(with apologies to Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart)

Luke Pearson’s Hilda series seems to have fallen into that strange fault line lying between comics elitism and wide commercial acceptance. The comics series’ wholesome embrace by the mainstream press seems to have been met by a less than commensurate response by comics critics in particular; this despite an Eisner award and the occasional short but glowing review by the specialty press.

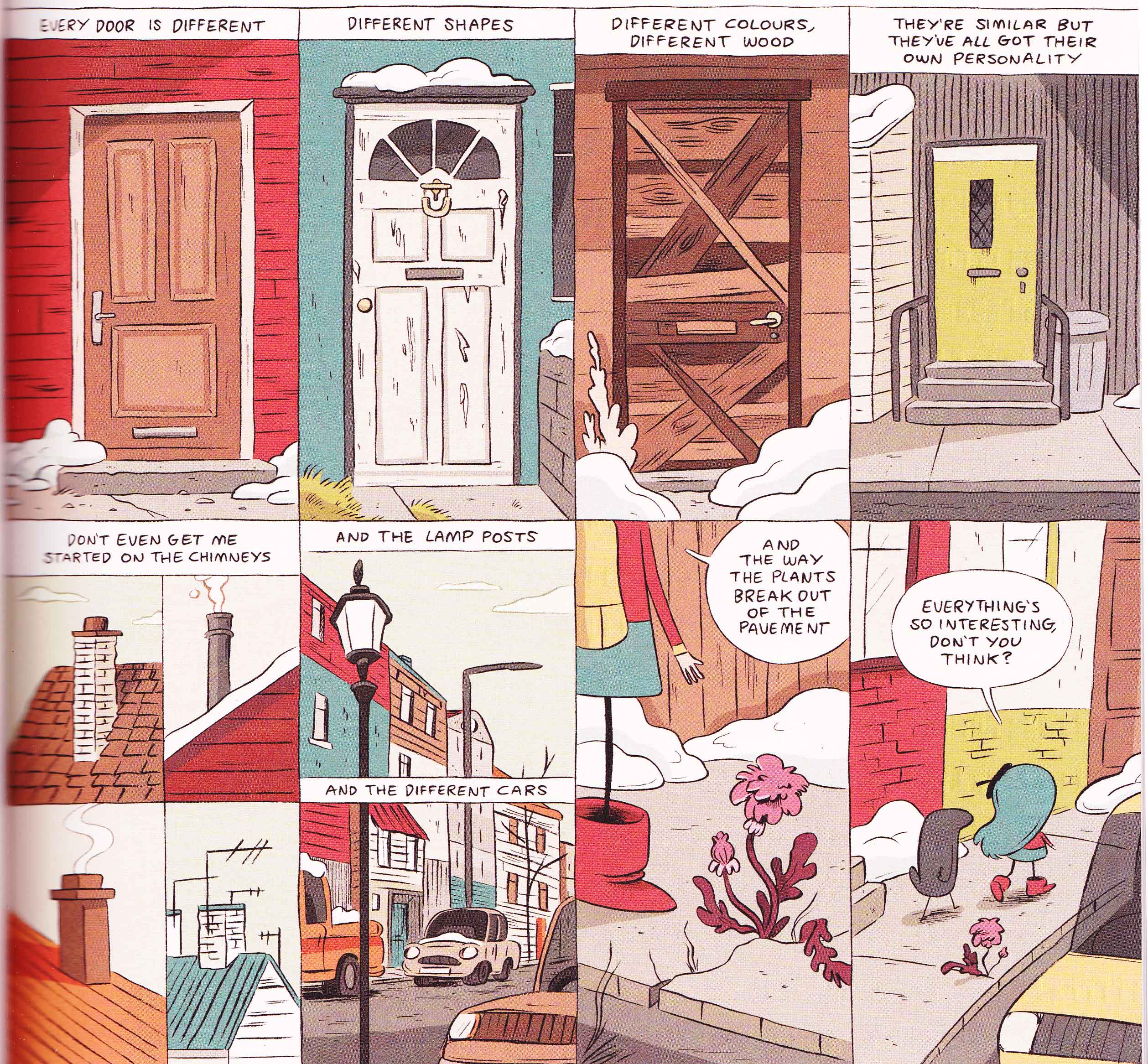

The attractions of the Hilda series are quite easily surmised. There is the clever knitting together of various northern European traditions, the artist’s increasing competency with page composition, his good ear for simple but humorous dialogue, his pleasing character designs, and his consistent and attractive line which has achieved a fine flowering in The Bird Parade and The Black Hound.

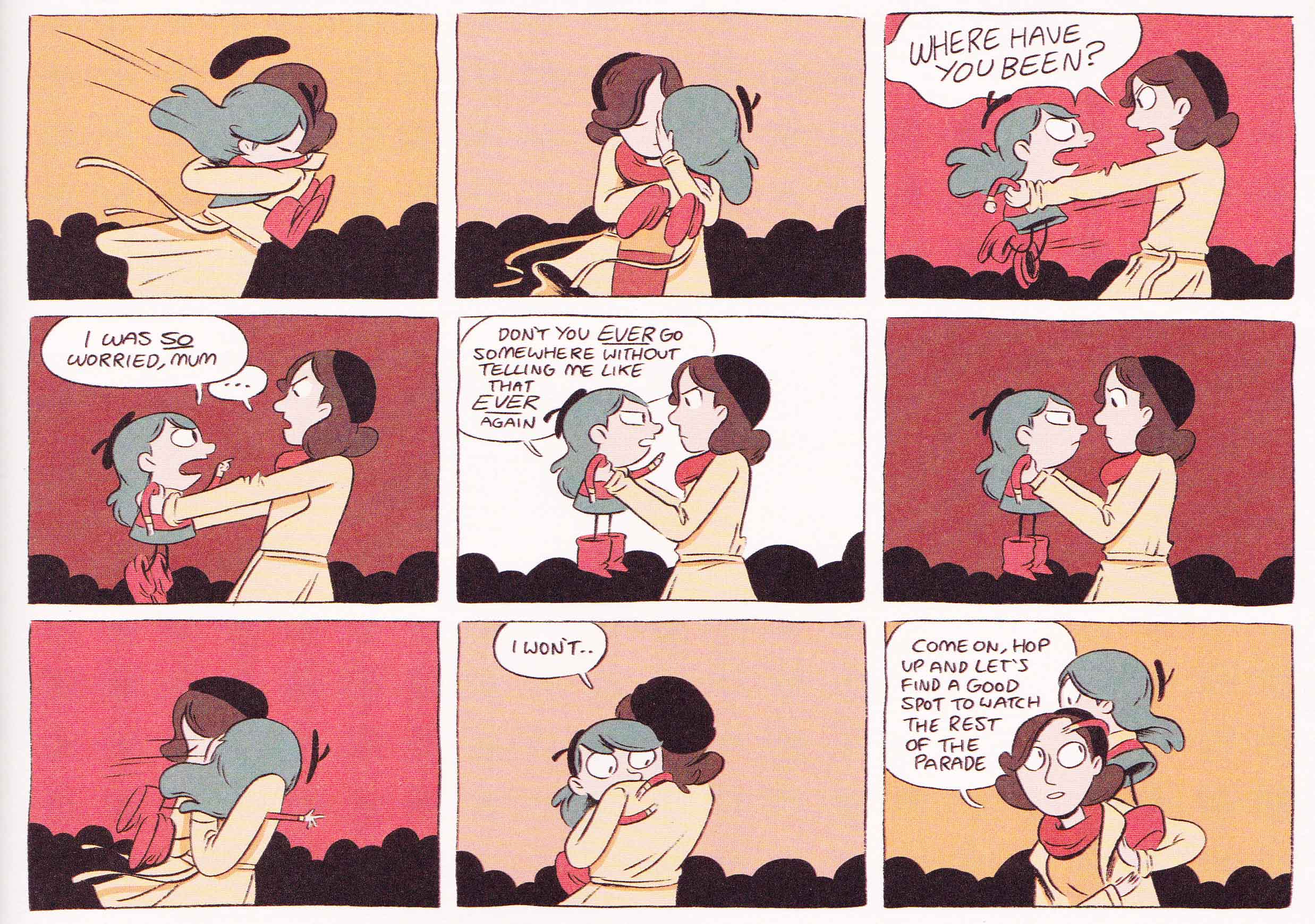

Reviewers have found it useful to compare Pearson’s work to that of Tove Jansson, Jonathan Swift (with regards Hilda and the Midnight Giant) and, more often, Hayao Miyazaki. This is understandable considering the independence and confidence of his heroine, her love of nature, her devoted pet (Twig), and her navigation of a mythical Nordic landscape (which might be compared with Miyazaki’s work on Spirited Away). One presumes that the series also owes some debt to the work of Bill Watterson in its formation of an all-consuming world of uninhibited fantasy, as well as the central relationship between parent and child (though I feel it is no accident that Hilda is being brought up by a single parent). Hobbes in Pearson’s creation is a series of not so imaginary friends crawling out of the wood work. In fact, at one point, Hilda is shown to be delighted at the possibility that the invisible voice in her head could be an imaginary friend (it is actually an elf).

Suggestions that Pearson’s series has nothing to offer adults should not be entirely glossed over. There is every reason to believe that the classics of children literature offer something tangible to adults reading them (written as they are by grown ups); even if we might be tempted to think this an illusion brought on by melancholic nostalgia. As with many children’s books, there is an overarching sense of morality in Pearson’s comics, sometimes overt but frequently more subtle and veiled. The former instance can be seen in various passages from Hilda and The Bird Parade where Hilda consistently resists pressure from her peers to commit acts of nuisance and finally of violence. There is also a gentle study of prejudice in the form of Hilda’s friend, the Wood Man, who is greeted initially with indignation at his domestic intrusions until he helps her find her way back home when she is lost in a deep forest.

Pearson’s more clandestine evocations can be most clearly seen in the second book in the series, Hilda and The Midnight Giant.

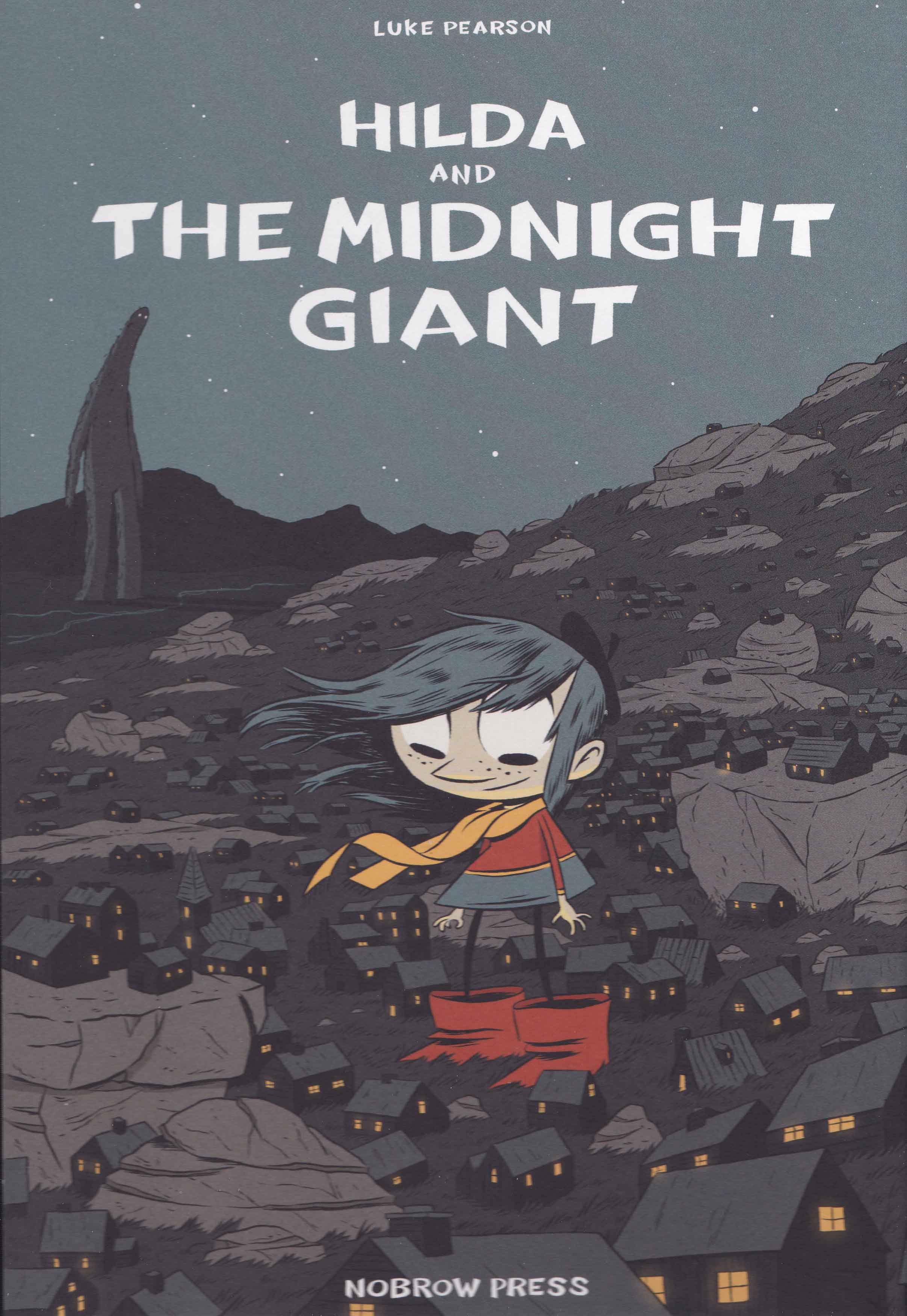

The cover to The Midnight Giant is clearly a reference to Goya’s (or Asensio Julia’s depending on your point of view) The Colossus.

Goya’s work has been appropriated by various cartoonists over the years; sometimes in the service of frank homage—as has been the case with Mike Mignola—and in other instances for reasons somewhat antithetical to Goya’s own politics—as has been the case with Attack on Titan. The exact nature of the giant in Goya’s painting is ambiguous and there have been arguments positioning it as a figure of tyranny, a protector, or a mysterious force.

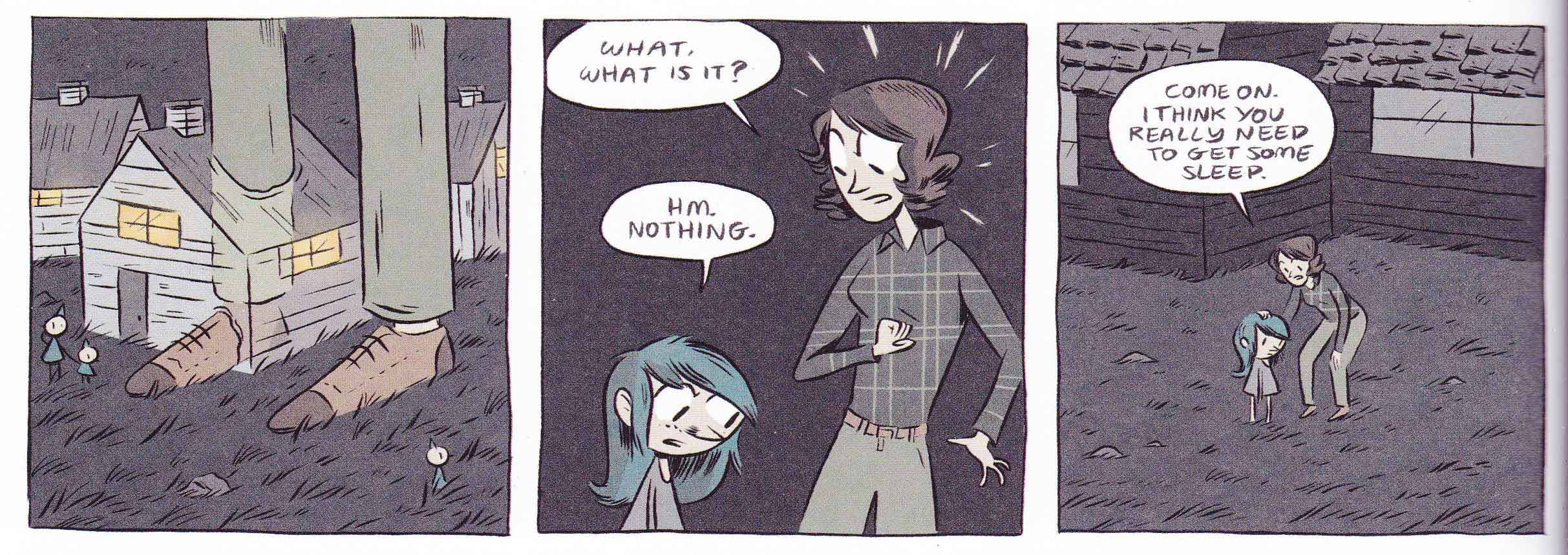

In The Midnight Giant, Hilda and her mother suddenly come under attack by invisible foes throwing stones through their windows; these acts culminating in an attempt at forced eviction by these minute malcontents. The attack is largely ineffectual and the perpetrators are swiftly chased away with a broom.

Only when Hilda (with the help of an elven sympathiser) signs a large sheaf of papers representing a kind of legal authorization can she finally be allowed to see the entire Elven civilization upon which her home has been built. In tiny Kafkaesque vignettes, Hilda works her way up the chain of command from the town mayor, to the Prime Minister and finally to the Elf King—all of whom repeat the same mantra of lacking hands (literally) to change things and their being “lots of forms” signed in the discharge of this silent war. Summarized in this manner, Pearson’s intentions would appear both bald and facile. In reality they are buried beneath a surface which exudes color, European tradition, adventure, and a comfortably large world of the imagination. Any sense of oppression or linkage between invisibility and intellectual blindness is barely hinted at.

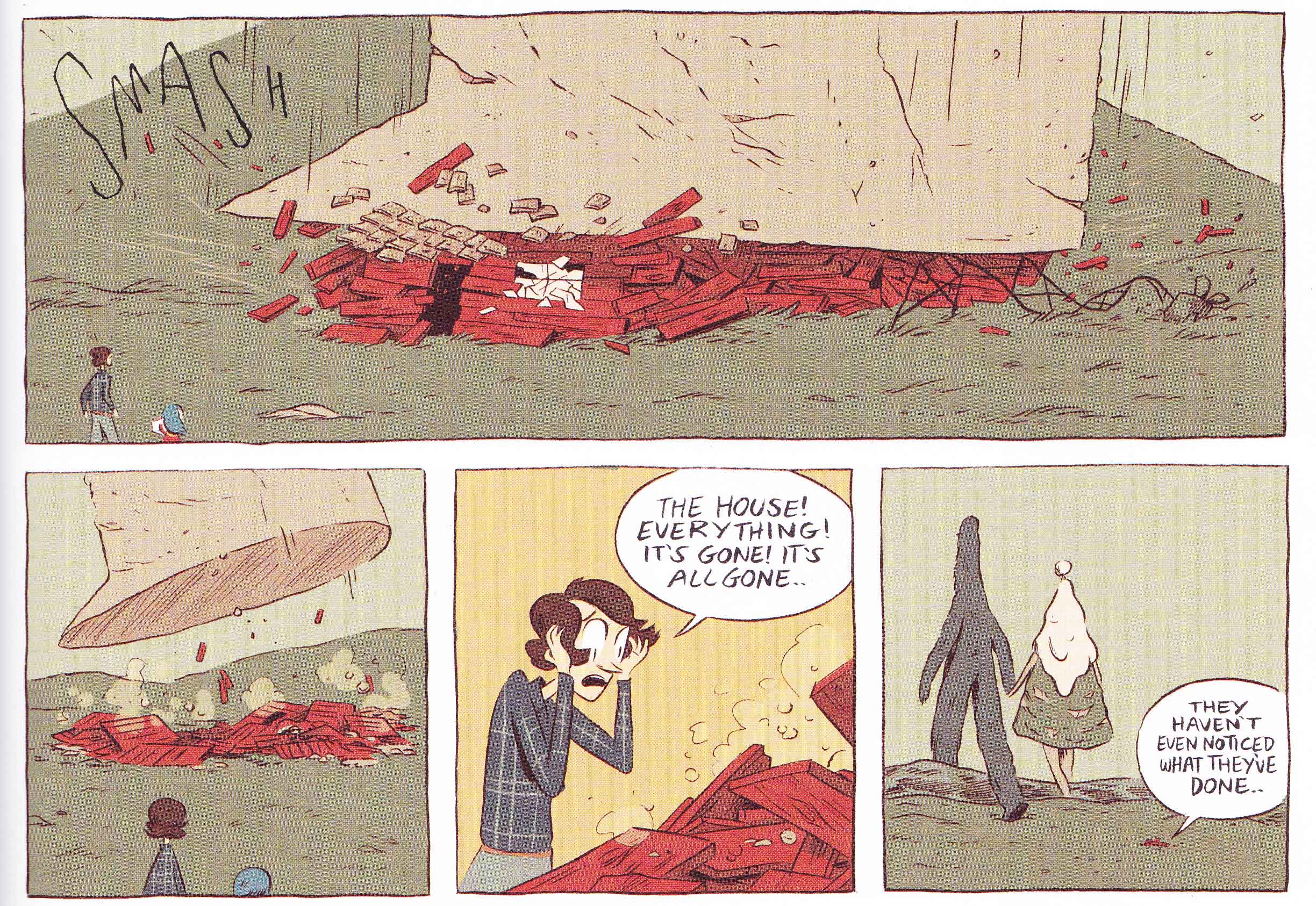

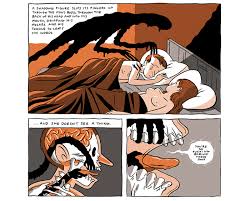

Part of the trick of writing and drawing a children’s comic is that balance between charm and terror. The tone of the Hilda series is such that we feel confident that Hilda and those closest to her will never be in any real danger. Yet there remain moments of contained sadness as when the elven communities predicament is brought home to Hilda and her mother on the penultimate page of The Midnight Giant.

“They haven’t even noticed what they’ve done…”

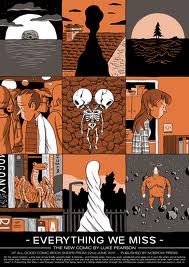

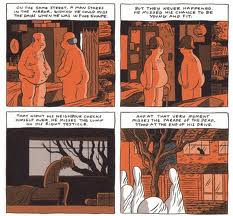

If there are any concerns about the subjugation of the weak or even the amnesiac qualities of our basic histories (the editor of this site likes to mention James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me), then these are made flesh when the gentle giants step on Hilda’s house and nearly kill her mother. These unseen calamities also form the basis of Pearson’s Everything We Miss (a more adult-oriented work).

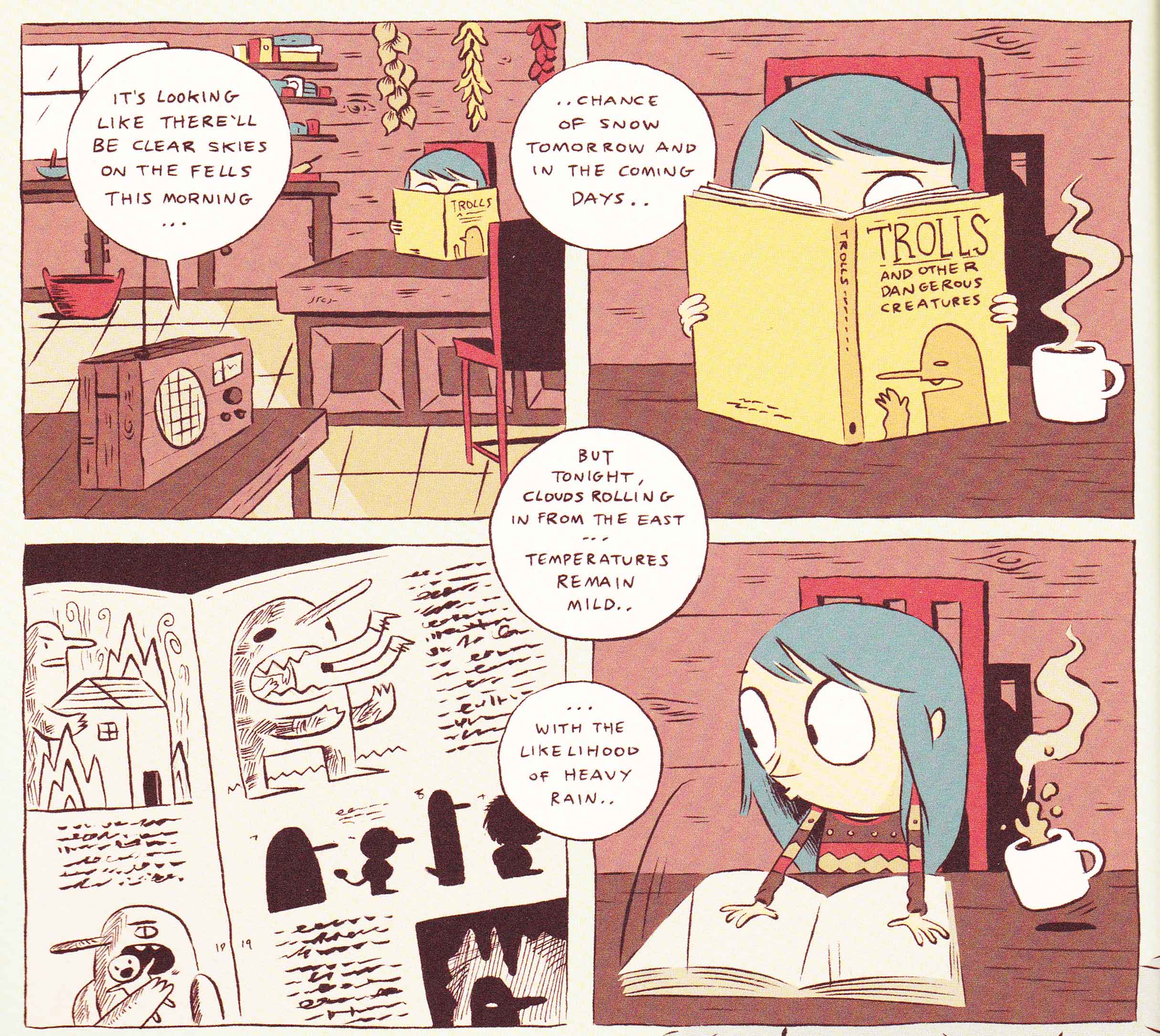

Hilda’s inability to see at the start of The Midnight Giant is part of a more extensive meditation on knowledge and perception in Pearson’s comics. Hilda’s next adventure finds her in Trolberg which has been built in the middle of trollish lands with bell towers built at strategic points in order to dissuade violent incursions by trolls. These trolls —a wide-mouthed monstrosity in the tradition of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son—have a notorious reputation for eating humans but are also described as being rather peaceable in book 1 of Hilda (Hildafolk, since retitled Hilda and the Troll).

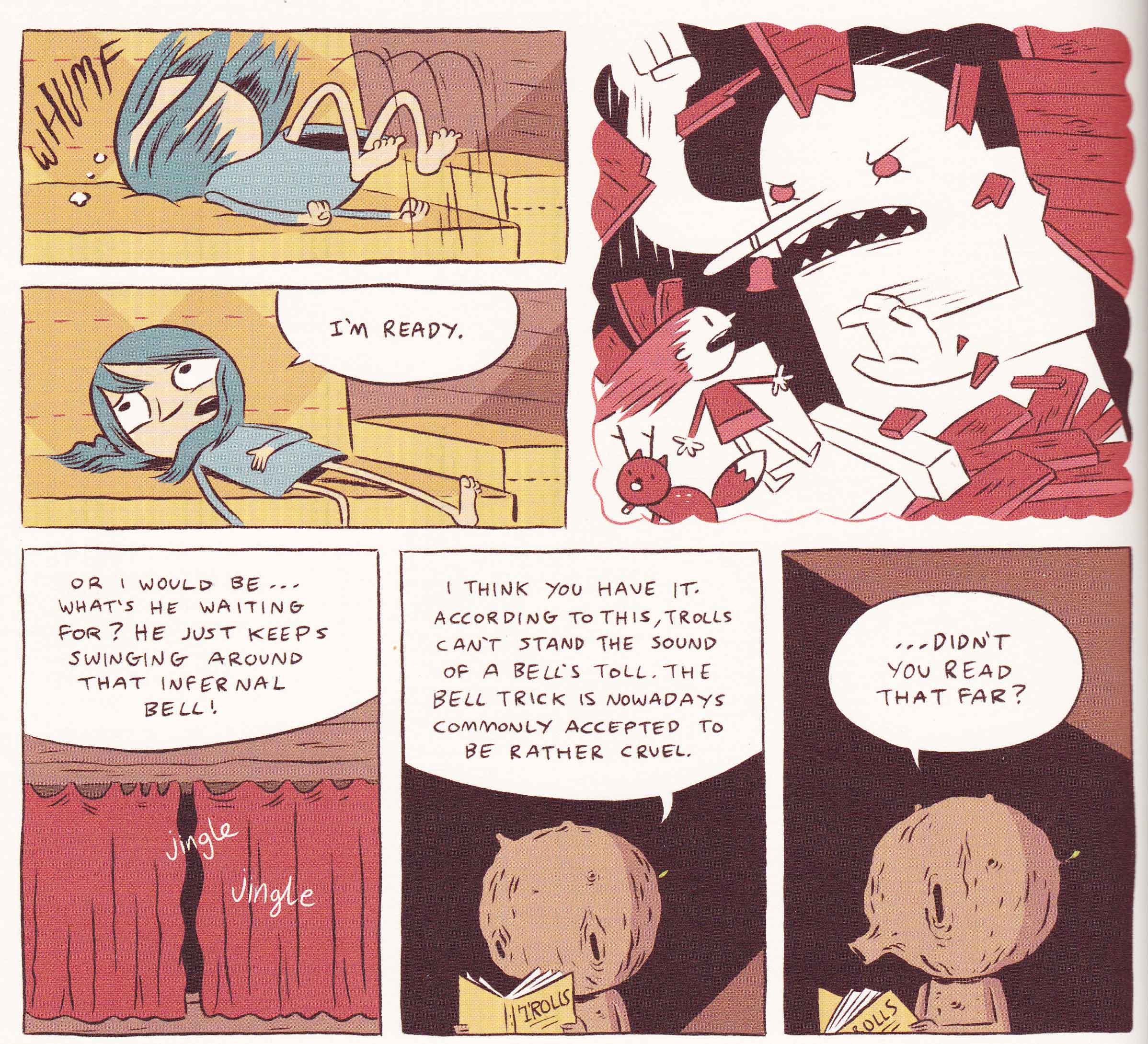

This leads us to another one of the underlying questions in the Hilda series—the tension between the knowledge and experience of others (as captured in the first book we see Hilda reading, “Trolls and other dangerous creature”) and our own perceptions of reality. I suppose one could also see in this the relationship between hermeneutics and empiricism. In Pearson’s first book, Hilda is convinced of the danger posed by trolls and bells a troll rock which she wants to draw. Much like belling a cat, she expects to be alerted if and when the troll rock stirs to life. As it happens, she falls asleep and wakens to find that the troll rock has disappeared. That night she is woken by the “jingle” of the belled troll who she imagines has come for some form of retribution. Her friend, the wood man, on reading her guide to trolls informs her that the practice of belling is now “commonly accepted to be rather cruel” and that she should “always read the whole book.”

Hilda doesn’t really have the time for this of course. After all, there’s some concern that she’s about to be eaten by a troll—a concern which proves to be totally unfounded since the troll not only leaves her alone but returns her sketch book to her. The guide book has been useful in revealing her mistake but is eventually found to be somewhat faulty (at least in this instance) with regards to the nature of trolls. Hilda encounters a similar situation in Hilda and The Black Hound where cursory knowledge and the fear of otherness lead inevitably to the wrong conclusions concerning the existential threat facing Trolberg (as well as more forced evictions). There is everywhere the suspicion of single points of knowledge and second hand paranoia. One might also wonder why the first inhabitants of Trolberg decided to name the city after their infamous enemies (apart from its descriptive utility of course). I presume for the same but varied reasons the first European settlers decided to name their cities in deference to the languages used by the first Americans.

I should note here that this focus on ignorance, invisibility and careless destruction is so light that the interviewer at Der Tagesspiegel crouches his question concerning the relevance of The Midnight Giant to the situation in modern day Israel with another question concerning “over-interpretation.”

Pearson’s concerns are naturally much greater than this single issue but point to every instance where ignorance creates chaos and ghostly eradication (see for example the way in which Hilda and her mother step through the Elvish town without damage when they are ignorant of its existence).

In so doing, Pearson carves out even more questions concerning the nature of good and evil. For instance, are the actions of Hilda and the giants excused because of their ignorance and obliviousness to those around them, or is there more to our moral calculus then mere intention?

This fascination with the ambiguity of life is carried over to other aspects of the series. Pearson is perhaps most pointed on this issue in Hilda and the Bird Parade. The parade in question has been formed to celebrate the arrival of a big raven seen to be an earthly manifestations of one of the ravens know to sit astride the shoulders of the Odin-like god whose statue lies at the center of Trolberg. The raven makes clear to Hilda that its arrival (or failure to arrive) has no effect whatsoever on the town’s harvests, but that is not what the townsfolk believe. Yet like a priest suffering the superstitions of his parish, the raven has been returning faithfully to the town each year in order to allay their fears. A perfectly fine message for a world supposedly grown tired of the irrational, but a somewhat paradoxical conclusion to reach in a world filled with elves, giants and a raven which can change its size at will. The raven, in fact, finally reveals that it is a thunderbird which hardly seems a great argument against the supernatural.

All this would seem to suggest a world weighed down with uncertainty, conflict and cares; hardly ideal reading material for under 10s. Yet as virtually every review of this series will attest, this is almost never the case. Hilda may make mistakes but she is never cynical; her universe is large and filled with hidden wonder and mystery.

…her family ties are uncorrupted and enduring, the wilderness occasionally frightening but kind. The world we live in can sometimes appear loathsome and hideous, but once we were children.

___________

Further Reading

Chris Mautner interviews Luke Pearson:

Pearson: “I wanted a character who was very positive and who would get caught up in adventures as a result of her own curiosity, empathy or sense of responsibility. The kind of character who has an adventure because she really wants to, not because she’s forced into it…I knew she should be interested in everything and constantly questioning the things that happen to her…The only firm “don’t” I gave myself is that she should be non-violent and that she never resolves anything with a fight.”

“Mautner: Many of the Hilda books thus far, especially the new one, involve creatures and characters that seem menacing or meddlesome at first but turn out to be harmless or beneficial. I was wondering how conscious you were of this theme and how it ties into your desire to have Hilda avoid violence.

Pearson: I’m very conscious of it and worry about how quickly that could (has?) become trite…It’s definitely connected to avoiding violence but also to avoiding antagonists in general…I’m not against depicting violence or anything and it does occur to some extent…I tried to show that the Hound is dangerous; it’s not a misunderstanding or anything. I’m inclined to finish each book on a positive note because they’re standalone stories and everything needs to be resolved in some way. I just don’t want the resolution to ever be Hilda bashing some evil creature’s head in and for that to save the day.”