Editor’s Note: This is part of an ongoing roundtable on Orientalism, more or less focused on Habibi.

_____________________

Throughout high school, Craig Thompson’s Blankets was the only comic book in my collection that people repeatedly asked to see and borrow. It’s telling that I didn’t technically own it, having borrowed it from another friend. I felt a little jealous on the part of the other comics I owned—Blankets was fantastic, but it became the only comic people asked about. My mom read it, and then our neighbors read it. People wanted to tell me that they had heard about this sophisticated ‘graphic novel.’ I chalked it up to a few things: its technical skill justified it as being art (wrongly), its length meant it was serious, and by this point, the name rang a bell. My friends and parents and parent’s friends were used to hearing me talk about comics as a serious form of expression, and now they heard Time or NPR bring up Blankets. I got sent newspaper clippings about it from relatives. People were curious, willing to spend time with the book, to be in the know about something critics declared both revolutionary and emotionally relevant. I was grateful, but again, a little jealous for all the other comics I was reading.

With Habibi on the horizon, I’d set my hopes on Craig Thompson championing virtuosity as a sophisticated and subtle storytelling vehicle, providing a powerful devil’s advocate to the linguistic or minimalist approaches to comics making that seemed, oftentimes, more effective. But I was anxious about the Orientalism foreshadowed by Thompson’s comments, or the remarks of better-informed friends.

A month ago, opening Habibi on the long bus ride back from SPX, I was more than baffled. It was, after all, an Orientalist book. But Habibi—even for a decades-spanning romantic epic—followed a shocking amount of familiar tropes from American melodrama. In fact, it perfectly enunciated not one but two different ‘cluster’ definitions of melodrama. (I had studied narrative at Carleton College, which, yep, I just graduated from.) Two foundational theorists, film scholars Linda Williams and Ben Singer, admit the impossibility of finding a melodramatic work that embodies every commonality they high-light, but Habibi comes pretty damn close.

Saying ‘melodrama’ on a crowded blog might be irresponsible—colloquially, the word is strictly pejorative, and engenders the bad taste of the Lichtenstein blondes that high-brow critics have reduced comics to for years (and while savvy critics now make exceptions, still do.) I’d rather approach Habibi through the lens of film and narrative study, where melodrama is less a genre than an evolving narrative structure or mode, and can be found across most genres and media—particularly in America. The essence of melodramatic storytelling lies in desperate situations of impossibly heightened stakes. When the risk appears ridiculous to its audience, and unworthy of the tears, grandiosity and suffering, melodrama loses its poignancy and becomes kitsch.

This approach comes from scholar Linda Williams, whose book Playing the Race Card and a few killer essays, trace the legacy of melodrama in America’s cultural and racial history — a history which Habibi is indisputably, if unconsciously, a part of. On the other hand, it’s also worthwhile to study melodrama as it’s commonly understood, as a historical mode that exploded and matured in American culture, petered out in the middle of the twentieth century, and stemmed from nineteenth century sentimentalism. Craig Thompson seems to have gone for this explicitly, judging by his mention of ‘Cowboys and Indians.’ This theory is forwarded by Ben Singer in his book Melodrama and Modernity.

I could draft a thesis on melodrama in Habibi, and have a ball bringing in related theories, especially those of Laura Mulvey and Clement Greenberg’s work on kitsch. That’s not what I’m prepared to post here. A survey of William’s and Singer’s points illuminate just how exemplary of a melodrama Habibi is, even where Thompson does subvert the mode in remarkable ways. However, this ‘melodramatism’ problematizes Habibi as an Orientalist and American “text,” and as a book that is slated to receive a fair amount of outside-comics attention.

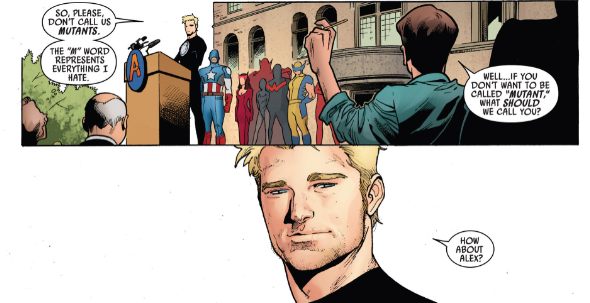

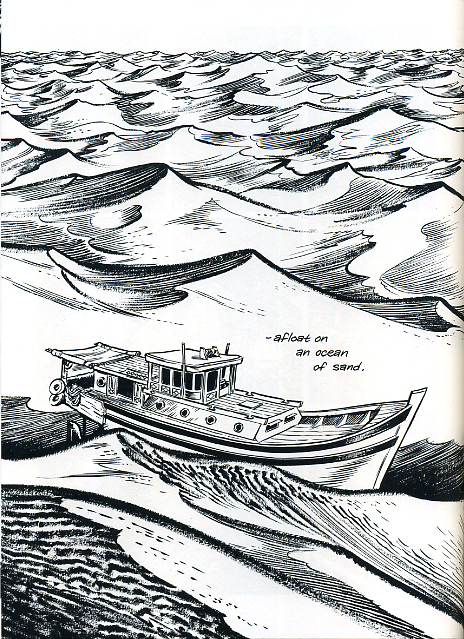

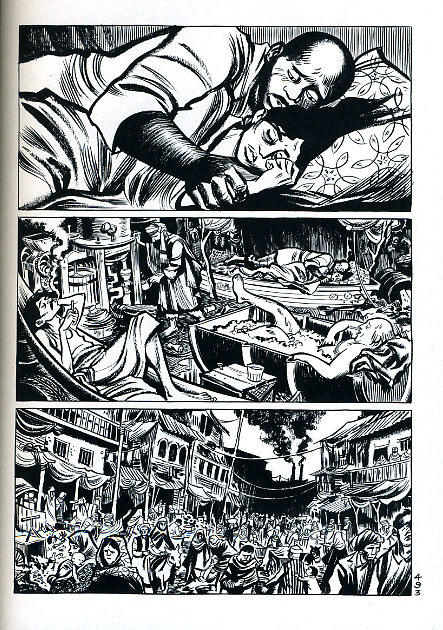

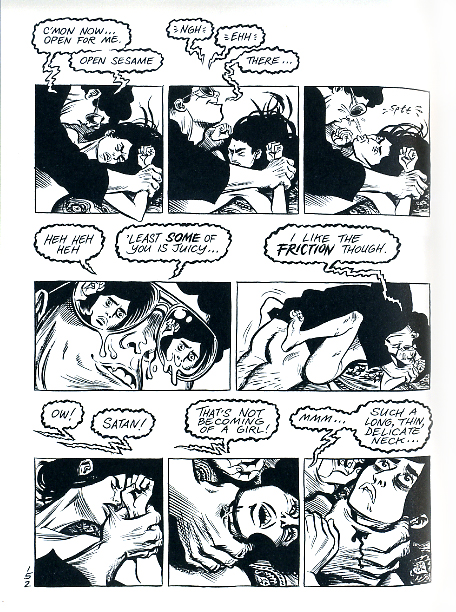

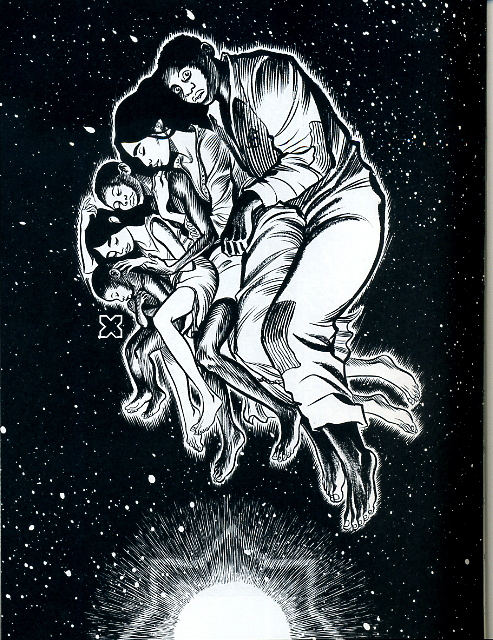

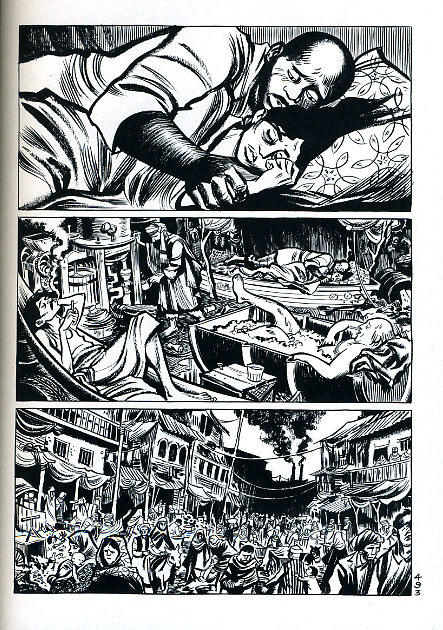

Visual Excess and Violence, Realism and the Tableau

Formally, melodramas are marked by visual excess, manifesting in traits like overwrought expressions and gestures, thrilling chase scenes, ’swelling busts,’ musculature and gratuitous violence. Williams especially notes that this excess is accompanied by an obsession with realism—not realistic storytelling or behavior, but realistic effects that enhance the sensational thrill of the action. Reading Habibi’s virtousity as a kind of visual excess could confirm some of my worst fears about ‘pretty’ comics, which merits another post altogether. Thompson stirringly choreographs chase scenes, daring rescues, and death-bed hand wringing in the tradition of classic D. W. Griffith melodrama (a comparison already made by Corey Creekmur on this blog.) Habibi is also a remarkably violent work, particularly with Dodola, who we watch repeatedly raped and abused. The sensational visual of Dodola’s naked body also appears across the countless astral, psychedelic tableaus of Zam’s fantasies.

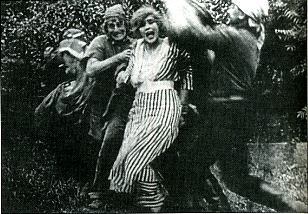

Still from the Perils of Pauline, 1914

The tableau, a melodramatic tendency to ‘freeze’ the action in an appealing and emotionally charged still, is featured prominently in Habibi. The narrative eventually breaks down into a slew of tableaus by the end.

To Habibi’s credit, Thompson does confront this visuality (and the male gaze) in Zam’s horror of it. Near the end, Dodola’s intuits that “a man’s inspiration is visual, but for a woman, it’s the narrative” (639). Habibi is both supervisual at its end (with the tableaus) and anti-visual, especially in the blank nine-by-nine grid of Orphan’s Prayer, where Zam confronts the blasphemy of visuality and image-making. Here his struggle with himself is echoed in Thompson’s, as creator. Zam forgives himself, and the image-making is again permitted, and for better or for worse, Dodola is returned to a visualized object of desire.

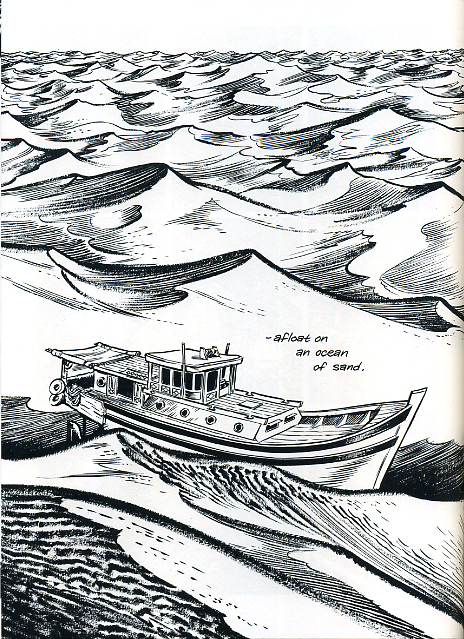

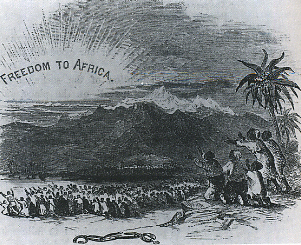

Insistence on Virtue, Rural Goodness and Exotic/Industrial Evil

Most, but not all melodramas insists on the virtue of the characters, who in the beginning are tainted by a ‘fall’ from grace and are forced to leave an earthly manifestation of paradise (often depicted as a rural home.) The plot then revolves around their eventual return to ‘home’—either by ascending to heaven through death, or withdrawing from society back to the countryside. The peak of melodrama’s popularity coincided with the rise of industrialism, and melodrama’s nostalgizing of rural living appealed to a increasingly urban population.

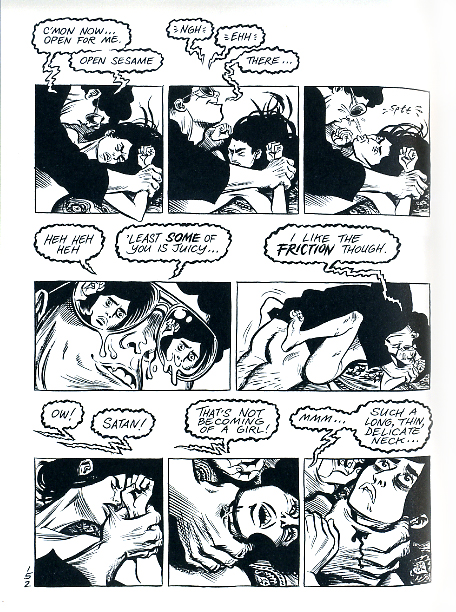

reprinted in Ben Singer Melodrama and Modernity

Melodrama must simultaneously taint and preserve its protagonists’ virtue. This is commonly achieved through victimization, physical suffering, and occasionally self-mortification, often expressed as graphically as possible, but without showing actual genitalia. The protagonists’ virtue is further established by reducing the cast, good and bad guys alike, to morally dualistic psychic types, good and evil. ‘Corrupt society’ is often depicted as ‘anti-nature,’ a dirty and over-stimulating center of hedonism and crime, or an exotic location where brutality and taboo-breaking provide a implicit foil to the American rural homestead. The precedents for Dodola and Zam’s rural boat-house, the palace and urban Wanatolia, and even Habibi’s environmental metaphors of water and damming, can be found in Way Down East, the film Giant, and countless other pulps and melodramas– which also predict the ending where Dodola and Zam, orphan in hand, withdraw back to the desert.

Finally, melodrama’s classic emphasis on purity and taint is made explicitly in Habibi’s text and visuals. Dodola is told that the stain of her broken hymen “proves that she was pure” in the first few pages of the book (14). In Zam’s fever dreams during his lengthy, self-mutilating surgery, Zam calls to Dodola, “I’m pure again! Will you take me back?” Dodola replies, “The question is… am I pure enough for you…?” (p. 337). Its worth repeating that this doesn’t make Habibi bad per se; and I think Dodola’s ’de-flowering’ by her first husband is both human and highly nuanced. Similarly, the most powerful subversion Thompson provides is how he makes the issue of ‘purity’ and ‘taint’ irrelevant after The Orphan’s Prayer, even while most of Habibi’s melodramatic facets are restored or accentuated. Dodola goes full-on into sentimental mother mode, (having experienced a significant Scarlet O’Hara + Way Down East child-loss episode before,) and they return to the desert, “God’s Domain” (630).

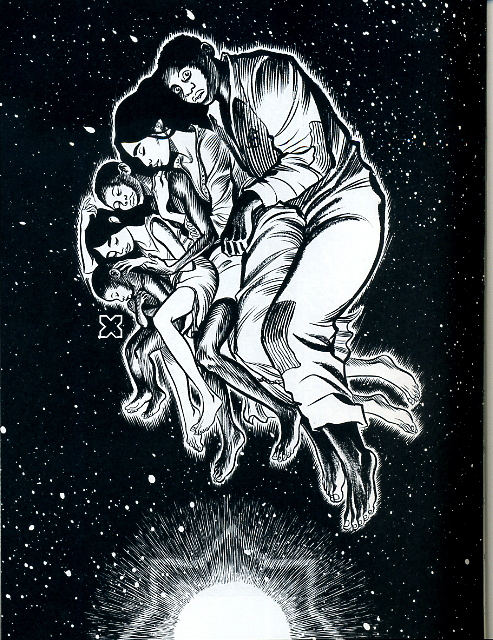

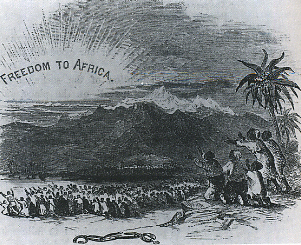

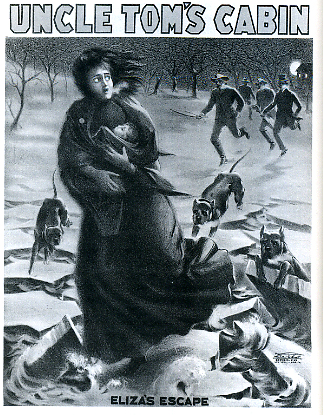

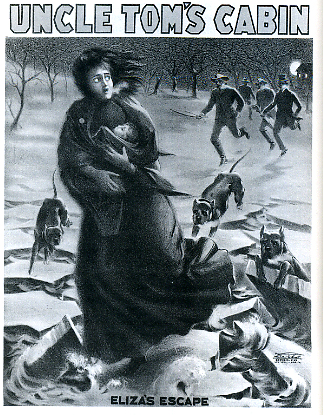

from the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, reprinted in Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card

Non-Causal, Circular and Non-Traditional Storytelling—“Just in Time”

The ‘magical’ expunging of character’s taint through suffering highlights the most subtle, but perhaps most fundamental commonality of melodrama. Narratives are often called conservative, in that they don’t address the character’s conflict with society, (If X is so innocent, why is she suffering?) Melodramas often can’t arrive at logical conclusions—people either kiss and make up, or withdraw from society altogether, without the conflict ever being ‘solved.’ Melodramas compensate by making sense emotionally, where the audience vicariously experiences the progression of joy to suffering to despair to joy. The return to the rural home-space doubly asserts this circular structure. The extended periods of unremitting suffering and pathos often “burst” in scenes of recognition, (finally!) and rescue, (just in the nick of time!) and occasionally even more pathos (too late!) In either case, the moment of just-in-time/too-late signals the expelling of taint, where the characters are ready to return to paradise. Habibi’s plot is fueled with pathos, from the caravan rapes to palace intrigue, to Zam’s despair and near suicide at the cliff-hanger of Orphan’s Prayer. I’d like to repeat that for all its melodramatic trappings, HabibiTRULY subverts the use of suffering as a purifier, and makes noise in declaring its self-destructive futility. Yet Habibi’s cosmic self-forgiveness, expressed by the tableau of Zam walking home, and its substitution of the concern of purity with child- and motherhood, underlines how Habibirelies on a similar perspective shift as Griffith’s Way Down East and many other melodramas. Habibiending is more believable: no puriticanical foster-parent forgives a fallen woman because she nearly died in a blizzard. Habibi relocates the perspective-shift to the internality of the protagonist, making the victimization an issue of self-victimization. Unfortunately, this doesn’t restore the humanity of the oafish sultan, dwarf adviser or bland eunuch friends.

As a reader, you might say, ‘sure, you just described a lot of points that show ways in which Habibiis melodramatic, and a sophisticated example of one at that. We knew that.’ What is striking is that these are all the major components of two very different examinations of melodrama—and its very rare for one example to possess so many. Habibiis a super-melodrama, a balanced synthesis of the escapist, ‘blood-and-thunder’ serial with the American family epic—and with a good amount of Old South narrative thrown in. Habibiis truly Orientalist in that its not only a fantasy of the Middle East, but an imposition of an American story, involving American concerns of race, sexuality, and industrialization, on a foreign, if imaginary, culture. Thompson has explicitly stated that the project was to bridge Islamic and Christian faith, which he DOES execute with incredible poignancy in the stories of Genesis sprinkled throughout. The melodramatic framework that surrounds Dodola and Zam, and constitutes most of the book, works against his best intentions. Its hard not to read Dodola’s escape with baby Zam from the slave market as a direct homage to Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s iconic flight of Eliza with child from slave-catchers. This homage doesn’t prove the universality of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as much as an inability to look outside of American storytelling traditions to what is truly local to the Middle East.

from the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, reprinted in Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card

Habibiis otherwise subversive in several other places: Dodola spends very little time weeping or reflecting on her powerlessness—this soul-searching is left to Zam. But, why is it necessary for Zam to castrate himself, before being reunited sexually with Dodola? Is it just to “heighten the stakes,” to lead the reader to despair of their sexual union, only to reveal a joyous, unexpected solution? Previous melodramas provide troubling parallels with Habibi’s depiction of black male sexuality, which the robustness of Habibii’s melodrama make it hard to ignore.

So what? Habibi for better or worse, seems destined to join Blankets as a ‘Well-Known Graphic Novel,’ the kind your aunt sends you clippings on and seventy-year-old women ask about at baby showers (as happened to me last week.) There’s a chance that they’ll enjoy it—that they’ll be glad to indulge in a rollicking Cowboys and Indians story with enough sophisticated internality, visual reinvention, strong female characters and biracial coupling to qualify a subversion of the mode.

If the reviews in the Guardian and the NY Times are any indication, these aren’t favors the comics community can yet expect from a broader readership. I think the generosity of my reading comes from extensive study of the melodramatic structure—it might be easy to lose what makes Habibi a sophisticated example of Cowboys and Indians in, well, Cowboys and Indians. Let alone the fact that this American story is cloaked in Orientalist trappings, and created and published during our military’s continued involvement in the Middle East. Its hard to ignore that Habibi reflects an American solipsism in our occupation and imposition there, a wishful escape to the world of good-and-evil storytelling, and a refusal to confront really sticky issues of race in a contemporary, or responsible, manner. I’m playing the race card here, but even from my first read through of Habibi, it was hard to ignore. This issue will only be magnified when ‘outside-comics’ readers approach Habibi without any understanding of how innocent Thompson’s intentions were.

Why does lending out Habibi make me feel so much more anxious than lending Blankets did six years ago? Like I said, melodrama is a fascinating and contemporary narrative form, as valid as any other. I recommend melodramas all the time. Yet, how many comic books will a seventy-year-old woman read this year? One, maybe—and if it’s Habibi, I worry that its melodrama, picking up more themes than it can considerately deal with, drifting into kitsch (a term already associated with the comics medium) will represent the entire medium, unfairly, as a space of gratuitous visuality, over-wrought nostalgism, and bad taste.

_________

Kailyn Kent is an artist and one of the folks behind Carleton Graphic Press.