Round two of the Handmaid v. Watchmen dystopia smackdown. Round 1 is here.

Published within two years of each other, Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale both emerged from a similar cultural anxiety regarding the future of society in an increasingly uncertain and ambiguous world. Although these two works are typically classified under the genre of dystopian literature, I will argue they adhere better to John Huntington’s theory of utopian and anti-utopian literary models. Huntington makes an important distinction between dystopian and anti-utopian literature. Where dystopia essentially reifies the consistencies of utopia by simply replacing positive social models with negative ones, anti-utopian forms actually oppose these consistencies by discovering problems and raising questions and doubts. We see this ambiguity in both works particularly through themes of morality and heroism. In Watchmen and The Handmaid’s Tale, morality has different valences. These works effectively destroy the conventional spectrum of morality by refusing to depict characters as entirely good or evil. Thus, a closer look at the thematic structures of both works problematizes their categorization as dystopian literature, and reveals a greater affinity to the more uncertain and inquisitive anti-utopian model.

First it is important to understand Huntington’s model of utopia/dystopia and what he proposes in response to this binary: the anti-utopia. He says that while utopia and dystopia ostensibly represent opposite models of society, they actually share a common structure: “both are exercises in imagining coherent wholes, in making an idea work, either to lure the reader effectively deconstructs the misconception that dystopia is the ideological and structural opposite of utopia. Although they represent different extremes on the same spectrum, utopia and dystopia are actually aligned in the way they function. Both strive to construct a complete and coherent model of society, relying on the “expression of the deep principles of happiness or unhappiness” (142). By theorizing the notion of anti-utopia, Huntington proposes a new model that more fully opposes the consistencies of utopian/dystopian paradigms. He argues, “If the utopian-dystopian form tends to construct single, fool-proof structures which solve social dilemmas, the anti-utopian form discovers problems, raises questions, and doubts” (142). Accepting Huntington’s revision, dystopian models actually reify the consistencies of utopian models by simply replacing positive structures with negative ones. Thus, the anti-utopia subverts the utopia/dystopia binary by complicating the coherent models they attempt to construct. Although Watchmen and The Handmaid’s Tale are typically categorized as dystopian literature, Huntington’s theory of the anti-utopia is actually more representative of the nuanced and complicated morality that characterizes both works.

Utopian and anti-utopian models both work as a form of social criticism. Every utopia is a criticism of the world as it exists in reality; every anti-utopian model serves to oppose some sort of utopian ideal. Thus, both models are inherently satirical, but to opposing ends. However, Huntington expands the satiric function of anti-utopias. He contends:

Anti-utopia, as I am here defining it, is not simply satiric; it is a mode of relentless inquisition, of restless skeptical exploration of the very articles of faith on which utopias themselves are built. Thus, while there is much anti-utopian satire, it is not an attack on reality but a criticism of human desire and expectation. (142)

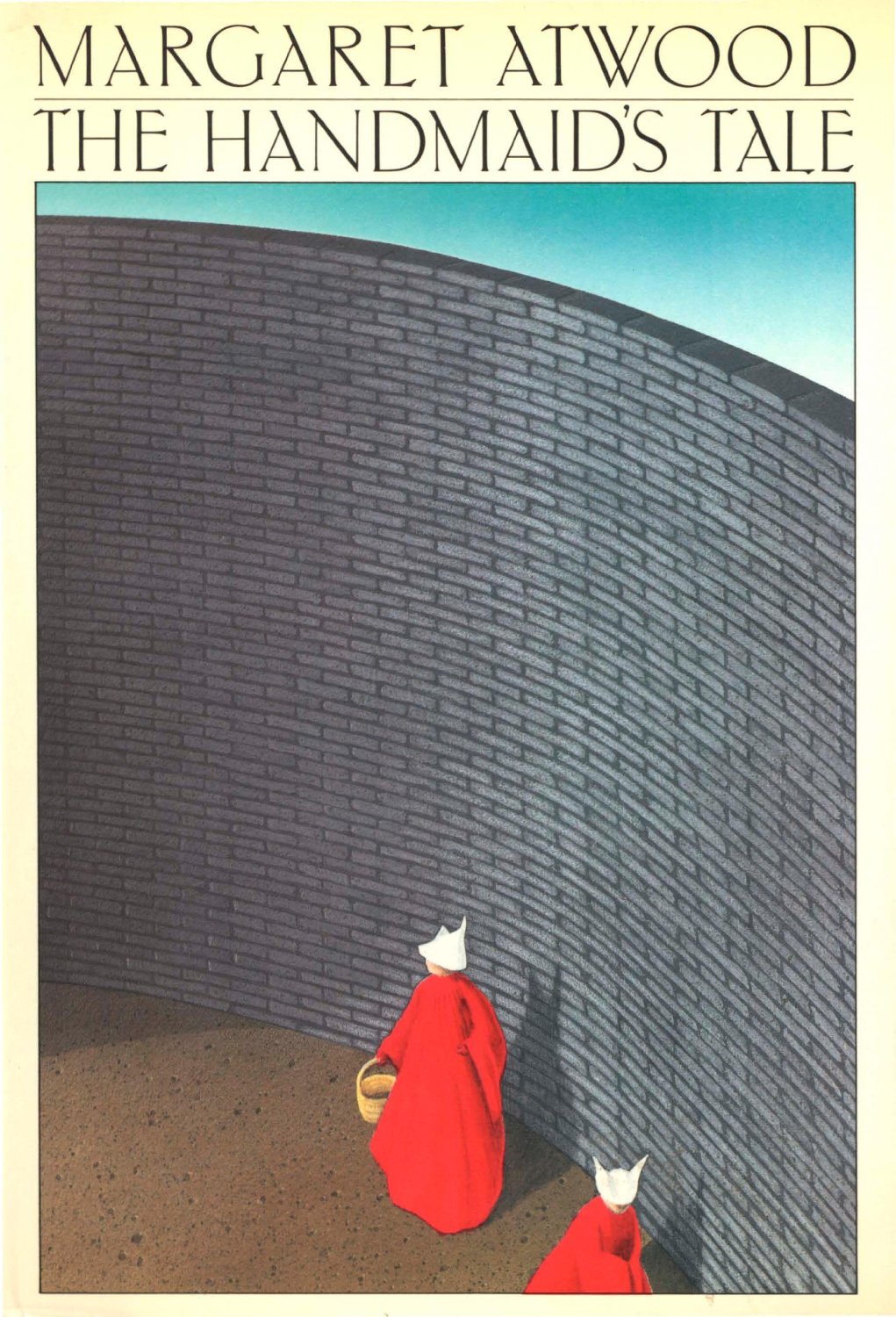

Where utopia seeks to improve or modify some established reality, anti-utopia illuminates the dangers particular human desires. Watchmen and The Handmaid’s Tale work to express the consequences of particular human desires. Atwood explains that while constructing the story of The Handmaid’s Tale she did not make anything up. Everything is derived from some historical precedent. She says, “I did not wish to be accused of dark, twisted inventions, or of misrepresenting the human potential for deplorable.” She continues that the seemingly dystopian elements of The Handmaid’s Tale such as forced reproduction and childbearing, clothing symbolic of castes and classes, and the control of literacy “all had precedents, and many were to be found not in other cultures and religions, but within western society, and within the ‘Christian’ tradition, itself.” The Handmaid’s Tale and Watchmen are both rooted in a very real and rational fear regarding the fate of society. While Atwood responds to the radicalization of conservative politics by creating the world of Gilead, Moore actually contextualizes Watchmen in an exaggerated and dramatized version of American society. In his book Considering Watchmen: Poetry, Property, Politics, Andrew Hoberek notes that Watchmen engages with the politics of the Cold War, arguing that that Reagan administration’s “bellicose rhetoric” and “policy of military buildup” had restored a fear of nuclear war to the US public consciousness (119). The doomsday clock serves as a structural backbone of the text by introducing each chapter with the looming reminder of society’s imminent fate. The Handmaid’s Tale and Watchmen construct anti-utopias that criticize trends in radical human desire that characterize their shared historical context.

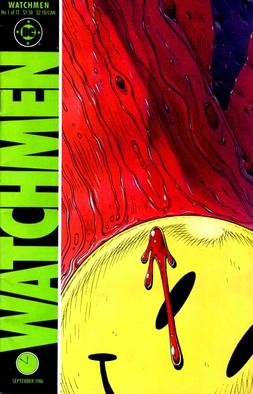

Moore and Atwood destabilize the comforting binaries of utopian and dystopian societies by constructing their fictional worlds in complete moral ambiguity. The superhero context of Watchmen deals explicitly with issues of morality and social justice. Prevailing cultural conceptions of the superhero narrative include a Manichean divide between good and evil: a clear distinction is made between the morally superior superheroes and the degenerate villains. In Watchmen, however, Moore deconstructs this generic expectation by depicting his superhero team as morally flawed and even depraved. Take the Comedian, for instance. A satire of Captain America, the Comedian epitomizes the complete reversal of our expectations of morality. A government pawn, the Comedian embodies the ideals of imperialist United States. However, Moore represents this association as a negative and destructive force. As several of the Watchmen attend the Comedian’s funeral service, Nite Owl reminisces about his days of crime fighting with the Comedian. The imagery of the scene is chaotic and violent as the public has begun to turn against the superheroes. The Comedian and Nite Owl hover above the crowd almost menacingly as people hurl rocks at them.

In several panels the Comedian depicted almost entirely in shadow; along with his mask, he seems to embody the physical tropes of a villain better than a superhero. The Comedian even has his gun drawn on a crowd of civilians and seems to welcome a battle with them. He says to Nite Owl, “My government contacts tell me some new act is being herded through. Until then, we’re society’s only protection. We keep it up as long as we have to.” Nite Owl responds in disbelief, “Protection? Who are we protecting them from?” (Moore 2.17). This scene comes just after a flashback from Dr. Manhattan where is it revealed that the Comedian shot a woman he had impregnated while serving in Vietnam. In these moments, Moore is not unclear but extremely decisive in his depiction of the Comedian as a depraved character. He underscores the irony of this characterization in the final panel of the scene where Nite Owl questions who exactly they protecting society from. Considering the violence from the previous panels, the answer seems obvious to the reader; the Comedian and, perhaps, other Watchmen pose a real threat to the safety of humanity. In this universe, the people who are charged with the protection and surveillance of society are not universally equipped to uphold this responsibility.

Atwood builds a similar sense of uncertainty in the power structures of Gilead. Specifically, Atwood complicates the binary of good and evil by establishing both men and women as oppressors within her anti-utopia. In the article “Haunted by the Handmaid’s Tale,” Atwood speaks to interpretations of the novel as a “feminist dystopia.” She says this term is not strictly accurate: “In a feminist dystopia pure and simple, all of the men would have greater rights than all of the women. It would be a two-layered structure: top layer men, bottom layer women.” She contends Gilead is actually structured like a regular dictatorship, with powerful figures of both sexes at the apex, and then descending levels of power for both men and women.

This complicated dynamic is especially felt through the relationships between female characters in the novel. Offred is frequently oppressed by male and female characters. Ironically it is Aunt Lydia, a woman, who seems to represent the most pervasive and unavoidable oppressive force. Not only does Aunt Lydia survey every movement of Offred and the other women beneath her, she frequently delivers woman-hating rhetoric. After showing the handmaids a 1970s porn film where a woman’s body is being mutilated, Aunt Lydia warns them, “Consider the alternatives . . . you see what things used to be like? This was what they thought of women, then. Her voice trembled with indignation” (Atwood 118).

Although it is clear that the Commander stands at the top of the pyramid of power, Atwood avoids a strictly gendered power hierarchy by creating an overt hostility between women of different castes. In the essay, “Margaret Atwood’s dystopian visions,” Coral Ann Howells suggests that through the Commander’s wife and the odious Aunt figures, Atwood presents a critical analysis of the rise of the New Right and Christian Fundamentalism of the 1980s (169). She continues by saying that Atwood “dispels any singular definition of ‘Woman’ as it emphasizes Atwood’s resistance to reifying slogans, whether patriarchal or feminist” (168). Atwood avoids an overtly feminist tone by depicting her female character from different positions of power and even divergent conceptions of womanhood. Even if women such as Aunt Lydia are just instruments of a more powerful authority, it is significant that Atwood does not use gender as a means to achieve a Manichean divide. She muddies the clear divisions of utopia and dystopia by deconstructing any moral consistencies that align with gender.

Turning back to Watchmen, Moore similarly blurs any obvious divide between good and evil by nuancing his characterization of other superheroes. The character Rorschach exemplifies a moral ambiguity that aligns with Huntington’s theory of inconsistency and doubt in his anti-utopian model. At least initially, Rorschach seems to embody the opposite extreme as the Comedian, an unhealthy commitment to the Manichean dichotomy. In one of the first scenes with Rorschach, the reader witnesses him breaking innocent man’s fingers for simply being uncooperative (Moore 1.16). Rorschach ostensibly opposes the Comedian’s nihilistic view of morality as a futile pursuit. However, Moore deepens his characterization of Rorschach in his conversations with a therapist. Here Rorschach delves into his troubled childhood with an emotionally abusive mother. In one scene the therapist presents Rorschach with a Rorschach test, prompting him to describe what he sees in the image. Rorschach then launches into the gruesome story where he describes butchering the dog of child kidnapper.

He concludes his narrative with the harrowing realization of the inherent evil of all humanity:

Existence is random. Has no pattern save what we imagine after starting at it for too long. No meaning save what we choose to impose. This rudderless world is not shaped by vague metaphysical forces. It is not God who kills the children. Not fate that butchers them or destiny that feeds them to the dogs. It’s us. Only us. Streets stank of fire. The void breathed hard on my heart, turning its illusions to ice, shattering them. Was reborn then, free to scrawl own design on this morally blank world. Was Rorschach. (Moore 5.27)

Here Rorschach mimics a kind of superhero origin story as he reveals the conception of his dangerously rigid moral code. Also embedded within this speech, however, is a moral philosophy that is strikingly similar to Huntington’s argument. Through Rorschach’s perspective, Moore constructs a moral vacuum in the world of the Watchmen, This absence leaves Rorschach to inscribe his own twisted principles onto his surrounding society as he pleases. Rorschach articulates a kind of ambivalence that is integral to Huntington’s model of the anti-utopia. By saying that “existence is random” he implies that there are no moral patterns that drive society; there is “no meaning save what we choose to impose.” Rorschach’s worldview encompasses a sense of discomforting inconsistency. People are not inherently good; they construct their morality according the exigencies of “this morally blank world.” According to Rorschach, morality is always a dubious and contrived design.

The Handmaid’s Tale and Watchmen further adhere to Huntington’s anti-utopia in their vague and uncertain endings. Huntington notes that unlike utopian and dystopian works, the anti-utopia “does not succumb to the satisfactions of solutions” (142). Committed to questioning and raising doubts, the anti-utopia refuses to provide any clear resolution. For instance, in the final scene The Handmaid’s Tale, Offred is escorted from her home by governments officials who accuse her of the “violation of state secrets” (294). Despite the tension of the scene, Offred offers the strangely ambiguous final reflection: “Whether this is my end or a new beginning I have no way of knowing: I have given myself over into the hands of strangers, because it can’t be helped. And so I step up, into darkness within; or else within the light” (295).

Atwood leaves the reader with two conflicting interpretations of the ending of the novel: should we read it as positive or negative? While Offred demonstrates her fear, “I could scream now,” her final words also suggest a sense of relief, she has finally been removed from her position as a handmaid. The ending of Watchmen is equally as ambiguous. Rorschach’s diary had made it into the hands of a newspaper editor and his assistant. The final panel, however, depicts the seemingly incompetent assistance with a ketchup stain on his shirt reaching for the diary. His editor says from outside the panel, “I leave it entirely in your hands” (5.32). Thus, Moore leaves the transmission of Rorschach’s diary in the hands of a very unlikely and even questionable character. The reader cannot be certain that the diary will be published and Veidt’s plan revealed. Both novels refuse to restore balance to society by constructing a coherent and clear solution. Rather, as Dr. Manhattan says, “nothing ever ends” (5.27); Moore and Atwood trap their works within the unending cycle of history and the evolution of society.

Accepting Huntington’s revision of the dystopian/utopian binary, Watchmen and The Handmaid’s Tale demonstrate a closer adherence to his model of the anti-utopia. Both works reject the moral consistencies that characterize dystopian and utopian genres and instead spread their characters across a nuanced spectrum of morality. In Watchmen, Moore inverts the superhero genre by depicting the Watchmen as the real threat to society. Yet he blurs even this distinction by depicting characters such as Rorschach as committed to an overly idealized or rigid code of morality. The hierarchy of morality is similarly deconstructed in The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood rejects the notion of a “feminist dystopia” by creating a hegemonic power that is enacted by both men and women. She does not give the reader the consistency of aligning morality with a particular gender. Furthermore, Atwood and Moore contain their works in the ongoing cycle of inconsistency and doubt by creating ambiguous endings. The anti-utopia epitomizes its commitment to the questioning of utopian models by doubting whether or not society can ever escape the models of its past.

Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. (New York: Anchor Books, 1998).

Atwood, Margaret. “Haunted by The Haidmaid’s Tale.” The Guardian (January 2012).

Hoberek, Andrew. Considering Watchmen: Poetics, Property, and Politics. (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2014.

Howells, Coral Ann. “Margaret Atwood’s dystopian visions: The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake.” The Cambridge Companion to Margaret Atwood. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). 161-175.

Huntington, John. The Logic of Fantasy: H.G. Wells and Science Fiction. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

Moore, Alan and Dave Gibbons. Watchmen. (New York: DC Comics, 1986).