Sometime in the early 1990s, a troubled New Jersey teenager named David Klasfeld began to experiment with makeup. The hobby brought some solace into a difficult life; he was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder at fourteen. “I had 42 shampoos and conditioners because I could never use the same ones twice in a week, so I could go six weeks without using the same combination,” he said in 2013, in a New York Times piece on the company he founded: Obsessive Compulsive Cosmetics.

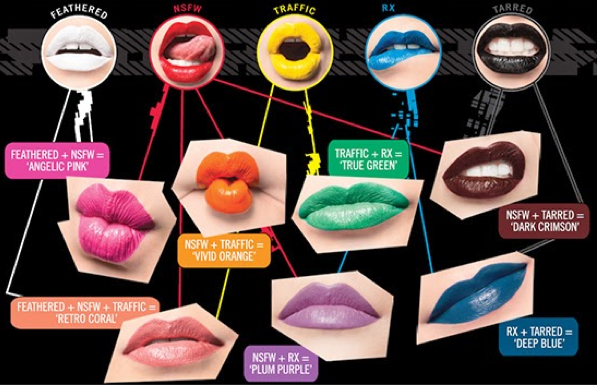

OCC is a mid-range line, more expensive than drugstore brands like Revlon and more affordable than cosmetics lines from couture brands such as Chanel and Dior. Their signature product is Lip Tar, a liquid lipstick packaged in paint-like tubes which boasts brilliant pigmentation, exceptional wear and a rainbow of shades beyond the traditional pink and red. They’re hugely popular among professional makeup artists and beauty bloggers. There’s more to celebrate about the company: their stance against animal testing is the strongest in US cosmetics, and in 2013 they helped a trans woman who worked at their boutique pay for surgery her insurance company refused to cover.

The name, though.

I probably inherited my OCD from my father. He became a hand-washer at about the same age David Klasfeld started collecting haircare products. Later in life my dad would drive around in circles, looking for bodies in the road, because he was convinced that some minor violation of traffic etiquette he’d committed had caused a chain reaction behind him, resulting in wrecked cars and mangled pedestrians. Anxiety had killed his mother, years before I was born: she was obsessed with the notion that she might become pregnant again, which so terrified her that she was going to multiple doctors to get multiple birth control prescriptions. This was in the early years of the Pill, when the drugs were stronger and the risks less well understood, and she was a middle-aged woman with high blood pressure and heart disease.

An OCD episode starts with “what if?” A thought comes into my head that frightens me. It’s almost never based in reality, but I can’t brush it off. Suddenly I can’t think of anything else. My heart hammers; my guts churn; sweat runs down the back of my neck. I try to use logic to prove to myself that the imaginary scenario won’t come true, but that only makes it worse. There’s no thinking my way out of this situation; I just have to wait until the chemicals in my brain change. I mostly don’t have compulsions, but often I wind up on the internet, desperately trying to Google my way out of the panic hole. I’m not delusional–I know perfectly well that what I’m worrying about is ludicrous, and that makes me feel worse, out of control and crazy. The episode can be as brief as a few hours or go on for months.

It doesn’t help to distract myself with people and things that I love, because anything that makes me truly happy eventually becomes a focus for anxiety. The anxiety itself, the loss of feelings that were precious, and the inability to find refuge form, in combination, the most devastating mental experience I’ve ever had, and I’ve had it every year since 1994. Five years ago it came pretty close to breaking up my marriage. If there’s something good in your life, mental illness will poison it.

There’s only one coping mechanism I’ve found that has remained–fingers crossed!–unaffected: makeup.

Like many OCD sufferers, I also have a problem with depression. Sometimes my chest feels heavy, like my heart is a stone, and everything is bleak and empty and I don’t want to live anymore. It was on one of those days that I did the eyeliner look above; it helped.

There are a lot of people who take a moral position against makeup. “You’re just hiding your real face” is something they say, and they’re right–that’s exactly what I’m doing. You can’t seriously expect me to trust a world of strangers with my real face.

If I had more disposable income (or any at all, really) I’d be something close to the ideal Obsessive Compulsive Cosmetics customer. I’m an arty type, I like to slap bright colors on myself, and I hardly ever have to conform to a dress code. But I wouldn’t use OCC products if they gave them away for free.

Isn’t it David Klasfeld’s right, you might say, to deal with his condition in his own way, and discuss it however he wants to?

Yes, absolutely. But we are no longer talking about one person’s coping mechanism when we talk about OCC–we are talking about corporate marketing. OCD is David Klasfeld’s disease; OCC is his brand. It’s sold at Sephora stores across the US. You can buy it in England and Australia and Singapore. Money and time and the expertise of advertising executives have made OCC what it is. Klasfeld is selling makeup, but he’s also selling mental illness.

In his public statements, he places strong emphasis on the “positive” aspects of OCD. He has to; he probably wouldn’t move a lot of product if the name of his company were associated in people’s minds with sick, gnawing, bowel-disrupting fear. Instead he links OCD to marketable concepts such as order, precision, cleanliness, attention to detail:

“What’s been amazing about the company is turning what’s viewed as a negative into a positive,” said Mr. Klasfeld of obsessive-compulsive disorder. “Coordinating and matched sets are definitely things that are born out of an O.C.D. mind.”

—NYT

Sounds nice. But OCD is a negative. It’s not a social-model disability like deafness or Asperger’s syndrome; if everyone in the world had OCD, OCD would still make people want to die. If there were a pill that promised to cure my OCD forever but make my depression twice as severe, I’d take it. I’d commit crimes to get it.

My father was fanatically tidy and clean, the way all OCD sufferers are in the popular imagination. I’m not tidy or clean or organized, and nothing I own matches anything else. During my second year in grad school, I was afraid to be alone in my apartment, so I spent as little time there as possible; once I went three months without cleaning my bathroom. Kelp-like fronds of mold waved at me when I flushed the toilet. I am not what Obsessive Compulsive Cosmetics would like you to envision when you think of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

OCC probably doesn’t need attention-getting branding to maintain their position in the crowded cosmetics market. Unlike Urban Decay, whose line, without the veneer of danger, would be difficult to distinguish from Make Up For Ever or Stila, OCC has a genuinely unique product in Lip Tar–there is no competitor at any price point. But they’ve decided to run with the theme (their professional discount program for makeup artists is called “the Obsessive Compulsive Discount (OCD) Program”), and if it’s hurt them in the market, I can’t see any evidence of it. Even in hotbeds of activist outrage like tumblr, there’s a distinct lack of concern about OCC.

I hear a lot of jokes about obsessive-compulsive disorder, and throwaway references that aren’t really jokes: “I’m a little OCD about my spice rack.” That kind of thing. I don’t usually have it in me to call anyone out, and when I do, I’m circumspect about it, trying to get people to think about OCD as a serious illness without putting them on the defensive. One of these days it might even work. It’s hard to be sick; being a punchline makes it harder.

How would the focus groups have gone if David Klasfeld had been diagnosed with something else?

Social Anxiety Cosmetics: acronym less than ideal

Post-Traumatic Stress Cosmetics: respondents said the name evoked images of soldiers, which have a certain glamour but not the kind of glamour that sells makeup

Clinical Depression Cosmetics: “Does that mean the products only come in one color and it’s gray?”

Generalized Anxiety Cosmetics: name did not evoke anything; respondents don’t know what it means

Schizophrenic Cosmetics: respondents said it sounded “scary”

Bipolar Cosmetics: “So… everything’s either black or white?”

The general public has a warped conception of every mental illness. Obsessive Compulsive Cosmetics only works as a brand because the warped public conception of OCD happens to be marketable. OCC does nothing to combat this.

Q: Obsessive Compulsive Cosmetics? What’s up with the name?

A: “The first step is admitting you have a problem,” says company founder David Klasfeld, “I did and the result is a line obsessively crafted from the finest ingredients possible, to celebrate the driving compulsions of makeup fanatics everywhere.”

–from the OCC FAQ

It’s frightening to speak in public about being mentally ill. I probably wouldn’t be doing it right now if Emily Thomas hadn’t cleared the path. There can be repercussions. You can lose credibility; you can lose the benefit of the doubt. A guy can bull-rush you during a baseball game and break your collarbone and people will say it was your fault because you’re not normal. You become Other.

I recognize and salute David Klasfeld’s courage. But by perpetuating misconceptions and contributing to the trivialization of OCD, his company ultimately does harm to sick people. The good intentions I’m sure Klasfeld had went wrong the moment an illness became a commodity. Despite the “100% vegan and cruelty-free” promise, OCC is casually cruel.

This is not what obsessive-compulsive disorder looks like:

It looks a lot more like me, hunched over in sweat-soaked pajamas, staring without focus into the vacant middle distance, scared out of my fucking mind. It’s just not pretty.