This post first ran on comixology.

__________________

Over the last decade, imported Japanese comics, or manga, have gained a huge following among young girls in America. One of the most successful, and most startling, genres has been shonen–ai or its more explicit sister yaoi — romance comics made by women, for women, about romantic trysts between gay men. The marketing logic here is obvious; one hot boy good, two hot boys better.

Over the last decade, imported Japanese comics, or manga, have gained a huge following among young girls in America. One of the most successful, and most startling, genres has been shonen–ai or its more explicit sister yaoi — romance comics made by women, for women, about romantic trysts between gay men. The marketing logic here is obvious; one hot boy good, two hot boys better.

However, many commentators seem uncomfortable with the straight (ahem) prurient motive, and have instead come up with a pseudo-sociological explanation. The argument goes that girls like yaoi because, as children’s book marketing manager J. Ho puts it, “reading a gay romance feels ‘safe’ to them.” Homosexual love, the argument goes, is, for girls, a step removed; by identifying with male characters, girls can enter the story without becoming too vulnerable.

If the point of shonen-ai is to provide the reader with a sense of emotional safety, nobody sent the memo to Korean creator Sooyeon Won. Her shonen-ai manhwa (Korean comics) series Let Dai — which concluded with volume 15 in December 2009 — features cheerful covers with frolicking puppies and pastel tones. The interior, however, is much, much less sunny. The art is, by shojo standards, unfrilly and grim, more likely to show an unflinching close-up of a bloody, beaten face than drifting flowers or pretty clothes. And as for the plot…well, the first volume includes the brutal gang-rape of a sweetly innocent 17-year-old girl named Eunhyung.

The violence here isn’t explicit or exciting; indeed, it’s barely shown. Instead Won simply, and with ruthless compassion, shows us how the tragedy poisons Eunhyung’s existence. Over time, you come not just to pity Eunhyung, but to admire and love her. She finds new friends, tenuously creates a new identity for herself, and seems at last to have regained in her life some sense of joy. (And skip the next paragraph if you don’t like spoilers. Last chance….)

The touch of hope for Euhnyung makes her fate all the more unbearable. Just as she seems to have sorted herself out, and with an entirely lovable and sweet new boyfriend named Naru on the horizon, a jealous “friend” starts telling people in school that Euhnyung was raped. Humiliated, Euhnyung then accidentally overhears a conversation which makes her think (erroneously) that Naru has been stringing her along.

So she runs away, growing increasingly hungry, lonely, desperate, and bitter, until finally she climbs to the top of a building and throws herself off. But she doesn’t die. So, broken bones and all, she drags herself back into the building, back up the stairs, and jumps off again, finally killing herself. This is all told from her point of view, incidentally; you’re in her head while she jumps. It’s an absolutely remorseless sequence; one of the most painful things I’ve read in a comic book. It made me cry like a baby.

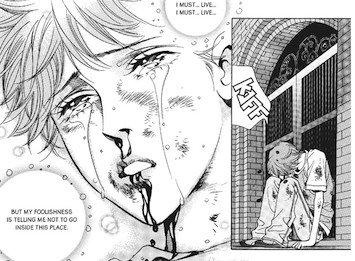

At the center of the book’s brutality, both physical and emotional, is Dai, a high-school gang leader from a wealthy and powerful family. Dai is extremely intelligent, magnetically charismatic…and a sociopath, with neither compassion nor any moral restraint. In a passing moment of pique he allows his hangers-on to rape Eunhyung; he puts classmates and even teachers in the hospital on a whim. Almost as casually, it seems, he falls in love with Jaehee, a younger boy his thugs have been tormenting. In one of their first encounters, Dai has his gang beat Jaehee, then slashes open his own chest with a piece of broken bottle and forces Jaehee to lick up the blood.

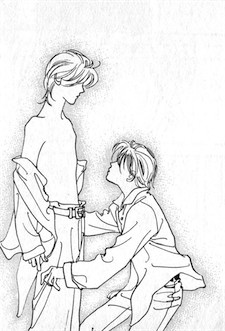

From there, the two move into a classic abusive relationship, with Jaehee desperately clinging to every sign of approval and tenderness and Dai vacillating between romantic savior and jealous, paranoid monster. Dai does reform in the last volume, but it’s not especially believable. Woo is at least canny enough to separate him and Jaehee permanently. It’s one thing to grant your psychotic abuser grace; it’s another thing to live with him.

Yet, while he is never quite convincing as a good person, Dai remains a sympathetic character. In part this is because, like Jaehee, the reader wants to believe in the boy’s glimmers of humanity; in part it’s because Won’s drawings of him are so languidly lovely. Mostly, though, it’s because, while Dai is selfish, he is not, like his corrupt Senator father, a hypocrite. Dai ‘s cynicism is unapologetic and in many ways irrefutable. He’s right that trying to help others is as likely as not to make everyone miserable; he’s right that striving for justice rarely leads to good, or to catharsis, or to anything except more injustice. Dai is only as unfeeling as the world — except that he loves. That love is neither safe nor necessarily good. But it is beautiful.

Yet, while he is never quite convincing as a good person, Dai remains a sympathetic character. In part this is because, like Jaehee, the reader wants to believe in the boy’s glimmers of humanity; in part it’s because Won’s drawings of him are so languidly lovely. Mostly, though, it’s because, while Dai is selfish, he is not, like his corrupt Senator father, a hypocrite. Dai ‘s cynicism is unapologetic and in many ways irrefutable. He’s right that trying to help others is as likely as not to make everyone miserable; he’s right that striving for justice rarely leads to good, or to catharsis, or to anything except more injustice. Dai is only as unfeeling as the world — except that he loves. That love is neither safe nor necessarily good. But it is beautiful.