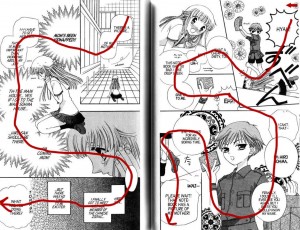

When Noah first asked me if I’d like to write a guest post for The Hooded Utilitarian, he mentioned that he’d be especially interested in something about Twilight. I admit I originally balked at the idea. Though I’ve vocally defended the series’ fans, I haven’t read the novels, and my only significant reaction to the first volume of Yen Press’ graphic novel adaptation was that it was more readable than I expected.

That last statement should not be taken as a condemnation of Twilight by any means. The truth is, I’m simply not its audience. I like a good romance as much as the next middle-aged married lady, but even those who dismiss the genre would be foolish to assume that all romances are created equal. Simply put, I’m too old for Twilight. While my teenaged self might not have fully comprehended Stephanie Meyer’s bloodlust = regular ol’ lust metaphor (not that it’s especially subtle), she would have felt it in a profound way. It would have resonated with her on a deeply personal level. I was pretty innocent as a teen, and the concept of even kissing a boy was both enticing and mind-blowingly terrifying, much like Bella’s first kiss with her sparkly, bloodthirsty suitor, deep in the secluded woods.

Now in my forties, I know all too well that sex is the least terrifying element of romance. Love’s true horrors prey on the heart and mind, and there’s nothing you can buy at Walgreens to help protect them. Looking in at Twilight from the reality of weary adulthood, it’s difficult to muster patience for Edward’s martyred bad-boy act (just as it’s difficult to stomach Bella’s fascination with it) but I can recognize it as something that, if it was written for me at all, was written for the me of a very different time and place.

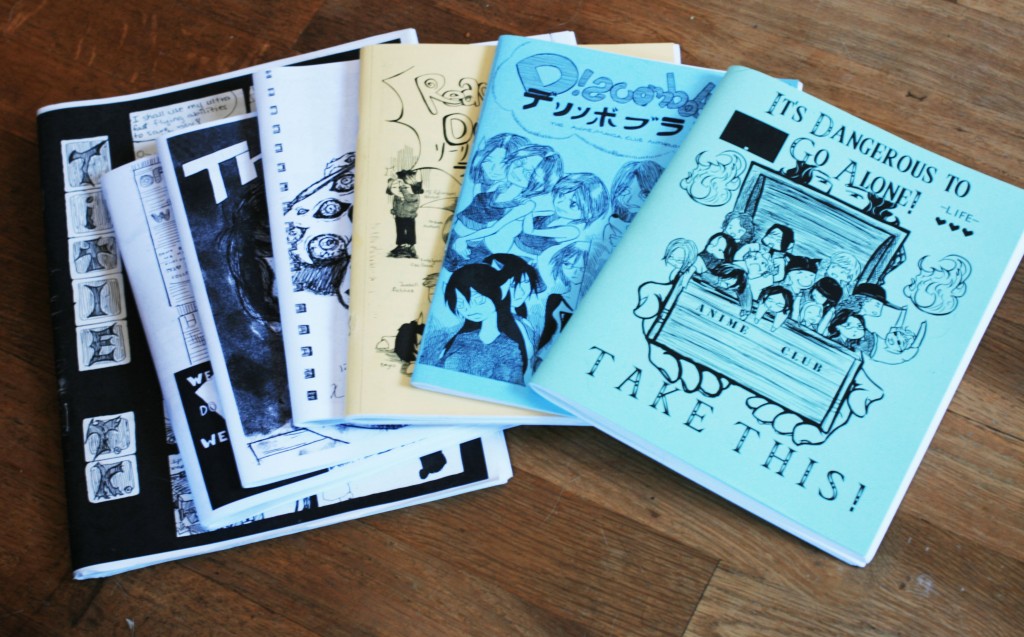

A second read-through of the graphic novel has only cemented my original opinion of it, but even so, I feel a kind of kinship to the series’ young fans. Having spent my entire life obsessed with some kind of fiction or another–books, television, musicals, manga–I can appreciate their need to experience the series over and over again, to talk about it with friends, and to proselytize everyone they meet. Sure, it’s obnoxious, but how many long-time genre fans can honestly claim that’s never been them? I know I can’t.

Earlier this year, just before the first volume of the Twilight graphic novel was released, I made a post in my blog about the manga and anime fandom’s treatment of Twilight fans. In that post, I cited a few overtly misogynistic comments made by male fans, and proposed a theory that the real “problem” with Twilight fans in the eyes of fandom is that they are overwhelmingly girls. That’s a pretty easy accusation to make against nearly any genre fandom. We’ve all heard stories of women who’ve been ogled, condescended to, or otherwise mistreated in comic book shops, at conventions, in online forums and so on, and most of us have experienced this at some point or another ourselves.

What I think I missed back when I wrote that post, however, is something far sadder than a bunch of paranoid fanboys making an angry fuss on the internet. What’s more disturbing to me now–something I began to see bubbling up in comments and responses to that post–is a trend of women in manga and comics fandoms deliberately distancing themselves from other women (or from works created by/for women in the medium, teen romances or otherwise) as an apparent matter of pride. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not suggesting that women have an obligation to like works created by other women, or even the women themselves. We like what we like, and there’s not a lot more to be said about that.

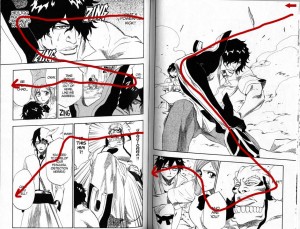

The thing is, we are saying more. We’re ranting and denying and over-explaining ourselves, all in an attempt to ensure that we can’t be associated with anything “girly.” Take, for instance, this recent post from Molly McIsaac at iFanboy.com, “Turning Japanese: A Starter Guide to (Shoujo) Manga” (and let me apologize to her now for choosing her as my example). In this post, Ms. McIsaac strives to cut through all the girly stuff and point readers to some shoujo manga with “good, solid stories and strong characters.”

We’ll gloss over the fact that she likens shoujo manga to Craig Thompson’s Blankets (which, as a story of one man’s coming to terms with his spirituality, most closely resembles a particular brand of seinen, if anything at all), and that none of her shoujo “staples” goes back any further than 1996. All any of this indicates is that she’s fairly new to the medium and has yet to really experience its breadth (and hell, some of that older shoujo is pretty hard to find in print). None of this has anything to do with my problem.

What I’m getting around to here is the fact that Ms. McIsaac seems to feel that she has to offer up disclaimers for reading shoujo manga at all. I’m also bothered by the strong implication that manga for girls is antithetic to solid stories and strong characters. “However, do not allow shoujo manga to intimidate you,” she says. “Although it is aimed primarily at young women, there are plenty of good, solid stories that are considered shoujo that I believe most people can enjoy.” If even women feel they need to make these kinds of excuses while recommending manga written for (and primarily by) women and girls, how can we expect any of that work or the fans who read it to be respected by the larger fandom?

Again, I’d like to apologize to Molly McIsaac. This attitude about girls’ comics has most likely been passed down to her by scores of female fans who came before, shuttling around borrowed volumes of Boys Over Flowers to each other with quiet embarrassment, wishing they looked just a little less sweet and sparkly.

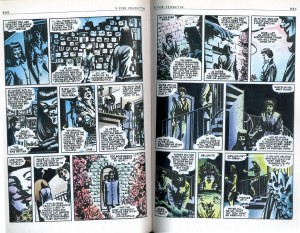

Honestly, I’ve done this myself. How many times have I complained about the hot pink Shojo Beat branding on the outside of Viz’s editions of NANA, claiming that it trivializes the series and makes it embarrassing to read on the plane? (The answer is, “Many, many times.”) Yet I can think of several pink, sparkly, decidedly “girly” manga (at least one of which is written for little girls) that are more well-constructed, deftly plotted, and philosophically-minded than many of the comics I’ve seen published for, say, boys or adult males. Though these manga are certainly girly, they’re hardly lightweight. Even so, just two years ago, I sat in on a convention panel at a nearby women’s college, where one of the pro panelists (a female sci-fi writer) told the entire room full of young women that all shoujo manga was plotless high school romance and that whenever she saw girls looking in the manga section at her local comic shop, she’d direct them towards “more interesting things like Bone.”

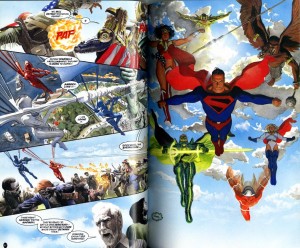

What does any of this have to do with Twilight? Well, nothing and everything, I suppose. If female manga and comics fans have any hope of adjusting men’s attitudes about our presence in “their” fandom, we really need to start by adjusting our own. I’m probably never going to really like Twilight (in graphic novel form or otherwise)… or Black Bird, or Make Love and Peace, or any number of particular girls’ and women’s comics I’ve picked up and discarded for various reasons.

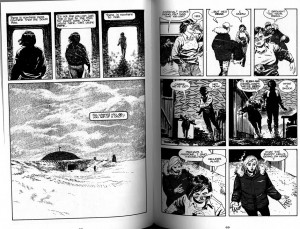

I’m also never going to like Mao Chan, KimiKiss, Toriko, the Color trilogy, or any number of other comics I’ve rejected that were written for boys or men. Yet the existence of these boys’ and men’s series I don’t like has never made me feel like I have to apologize for or explain why I still read things like Fullmetal Alchemist, Children of the Sea, or Black Jack. “Well, it’s written for guys, but it’s still good, I swear!” That’s a sentiment I have yet to see expressed by comics fans on the internet, female or otherwise.

So what is it about “girly” comics that puts us so on the defensive? Are we seeking approval from male fans? Do we believe we have to publicly reject all things stereotypically feminine in order to obtain (or maintain) credibility in fandom? If so, I submit that we’re actually playing right into the attitudes that kept us alienated in the first place. And if we’re doing it to establish credibility amongst ourselves, we’ve lost to them completely.

– Read Melinda’s reviews and discussion of manga, manhwa, and other East Asian-influenced comics at her blog, Manga Bookshelf.