Last November I posted the first of what I hoped would be the first of a series on what might be called comics medievalism here on PPP. This post represents the second of the series.

A number of connections can be made between comics and medieval culture, both through analogy and homology, though it is often difficult to establish whether the parallels we spot between comics and medieval culture are the result of coincidental similarity or a traceable historical relationship. Either way, it is certain that comics are a form of cultural production in which traces of medieval cultural forms (heroic masculinity, arming rituals, millennialism, magic, etc.) survive in the present.

Lately, I have been thinking of the medieval reference at work in Disney’s 1929 Silly Symphony animated short, The Skeleton Dance. The film shows four human skeletons dancing in what is unmistakably an adaptation of the late medieval tradition of the danse macabre. It would be easy to dismiss these Disney skeletons as comic modernization of the medieval tradition with its slapstick physical comedy and goofy music. But this would be to forget the fact that slapstick was an integral part of the medieval danse macabre tradition itself, which used the comic register as a way to level social class difference through the trope of death-the-great-equalizer. Allow me to share a few examples. I mean, who could deny the slapstick dimension of the following woodcut of death and the gentleman from the Der Totentanz series printed by Heinrich Koblochtzler in 1490?

Death’s gleeful pose, along with the gentleman’s comic expression of almost casual surprise, are directly at odds with the grimness of the subject. The style of presentation –death as a campy cabaret act and his victim’s mock expression of surprise– conflicts jarringly but comically with its subject matter.

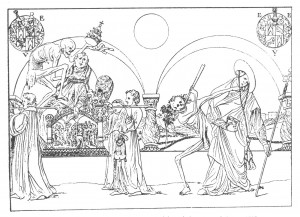

Less slapstick, but still operating on a carnavalesque (or even a Frank Miller-esque) inversion of hierarchies of high and low, sacred and profane, the following print by Nikolaus Manuel dated 1515 shows the pope and cardinal being ambushed and beaten down by dancing dead. The humor resides in the contrast between the dignity of the holy men and the awkward and naked physicality of the attacking skeletons.

Or to cite yet another, more famous, example, Holbein’s 1526 woodcut of the Totentanz shows four skeletons reveling in a danse macabre while a fifth skeleton struggles to escape or return to its shroud. The sloppiness of the skeletons who still bear traces of hair and flesh and viscera reads as both comic and macabre as if to suggest that death is an undignified affair that should be faced with laughter and some disgust rather than piety and reverence.

One thing that all of the late medieval representations of the danse macabre have in common is a sense of address to the viewer, that he or she might be next in the line-dance of the dead. This dimension is definitely present in the Silly Symphonies Skeleton Dance where the dancing skeletons lurch at the viewer in what must have been a frightening sequence for a 1929 audience. In one sequence, the medieval skeleton “eats” the viewer (see the gif below), bringing us into its dance of death and making us part of European history’s unending pile of skeletons.

What I like about this particular moment in the Skeleton Dance is that it demonstrates how drawn animation could create a visual experience for its viewers that no live action film would be able to produce for decades. Moreover, it does so in order to confront its viewer with death in a way that is nearly identical to the address made by danse macabre imagery in 15th and 16th century Europe. The Disney cartoon danse macabre innovates formally in order to produce an effect that harks to a late medieval mode of confronting death.

It’s also tempting to look at the formal parallels that exist between medieval representations of the danse macabre and modern comics. Both share a similar “kinetic” quality and both tend to prefer stretched horizontal band formats as in the following danse macabre mural by Bernt Notke found in the St. Nicholas’s Church in Tallinn. An even more striking parallel with comics resides in the fact that this representation of the danse macabre has captions, a short dialogue attached to each victim in which Death summons him or her to dance while they moan about their impending death. What’s more, this horizontal configuration with captioned dialogue was apparently a fairly common visual format in the late medieval danses macabres. Would it be a stretch to say that these visual representations of the danse macabre are themselves a kind of proto comic book?

In either case, I like the unseemly crossing of the medieval and the modern we see in the 1929 Skeleton Dance and I like even more the campiness with which a subject so serious as death is domesticated without being banished from the imagination in both the medieval and modern examples I’ve discussed. Where does the danse macabre make its way into your comics reading and in what other ways might we think of the danse macabre as a form of proto comic book?