The entire roundtable on the Marston/Peter Wonder Woman is here.

___________________

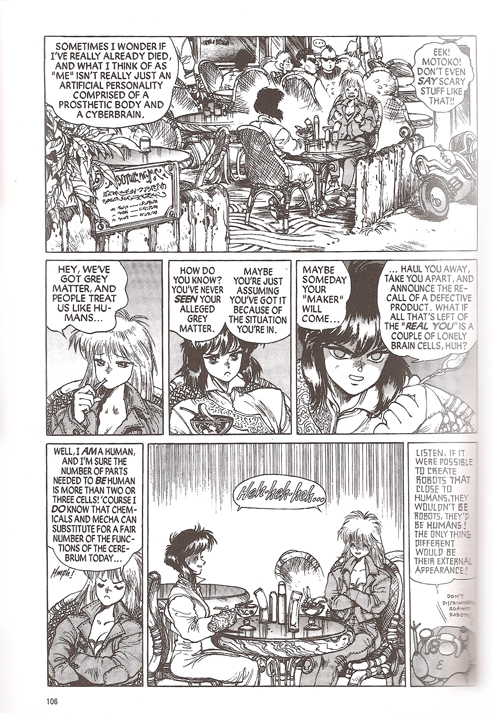

My interest in Wonder Woman has always been lukewarm, with a back issue collection ranging somewhere between Dazzler and She-Hulk. The bondage theme led me to try one of those DC Archive editions, but the mind-numbing repetition of “oh, you’ve bound my bracelets” and “now, I have you tied up with my lasso” only proved what I thought impossible: how meek and boring sadomasochism could be. I imagine what Suehiro Maruo might do with the character – questionable as feminism, true, but free of tedium. This is a roundabout way of saying I prefer my feminist icons with teeth. And William Marston wasn’t interested in artistic ambiguity, but propaganda:

[That w]omen are exciting for this one reason — it is the secret of women’s allure — women enjoy submission, being bound [was] the only truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to the moral education of the young. The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound. … Only when the control of self by others is more pleasant than the unbound assertion of self in human relationships can we hope for a stable, peaceful human society. [p. 210, Jones]

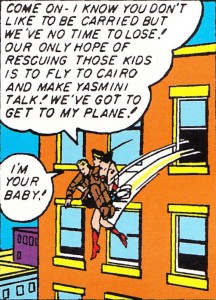

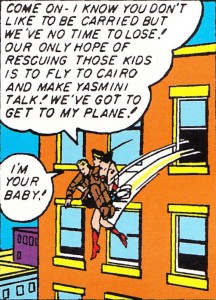

Submission as an essential quality of womanhood might sound dubiously feminist, too, if not for Marston’s insistence that what is woman’s by nature should be a virtue for man to follow. There was no Sadean intent for us perverts. Submission was Marston’s end to violence, not a subset. When moralizing critics of his day objected to the overtly fetishistic nature of Wonder Woman, Marston’s response was that bondage is a painless way of showing the hero under duress. Unfortunately, he was correct: his and Harry Peter’s depiction is about as troublingly kinky as the traps laid for Batman in his sixties TV show. As issue 28 indicates, even the villains use physical force only to subdue the heroines, never for torture: When Wonder Woman and her mom are bound by burning chains, Eviless makes it clear that the flames don’t actually burn. [p. 20] As fetish or drama, this is about as flaccid as it gets.

When I read about Brian Azzarello and Cliff Chiang’s revamped version of Amazonian culture (pun wholly endorsed), it sounded more to my taste than Marston and Peters’. I won’t repeat the argument I had with Noah about the potential in the revamping, but I would like to emphasize that I more or less agree with the idea behind the original Amazonian myth: there’s something to fear about a culture made up exclusively of warrior women. To me, feminism promotes the end to discrimination against women, but it will not rid the world of other social ills like totalitarianism, xenophobia, or any form of bigotry that isn’t directed at minimizing the humanity of women (e.g., it can be perfectly consistent with misandry and the sexist exclusion of men). As Paradise Island shows, feminism isn’t mutually exclusive to any of these ills.

If there’s a danger to Marston’s feminism, it’s in his tranquil submission to a “loving” authority. Don’t ultra-nationalists love their country? He circumvents this problem by making his heroes as anodyne as possible. We should trust the Amazonians, because we know they are pure and virtuous. Granted, this hardly sets Wonder Woman apart from all the other classic DC heroes, but isn’t that a problem? Even a feminist heroine can be as indicative of the fascistic aesthetic as any of her male counterparts. Marston’s creation helped with equality in representation, but it did so by presenting some ideas that any libertarian-minded type should find fairly repellant (and by ‘libertarian’ I mean the philosophical belief in free will, not necessarily the political variety). Fear need not lead to hatred (e.g., Marston’s Amazons don’t hate men, but they surely fear them as a social disease); it could be the basis for a healthy skepticism. Any society that promotes a totalizing agenda should be feared and distrusted, as should art promoting such an agenda, whether it’s rooted in misogyny or feminism.

Wonder Woman and the Objectivist

If Marston had a perfect Earth 2 counterpart, it would look a whole lot like his contemporary, Ayn Rand. Where he promoted the collectivist submission of self to others, she viewed self-assertion as the highest virtue and altruism as evil. He was resolutely feminist, she resolutely anti-feminist. His heroic ideal was female, hers male. What’s interesting is that despite Rand’s libertarian bona fides, she basically agreed with Marston that the essence of woman is to “submit to a loving authority”:

For a woman qua woman, the essence of femininity is hero-worship – the desire to look up to man. “To look up” does not mean dependence, obedience, or anything implying inferiority. It means an intense kind of admiration; and admiration is an emotion that can be experienced only by a person of strong character and independent value judgments. … Hero worship is a demanding virtue: a woman has to be worthy of it and of the hero she worships. Intellectually and morally, i.e., as a human being, she has to be his equal; then the object of her worship is specifically his masculinity, not any human virtue she might lack. … Her worship is an abstract emotion for the metaphysical concept of masculinity as such. [from “About a Woman President,” quoted in Gramstad]

They just disagreed on the gendered structural ideal to which women should “look up.” As Thomas Gramstad lists them (because no way in hell am I going to bother reading the author herself), the characteristics Rand was likely thinking of as ontologically masculine heroism are the regular, positive clichés one associates with phallic power: “being strong, enduring, independent, verbally accurate, competent in making and using tools, persevering and excelling in one’s activities, and in the ability to organize and lead.” A good woman has the ability to recognize such virtues as deserving of worship by possessing some of the classic feminine clichés: “emotional openness, the ability to listen and nurture, being cooperative, easygoing, warm, loyal, playful, adept at non-verbal communication skills, and able to identify and express emotions.” [ibid.] Rand was adamant that a woman could never be a hero, only a hero-worshipper. To attempt the latter would be a denial of her ontological/structural femininity. Despite her disavowal in the quote above, it’s hard to see how this view doesn’t promote the inferiority of women and their need to be dominated by men, a de facto submission.

Marston, however, had no trouble with submission; it’s the moral obligation of his heroes. So Steve Trevors makes a good contrast to Rand’s heroic ideal. As a feminist parody of Lois Lane and the superhero’s imperiled significant other, Steve is a neutered joke on that most manly of professions, the soldier. He’s what Valerie Solanas called — in her own mocking of phallocentrism, S.C.U.M. Manifesto — an auxiliary member, “encourag[ing] other men to de-man themselves and thereby mak[ing] themselves relatively inoffensive.” [p. 21, Solanas] (She could’ve provided another alternate Wonder Woman preferable to the real thing, with far more imaginative uses of the lasso, I’m sure.) If little boys saw him as a sissy with not much to admire, maybe they should consider that’s the kind of role model little girls are saddled with their whole life. But Marston wasn’t doing satire. Little boys were to aspire to be more like Lois Lane than Superman.

Where does all this knee-bending end? With a nod to Aristotle (a favorite of Rand’s): Man submits to Wonder Woman, she submits to Hippolyte and the gynocentric dogma of Paradise Island, which is derived from Aphrodite. But does the goddess obey a higher principle, or is she, by sheer force of will the loving authority sui generis, the prime lover? You’re going to reach a dominating will or order at some point that’s not submitting to anything higher. Despite all the chauvinistic nonsense (and there was plenty), Rand attempted to identify responsibility within the self, rather than have the individual relinquish control to another, whereby an authority is entrusted to follow whatever moral principles Marston believed to be beyond the individual’s grasp. Thus, I find Gramstad’s feminist correction of objectivism a far more consistently moral view than either Marston’s or Rand’s. Accordingly, heroic virtue shouldn’t be seen as gendered, but “androgynous,” borrowing from the instrumental and expressive values commonly identified within the respective provinces of “masculine” and “feminine.” Nor should one act as the heroic model because of obedience, but through autonomous agreement with the various characteristics constituting that model.

If Marston’s argument for being bound doesn’t sound like fascism’s bundle of sticks, it’s because his fantasy of Wonder Woman always has her using Amazonian power in the most decent way possible. Well, that, and because fascism is assumed to be the prime example of knuckle-dragging masculinity. In his argument against separating cinematic form from fascistic function (“Fascism/Cinema”), Robin Wood identifies certain tropes of Leni Riefentahl’s Triumph of the Will as latently fascistic, if not explicitly so, wherever they appear [p. 19-23]: empty rhetorical speeches connoting nationalism and ideological purity as the solution; dehumanized spectacles of people functioning as a machine; phallic power display; the indoctrination of children into “the dominant ideology (patriarchy, capitalism) as unquestionable fact and truth”; an obsession with cleanliness and work (e.g., alienated labor is spun as service to the represented ideology while a pleasurable activity such as sex is repressed and seen as dirty); the ideology is represented as the inherent vox populi [1]. If a woman can be the fascist auteur, why can’t a feminist society be fascist?

Despite its presentation as a revolutionary utopia against patriarchy, Paradise Island exhibits all of these tropes (and I’m just talking about issue 28): Men aren’t allowed on the island for fear of contamination (ideological purity and nationalism). The Amazonian view is presented as unquestionable fact in the empty rhetoric of Hippolyte, which sounds like she had one of the pod people from Invasion of the Body Snatchers as a speechwriter: “The only real happiness for anybody is to be found in obedience to loving authority.” [p. 48] As already seen, Marston intended to indoctrinate children into his counter-ideology (the dominant ideology of the Amazons). Just like the throngs of people cheering the Nazis on in Reifenstahl’s film, all the Amazons seem to be of one mind (which goes along with Marson’s notion of a “a stable, peaceful human society”). Whatever fetishistic quality bondage might’ve had for Marston personally, its use in his comic is always in service of the Amazonian ideological state apparatus. When the lasso falls into the hands of Eviless, the solution is not to destroy such a dangerous tool, but for the proper authority to regain its control (normalizing the kink as productive work in place of the dangerous and mysterious world of private sexuality). Should anyone be unwilling to submit to the loving Amazonian authority, Wonder Woman never has a problem with classic “phallic” displays of purely violent repression (presumably a transitory measure like the temporary dictatorships of utopian leftist thought). And, like a clockwork orange, these unruly types are sent to Transformation Island for a Venus girdle fitting and re-programming [2].

Wonder Woman and the Utilitarian

Liberal do-gooder resistance to retributive justice can often slip into the most totalitarian of utopian ideas. By focusing on utilitarian notions of rehabilitation and deterrence, rather than a just punishment to fit the crime, the criminal’s agency can be diminished for the general good. What results is a society that begins to look like a penal colony. There are the science fiction dystopias such as A Clockwork Orange and The Minority Report, but also B. F. Skinner’s utopian model for the real world, Walden Two, where a centrally planned system of positive reinforcements has eliminated crime through the shaping of behavior (the behaviorist had no truck with talk of free will, Beyond Freedom and Dignity being one of his major popular works). And, to my mind, Marston’s Transformation Island is a more horrifying, feminine version of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon.

The concept is ubiquitous nowadays (cf., the masthead above), but briefly: The panopticon is a circular prison with a watchtower in the center covered in two-way mirrors, where guards can observe any of the prisoners through the glass walls of their cells that face the tower. It’s a model of efficiency: few to no guards are needed at any given time, because the prisoners can’t determine when they’re being watched. Thus, they learn to act as if they’re always being watched. Besides the obvious visual analogy of the tower to the phallus, the concept can be read as masculine due to its use of Laura Mulvey’s “male gaze.” [3] Similar to what’s done with Rear Window, substitute the film audience for the guards, the screen for the glass walls and images of women for the prisoners, and you pretty much have her view of cinematic pleasure. The woman/prisoner exists as spectacle (connoting “to-be-looked-at-ness”), “freezing”/disrupting the progression of narrative/legal order, which is what the masculine camera/guard’s gaze is ultimately searching for: “This alien presence [erotic or criminal spectacle] then has to be integrated into cohesion with the narrative [patriarchal or legal order].” [4] [p. 203, Mulvey]

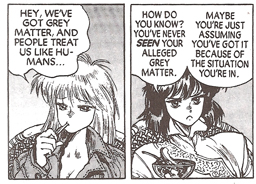

Transformation Island’s rehabilitation isn’t merely concerned with controlling behavior, or what can be seen, but in the complete restructuring of the criminal’s affective states and desires. As Ken Alder points out, the early popular reports on Marston’s beloved polygraph tended to code its subject as feminine due to stereotypes of women “as emotional, secretive, and deceitful, identifying them with ‘nature’.” [p. 9] Similarly, Amazonian rehabilitation is “feminist” because it goes beyond the conscious expressions, behind the visible and, of course, replaces the typical male rational observer with the care of matriarchal authority. A successful transformation occurs when the subject not only conforms to Amazonian law, but willingly resists being freed from the psychic chains of her Venus girdle. There is no engagement with the subject as an individual, only a one-size-fits-all, Manchurian Candidate-styled reformatting of the transgressive will with a servile Amazonian one (such as the reformed Irene [p. 21]). I guess the Borg could be seen as a peaceful society – I mean endogenously, they’re matriarchal, work well together and always remain so calm – but is it anyone’s idea of a loving authority? Maybe Marston’s. Irrespective of gender alignment, this is pure dehumanizing objectification being sold as loving care.

The panopticon is particularly scary as a structuring metaphor for society itself. People willingly displaying themselves on online social networks and getting accustomed to the accretion of cameras in banks, businesses and on the streets are instances of Shoshana Zuboff’s “anticipatory conformity”:

I think the first level of that is we anticipate surveillance and we conform, and we do that with awareness. We know, for example, when we’re going through the security line at the airport not to make jokes about terrorists or we’ll get nailed, and nobody wants to get nailed for cracking a joke. It’s within our awareness to self-censor. And that self-censorship represents a diminution of our freedom. [quoted in Cox]

As the sense of privacy erodes, people modify their behavior to fit what the omnipotent gaze, the collective will, wants. The Amazons are much more Orwellian, erasing and rewriting the self until it conforms to their utopian ideas (Newspeak is dialectic compared to the Venus girdle.) And Marston thought this absolute dominance a good message to promote to children, all for some twisted version of feminism. Again, totalitarianism and feminism are not mutually exclusive.

Rest up and come back for the thrilling conclusion tomorrow.

Footnotes:

[1] I don’t disagree that much of this imagery is always potentially fascistic, only that it can’t still be appreciated for it’s formal beauty as such. Wood (following Mulvey) uses the example of Busby Berkeley’s spectacles in a fairly dismissive tone due to the objectification of women for the male gaze, as if simply appreciating their organized beauty is little more than swallowing fascistic rhetoric. Putting aside the issue of whether such objectification is always bad, I can’t help but think of Claire Denis’ equally beautiful and “mechanized” movement of the French Foreign Legion in Beau Travail. It is militarized, organized and very phallic, but is that all there is to it? (Clips of both examples can be easily found on YouTube.) To reduce all appreciation of these examples to the dehumanizing and totalizing gaze seems entirely too simplistic, even where there is a penumbra of fascism. Fascism has to have some appealing qualities; otherwise, no one would ever freely choose it.

[2] I’m not the only one to connect Wonder Woman with fascism:

On the surface at least, William Marston’s texts for Wonder Woman — a self- proclaimed feminist hero — subverted these [patriarchal] stereotypes. […] Yet Wonder Woman fights Dr. Psycho with tactics that hardly differ from the dissembler’s own fascist propaganda. Although she espouses liberal rhetoric and is a fierce advocate of feminist equality, when she ties up Dr. Psycho with her truth lasso, he is obliged to tell the truth. Bound by her lasso, Wonder Woman’s adversaries are ‘‘forced to be free.’’ [p. 9, Alder]

[3] Too much credence has been given to the genderification of the kinoeye. Before Mulvey’s essay, the subsequent explosion of gaze types (sadistic, male, masochistic, female, transcendent, etc.) and critiques from other feminist theorists like Kaja Silverman, Linda Williams and Carol Clover, the supposedly sadistic voyeur par excellence, Alfred Hitchcock, had already implicitly dismantled such an idea with his notion of suspense. That is, the filmmaker creates suspense by giving the audience more knowledge of the danger faced by the protagonist (with whom the audience identifies) than the character has. The way Hitchcock often did this was by placing the camera with the villain. This pro forma technique doesn’t assert identification with the villain, but, quite to the contrary, creates a sympathetic fearful affect for the protagonist, male or female. Silverman suggests much the same in “Masochism and Subjectivity”:

I will hazard the generalization that it is always the victim — the figure who occupies the passive position — who is really the focus of attention, and whose subjugation the subject (whether male or female) experiences as a pleasurable repetition from his/her own story. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that the fascination of the sadistic point of view is merely that it provides the best vantage point from which to watch the masochistic story unfold. [quoted in Clover, p. 105]

While Clover (in the same essay from which the above quote was taken) tempers her theorizing with the observation that a camera is sometimes just a camera. [p. 90-1]

[4] I’d grant that this is an analogy, not a homology: According to Mulvey’s psychoanalytic approach, dealing with the alien presence is really a way of decreasing castration anxiety. The “two avenues of escape” for the male unconscious are sadistic voyeurism (“pleasure lies in ascertaining guilt […], asserting control and subjecting the guilty person through punishment or forgiveness”) or fetishistic scopophilia (“the substitution of a fetish object or turning the represented figure itself into a fetish so that it becomes reassuring rather than dangerous”). [p. 205] Both avenues might be pursued in the integration of a narrative female figure, but unless the criminal is a femme fatale, only voyeurism would seem applicable in the panopticon.

Update: Read part 2.

References:

Alder, Ken, “A Social History of Untruth: Lie Detection and Trust in Twentieth-Century America” (2002), a .pdf download from author’s website.

Clover, Carol J., “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film” (1987/1996) in The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, Barry Keith Grant (Ed.): p. 66-113.

Cox, John, “The Evolution of Surveillance: Security Comes with a Cost” (2009) on the author’s website.

Creed, Barbara, “Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection” (1986/1996) in The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, Barry Keith Grant (Ed.): p. 35-65.

Gramstad, Thomas, “The Female Hero: A Randian-Feminist Synthesis” (1999) on POP Culture: Premises of Post-Objectivism.

Jones, Gerard, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book (2004)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975/1986) in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, Philip Rosen (Ed.): p. 198-209.

Paglia, Camille, “No Law in the Arena” (1994) in Vamps & Tramps: p. 17-94.

Solanas, Valerie, S.C.U.M. Manifesto (1968) on UbuWeb.

Williams, Tony, “Phantom Lady, Cornell Woolrich, and the Masochistic Aesthetic” (1988/2003) in Film Noir Reader (7th Edition), Alain Silver & James Ursini (Eds.): p. 129-143.

Wood, Robin, “Fascism/Cinema” (1998) in Sexual Politics & Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond: p. 13-28.