Noah Berlatsky brings up some interesting points in his essay “Why Do We Love Batman But Hate Superman?”, observing the Superman v Batman trailer as yet another incarnation of society’s desire to see “normal guy” Batman kick Superman’s “alien other” ass. But Superman’s journey from Man of Tomorrow to lame old-timer represents a complicated trail, the character walking a razor’s edge between the ephemera of junk culture charm and the drive to make superhero stories—and likewise their creators and devotees—seem “mature.” There’s a tension: expecting a fictional character to continue to serve as DC Comics’ figurehead, often in the face of public indifference, while constantly facing reinvention in a struggle to maximize corporate gain. If someone can be heard rattling off a list of favorite Superman comic book stories, odds are he or she is over 60 years old. Conversely, my wife, who was 8 years old upon the release of the Tim Burton Batman movie that in many ways is ground zero for mass-marketed superhero cinema, often tells me her peer group “never thought Superman was cool.” (I’m ten years older, so I got to see Superman become a movie star firsthand.) Much like when rock fans speak of Elvis Presley, there seems to be a fear of sounding like an uninformed clod if you don’t pay polite lip service to notions of Superman’s “importance” and “influence,” yet the particulars of just why the Man of Steel had such resonance, and to whom, has become an increasingly distant cultural memory.

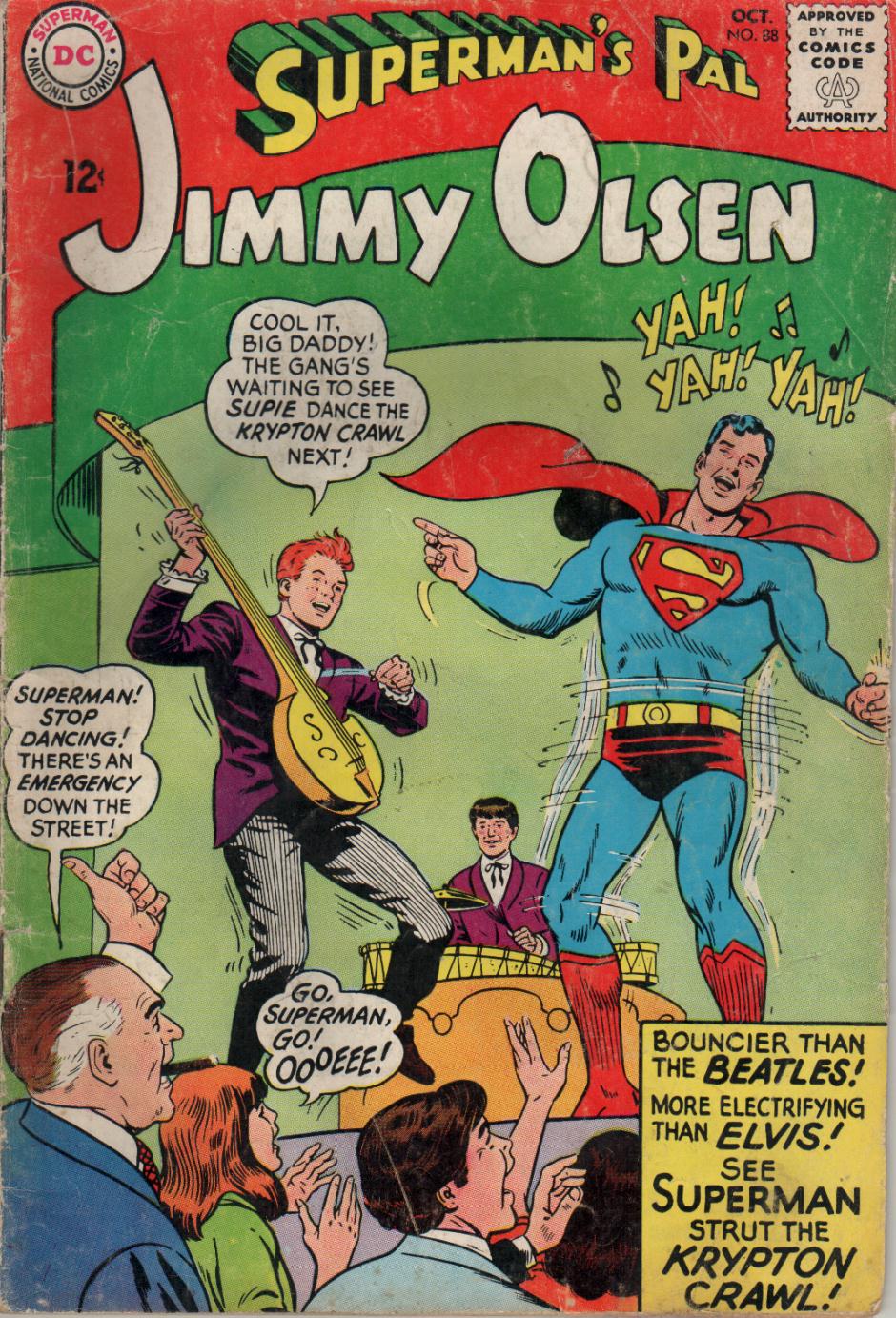

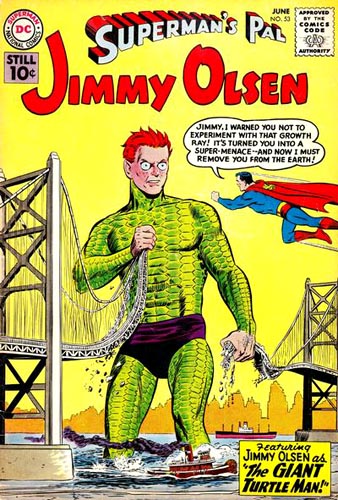

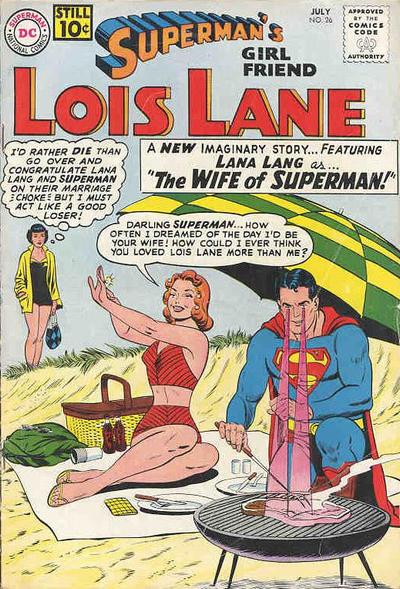

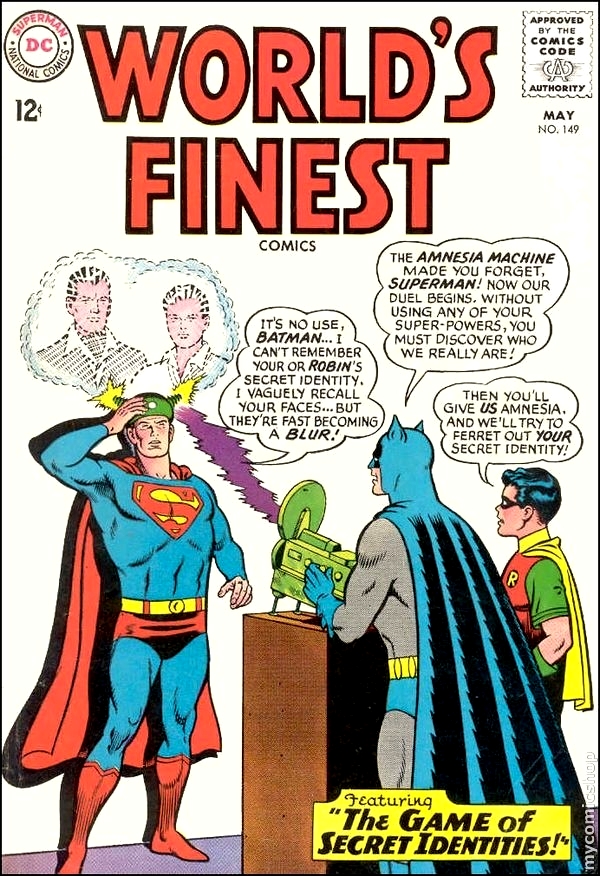

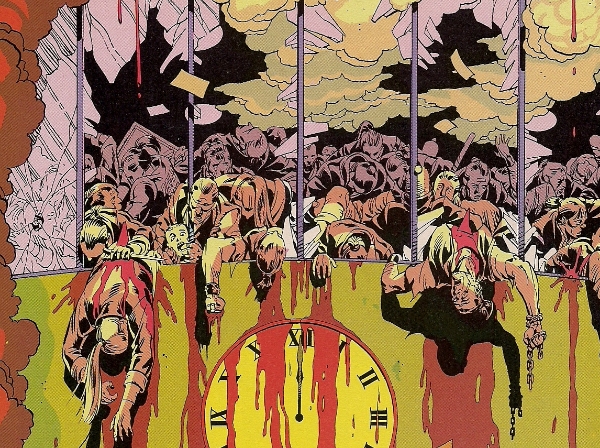

Superman maintained a unique position among the raft of superheroes that arrived in his wake, not only enjoying a media profile beyond comic books (newspapers, radio, cartoons, television, stage, movie serials), but also being one of the very few to remain in publication through the Forties and Fifties. Editor Mort Weisinger oversaw the character’s renaissance beginning in the late-Fifties, with enduring concept seemingly introduced every few months (within a year and half: the Bizarro World, Supergirl, the Phantom Zone, Red Kryptonite, the Legion of Super-Heroes, “imaginary stories,” the Fortress of Solitude, the Bottle City of Kandor). The comics took on a sense of craft and charm reminiscent of the Forties’ top-selling superhero, Captain Marvel—fitting, since many of these concepts were originated in the scripts of Otto Binder, looking for work after CM was driven out of circulation by DC’s litigation. In the 1960s, the top 10 selling comic books in America regularly contained all seven Superman titles: the perfect entertainment for 8 year olds, full of arctic hideouts and robot doubles and a city in a bottle and an imperfect duplicate of Earth and bizarre transformations and outlandish coincidences, packing more plot into 8 page stories than some 6-issue “arcs” do today. But the very strengths that made these comics appeal so much to children—whimsy, fairy tale-style fantastic sweep, enchanting emotional drama, majorly unpredictable weirdness—became an Achilles’ heel to the expanding comics fandom who didn’t feel the need to outgrow comic books, but also didn’t want the public to think less of them for their tastes. Many of these young fans became the generation of comics creators who filled the shoes of those who wrote, drew and edited such “kids’ stuff” as they moved on or passed away; the young crowd knew things had to change.

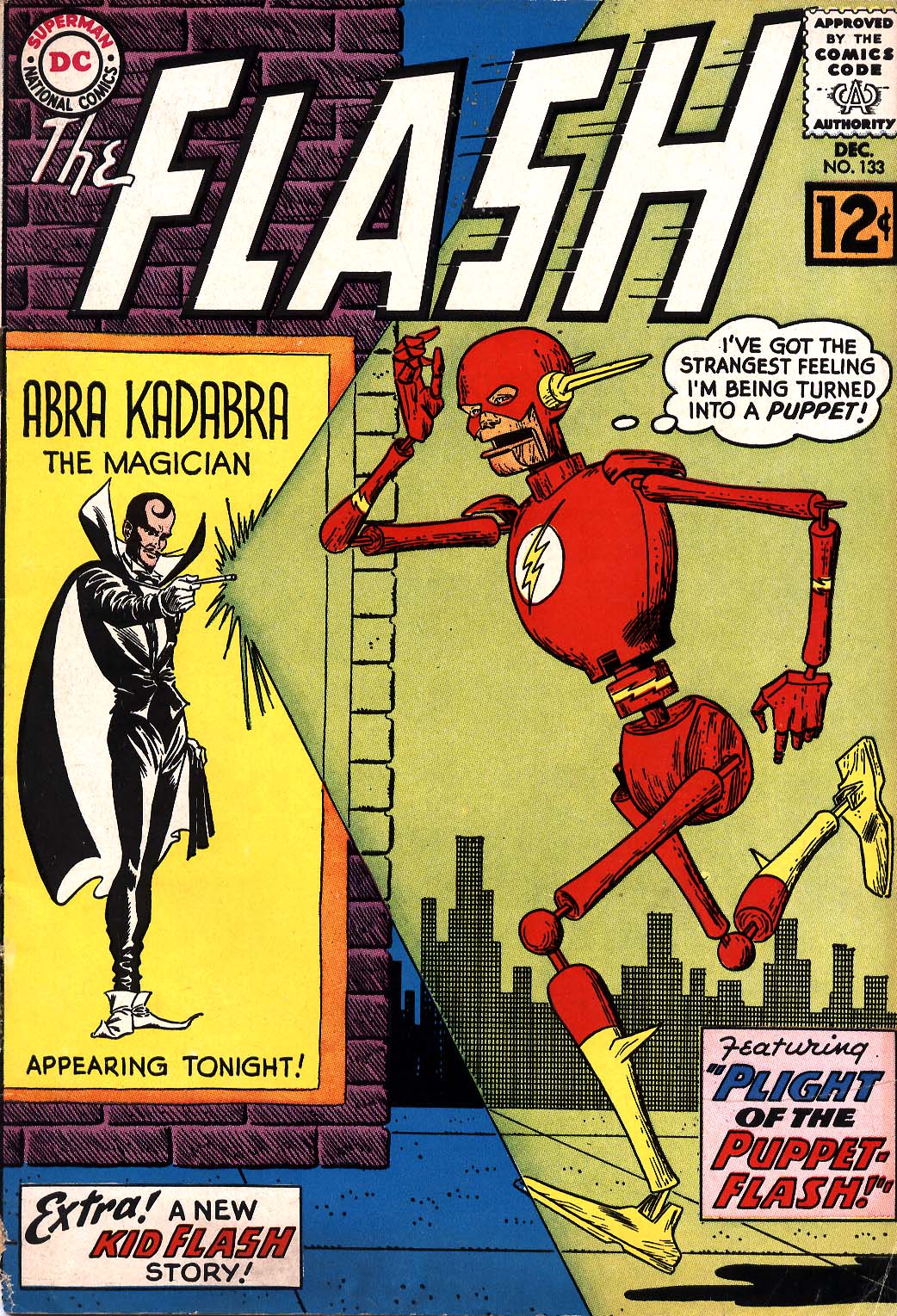

After Weisinger retired in 1970, the difficulty was finding an adequate encore. Current Superman comics were seen by an increasingly older comics audience as bland, workaday filler; no better or worse than the majority of Seventies superhero books, really, but nothing to write home about either. Marvel’s rise to dominance through the ’70s was sold on Stan Lee’s hype job that Marvel was the “collegiate, intellectually complex” superhero line, and DC was increasingly seen as juvenile and tiresome. “Realism” was the buzzword of the day, from Marvel’s strategy of angst-ridden “superheroes with problems” to Neal Adams’ grimacing poses. But the easy appeal of those ‘60s Superman comics shows up the misguided thinking in subsequent attempts to graft contemporary ideas of “character development” or slambang action onto the series. The Marvel-style approach has often been compared to soap opera: heavily continuity-driven, with suspense built by ongoing angsty personal lives and dramatic installment-to-installment serial rhythms. Whereas Silver Age DC stories are closer to the model of the situation comedy, starting at the same default “normalcy” each time, presenting a disruption in that comfort zone, and returning to the starting point upon denouement. Squareness was the point of old-school DC: instead of heroes with feet of clay, these square-jawed, confident crimefighters were most put out by humiliation. Just as likely as villain-of-the-month conflicts were cover gimmicks promising the latest violation of the hero’s sacred dignity (the infamous Flash cover with the thought balloon, “I’ve got the strangest feeling I’m being turned into a puppet!”). Red Kryptonite or a Mxyzptlk curse or a flask of potion could turn Superman or Jimmy or Lois into any number of beasties, grant a third eye, make them fat, what have you—the angst in Silver Age DCs is all about “how do I get through the day without someone noticing my face is a living mood ring,” much more entertaining than Hank Pym’s marital strife. (I wish I could remember which of my friends to credit with the astute observation that, when you hear people complain about DC’s “cardboard characters” in relation to Marvel’s “fully rounded personalities,” it sounds more like they’re speaking of Hanna-Barbera’s TV show Super Friends than actual familiarity with the comic books.)

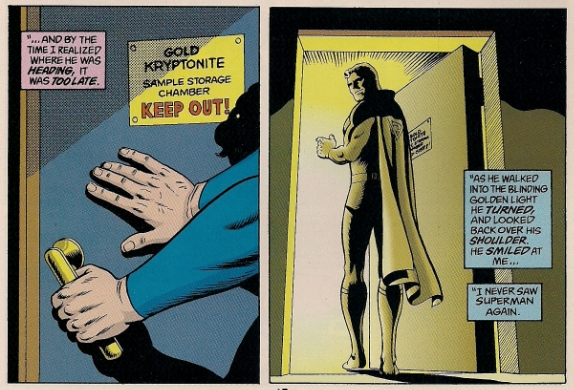

As of the mid-1980s, notions of DC’s second-class-citizen status mostly held steady with the fan populace, but with an increasing view that Batman was the exception that proved the rule. Morphing from corny Caped Crusader to menacing Dark Knight, Batman was seen as a rare example of a “badass”/”complex” superhero amongst DC’s largely cool/cerebral personalities—DC’s only real competition for Marvel’s “dangerous”/”gritty”/”street level” Wolverine/Punisher types in those pre-Lobo times. DC’s few thriving sellers tended to be from the dustier corners of their continuities, spun on the appeal of the X-Men-style team book dynamic—Teen Titans, Legion—and the Superman/Flash/Green Lantern DC mainstream that was so appealing during the ’60s seemed to remain in print more out of habit than honest enthusiasm. The Crisis on Infinite Earths “event” was designed to “clean the cobwebs” from DC’s backlogged continuity (read: eliminate the goofier aspects to prevent fan embarrassment). Superman and his pals were presented as having the biggest need for this push, so away with Supergirl, pets with capes, Bizarros, and so forth. “Post-Crisis” attempts to reinvigorate what came to be known as the “Big Three” did wonders for Batman, via the efforts of Frank Miller et al, but even the appointment of fan favorite creators couldn’t reverse the lasting impression that Superman and Wonder Woman were for squares.

By the ’90s/21st century, the party line on Superman within an increasingly influential fan populace was that he was to be condemned as “the Big Blue Boy Scout,” a clueless, morally-uptight fossil looking lost in a time of antiheroes and fashionable ultraviolence. A counterrevolutionary, if you will. Younger fans tended to observe Superman as an empty personality-free shell merely occupying a necessary merchandising trademark, like they might with Mickey Mouse. From the distance that I observed the megaselling “Death of Superman,” those millions of comics seemed to sell to A] aging former readers of Weisinger’s comics who hadn’t touched the stuff in years and/or B] investors eager to resell these comics—actual enthusiasm among current comic book readers seemed difficult to pinpoint. And of course, the press releases implicitly sold the line to a cynical public that Our Hero’s worth had been exhausted in this cold, hard world, and it was time to do away with the poor old relic. (Veteran comics readers had been led down this garden path a few times and knew better—he wouldn’t “stay dead” for long.)

Today, selling fanboys on the idea that Superman is at all interesting, let alone “cool,” always seems to involve some menacing, “intense” image, all gnashed teeth and smoldering laser-beam eyes; a far cry from the placid, smooth Curt Swan model of prior decades. The occasional well-received effort, like Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely’s All Star Superman, seems to have an easier time gaining traction with older readers—and, tellingly, invoke the long-abandoned tropes of those still-intriguing ’60s stories, with their reliance on “silliness” like super-pets and signal watches. Another take is to remove as much of the superficial resemblance to the franchise as can be achieved—the marketing for TV’s Smallville (and the producers’ pithy mantra, “no tights no flights”) seemed designed to scream, “This is not your father’s Superman.” 2006’s Superman Returns consciously attempted to wipe away memories of the ill-received third and fourth Christopher Reeve films by following up plot threads of Superman II—perhaps not coincidentally, just about the last point in time the larger public’s finger was on the pulse of a Superman story.

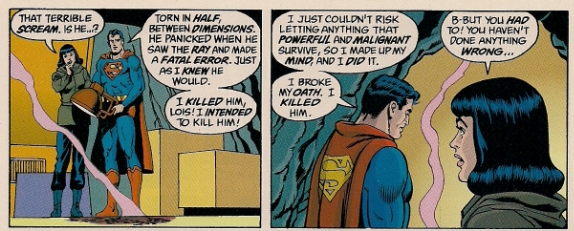

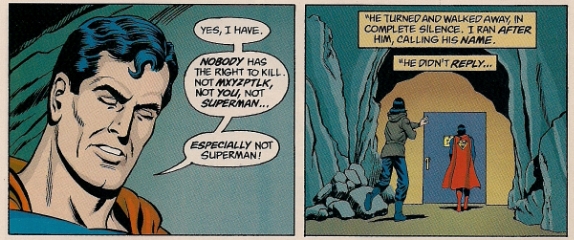

The frosty reception for Superman Returns seemed to be painted by some as evidence of the character’s lack of appeal or relevance to modern audiences, leading to that major overhaul in the face of commercial panic, the “reboot.” (After Hollywood was caught off guard by the blowback over Michael Keaton’s casting as Batman, making fandom unhappy has been seen as the quickest route to monetary oblivion.) The Man of Steel movie gained much controversy over its fatal climactic moments, with much online debate about “destruction porn” and proposing ways the story could have been led to avoid Superman taking deadly action. But the makers of the film seemed to coldly calculate exactly the effect they were looking for—giving audiences who aren’t wired to like Superman the shock effect of a Man of Steel who kills. Inserting Batman into MoS’ sequel seems like a box office insurance clause as much as a response to any desire to see the two duke it out; the view that DC has spent decades following Marvel’s lead isn’t abated by the impression created by cramming four more heroes into what is nominally “a Superman film,” just so Warner can fast track their own “cinematic universe”.

Striving to navigate the appealing fantasies of childhood into escalating “darker” territory keeps leading to nastier dividends. Witness Identity Crisis, a miniseries that proposed that, behind the veneer of kiddie-comic cheeriness, those buffoonish villains in tights you read about as kids hid rapist impulses; it was truly depressing to overhear the comics-shop water cooler conversation turn to this being the way “DC should have done it all along.” The cliché goes that audiences like Batman because anybody can work out and build gadgets and blow stuff up (as long as you’re a millionaire who lives in a fantasy setting, I guess), but supposedly nobody can relate to Superman because he’s “too powerful” (the usual complaint about past incarnations of the Man of Steel is that he could “juggle planets,” even if nobody can offer an example of this actually happening). It becomes about the usual concerns of “who can beat up whom,” the appeal of Superman assumed to be that he’s stronger than everybody else while struggling to maintain drama by coming up with somebody strong enough to fight back.

Almost every reboot attempt goes further in making Superman less connected to his Kryptonian heritage, more a “regular guy” like Batman, depowered to reduce those godlike abilities and make for more thrilling fisticuffs. But the “childish” fantasy of Weisinger’s Superman—who could destroy planets with a sneeze or perform plastic surgery with his fingertips!—didn’t make for less interesting stories; that “anything can happen,” wild card element led to the most outlandish and unpredictable plots imaginable. Those looking to recapture the appeal of Superman could do worse than learn from the successes of the past, rather than refute them.