Earlier this year I was asked to lead a workshop on comic books for 4th and 5th graders. I had organized activities like this for kids in the past, but never for a group quite this young. So I trimmed a few points in my presentation notes about comics history and highlighted examples of how the art form is used to tell different kinds of stories. I simplified the drawing exercises and group activities in order to encourage the students to make comics of their own.

While I was preparing for the workshop, news broke that that South Carolina House Ways and Means Committee had approved budget cuts against the College of Charleston that would effectively penalize the school for assigning Alison Bechdel’s comics memoir, Fun Home, for their freshman reading program. The state representative that proposed the bill claimed that the comic’s depiction of homosexuality “could be considered pornography” and that the college’s selection was tantamount to “pushing a social agenda.” Shocked and outraged by this move, I complained to friends and colleagues. But I also looked again at the packet of course materials I had prepared for the elementary school students in my comics workshop. Along with a new Adventure Time comic, I had included excerpts from Krazy Kat, Astonishing X-Men, American Splendor and a short comic by Lynda Barry. It was this last one that began to worry me.

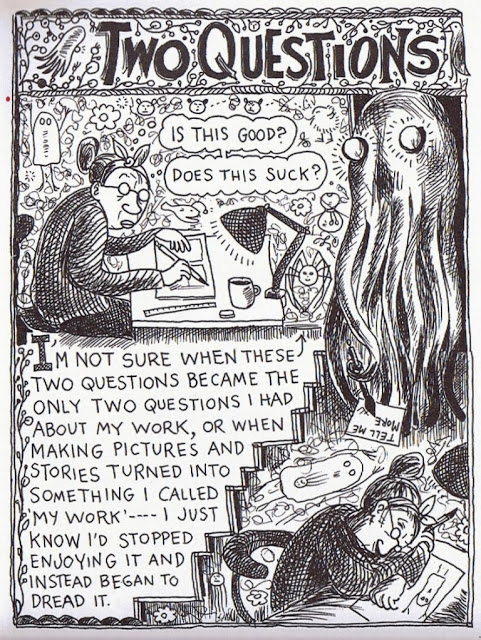

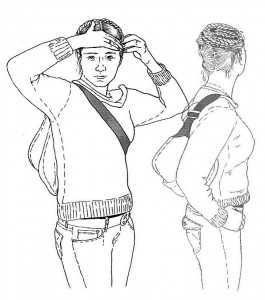

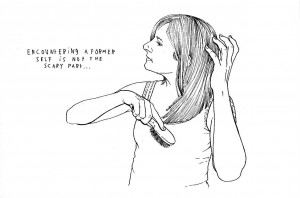

Barry reflects upon the self-doubt and judgment that can paralyze creative expression in “Two Questions” from her 2008 collection, What It Is. She recalls the playfulness and experimental energy of her own childhood drawings, drained by the onslaught of those two questions: “Is this good?” and “Does this suck?” The doodles, vines, and swirls of text that surround Barry in the four-page comic make her internal conflict visible in a way that beautifully illustrates the interplay of the word and image. But reading it again, I became concerned about how the vernacular phrase “Does this suck?” would be received. I worried, too, about the moment when Barry’s describes the monstrous manifestation of her insecurity as a pimp that says, “I don’t steal nothing from the girl except her mind!” Would I be prepared to address these references and if asked, to explain the sexual connotations that shaped their meaning? What might their parents think? Or the South Carolina state legislature? Would I allow my own kids to read this comic?

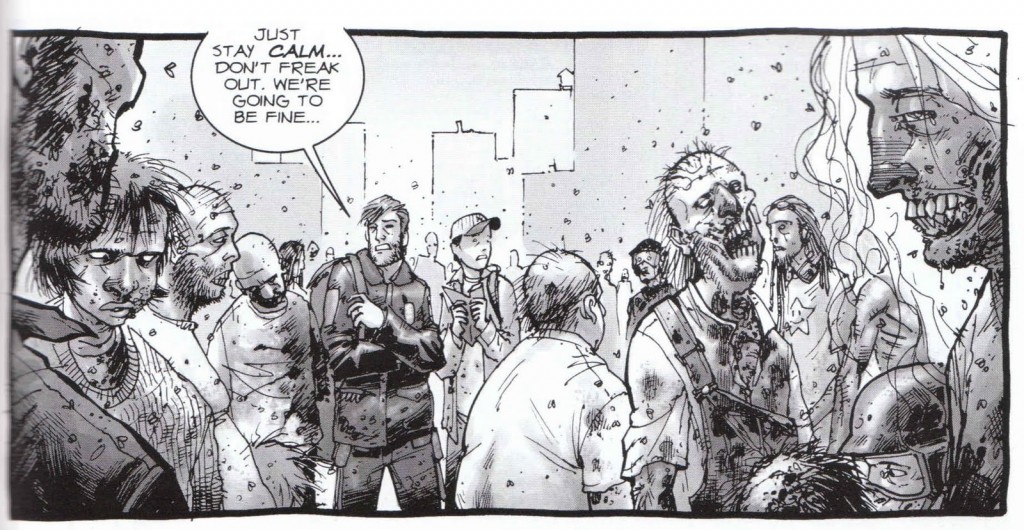

As it turned out, the workshop was incredibly successful. The kids were enthusiastic and full of ideas, excited mostly about superhero comics and anime, but open to learning about other genres too. During the first break one started talking about The Walking Dead. Other kids sat up in their chairs and nodded in agreement. I was stunned by how many knew (or claimed to know) the comic and the TV series. Soon they were reeling off their favorite characters in comics. Deadpool was a huge hit, along with the Dark Knight (the movie). A couple had read Watchmen. But some of these comics are incredibly violent, I teased – do your parents know you’re reading this? The students nodded and shrugged, although there were a few guilty smiles.

By the end of our day together, it became clear to me that these 4th and 5th graders had been handling more mature material than I could have ever imagined. They negotiated the complexities of the page impressively too. We had fun playing around with interpretations of aesthetic and formal elements in our readings of comics. I realized that Barry’s “Two Questions” would not be too much of a challenge for this group — that is, if I had let them read it. I had taken the story out of the course packet at the last minute and told myself that I would find something better. I never did.

Comics and graphic novels are the focus of this year’s Banned Books Week, an initiative supported by organizations such as the American Library Association and Comic Book Legal Defense Fund to celebrate the freedom to read by calling attention to titles that are being challenged in schools and libraries across the country. That Jeff Smith’s Bone, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Craig Thompson’s Blankets, and other comics by Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Frank Miller, and Howard Cruse have been targeted may come as little surprise to comic book readers and critics. Often the issue of age-appropriateness is the central question for the complaints against the violence, sexuality, or cultural conflict depicted in these titles. I’ve had the opportunity to teach many of the comics that have been challenged over the years in my university classes where I try to approach controversial material as a source for an enriching exchange of ideas and to consider how discomfort can enable deeper inquiry into the world we all share.

But when I had the chance to put these ideals into action with a younger audience through “Two Questions,” I made a different, safer choice. It felt all too complicated, especially since I was dealing with elementary school students and their parents in a volatile political moment. I didn’t want to invite unnecessary scrutiny or cause problems for the program director that asked me to teach the workshop. My excuses all sounded reasonable at the time. The proposal to defund the College of Charleston’s first year reading program did not succeed in its original form, but I had reacted as if it had. Now I feel more than ever that I cheated the students by censoring my own reading list. Does this suck? Yes. Yes, it does.

The horrible irony about all this is that creative freedom is exactly what Barry’s comic is about. Her images speak directly to the risks we don’t take and the limits we place on ourselves out of fear. Ultimately the comic celebrates the courage to make mistakes, to create even when you don’t have answers to the two questions at the ready: “To be able to stand not knowing long enough to let something alive take shape! Without the two questions so much is possible.” It would have been a terrific lesson for those kids, but now I guess it’s turned into a different kind of learning experience for me.

So in honor of Banned Books Week, I’m asking about your encounters with banned or challenged comics. Are there controversial comics that you have chosen not to read or share with others? If you’re an instructor, how do you assess the risks and rewards of using this material in the classroom? How do your students respond? And while you’re thinking: read Lynda Barry’s “Two Questions” here.