We’ve been talking about communism here and there on the blog, so I thought it was a good time to reprint this. It first ran on Splice Today.

____________________

My seven-year-old saw me reading Terry Eagleton’s new book, Why Marx Was Right. Said son has just started reading himself (he loves Jeff Smith’s Bone) and has become perhaps overly inquisitive about any books in reach.

“What’s that?” he demanded. “What’s it about?”

I resorted to that phrase well known to fathers everywhere. “Um….”

“What is it about?”

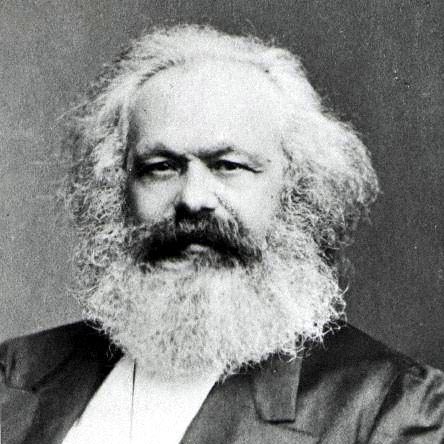

So what the hey, I figured. I’ve explained dinosaurs and gravity and sex. I can explain Marxism. “It’s about somebody named Karl Marx,” I said. “It’s talking about why he was right.”

“Right about what?”

“About not liking capitalism. He didn’t like capitalism.” Blank stare. “Do you know what capitalism is?”

“No.”

“Okay, you know how everybody buys and sells everything?”

“Yeah?”

“That’s capitalism. And Marx didn’t like it.”

An expression halfway between incredulity and boredom. “Why didn’t he like it?”

“Well, with the system where everybody buys and sells and tries to make as much money as they can, you end up with some people who have a lot of money who own the factories, and then some people have only a little money and work in the factories. And Marx thought that was unfair. He said that the people who work in the factories should own the factories.”

“Oh.” Pause for consideration. “That makes sense.”

“Yes,” I said. “But some people really don’t like that idea.”

Then his eyes lit up. “The factory owners don’t like it, I bet!”

So there you have it. Marx’s ideas are intuitive enough that even a seven-year old can understand them. Terry Eagleton would approve.

Why Marx Was Right isn’t quite aimed at the Under 8s, but it is (in a fine old Marxist tradition) a populist polemic. As Eagleton notes, Marx has taken a beating in the last quarter century or so. The Soviet Union has collapsed, China has embraced the almighty yen, and hordes of post-everythingists have laid siege to the university, taunting the academic Marxists for culpable white maleness and general untrendy belief in revolution, sweat, and the physical universe.

Eagleton, however, is undaunted. Marx, he insists, has been buried neither by the corpses of Pol Pot nor by the tomes of cultural studies professors. And certainly neither post-structuralism nor Stalin can boast many apologists with as felicitous a prose style as Eagleton. The books breezes through ten common objections to Marxism, with Eagleton acidly and efficiently dispatching each in turn. To the charge that Marx is a utopian, Eagleton observes:

A virulent form of utopianism has indeed afflicted the modern age, but its name is not Marxism. It is the crazed notion that a single global system known as the free market can impose itself on the most diverse cultures and economies and cure all their ills. The purveyors of this totalitarian fantasy are not to be found hiding scar-faced and sinisterly soft-spoken in underground bunkers like James Bond villains. They are to be seen dining at upmarket Washington restaurants and strolling on Sussex estates.

To the claim that Marx is a simplistic materialist, Eagleton responds in part:

For Marx, our thought takes shape in the process of working on the world, and this is a material necessity determined by our bodily needs. One might claim, then, that thinking itself is a material necessity. Thinking and our bodily drives are closely related…. Consciousness is the result of an interaction between ourselves and our material surroundings.

And so on throughout the book; Marx was a democrat, not a totalitarian; an individualist not a collectivist; a believer in reform and, when that failed, in a revolution that was as little violent as possible. Marxism was feminist before feminism; post-colonialist before post-colonialism, and pro-ecology before most ecologists had befouled their washable diapers.

For those, like me, who haven’t read a lot of Marx, the book is a welcome corrective that goes down surprisingly easily. Sometimes, indeed, too easily. There’s a sense throughout that Eagleton isn’t really engaging Marx’s strongest critics. Instead, the book prefers to incinerate a series of straw men. Thus, Eagleton mentions that Edward Said was anti-Marxist, but he doesn’t quote him, preferring instead to knock down more generalized postcolonialist arguments. Similarly, Eagleton breezily dismisses pacifism with a would-you-use-violence-to-prevent-children-being-shot scenario; some vague references to (never specifically named) just war theory, and a blanket declaration that “In any strict sense of the word, pacifism is grossly immoral.” If you didn’t know anything about debates around pacifism, this might seem like a knockdown effort on Eagleton’s part. Otherwise…well, let’s be kind and say that Eagleton’s discussion is not nearly as convincing as he seems to think it is.

The fact that Eagleton is weak on the thing I happen to know about could just be a coincidence. Somehow I doubt it though. He’s popularizing — which means that this book is less Why Marx Was Right than it is Everything You Thought You Knew About Marx Was Wrong. As such, it’s not likely to bring the revolution, but it might get some undergrads and/or aging reviewers to check out Das Kapital. Who knows? It might even sway the odd seven-year-old.