In the comics memoir, Sentences: The Life of M.F. Grimm, Percy Carey tells of his experiences growing up in New York, finding success as an emcee in the early 90s, and getting caught up in the drug trade and gang shootings that would eventually leave him paralyzed from the waist down. Artist Ron Wimberly sketches Carey on the graphic novel’s cover in a wheelchair as he is now, rather than surrounded by fans or performing on the stage he once shared with names like Snoop Dogg and Tupac. The choice is fitting, given Carey’s interest in conveying the social and economic realities of his life behind these scenes and after spending time in prison.

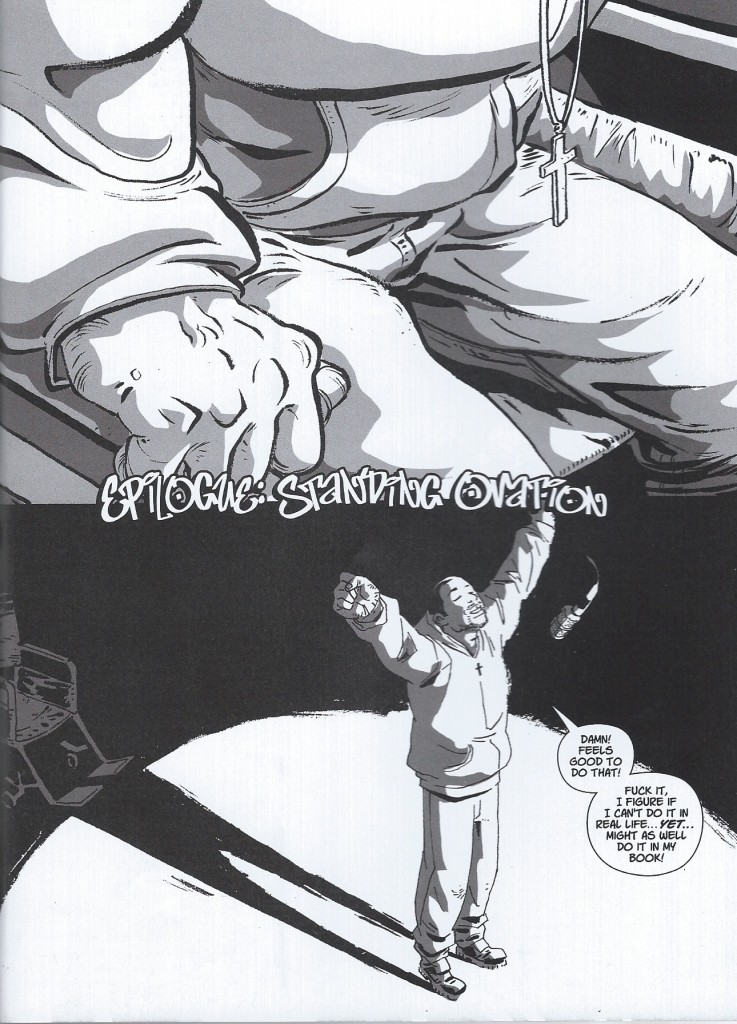

But in the epilogue subtitled “Standing Ovation,” Carey grasps the wheelchair’s arms and pushes himself up. A microphone dangles in the air above him. With his arms stretched out, chin raised, he steps forward and says: “Damn! Feels good to do that! Fuck it, I figure if I can’t do it in real life…yet…might as well do it in my book!”

When we are asked to consider what makes comics unique, I think that our conversation should include scenes like this one. We know that the distinguishing features of comics can extend beyond formal elements to include stylistic practices that develop and advance whenever a sequence of words and pictures tell a story. In this case, Sentences provides an opportunity to talk about what happens when genre conventions refuse to stay put in graphic narratives that are based on actual events.

I’m curious about what Carey’s story accomplishes here by stepping away from what he can’t do “in real life.” Reviews of the comic are unequivocal when it comes to praising his honesty, his unwillingness to glamorize hip hop culture or the drug trade. What, if anything, changes when Carey (in collaboration with Wimberly) frees himself from the wheelchair and in the process, releases his story from the constrictions of nonfiction? By bracketing off the moment in an epilogue, the comic arguably reaches the only kind of happy ending possible without threatening the story’s credibility. At the same time, the utter joy and pleasure that he takes in the visual representation of his body makes the fact that we are dealing with a comic particularly important. Is it enough to say that Carey wishes for the ability to stand or that he imagines what it might be like to walk again when on the concluding pages of his book, he actually does?

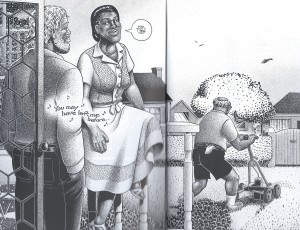

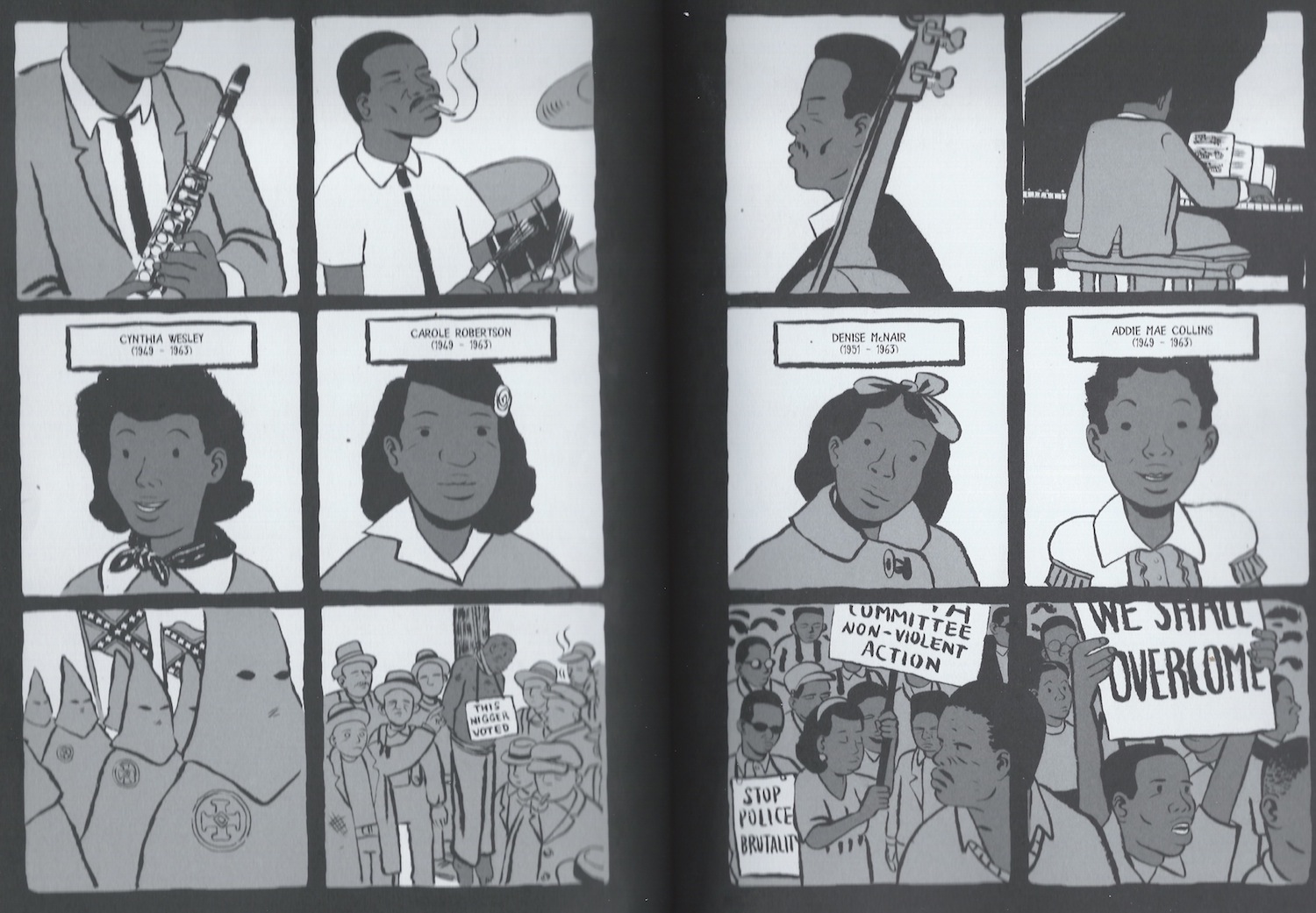

Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby provides a second example. The semi-autobiographical narrative is anchored to the Civil Rights demonstrations of the 1960s, but the comic also breaks away from the “real” in its closing pages. The protagonist, Toland Polk, opens a patio door in the snowy, urban setting of his present and with the sounds of a jazz record curling around the panel, he ushers the viewer into a summer day from his bittersweet Alabama past. As with Percy Carey’s comic book persona, Toland steps out of the story to prepare the reader for this moment. (“There’s something I wanna show you!” he says prior to this page.) The image fills our entire field of vision, maintaining the style and aesthetic features of the rest of the comic in a way that doesn’t merely depict what Toland imagines, but communicates deeper sensations that the viewer experiences within the primary narrative frame.

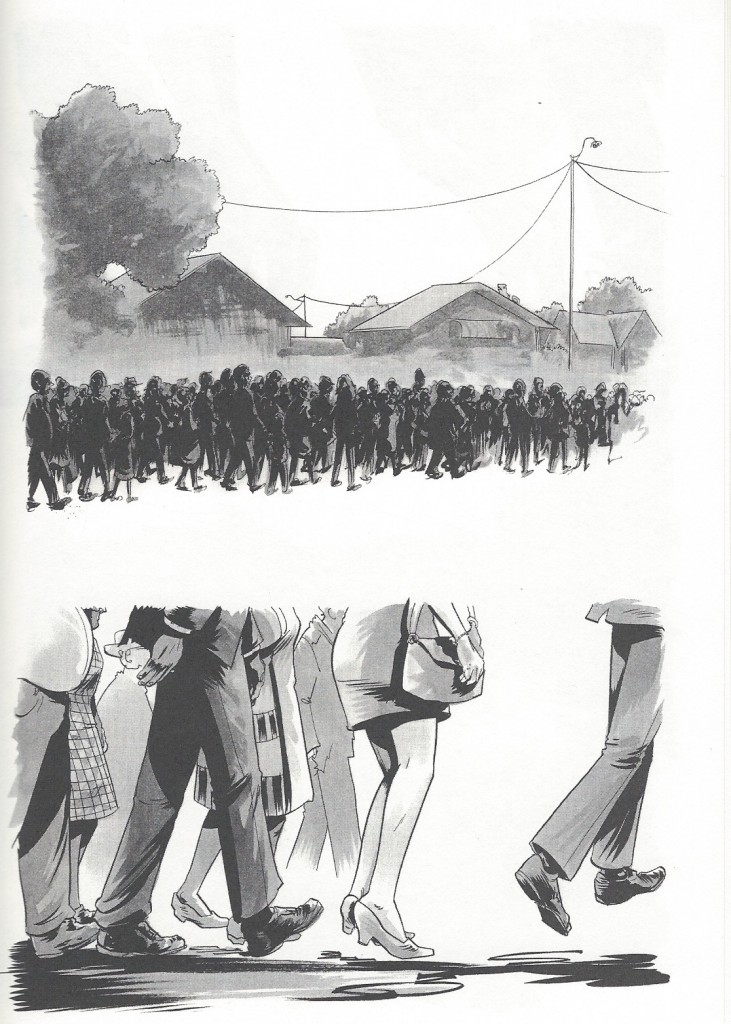

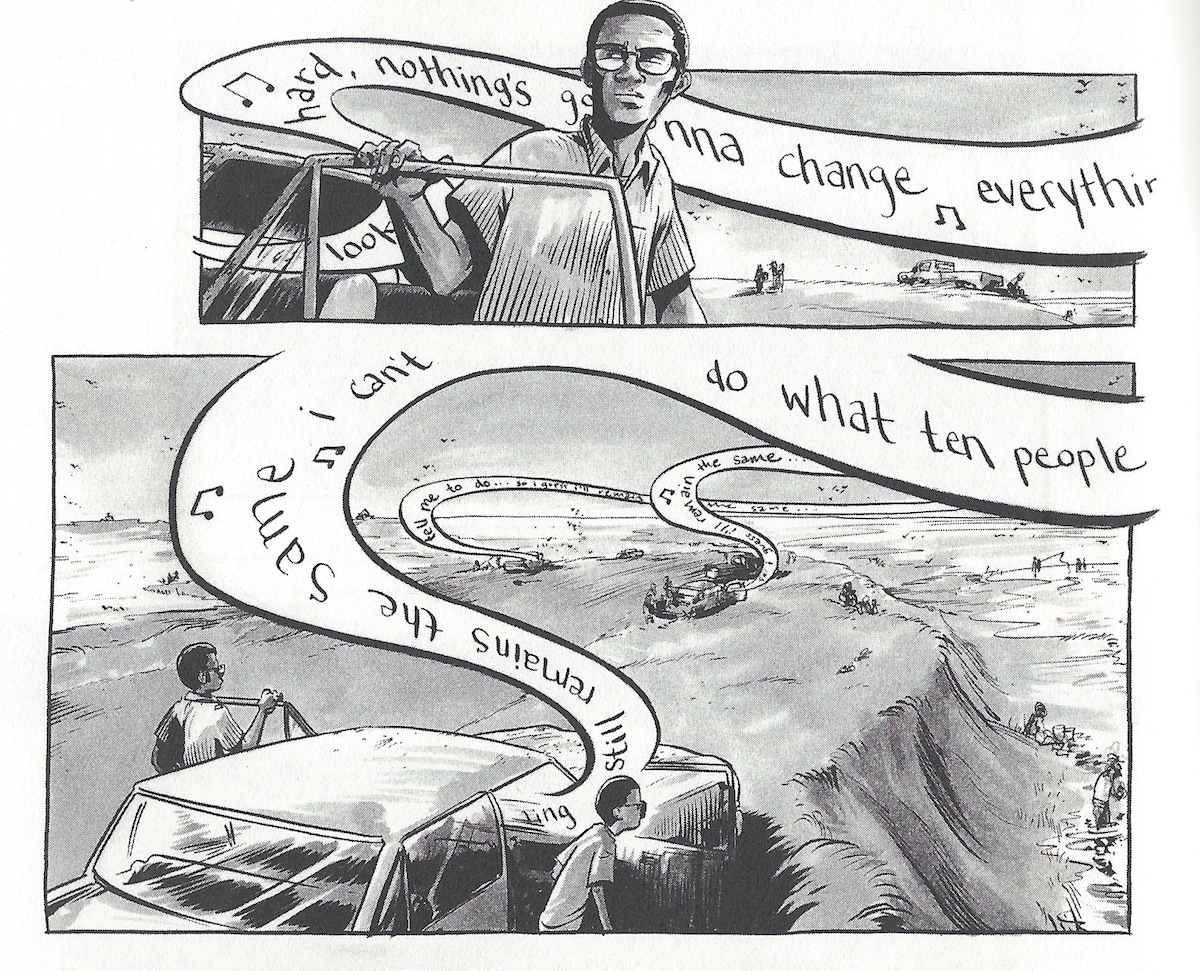

In both examples, dialogue is deployed strategically and in a metafictional way to shape our encounter with realistically-pictured conjecture. But what happens when there are no words to guide us? In my last example from The Silence of Our Friends by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, and Nate Powell, a Civil Rights demonstration ends the graphic novel which focuses on the story of a black and white family involved in the events surrounding a police shooting at Texas Southern University in 1968. The comic is based on the experiences of Long and his father who worked as a television reporter in Houston during this time.

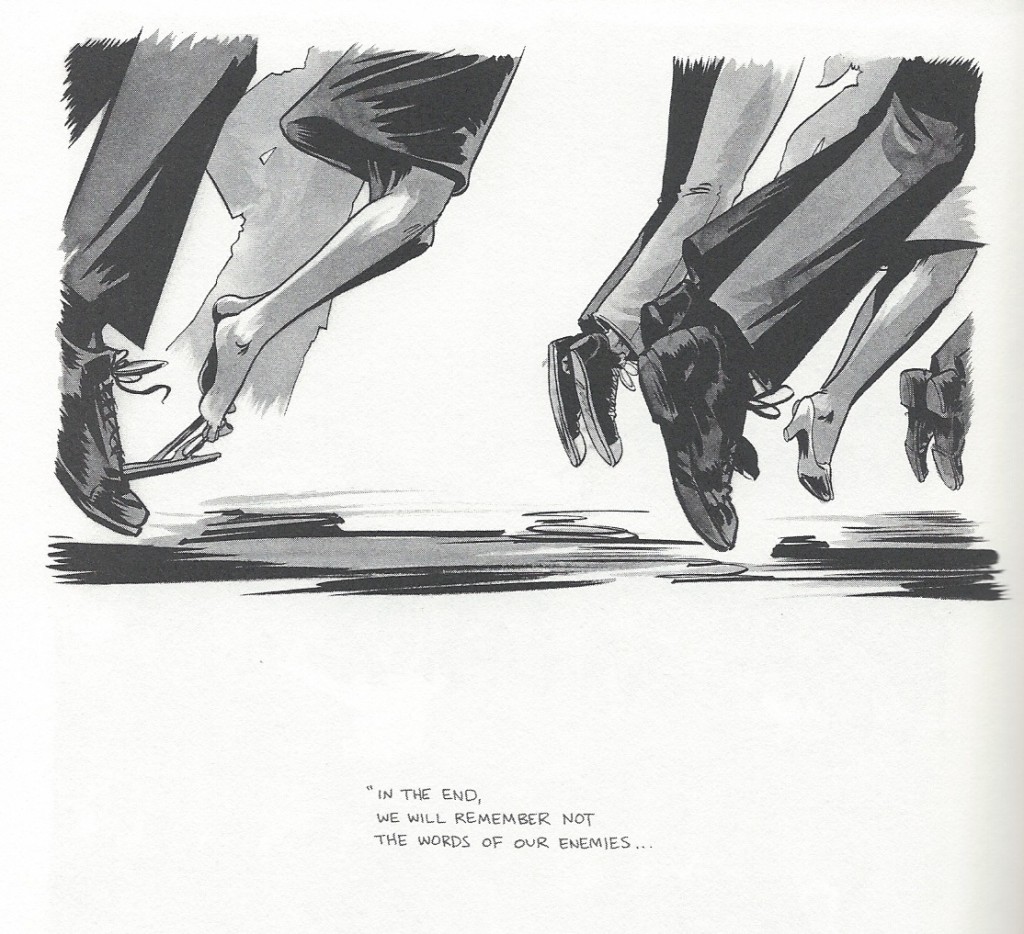

Powell closes the story with a procession of silent marching figures to accompany the Martin Luther King, Jr. quote that serves as the book’s title. The shoes shuffle slowly from panel to panel until they lift without warning and begin to float up. Their flight could be said to signify the protestors’ courage or suggest a longing for social and spiritual transcendence in honor of King’s assassination that year. It could even allude to elements of African myth. Whatever it accomplishes, it does so with no clear verbal signposts, shifting seamlessly into the speculative realm through illustration.

Where do these strange endings leave us? How does this resistance to more realistic representation alter the way we encounter the real in nonfiction comics? Could it indicate an unwillingness to truly face hard, unresolved suffering and social conflict? Or are we so accustomed to comic book flights of fancy that using the tropes more commonly associated with superheroes just feels damn good, to paraphrase Percy Carey, in any type of comic?