then the one who is not is, consistently, the woman. In Jennier Crusie’s “Bet Me”, the Adonis-like Cal passes over the perfect, slim, Cynthie in favor of the decidedly not-thin Min, who is described in her initial appearance as being “dressed like a nun with an MBA.” In Cecelia Grant’s “A Gentleman Undone,” the novel proper begins with the words, “Three of the courtesans were beautiful. His eye lingered, naturally, on the fourth” — that fourth being our heroine. In Judith Ivory’s “Black Silk,” the most notable physical characteristic of the protagonist is her irregular teeth — which the hero finds “Oddly” but “strongly feminine.” Here, as elsewhere, the men see past the women’s imperfections — or, indeed, the men are attracted by the imperfections.

Obviously, this particular narrative difference has to have something to do with differing demographics. Romance novels are aimed overwhelmingly at women, so you get fantasies in which normal, non-Hollywood-hot women date perfect male specimens who can see the beauty not just in their personalities, but in their deviations from tyrannical beauty standards. The only surprise is that Hollywood doesn’t tap into this pretty simple fantasy more often — an indication, perhaps, that having films directed and produced almost entirely by men does in fact have a noticeable effect on the content of even films supposedly targeted at a mixed audience (like “Love Actually”).

So (het) men prefer fantasies in which schlubby men get hot women, and (het) women prefer fantasies in which schlubby women get hot guys. That seems predictable enough. But what’s maybe a little surprising is that, in other respects, the genders’ ideal fantasy is congruent. Or at least, both Hollywood and romance fiction seem to agree that the ideal romantic pairing is one in which the guy is substantially richer and more powerful than the woman.

The magnitude of the difference here can vary a good bit. The reductio ad absurdum is Twilight, with the fabulously wealthy and superpowered vampire sweeping the simple high school student out of the prom and into eternal life. But the meme hold up to one degree or another both in “Love Actually” (where Hugh Grant gets to crush on his secretary, Alan Rickman, as noted above, is flirting with his secretary, and one of the other characters falls in love with his maid) and in the romance novels I’ve looked at. As I mentioned last week, in Jennier Crusie’s Welcome to Temptation, the heroine is a struggling filmmaker while the hero is the town mayor. In Pam Rosenthal’s “Almost a Gentleman” the hero is a cross-dressing man of fashion, but the hero is a powerful, wealthy lord with extensive property. Cecelia Grant’s guy in “A Gentleman Undone” is not rich…but her heroine is a a courtesan whose status is precarious enough that the guy seems relatively well off. Beverly Jenkins’ Indigo goes the full-bore 50 Shades route; the heroine is an ex-slave barely maintaining herself in the middle-class, while the hero, a New Orleans freeman, has apparently limitless wealth and resources.

Again, the fantasy here isn’t hard to parse; if you can marry for true love and fabulous wealth, why settle for just marrying for true love? The guy having wealth and power is also a useful narrative convenience; it’s a lot easier to have a happy ending if someone can wave his checkbook at the finale and make most of the problems disappear. Really, what’s odd is that romantic fantasies for men don’t take this practical approach as well. Why don’t all those guys making Hollywood movies ever have their homely guys fall for some woman who is not only young and beautiful, but incredibly wealthy as well?

But that’s not how it works. In their fantasies, women imagine handsome, powerful men, while, in their fantasies, guys imagine men who are powerful, if not always quite so handsome. Everybody seems to agree, though, that powerful guys are more romantic.

That agreement is an agreement to, or about, patriarchy. Men=power; power=manliness. As I suggested in my piece about Crusie’s Welcome to Temptation last week, a good part of the rush, or allure, of these het romance novels, at least, seems to be not just the love story, but the way the love story turns into a story about women becoming powerful through men; you pick up the phallus to pick up the phallus. That’s a story about women’s empowerment, certainly, but it’s also, or along with that, a story about women endorsing power as defined in pretty straightforward patriarchal ways. Romance is good at giving women what they want. But to the extent that what they want is both men and power, it seems to have trouble in not conflating the two.