MELINDA: Hello again, Utilitarians. I’m Melinda Beasi.

MICHELLE: And I’m Michelle Smith.

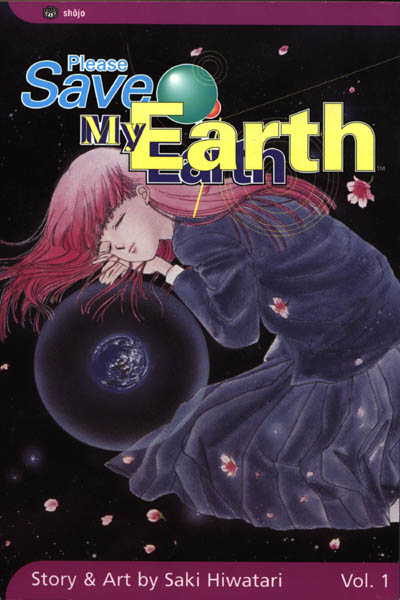

MELINDA: Not long after our debut discussion here on Jeon JinSeok and Han SeungHee’s One Thousand and One Nights, Michelle and I began contemplating a mutual reread of one of my favorite “classic” shoujo series, Saki Hiwatari’s Please Save My Earth, originally serialized from the late ’80s to the early ’90s in Hakusensha’s Hana to Yume and released here by Viz Media between 2003 and 2007. Though our intent was to discuss the series as part of our weekly column, Off the Shelf, we offered it up to Noah first. Shockingly, he said he’d like it, and so here we are!

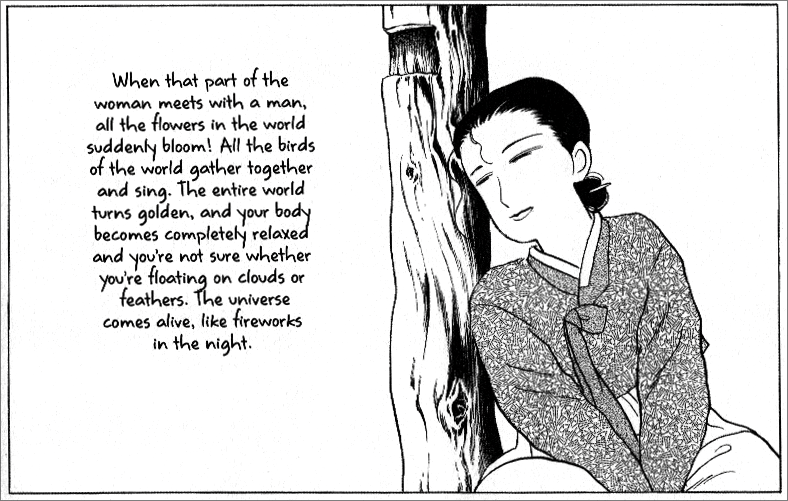

Please Save My Earth is a 21-volume soft sci-fi epic about seven Japanese children (six teenagers and one elementary school student) who discover that they are the reincarnations of a group of alien scientists who once studied the Earth from a remote base on the Moon. Their discovery is made through a series of shared dreams, in which the children re-experience their past lives, including the destruction of their home planet and their eventual deaths from an unknown illness that spread rapidly through the group in their final days. Now reborn on earth, the children seek each other out, burdened with unfinished business from their past lives while simultaneously struggling with the present.

Though attempting to summarize 21 volumes of anything strikes me as a needlessly daunting task, are there any particular points, Michelle, that you feel should be shared up front?

MICHELLE: I’m actually quite impressed that you were able to fit all of that into one paragraph! I would add that the youngest of the children, Rin, has the hardest time coping with his new memories, largely because he didn’t have as distinct a sense of self as the others when awareness of his past was suddenly imposed upon him. Frequently dominated by the personality of Shion, the antisocial engineer he once was, Rin embarks upon a campaign of collecting the others’ passwords—and exacting revenge upon Haruhiko, the reincarnation of the doctor whose vaccine caused Shion to live for nine years after everyone else had died—with the stated goal of destroying the moon base in order to protect the earth.

MELINDA: Perhaps we should mention, too, that Shion went mad during his nine years of solitude, so that’s something Rin is working against as well.

MICHELLE: Which leads us to mention that Shion had a tragic past in which he was repeatedly left behind, first as a war orphan, then after a mere 78 days with the only semblance of family he’d ever known, then by the few people/beings on the homeworld that he actually cared about, and then by his coworkers and especially Mokuren, the “Kiches Sarjalian”—something like a living holy vessel—whom he initially hates and eventually forms a familial bond with in the aftermath of a vengeful sexual attack.

Man, is it ever hard to summarize this series!

MELINDA: I know! So, basically, the guy has epic abandonment issues. It’s not pretty, poor little Rin.

Actually, discussion of Rin leads pretty well into my first order of business. Reading this series for a second time was a profoundly different experience for me than the first. I’m curious to know if it was for you, too.

MICHELLE: Definitely. For one thing, I actually bought this series as it was being released and read the majority of the volumes as I acquired them. This meant that there were actually large gaps between witnessing Shion’s memories of the moon (volumes eight through eleven) and Mokuren’s (fifteen through eighteen), so that when the latter is experiencing anguish over the realization that Shion doesn’t love her, I was pretty surprised. I think I had utterly forgotten about his motivations for assaulting her, an act that he claimed was revenge against the god (Sarjalim) who blessed her with paradise and made his life a living hell.

One thing I didn’t forget, though, was Mokuren’s true personality, which is a lot more feisty and down-to-earth than is suggested by the (carefully cultivated, we later learn) serene countenance she presents to others. I viewed her earlier appearances in the series differently as a result.

Lastly, I think that on the first read I failed to really grasp just how much Mokuren disliked being put upon a pedestal and how important it was for her that Shion saw her as a mere mortal. This time, I see it as one of the most poignant aspects of their relationship, how she wanted to be loved as a woman but he continued to view her as a saint because she forgave him for what he’d done to her.

How was it different for you?

MELINDA: Please Save My Earth was actually one of the first whole series I read when I first got into manga in late 2007, and it was a bit of a revelation in terms of what the medium had to offer specifically to me. As I read, it felt as though someone had entered the brain of my pre-teen self, explored its most beloved, secret crevices, and then put it all down on paper for everyone to read. That’s how deeply I identified with it as an expression of my own fantasy. It had everything my pre-teen imagination most craved—ESP, reincarnation, alien worlds, even age-inappropriate romance—all wrapped up in a pretty, pretty package.

It was an unusually immersive experience, too, since I consumed the whole series over the course of a couple of days. Racing through like that, I was very much plot-focused. Every moment, I was eager to know what would happen next, in the story and with the romantic relationships. I was twelve years old all over again, and I wasn’t about to waste a single moment on unnecessary adult analysis. I had my biases for sure, and I particularly disliked the story’s heroine, Alice (Mokuren), whom I perceived as dull, passive, and maddeningly wishy-washy.

As I began my second read, I fully expected to like the series much, much less. After all, not only had I read a whole lot of (presumably more sophisticated) manga since, I was also a bona fide critic (according to some) with a female-focused eye. Surely any series with a character like Alice at the center was bound to incur my feminist wrath.

Yet, my actual reaction was the opposite. Not only did I experience a complete turnaround on Alice, whose self-reflection and careful contemplation now strikes me as mature and unquestionably smart, but with my lust for plot development out of the way, I was able to spend time thinking about the series’ larger themes, which appeal very much to my grown-up mind. Though I’d still describe the series as “fantastic,” my use of the word has shifted between readings, just about as much as it possibly could have.

MICHELLE: I see some of my own reaction in what you’re saying, particularly because I too thought I might like the series less the second time around and was pleasantly surprised that this did not turn out to be the case. I don’t know that this has anything to do with Please Save My Earth in particular, though. Any time I sit down to revisit a favorite I wonder whether I might be on the verge of tarnishing my original opinion of it. (Which reminds me, I advise against reading PSME‘s sequel!)

Likewise, I also liked Alice a lot more. I had chiefly remembered her as passive, which she admittedly sometimes is, but I forgot that she had just as much capacity for fire and stubbornness as her previous incarnation, Mokuren.

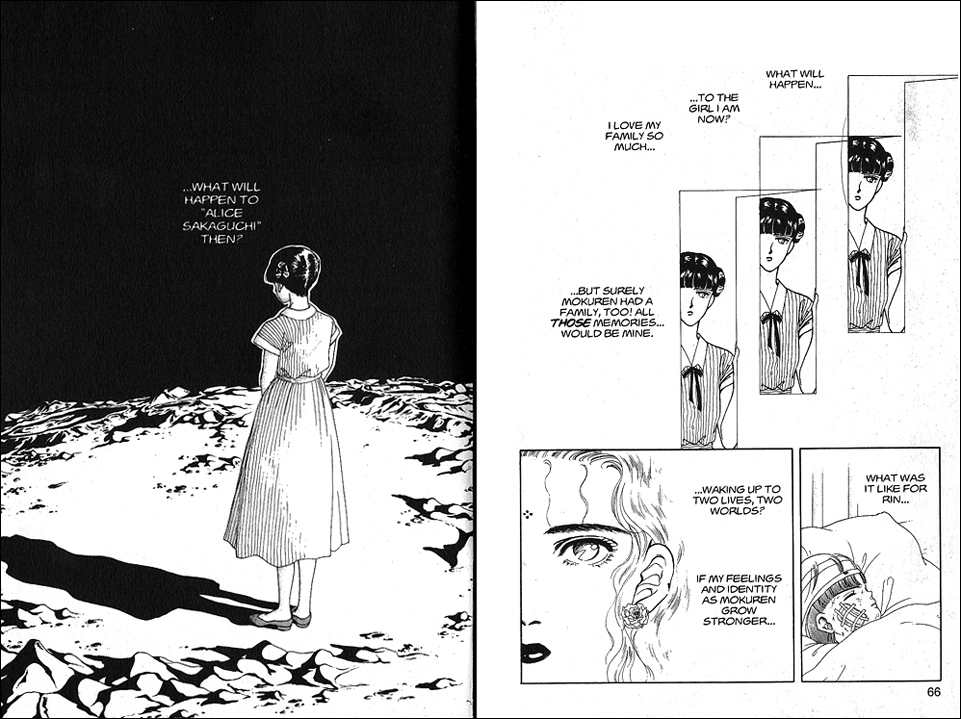

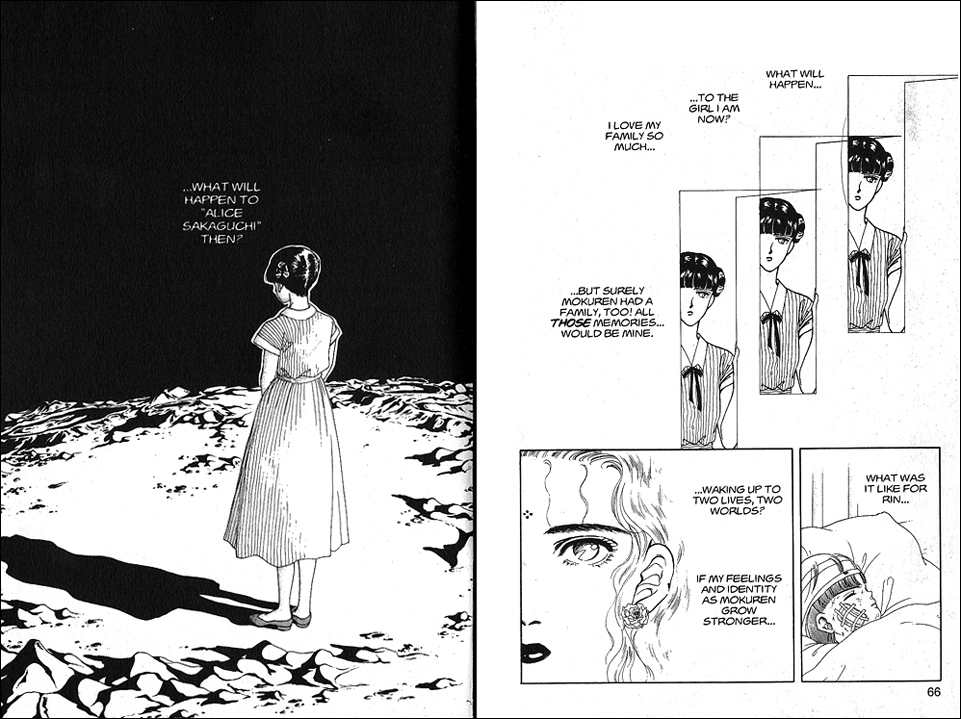

MELINDA: I think what I particularly liked about her on this reread, is that really, she’s the only one of the kids who initially gives any thought to the ramifications of remembering her past life in full. To some extent, the rest don’t have the same opportunity, since most of them began recovering the memories early on, believing them to be ordinary dreams. But even so, once they recognized the dreams for what they were, they jumped into it with (understandable) excitement, not caring much about the consequences. Alice, on the other hand, was immediately concerned about preserving her own identity as Alice Sakaguchi. On this point, she’s not passive at all, and actually much less so than the others, who easily give themselves over to their past selves until it becomes clear that it might be hurting them.

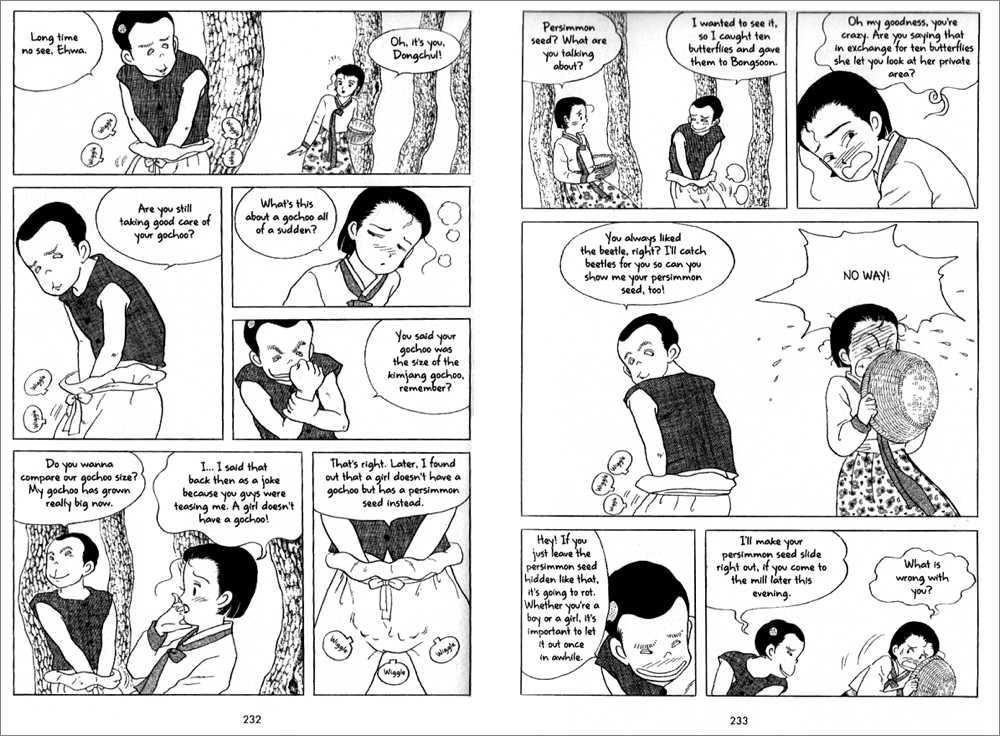

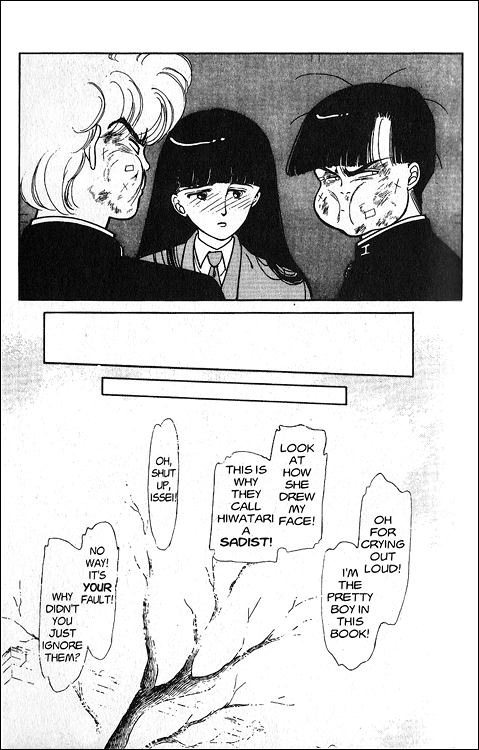

(click image to enlarge)

I know you want to talk about the characters and their relationships, and since we seem to have already started in, wanna make it official?

MICHELLE: Sure. Mostly I was interested in how the present-day characters relate to their past selves, and how those memories shape who they are today. We’ve already talked about Rin, but besides him, Alice and two classmates—Jinpachi Ogura and Issei Nishikiori—are the ones who put the most thought into the situation.

To me, Alice seems to be the character who’s the most distinct from her past life. Alice speaks of Mokuren in the third person, for example, and perceives her as someone who’s encouraging her to move on with her life as she wishes to live it.

Jinpachi is the reincarnation of Gyokuran, an idealistic and impulsive type, and is perhaps the most like his former self. Jinpachi often frustrated me because his opinion on whether to delve into his past life frequently fluctuated, from wanting to confirm it really happened, to being convinced they ought to just forget about it entirely. As Saki Hiwatari puts it, “Jinpachi is easily affected by the mood of the moment.”

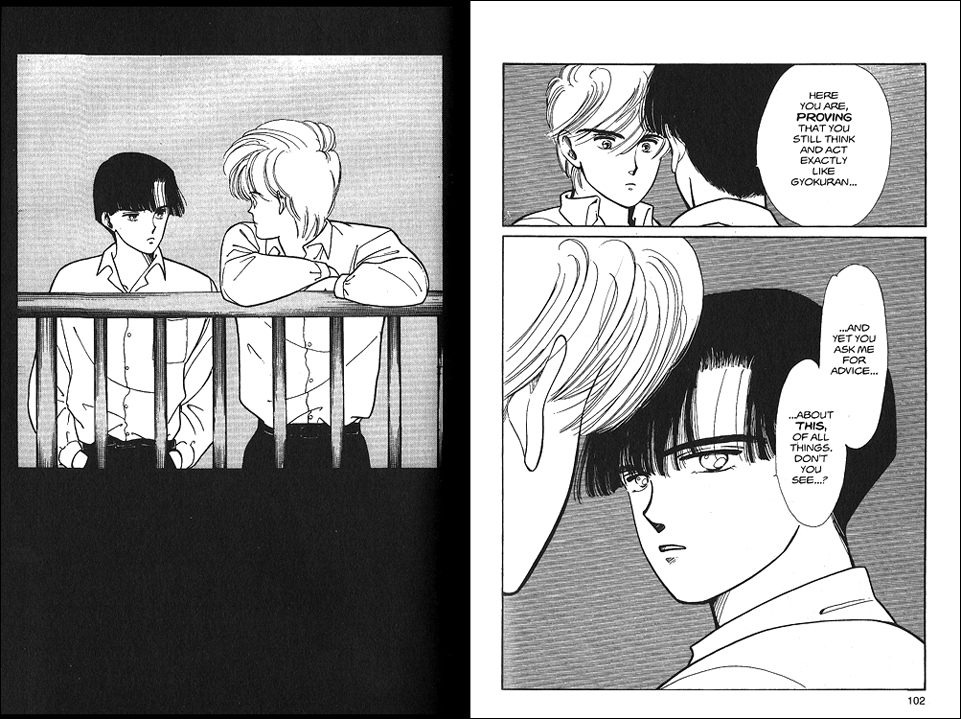

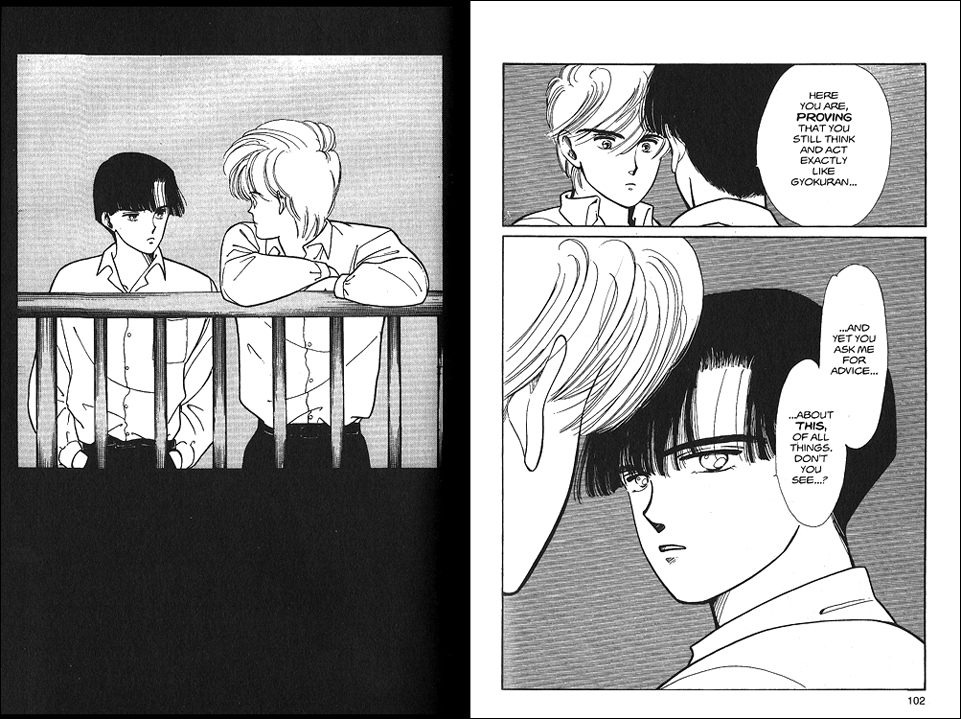

Jinpachi’s close friend Issei is the reincarnation of Enju, a woman who was once in love with Gyokuran. He struggles a lot with her feelings, which ultimately cause him to fall in love with Jinpachi. Eventually he realizes that Enju wanted to come back as a man so she could remain by Gyokuran’s side and yet pursue a new love. Even though Issei is the one who places the ad that brings the group together, he soon decides that perhaps it would be better to put the past behind them.

The other three all began having dreams long before connecting with Alice and friends, so we never see them talk too much about the wisdom of recalling them, though Rin scathingly points out that Daisuke, the reincarnation of mission leader Hiiragi, is only interested in remembering the pleasant times.

MELINDA: While it’s true that we don’t get to see the others thinking or talking about the wisdom of recalling their dreams, we do see them get excited about meeting each other, putting together a full timeline of events on the Moon, and reminiscing with vigor, especially early on. Even Jinpachi, who claims at times that he wants to just put it all behind him, gets swept up in the moment, as you say, even jumping to blame their current incarnations for the actions of their past selves, as though they were exactly the same people. His reluctance to forgive whomever he believes is Shion (this changes midway through) for Shion’s past sins particularly comes to mind.

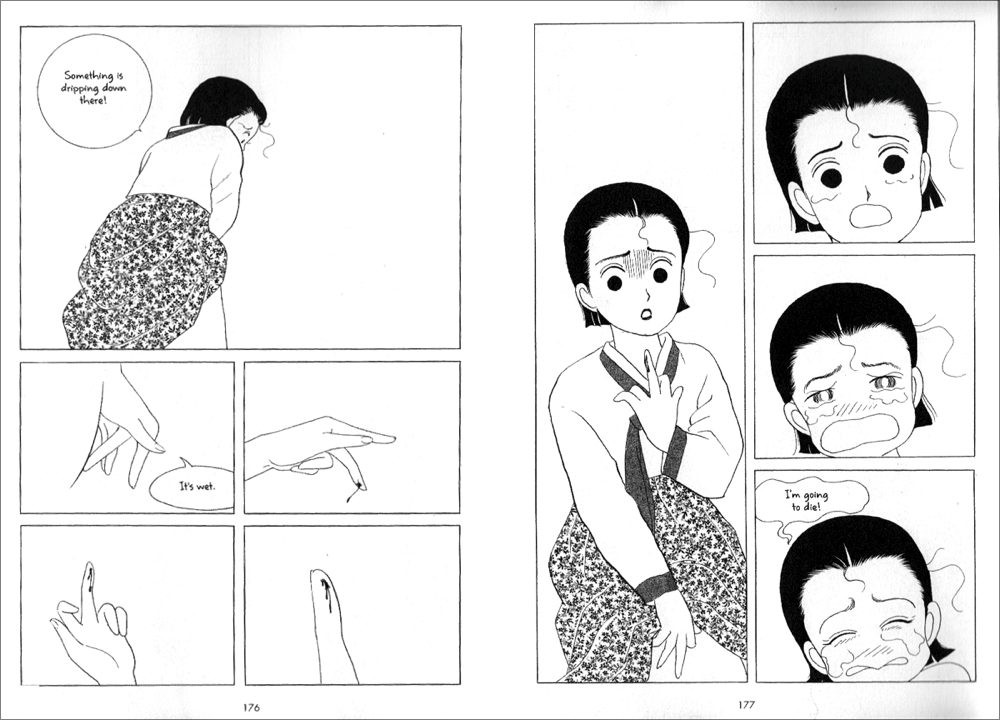

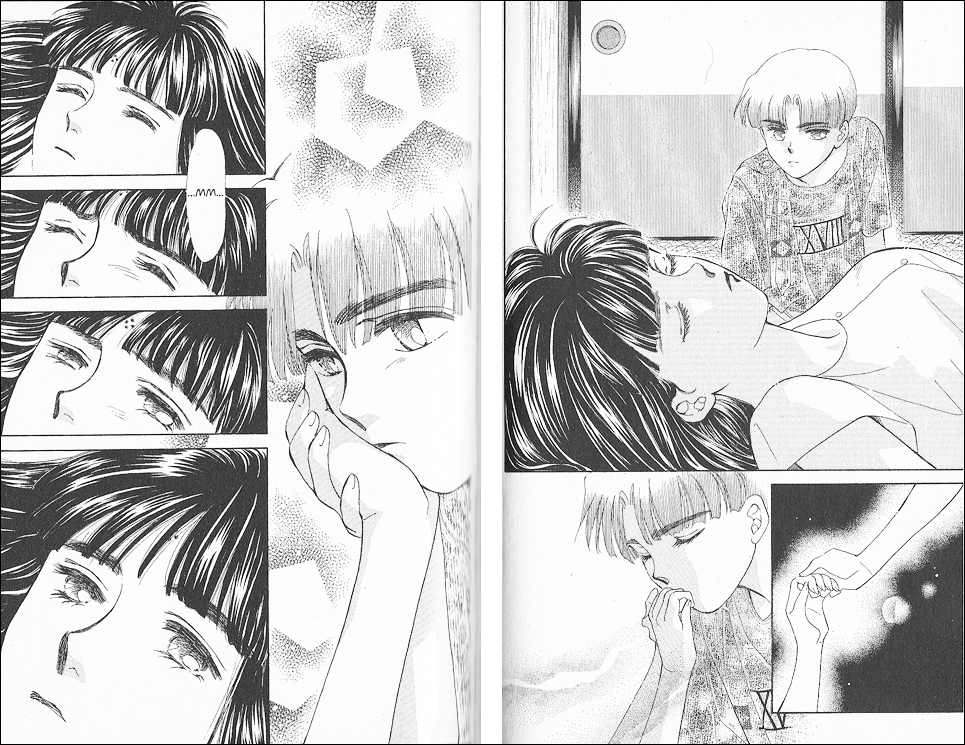

Issei (Enju) is one of the story’s most compelling characters for me, possibly because he’s the first to realize that the memories of his past life have the power to cause him real pain in the present, thanks to his feelings for Jinpachi. When we (and Alice) first meet Issei and Jinpachi, the two are discussing, rather intimately, a sexual encounter between their past selves in the previous night’s dream. The scene between them is downright tender, and it’s painful for us, too, to watch Issei’s feelings for Jinpachi grow stronger while Jinpachi latches on to Alice (Mokuren), creating exactly the same scenario for Issei in this lifetime as Enju was forced to live with during hers, made worse at least initially by Issei’s gender, since it makes the object of his affection even less attainable.

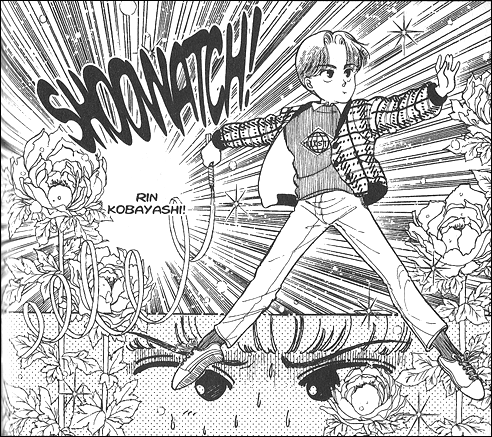

(click images to enlarge)

Though it’s Rin’s story where this becomes most vital, Issei and Jinpachi, too, are forced to really think about the meaning of rebirth, one of the story’s primary themes. Are they doomed to live the same lives over and over again, or is does each new birth give them the opportunity to grow? Though this question isn’t new, by any means, Hiwatari asks it so poignantly throughout the series’ 21 volumes, her conclusions actually feel like revelations, even for non-religious types like me.

MICHELLE: You can’t see me, but I have been nodding throughout your response (especially as pertains to Issei). Am I the only one who found it a little creepy that many of the characters started to use current/moon names interchangeably? Again, I think Alice is the only one who refrains from this practice entirely—possibly because, as her memories were slow to reveal themselves, she initially kept her distance from the others in the belief that she wasn’t really Mokuren.

Related to rebirth, ideas regarding identity also come into play with Mokuren and her feelings about her status as a Kiches Sarjalian. It’s not something she asked for—actually, it’s something she actively wants to be rid of!—and it colors her interactions with others, causing them to make assumptions about her and view her as some perfect, divine creature. Subsequently, men worship her and women ostracize her. She longs to be seen for herself, and it’s not until she meets grumpy, unkind Shion that she finds someone who seems to be talking to directly to her and is not afraid to criticize or desire her.

In fact, maybe it’s this intense desire of Mokuren’s to really be herself that, in an ironic way, fuels Alice’s measured approach to safeguarding her own identity.

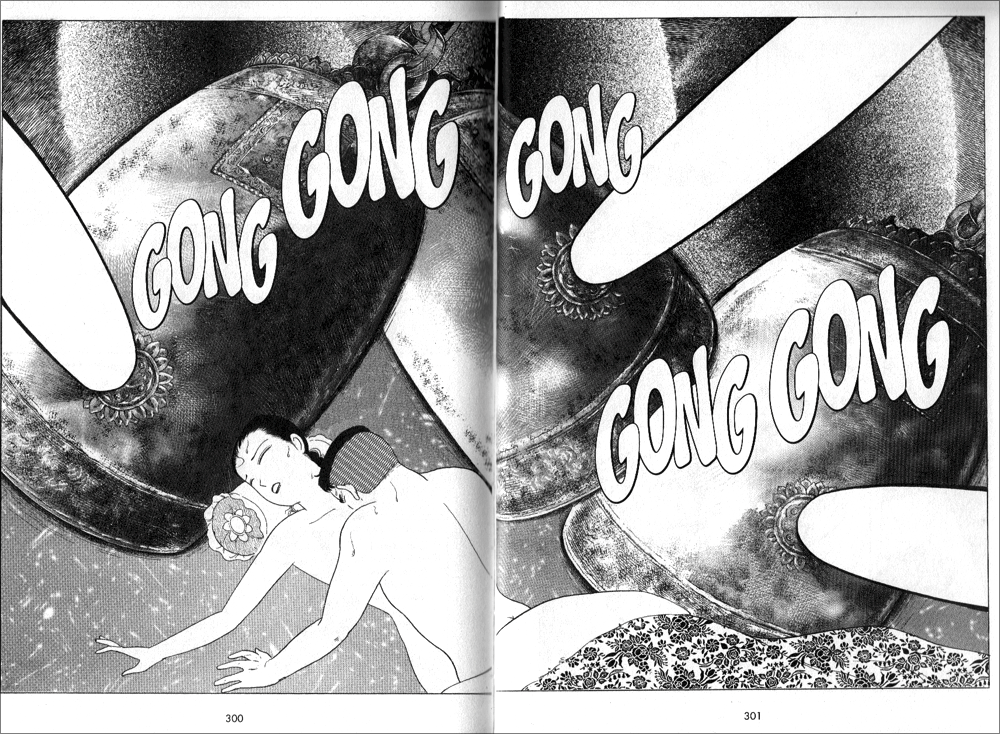

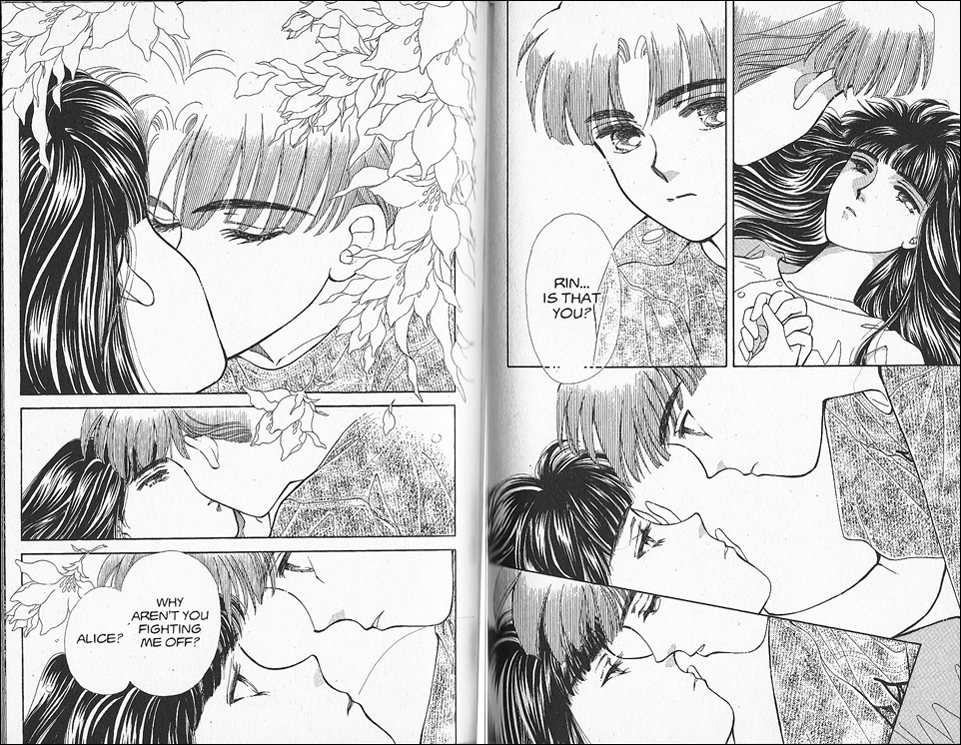

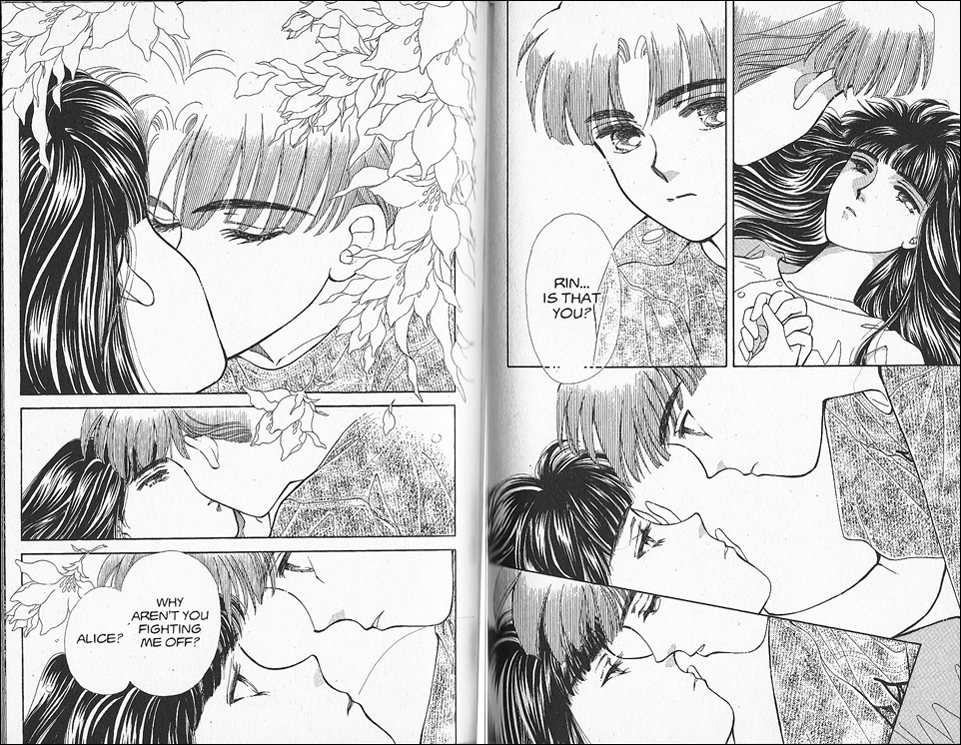

MELINDA: I feel like we probably need to explain more about the whole Kiches business and the religious beliefs of the alien characters, but before we get too far away from discussing the children, let’s talk a bit about Alice and Rin. I mean, here’s a series featuring a bona fide romance between an eight-year-old and a high school student, admittedly pretty chaste, but still, it’s definitely there. And furthermore, Hiwatari somehow manages to pull it off without being creepy. I find this pretty fascinating.

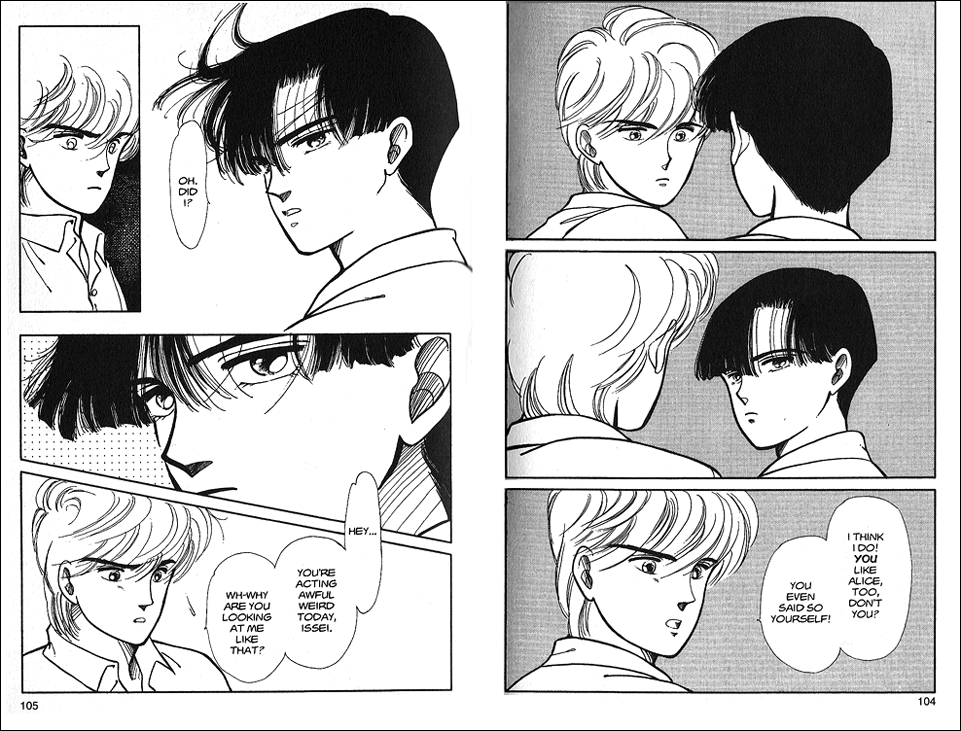

MICHELLE: It is. I found their kiss in volume twenty (initiated by Rin, I note) to be quite striking. “How on Earth am I finding this kind of romantic?” I wondered to myself, as I kept rereading those pages. Possibly it helps that Rin looks so durn grown-up in those panels, but I believe one of the first things Alice does afterward is lament the loss of his childhood.

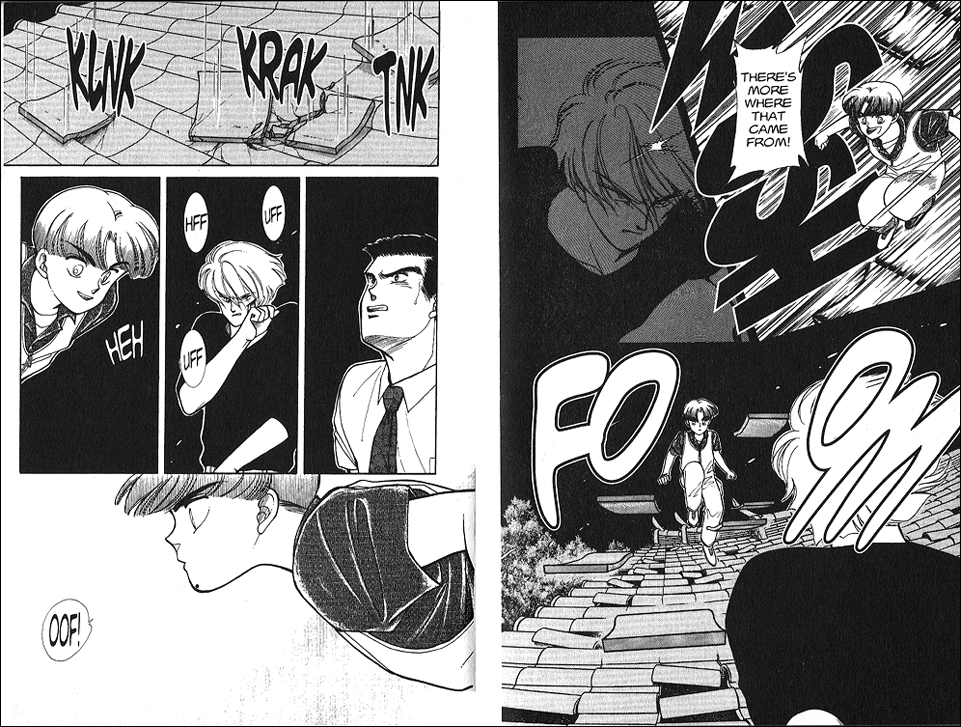

(click images to enlarge)

MELINDA: Honestly, in retrospect, I even found their whole, ridiculous engagement romantic! It’s the kind of thing that would normally only be worked into some bleak period piece, where the poor young woman is betrothed by her family to a little boy for political gain or the like. Here, it’s clearly ridiculous, everyone involved in the situation thinks it’s ridiculous, and yet it ends up being genuinely romantic. How does that happen?

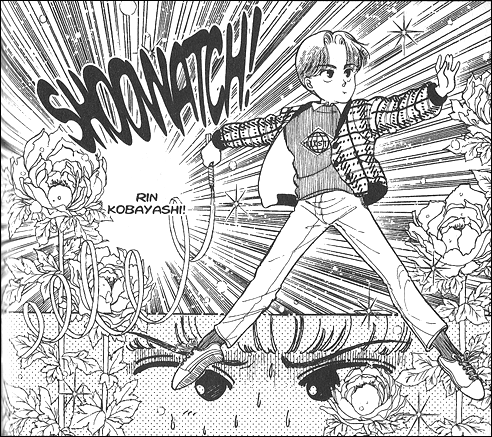

Rin’s journey from annoying little rhythmic gymnast (what a funny little character note that was, I thought) to cold-hearted villain, and finally to romantic hero is one of the quirkiest character arcs I’ve seen, even in shoujo manga, yet it works surprisingly well.

MICHELLE: It was amusing to read some of Hiwatari’s sidebars about the characters and their popularity, because I’m pretty sure fans didn’t like Rin at first, but once they knew of his angsty background, everyone felt so much sympathy for him that they redirected their dislike toward Haruhiko, the boy Rin was browbeating because of what he (Haruhiko) had done in his previous life! I guess a sad backstory can excuse just about anything.

MELINDA: I think if Rin wasn’t so very young and lost under Shion’s influence, his treatment of Haruhiko wouldn’t be so easy to dismiss, but I definitely see your point. Readers do love a tragic backstory. Poor Haruhiko really gets the shaft here! Having been intimidated by Rin into pretending to be the reincarnation of Shion, he’s treated suspiciously by all the others who thought Shion was a dick. Then, by the time it’s revealed that he was actually Shukaido, Rin’s already stolen all the glory away anyway. Shukaido was kind of a smarmy guy, so it’s easy to shrug off his pain, but poor Haruhiko is the one paying the price!

MICHELLE: Yeah, I felt like he kind of got short shrift in the personality department. It’s true that Shukaido wasn’t the most riveting person to be around—mostly I remember him being described as “polite”—but Haruhiko doesn’t move beyond this too much, probably because he spends most of his time either being victimized or suffering with his fragile health. Some elements of a playful personality surfaced near the end, once he had finally confessed his true identity to the others, but we really didn’t get to know him that well, despite how often he appears.

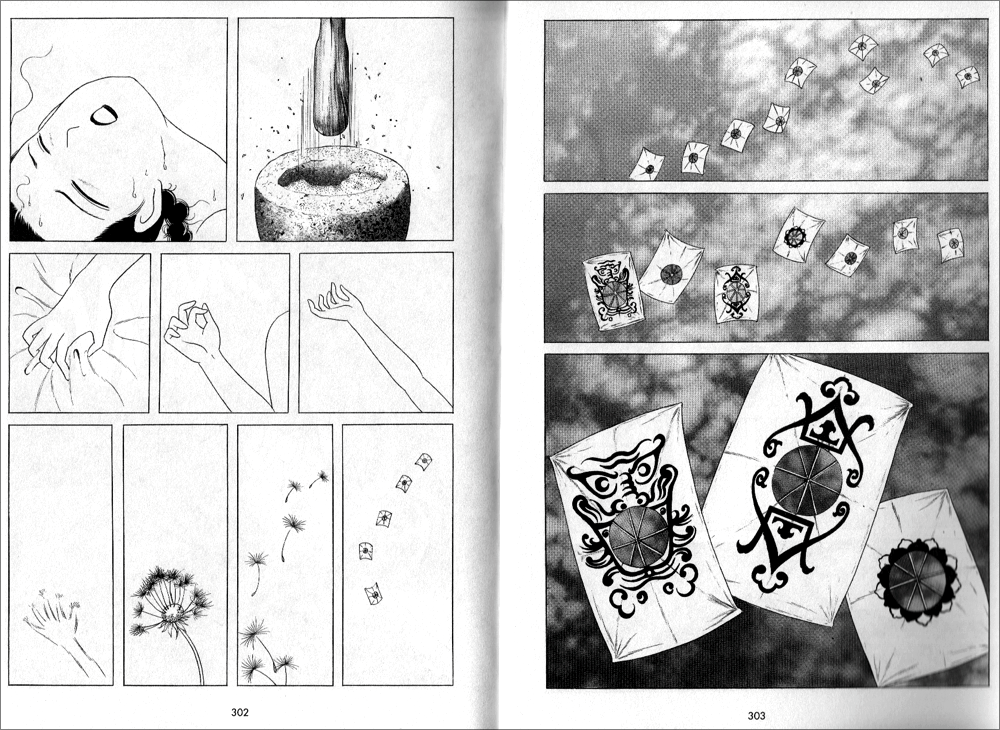

MELINDA: Speaking of tragic backstories, one that I find interesting is Mokuren’s, partly because she works so hard to keep it to herself. Despite her raucous behavior as a child and teenager in “Paradise,” her adult self really strives to behave as a proper Kiches, even though she hates everything that stands for.

Her story strikes a chord with me, probably at least in part because I have an issue with the moral responsibility people like to attach to the “god-given gift,” an insidious concept that plagues our world just as it does Mokuren’s, if not quite as openly. Here’s a little girl, born with a gift granted to very few, forcibly separated from her family for the good of their world, even though neither she nor her parents believe that their parting is for the greater good. All she wants to do is get rid of her “gift,” a wish she’s told over and over again is a blasphemy against god.

Later, when Rin (possessed by Shion) wants to use Mokuren’s power as a way to deceive humankind into fearing god for their own good, it’s obvious that Hiwatari is making a case against that kind of use for religion, but how she really feels about Mokuren’s supposedly divine gift is less clear to me. Personally, I’d like to take away an anti-religious message from the whole thing, but I suspect that’s wishful thinking. What’s your take on this?

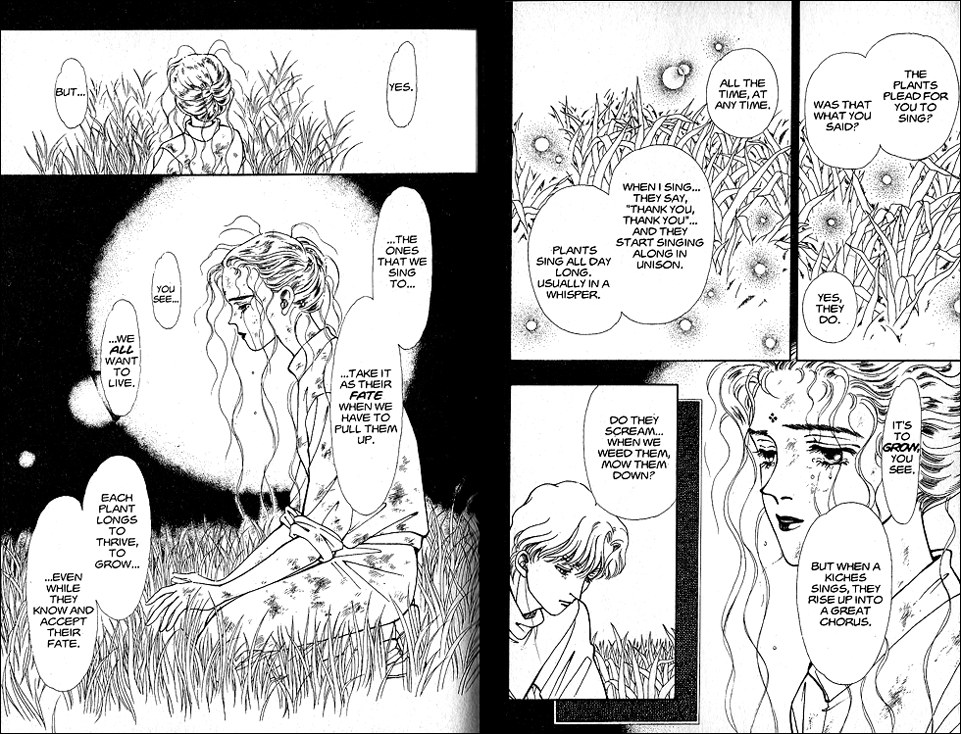

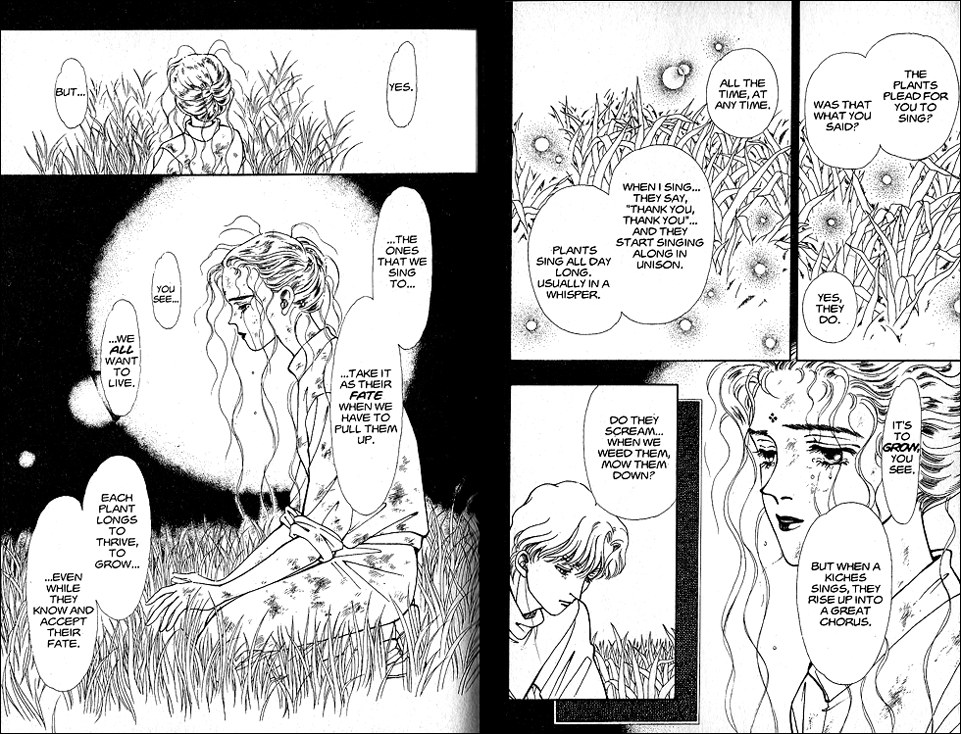

MICHELLE: One thing I want to point out is that, even though Mokuren theoretically has this awesome gift, there is actually very little she can do aside from encourage plants to grow. Much is made that, essentially, all a Kiches Sarjalian can do is cry and sing. Twice in her life—with her first love Sev Oru, who expects her to safe his dying father’s life, and later with a frantic Gyokuran, who implores her to save their annihilated homeworld—Mokuren has come face to face with someone who expects a miracle from her that she is simply no better equipped to provide than your average person. I think that says a lot about religious figures who are treated with reverence—they’re really just people, y’all.

I don’t believe Hiwatari is propounding a staunchly anti-religious message—there are, after all, kind people serving Sarjalim, like the elder who loves Mokuren for her spirit, or the kindly Lian (a sort of nun, I think) who watches over Shion. Still, she seems very critical of this sort of State-controlled religion, which shows no compunction in ripping a three-year-old from her parents’ arms, attempting to squash her dreams (Mokuren must fight very hard to be allowed on the team), or ordering other subjects around on a whim (like Shion, who is involuntarily appointed to the team to lend it prestige). Perhaps what Hiwatari objects to most is the lack of personal freedom that some religions enforce.

MELINDA: Speaking of the religious characters, one of my favorites is Mokuren’s guardian in Paradise, Mode. Though she’s lost her parents, it’s Mode whom Mokuren calls out for in her deepest moments of pain, and I have this secret thought about Alice’s devoted brother Hajime being Mode’s reincarnation on Earth. That might be way off base, but I love Mode and Hajime with similar verve.

MICHELLE: I was going to mention exactly that! I am 300% with you on Hajime being Mode, and I think we are correct. Consider the evidence:

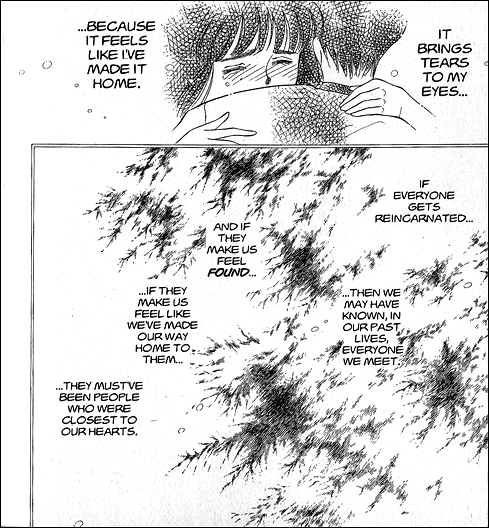

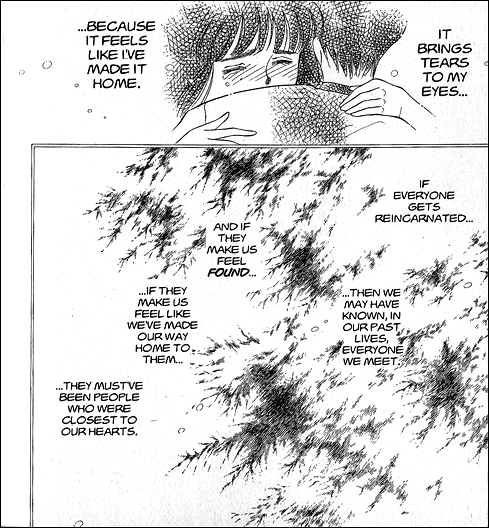

1) In volume sixteen, page 119, Alice is dreaming of Mokuren while the latter recalls bidding farewell to Mode. “Mode… Mode… I loved you so much. I miss you.” When one turns the page, the “I miss you…” is repeated, but this time over an image of Hajime’s concerned face.

2) In volume seventeen, page 166. Alice is embracing Hajime while thinking, “If everyone gets reincarnated then we may have known, in our past lives, everyone we meet. And if they make us feel found… if they make us feel like we’ve made our way home to them… they must’ve been people who were closest to our hearts.”

3) In the epilogue, Sakura suggests that Ayumi, Rin’s former classmate, was first interested in Rin and is now fixated on Jinpachi because she is the reincarnation of Coco, a girl who went from fancying Shion to dating Gyokuran back on the homeworld. If such a minor character can be reincarnated, why not someone as important as Mode?

In fact, I’ll go you one step further and suggest that Boone, the empathic bum who takes care of Rin when he runs away from home, is actually the reincarnation of La Zlo, the “pretend” father Shion lived with for those 78 happy days. He even espouses a similar philosophy, telling Alice that he wants Rin to be “the best at being happy.”

MELINDA: Yes, I absolutely agree! Boone seems to have an immediate affinity for Rin—one that he does not fully understand himself, as though he was meant to watch after him. It’s really quite touching, especially juxtaposed against Rin’s actual behavior while he’s being cared for by Boone, which contains some of Rin’s lowest, most Shion-dominated moments.

MICHELLE: But for all his bad behavior, I’m still so happy for Shion that he gets to have all these people who care about him in this life. He has two parents who spoil him, Alice to love, and various others who merely want him to be happy. I can see why he has such trouble convincing himself that this new life is real, and why his insanity might compel him to try to control the world in an effort to obliterate war and finally be able to relax into his new life.

MELINDA: Speaking of Shion’s master plan, while looking for anti-religion message in this series may be far-fetched, its anti-war message is loud and clear. This isn’t unusual for manga in the slightest, but I appreciate the way Hiwatari makes her point. Using Shion’s pain and desperation, she makes her case against war, while also making it clear that theocracy and government manipulation is not an acceptable or effective way to prevent it. For all the praise heaped on Sarjalim, her world’s devotion was not sufficient to save it from war and destruction, multiple times, ultimately leaving Shion to suffer as the last of his kind.

MICHELLE: Not only that, the people of Shia were often the instigators of war, conquering the inhabitants of nearby planets and moons and colonizing their worlds. For all the reverence bestowed upon the peaceful, nature-loving Kiches Sarjalians by the general populace, those in power don’t seem to have shared the same values.

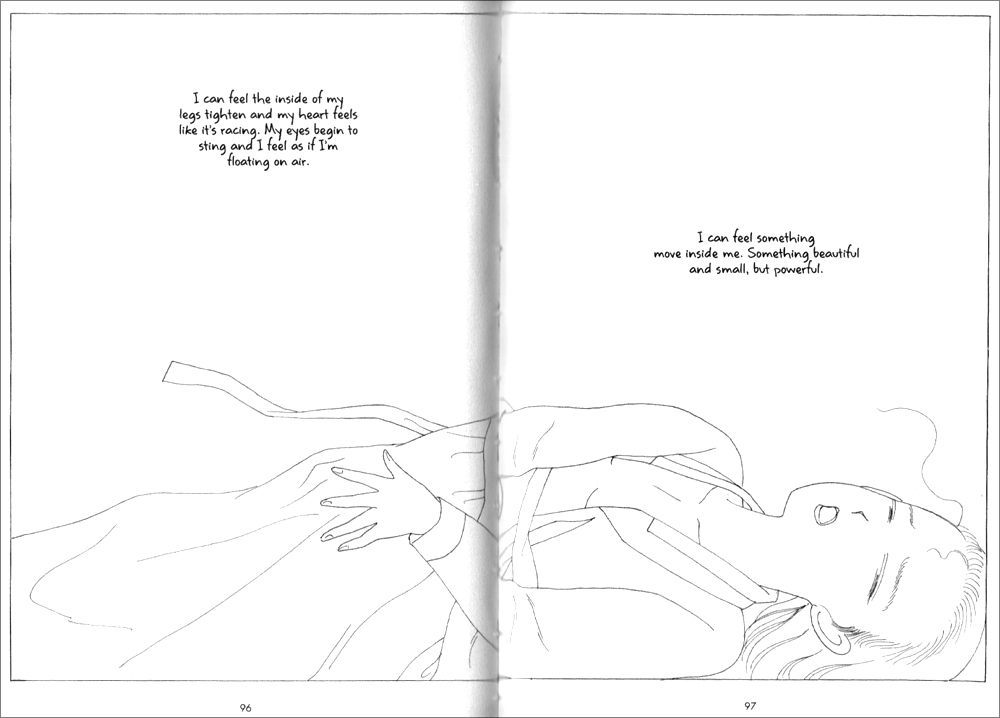

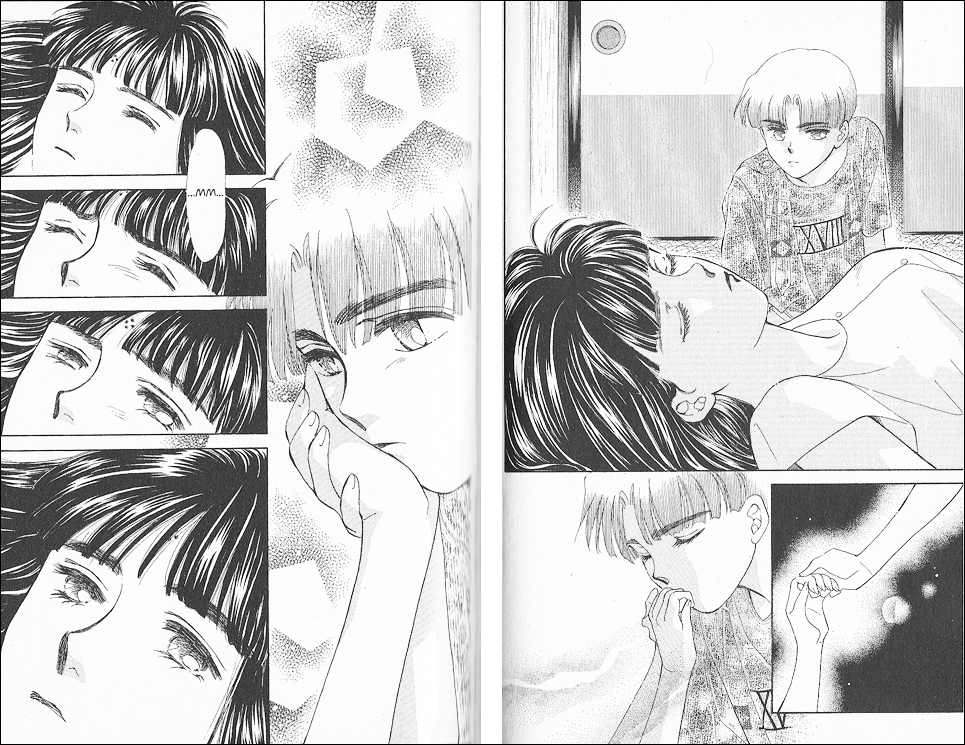

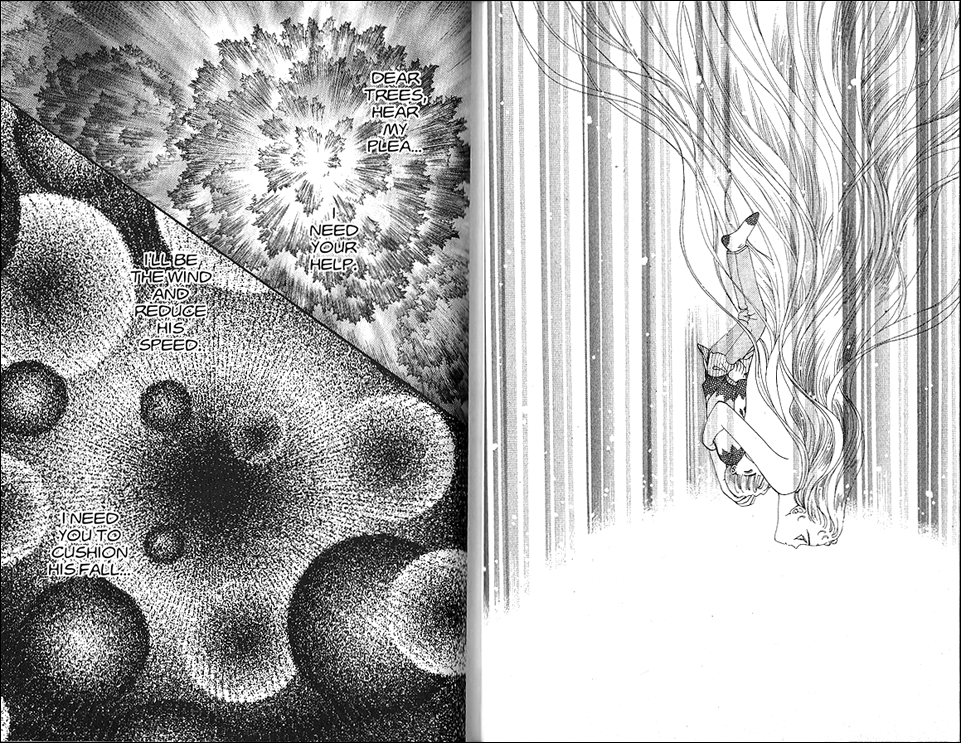

MELINDA: The story’s environmentalist message is nothing revolutionary either, but it, too, is presented with special poignance. With the Kiches’ greatest gift being the ability to speak to plants, it’s the plants themselves that deliver the message, humbly offering themselves up to their fate at the hands of those who would kill them for food or aesthetics, while the Kiches weep.

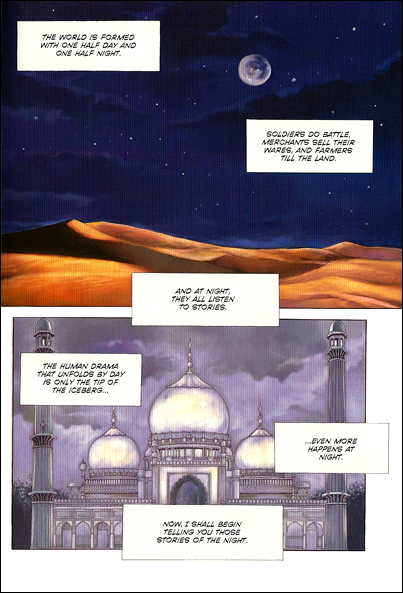

(click image to enlarge)

MICHELLE: I found it sort of inexplicably sweet that vegetables actually yearn to be eaten, because then they become nourishment for a body and, in that way, live on.

You know, while one of the major themes of the series is the quest for identity, it’s pretty impressive that Hiwatari has managed to weave in ideas related to religion, war, and the environment while at the same time crafting a suspenseful story with characters that readers care about. It’s too bad that she doesn’t seem to have been able to replicate this feat again. The only other title available from her in English is Tower of the Future (an eleven-volume series published in its entirety by CMX), which I haven’t read, but that’s because its premise doesn’t thrill me. Maybe she just gave all she had to creating this series, and was never able to duplicate its special blend of awesome.

MELINDA: Honestly, even if Please Save My Earth was the only work she ever created, I think she’d be doing pretty well for herself. The series moved readers so much when it was originally released, they had to start including disclaimers in the tankobon volumes reminding people that it was fiction. Apparently Hiwatari received letters from readers who believed they, too, were having the moon dreams and that they’d been reincarnated from members of the society Hiwatari created. You will spot the disclaimers in the English versions as well.

Though it would be easy to write off those readers as just a few crazies, honestly I can relate to their delusion on some level. This is not to say that I’ve confused the series with reality, but because Hiwatari so skillfully grounds her fantastic story in real emotional truth, it’s remarkably easy to believe if one has enough desire to do so. And since the series comes so close to fulfilling my own personal fantasies (at least those from a particular age), I can easily imagine myself as a teen, so desperately wishing for the fantasy to be real, it would take northing more than that basic core of truth to convince me completely, though I most likely would have kept those thoughts to myself. Fiction can be so powerful when it’s done well.

MICHELLE: I’m not sure if I would’ve believed in the fantasy, even as a teen. After a certain age, I was overly impressed by my own cynicism. :)

I do have to wonder whether PSME‘s sequel, Boku o Tsutsumu Tsuki no Hikari (which translates to “The Moonlight That Surrounds Me”), engenders such passionate fans. I found its first volume to be seriously lacking and have tried very hard to forget the image of Shion and Mokuren as sort of… spectral babysitters for the children of the original cast.

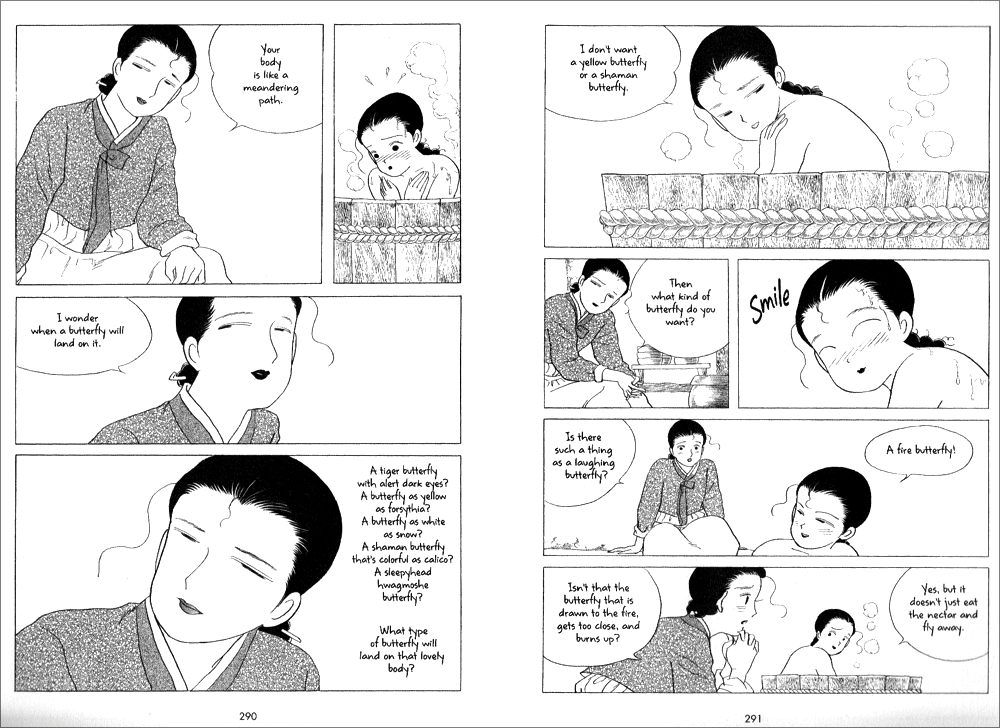

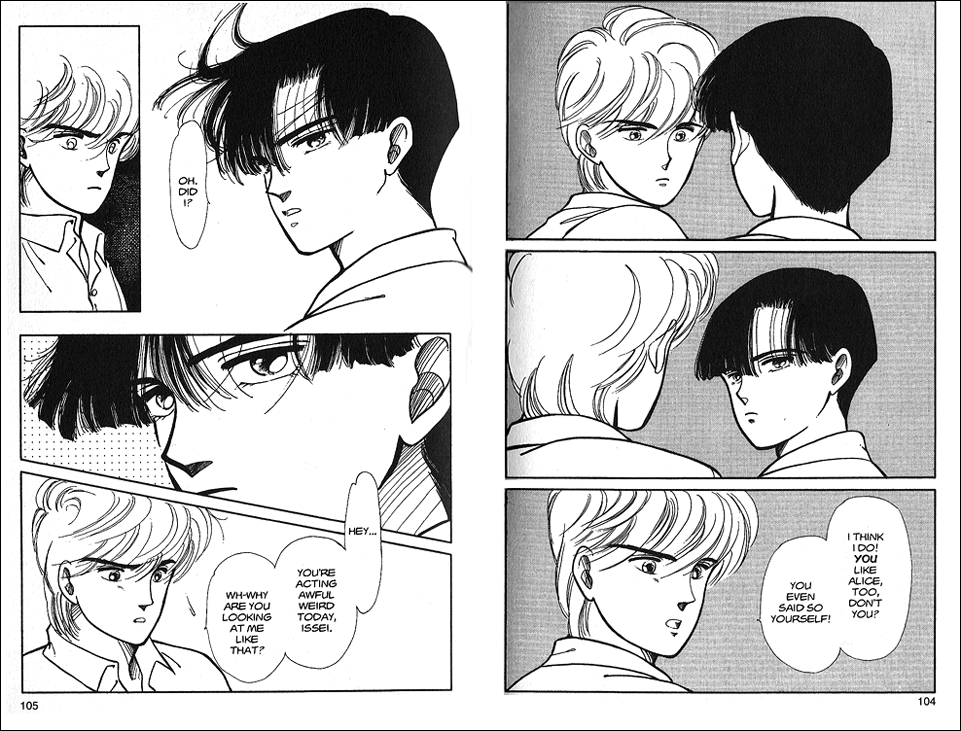

The art style has also changed, and not for the better. It’s a shame, because Hiwatari was able to create many beautiful pages—say what you will about the possible squick factor of an eight-year-old boy kissing a teenage girl, but that sequence between Rin and Alice in volume twenty is seriously lovely—and often evoked a kind of Moto Hagio, Keiko Takemiya feeling with her spacescapes.

(click image to enlarge)

MELINDA: I’d say she was definitely influenced by the 49ers, and there are elements of the story, too, that remind me of Takemiya’s To Terra…, particularly Mokuren’s deep longing for Earth. Hiwatari’s story is more relationship-driven (it is shoujo, after all) and more optimistic about humanity by far, but I can see some influence there. Her artwork, for me, represents the best of both worlds. She has the depth and grace I associate with older shoujo, but with a more modern touch. I’m sorry to hear that her style has changed.

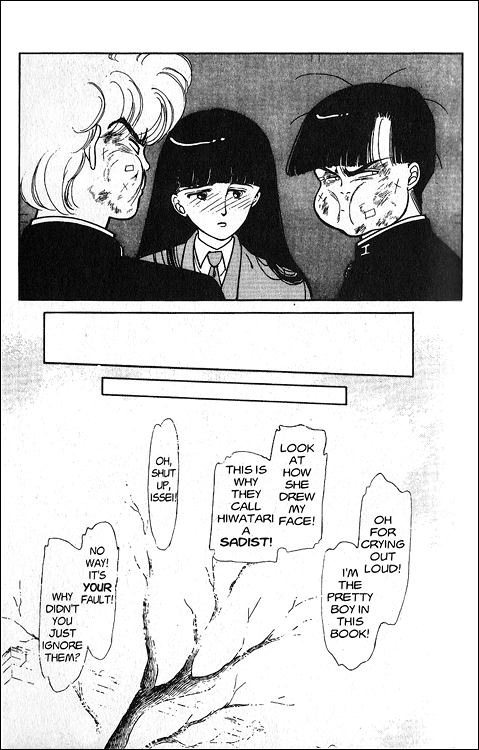

MICHELLE: Although the tone of the series grows more serious as it progresses, she also manages to employ her artwork to humorous effect, seemingly deriving great glee from depicting Jinpachi and Issei in deformed ways after Shion contracts a biker gang to beat them up.

My favorite moment, though, is when Jinpachi’s stunned reaction to the news that Alice is engaged to Rin spans two pages and Hajime quips, “There could be no greater testament to your affections than that you expressed your shock with a double-page spread.”

MELINDA: I loved that comment too! Hiwatari breaks the fourth wall quite often, especially in the early volumes, and to genuinely humorous effect most of the time, which is pretty rare for that kind of gimmick in my personal experience. Rereading the first volume, my immediate reaction was that I’d forgotten how funny it was. I particularly enjoyed scenes depicting an exasperated Alice lying in bed, repeatedly reminding herself not to resent her father for the promotion that brought them to Tokyo (and also that Rin is a turd).

Also, I really have to bring up Rin’s rhythmic gymnastics again, because the visuals made me giggle EVERY TIME. I was sad to observe that Shion had no interest in the sport.

MICHELLE: Oh yes, that same posture and grumbling from Alice occurs two or three times, I think! And, actually, Hiwatari doesn’t utterly abandon humor, it just becomes more surprising when it does show up, since it’s usually capturing Shion in a rare goofy moment.

I think her artwork sort of… cleans up a little around volume four, too. The first three felt a little cluttered, and though the floral motif continues throughout the series, it felt like we began to get more space to breathe after a while, with panels growing larger.

MELINDA: I completely agree. In later volumes, Hiwatari finds ways to use the floral images most effectively. For instance, in that Rin-Alice kiss scene we both like so much, the way the leaves wrap themselves around Rin’s head as he moves in for the kiss is actually sort of haunting to my mind, as though he’s receiving the same essential nourishment from Alice’s kiss as the plants did from Mokuren’s song.

I feel like we’re winding down here, but before we wrap up, I’d like to talk a little about the series’ female characters. Despite the sci-fi setting, in some ways the series is typical shoujo romance, with its many romantic entanglements at the core of the story. On one hand, given everything else that’s going on, I think this illustrates pretty well the fact that all human existence pretty much revolves around sex and romance, as little as most people want to acknowledge it. Put a small group of adult scientists (from anywhere) alone on the Moon, and see if their daily lives don’t eventually come down to who’s getting it on with whom! I think Hiwatari really hits the nail on the head with all the petty jealousy and infighting, most of it over sex, one way or another.

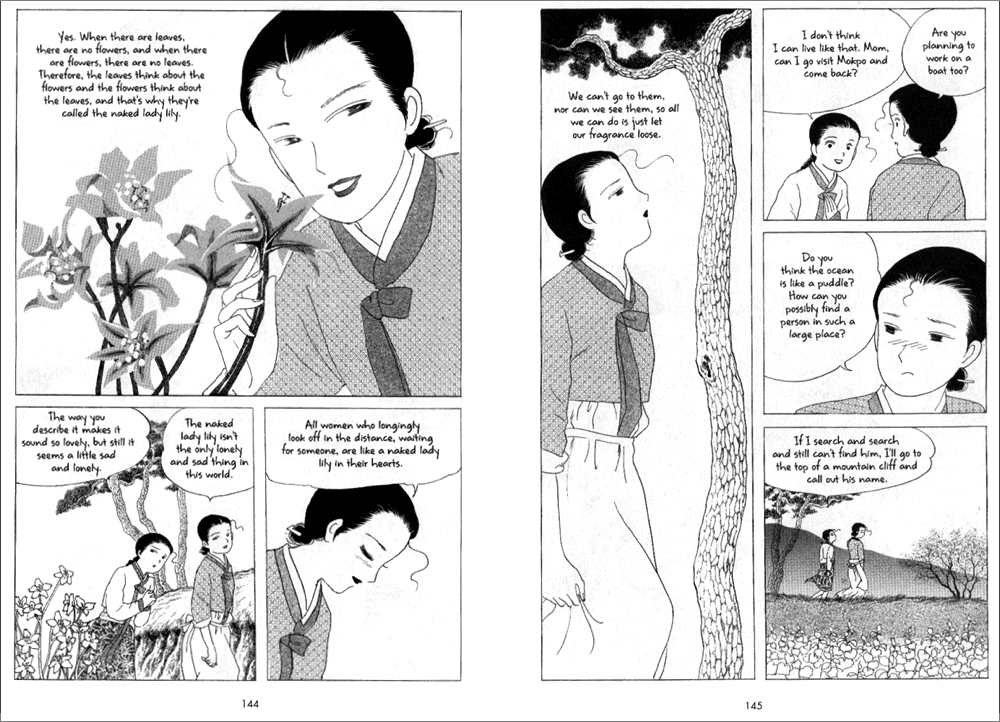

But getting back to the women… though I’ve already gone on a bit about my turnaround over Alice, whom I originally (erroneously) lumped in with a thousand other personality-impaired shoujo heroines, what about the others? Sakura/Shusuran is particularly interesting to me. Though she doesn’t receive the same authorial focus as Alice, or even Issei’s former self, Enju, she’s the only one of the core female characters who isn’t at all obsessed with romance. What’s her deal, do you think? Events in Sakura’s life would suggest that Shusuran might have carried a secret torch for Enju, but that’s not necessarily so, and I hate to define someone like her by her relationships, because that really doesn’t seem to be her priority at all. Thoughts?

MICHELLE: We really do not learn very much about Shusuran’s background, but there are a few telling moments that might explain her perspective on romance. There’s a brief scene in volume six where she receives a wedding announcement confirming that the man she once loved has found someone else. “I had a feeling this was coming, but shouldn’t I react somehow? My heart’s been broken and I’m not even crying.” Later, when she’s watching an Earth TV program with Enju and Mokuren, she argues vociferously that, having married a man she loved, the heroine should not now ditch him when another fellow comes along, no matter how perfect he might be. This leads me to wonder whether the plot of that show resonates with her a bit.

In the end, she decides to support Enju in the latter’s whole-hearted pursuit of love. Do I think she has a thing for Enju? Not really. I just think she’s probably a bit jaded, yet wistful, and the fact that Hiwatari uses her as a kind of authorial mouthpiece also has probably got a lot to do with her pragmatic approach.

MELINDA: I do love the brief scene where Issei comments that Sakura has the wrong hair (Enju’s hair), and Sakura rebuts that Enju’s hair was always the best. Despite her password (“I’m sick of babysitting Enju”), she is always on Enju’s side, and I really enjoy their friendship, in both the past and present lives.

Though the series does focus on romantic relationships in terms of moving its plot forward, I think it’s significant that the most honest relationships we see in the series are friendships between women. Shusuran and Enju, Mokuren and Mode—when it comes to really counting on someone, the women take care of each other better than anyone else can. Though it’s interesting to note that in their present lives, both Enju and Mode (if our theory is right) have been reborn as male. I wonder if it’s a reflection on our society that Hiwatari declined to give Sakura and Alice other women they could really count on as they had in the past.

MICHELLE: That’s an interesting observation about the two women who were reincarnated as male. I’m not sure whether Hiwatari planned it as a critique or not, but it sounds at least possible. This reminds me of how frustrating it was to watch certain pairings completely fail to communicate with each other properly. The chief culprits here are Shion and Mokuren, who each persist in believing that the other never loved them. It’s a relief when Alice finally lays out Mokuren’s feelings clearly, but Rin never reciprocates.

Do you think Shion loved Mokuren? If so, why didn’t her kiche (the forehead marking that designates Kiches Sarjalians) disappear? My theory is that because that specific act was motivated out of revenge mingled with a desperate desire for a human connection with anyone, the kiche stayed in place. But after Mokuren forgave him and created that familial bond with him, he did genuinely come to love her, but regarded her as so precious by that time that he didn’t want to inflict his damaged self upon her.

MELINDA: I do think Shion loved Mokuren. I was pretty moved by his breakdown in volume nineteen, which seemed like the first real glimpse of sincerity he’d ever shown anyone. Something I really appreciate about the series’ reincarnation theme is that I’m able to acknowledge Shion’s feelings for Mokuren without feeling any pressure to excuse him for his violation of her. I don’t have to root for their relationship, because they aren’t actually the story’s protagonists. Alice and Rin are. It’s a sneaky way around the whole rape-as-a-precursor-to-love thing, and I kind of love Hiwatari for figuring it out.

I know that the story is vague about Mokuren’s kiche, but my own interpretation has been that her kiche didn’t disappear because she was born from so much real love between two Kiches (who are forbidden from marrying or having sex) that there was nothing that could take away her gift. She is a true Kiches Sarjalian in a way that has perhaps been forgotten by her people. I’m not sure the text really supports me on this, but that’s my theory. :)

MICHELLE: The text is spectacularly unhelpful in this regard! And, of course, the fact that it didn’t disappear made Shion believe it was Mokuren who didn’t accept him, thus perpetuating the whole angsty cycle.

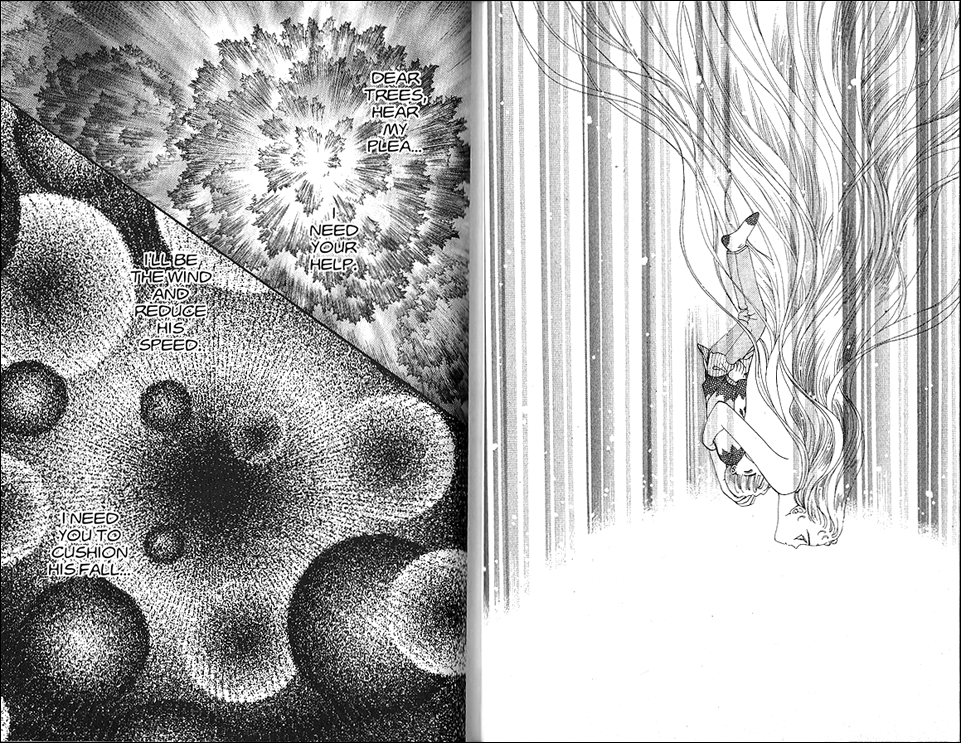

MELINDA: Okay, so here we’ve talked for days, yet I feel that we’ve practically ignored one of the best features of this series: AMAZING FEATS OF ESP.

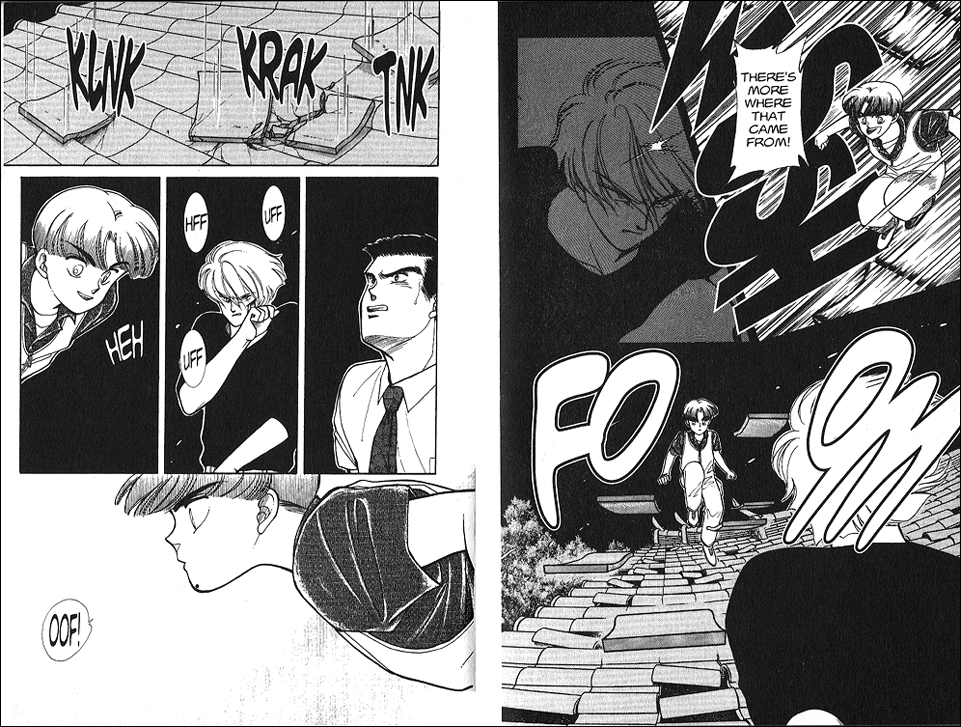

MICHELLE: Ha! My feelings about the “ESP” as seen in this series are pretty mixed, actually. For one, um, no one is really experiencing any extra-sensory perception or, like, predicting the future. Mostly, they seem to have something akin to telekinesis, and can also fly and teleport and things like that. Yet, terms like ESP and “psychic” are bandied about without reservation. The only semblance of what I’d consider the common definition of a psychic is the fact that Shion and Mokuren both dream of their future lives.

And yet, I felt that Hiwatari handled the explanations of their abilities in a pretty graceful way, by having Mr. Tamura (a friend and protector to Haruhiko, who gets involved when his boss’s son is harassed by Shion) learn all he can about it. Too, that battle at the temple between Rin and Mikuro (Tamura’s “psychic” buddy who mostly helps Haruhiko but is also concerned about Rin) is pretty freakin’ awesome.

(click image to enlarge)

MELINDA: Okay, okay, so yes, they say “ESP” when they mean “Psi,” which encompasses all of that, though I’d say that the so-called “Synergetic Cascade,” a type of telepathy that the Sarches (people with psychic powers, which includes most of the scientists on the base) use to trigger thoughts in other people’s minds, falls clearly under the “ESP” umbrella.

I can’t lie. I absolutely love every instance of ESP, Psi, TOTAL AWESOMENESS (or, you know, whatever you want to call it) that occurs in this series. I am such a sucker for stories in which this is well done, and I think Hiwatari does it very well. Seriously, it’s just a thing for me. My mother raised me on Zenna Henderson, and the effects remain to this day.

Also, I am in total agreement over the kick-ass qualities of Rin’s battle with Mikuro. Who says shoujo manga doesn’t have great action sequences?

MICHELLE: When you say shoujo with great action sequences, my mind automatically goes to Akimi Yoshida’s Banana Fish. And then my mind proceeds to a what-if place… what if Yoshida and Hiwatari had collaborated on a story when both were at the height of their skills? I think it would possibly have been the greatest shoujo manga EVER.

I also think it’s really cool when Jinpachi finally gains some control over his abilities in the final volume and gets in some teleportation action. In that way maybe he even surpasses Gyokuran.

MELINDA: Oh, there really are not words for how much I want to read that imaginary collaboration!

And yes, exactly, Jinpachi does surpass Gyokuran! They all surpass their past selves in some way or another. Even Haruhiko, who displays the least growth over the course of the series, is able to work past Shukaido’s pride and be more honest than Shukaido ever was. And here we are, back at the series’ primary theme: rebirth. As I say that, I realize how ludicrous it was for me to ever be seeking an anti-religion message in a story about reincarnation. Yet Hiwatari gives us so much to chew on, it’s actually possible to contemplate that possibility.

MICHELLE: I don’t think it’s ludicrous at all. This is definitely a series that opens itself up to myriad interpretations. I suspect that might be the very reason why we’re here today talking about it!

MELINDA: It might very well be!

For more discussion with Melinda & Michelle, check out their regular features, Off the Shelf and Let’s Get Visual.