I just watched Meryl Streep’s portrayal of Margaret Thatcher in the recent biopic The Iron Lady on Netflix, and, as the writing was nowhere near equal to Streep’s uncanny performance, my favorite part was when the empowering patriotic-feminist flashbacks and poignant dementia hallucinations were finally over, so I could turn the sound down and play Morrissey’s “Margaret on the Guillotine” over the credits. There was left-wing populism then, populism of the nostalgic anarchist variety, not just peacefully occupying parks but burning tires on the street, fighting police, and occasionally blowing something up. It seems like a long time ago, because it was in fact a long time ago.

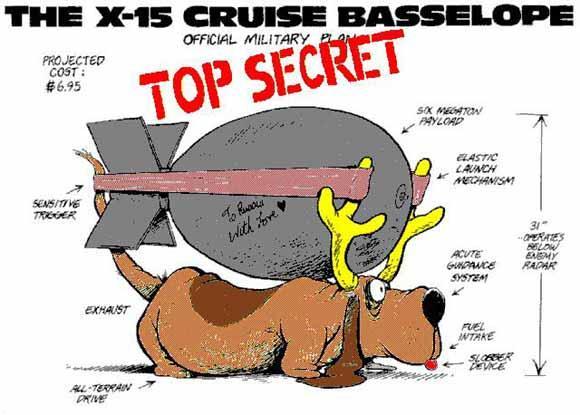

But going back much further, satire and revolution have a curious relationship. Comic theatre and then the first novels appeared in the wake of early-modern wars and catastrophes, mocking the presumed practical piety of those who would consider a proposal, as Thatcher might have had it crossed her desk, to simply eat the Irish. Later, Art Young’s stark cartoon allegories went well with contemporaneous German Expressionist grotesquerie and Brecht’s apocalyptic operettas. And later still, matching roughly the span of the Thatcher era, Berkeley Breathed’s Bloom County documented the denouement of the Cold War from the safe distance of the U.S. One book’s introduction details a Kubrick-esque fantasia when the distance of the Soviets from American soil (American soil in Alaska that is) leads to a national panic. And there is of course the prisoner swap of the re-educated Bill the Cat to the Soviets to get back Opus and Cutter John, along with the memorable inventions of a Basselope-based missile and an air defense shield composed of orbiting money.

The proud modern heritage of satire, whose flame in newspaper comics may have burned most brightly in Breathed, indeed often bases its gags on a safe distance, a safety that renders every attempt at drama absurd—perhaps never less dramatically than in the anxiety closet representing Binkley’s deepest terrors, from which springs forth the unutterable banality of debating economists. But whether it’s the presidential campaign of a catatonic cat, the hunting of a snake that turns out to be the battery cable of a ’73 Pinto, the prescient machinations of junior hacker Oliver Wendell Jones, or even the hijinks of a PMRC-baiting hair-metal band, the silence is deafening, broken up only, as in a spoof of bad stand-up, by the murmur of frogs and crickets.

Irony has become a bad word again. In spite of (or because of) the success of The Daily Show, Buzzfeed, etc., neither committed agitators nor edgy culture-makers want to have anything to do with “funny” art (Paul McCarthy and William Pope L being noteworthy exceptions). But in the 1980s, amidst a brief resurgence of politicized youthful intransigence, there were the Dead Milkmen, the Young Ones, Culturecide, the Crucifucks, Flaming Carrot, Spitting Image, David Wojnarowicz, and Mike Kelley. I had a cheap Casio keyboard and sundry found objects, and my high school friend and I had the temerity to call ourselves a band, and to call that band Nasal Plaque. We mocked the abortion debate, we mocked warmongering, we mocked protest songs, we mocked bluesy authenticity. The treacly hindsight is perhaps neck-deep at this point, but that there was a time when protest was endearingly mean and scruffy, at the same time it was bloody and destructive elsewhere, seems worth a look backward—especially now that the New Republic is claiming that the Onion is “America’s finest Marxist news source,” even while Jacobin is denouncing Adbusters’ crypto-fascist sympathies. Can punk rock, in the end, get over itself?

With full treacly apology, I claim that Bloom County may have been the last great realist comic strip, a salutary deflationary attempt to show the safety pins holding together the tattered corset hiding the hemorrhoids of society. Realists run the risk of being both dismal and arrogant in any such effort; the reluctant realist Ambrose Bierce defined realism in his 1911 Devil’s Dictionary as: “[t]he art of depicting nature as it is seen by toads. The charm suffusing a landscape painted by a mole, or a story written by a measuring-worm.” But in Bloom County of course such humble animals often have speaking roles, stripped of Disneyish innocence and cursed with the anxiety and frustration of a Philip Roth character. Case in point: Portnoy, a frequently angry and bigoted groundhog named after a Roth character, whom Binkley inadvertently clubs senseless in the pointedly unremarkable “Battle of Shady Creek.”

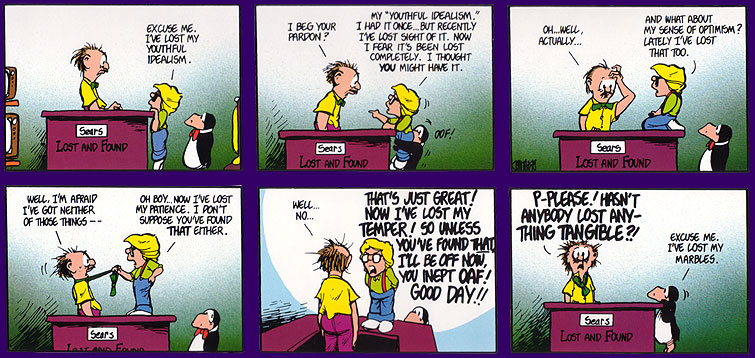

In realist novels, the romantic aspirations of a knight like Don Quixote or a bored housewife like Emma Bovary are revealed as self-destructive neurosis in dense, deadening, deadpan detail, ending inevitably in an arbitrary pathetic whimper rather than a decisive bang of closure, much like when Steve Dallas uses up all the hot shower water (and panel space) singing Julio Iglesias. The non-hero may uncertainly and ironically occupy a macho mise en abyme meta-narrative, as in Joseph Conrad’s mystical Heart of Darkness or Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea; Binkley’s anxiety closet is again Exhibit A, although there’s also the series where Milo is a comics artist being overseen by a hooded executioner, or the Lost and Found counter where Milo demands the return of his lost “youthful idealism” and his “sense of optimism,” ending with the frazzled attendant asking “Hasn’t anyone lost anything tangible?!”

Jane Austen’s characters manage to deflate romance without erasing the stability of social relationships, but social relationships are sometimes the cause of the story’s grim non-resolution in Thomas Hardy, Richard Wright, or The Wire, as in Oliver Wendell Jones’ inevitable confrontation by the authorities (that he sends to Steve Dallas’ house), or by the bugs in his inventions. In Bloom County, a Senator’s blatant corruption or Bill and Opus’ doomed campaign are as humorously bleak as a Sinclair Lewis novel.

When Roland Barthes writes in S/Z about Honore de Balzac’s story “Sarrasine,” he stresses the multivalences and enigmas in this realist tale of wealth and infatuation, and Breathed should similarly get credit for creating an open-ended, unstable stable of characters. Breathed is no royalist, a la Balzac, but neither is he a Theodore-Dreiser-esque socialist realist; his stalwart defenses of “liberals” and “secular humanists” are the subject of many Bloom County strips. Indeed, the political status of a realist art is a sticky matter; the Marxist critic Georg Lukacs stated that the alienation in realism was necessary, praising the effort to depict “totality,” but also that these novels were hardly revolutionary gauntlets. Fair enough. Jed Esty and Colleen Lye say of Mulk Raj Anand that his fiction about India’s poorer castes depicts a “collective subject whose gradual transformation is delineated through pragmatic modes rather than through metanarratives of emancipation.” This reference may seem a trifle high-flown, as well as remote in terms of culture and class, but the cautious optimism of Breathed’s politics certainly dispenses with grand ideals, in favor of a reassuring possibility, once sundry ludicrous delusions are dispensed with, that community might be found among the dandelions.

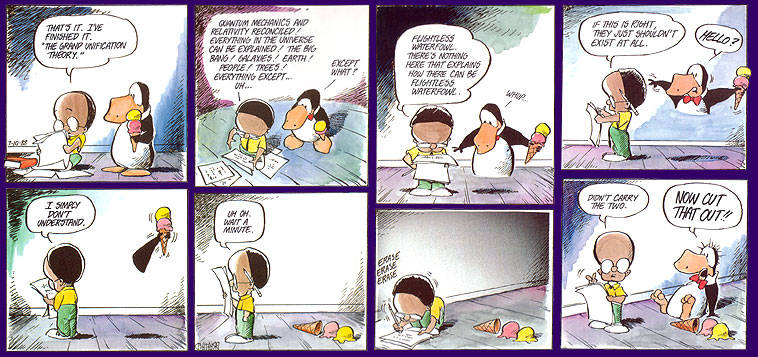

There may be an attempt underway to re-assert political truths in culture, the loss of which Frederic Jameson bemoans in the postmodern replacement of illuminating parodies (like, I claim, Bloom County) by empty pastiche. Recent writings on “speculative realist” philosophy, based in part on the work of one-time French Maoist Alain Badiou, posits an indeterminate infinity of objects beyond conceivability, though this has been critiqued by Alexander Galloway as complicit with the apolitical information infrastructure of late capitalism. I, for my part, appreciate the moment when Oliver Wendell Jones introduces Opus to his “Great Unification Theory,” which explains the entire universe, albeit with the exception of flightless waterfowl. Shouting in panic and clinging to his ice-cream cone, Opus starts to disappear, piece by piece, panel by panel, like Marty McFly in Back to the Future when his future parents are in danger of not falling in love. Finally in the end Oliver figures it out, explaining to the camera, “Forgot to carry the two,” as the reconstituted Opus splutters next to his collapsed dessert. The mathematical absolute itself is lampooned, illustrating that a culture that has sloughed off its illusions finds itself exposed to but perhaps intermittently redeemed by the deformations of a snarky perversity that refuses to die.