It took almost a half century, but Fox and Warner Bros. finally put aside their film rivalry to co-release Batman: The Complete Television Series last month. It makes me want to drag my parents back together and sit them down on my living room couch to watch.

I had no idea why they were laughing the first time we watched the show together. It seemed like a pretty serious situation to me: Batman facing down that dastardly cowboy villain “Shame.” They were sitting with me on the couch in the den, enjoying the apparently hilarious subtleties of Adam West’s superheroic performance. If I can trust the episode guide I skimmed online, this is February 1968. Which puts me a little under the age of two. So maybe we were watching a rerun?

Whatever my extremely prepubescent age, I’m sure I had zero idea what Eartha Kit was doing in that slinky Catwoman costume. Nowadays I squirm just hearing the late Ms. Kit’s “Santa Baby” rasping from my favorite Christmas mix. I assume Julie Newmar’s Catwoman was equally incomprehensible. No smoldering voice, but the same cartoon-tight faux leather.

I don’t know when a kid’s sexuality kicks in (“When did you first suspect your might be straight?”), but I must have had a thing for good girls early on. Because Batgirl I noticed. Yvonne Craig in costume still produces an impressive Google search.

I sat through an entire episode of That Girl waiting for Marlo Thomas to open that secret compartment in her apartment wall and motorcycle out of the alley with her cape fluttering (I swore my mother had said the show was Bat Girl). But when Ms. Craig appeared on Star Trek as a green-skinned seductress who lap dances for Spock and lures Kirk onto a dimly lit bed, nothing in me recognized her. Apparently my pre-pre-adolescent id didn’t go for scantily clad She-Hulk types.

“Spidey,” PBS’ mute Spider-Man mutation, premiered on The Electric Company when I was seven. I was too busy blinking at my first full TV crush to take notice of him. I’m relieved to report no nostalgic reactions to The Electric Company cast portraits I just scrolled through. I can’t even figure out which actress arrested my attention. Rita Moreno is my best guess. According to her online bio though, she would have been around forty at the time. I’m even more surprised looking back at the shows advertising slogan:

“We’re going to turn you on!”

This may also be the year I started first grade, the year of my first crush on a non-TV entity. Her name was Marisa Moesta. Not quite as snappy as Lois Lane, but I understood the allure of comic book alliteration from an early age. I can’t picture Ms. Moesta, just the pink poodle key ring she gave me after I’d given her my own trinket of affection—what I can’t remember. But I carried her poodle in my utility belt for years. Though not, thankfully, to the Batcave of my current home.

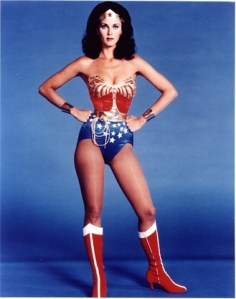

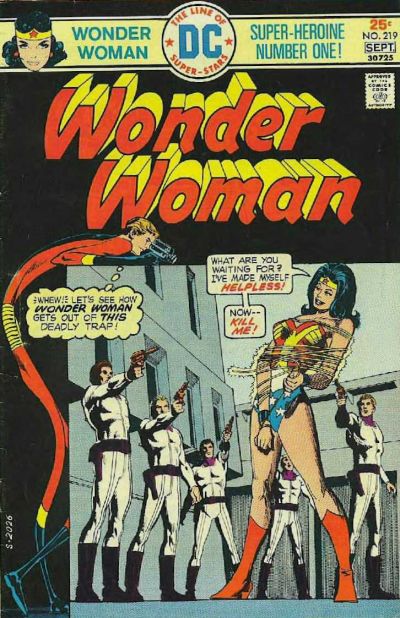

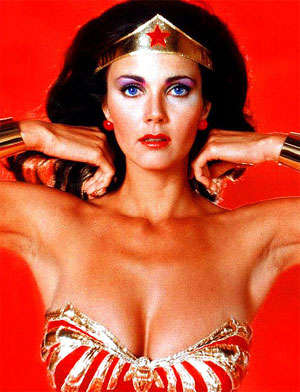

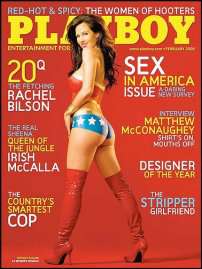

Wonder Woman premiered next, with Lynda Carter “In your satin tights / Fighting for your rights.” I had less interest in her underoos than my own. Ditto for Isis. Even I knew they’d only made her up to give the Shazam! Hour‘s Captain Marvel a girlfriend.

My wife remembers Electra Woman and Dyna Girl, a female spin on the old Batman and Robin gag. I must have been too lazy to stand up and channel surf. Which is just as well since Dyna looks like she might have been my type. Those brunette ponytails. Electra’s Farah Fawcett curls still horrify.

I’m sure I was continuing to miss subtleties, but my parents weren’t beside me on the couch anymore. When I set my smiley face alarm for cartoons one Saturday morning (Batman and Robin had recently guest starred on Scooby-Do), my mother was sleeping on the fold-out mattress in the den. I don’t know when they told my sister and me they were divorcing, but it was on that couch, the TV off for a change.

When Batgirl and Robin showed up on a 30-second public-service announcement, it was some other guy in the Batman costume. Adam West was gone, desperate to escape his Caped Crusader’s shadow, a mission he would never complete. If Batman hadn’t been cancelled back in 1968, ABC would have broken up the Dynamic Duo anyway. Robin was to be replaced by Yvonne Craig’s more popular Batgirl. But bad ratings killed them all.

Congress had passed the Federal Equal Pay Act a decade earlier, but employers were still ignoring it. I don’t know if that included the University of Pittsburgh. After moving out, my mother got a job as an assistant in one of their research labs. My sister and I helped her feed rats on weekends. It couldn’t have been much above minimum wage. I doubt Batman: The Complete Television Series includes the PSA, but I remember every second:

Batman and Robin are tied to a warehouse pillar.

NARRATOR: A ticking bomb means trouble for Batman and Robin.

Batgirl swings through a window.

ROBIN: Holy breaking and entering, it’s Batgirl!

BATMAN: Quick, Batgirl, untie us before it’s too late.

BATGIRL: It’s already too late. I’ve worked for you for a long time, and I’m paid less than Robin.

Robin sneers.

BATGIRL: Same job, same employer means same pay for men and women.

BATMAN: No time for jokes, Batgirl.

BATGIRL: It’s no joke. It’s the Federal Equal Pay law.

ROBIN: Holy act of Congress!

Batgirl moves the minute hand forward on the ticking bomb.

BATGIRL (voice over): If you’re not getting equal pay, then contact the Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of Labor.

At least Yvonne Craig and Robin actor Burt Ward were paid the same for the commercial: $0. The PSA started airing in 1973, when Craig was thirty-six. My mother was thirty-four. Craig’s final appearance as Batgirl also marked the end of her acting career. When she couldn’t get parts, she moved on to producing and then real estate.

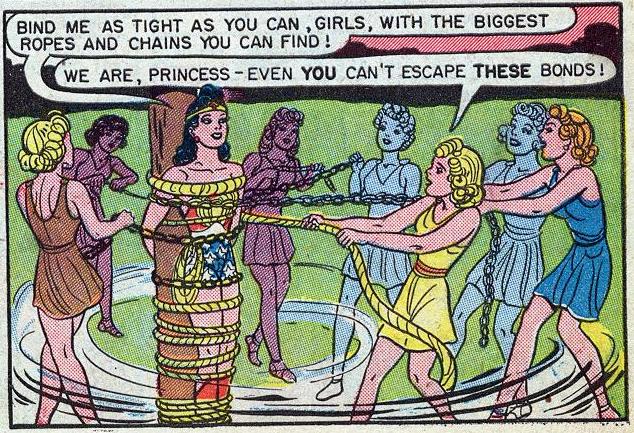

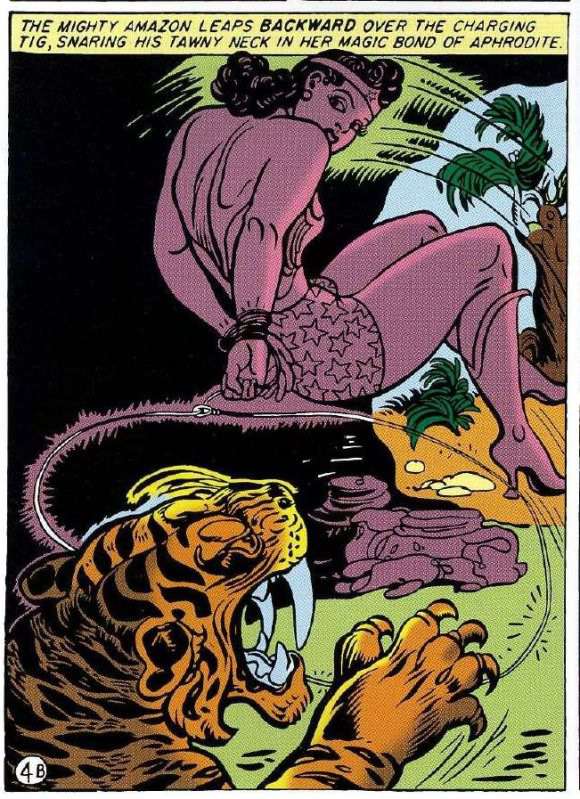

Lynda Carter held on to her magic lasso for four seasons, but it didn’t matter. The joke was over. The Incredible Hulk was the new, angsty breed of superhero. No camp, no gratuitous display of women in swimsuits and bodystockings, just the brooding Bill Bixby wandering away alone once a week. By the time The Greatest American Hero premiered, I’d already turned off the TV.