The word of mouth has been abundant and the acclaim unremitting, but what exactly can we learn from the outpouring of reviews of Michael Deforge’s Very Casual—that work of unremitting “genius”, and that artist soon poised to seize the crown now tightly held by the desiccated funksters who emerged during the 80s and 90s.

For the uninitiated, the simplest of descriptions: Very Casual is a collection of stories by DeForge variously published in places like Best American Comics 2011, The Believer, and Study Group Magazine. It won the 2013 Ignatz Award for Outstanding Anthology or Collection as well as the award for Outstanding Artist. His work is easily accessible online as are some of the stories collected in this anthology.

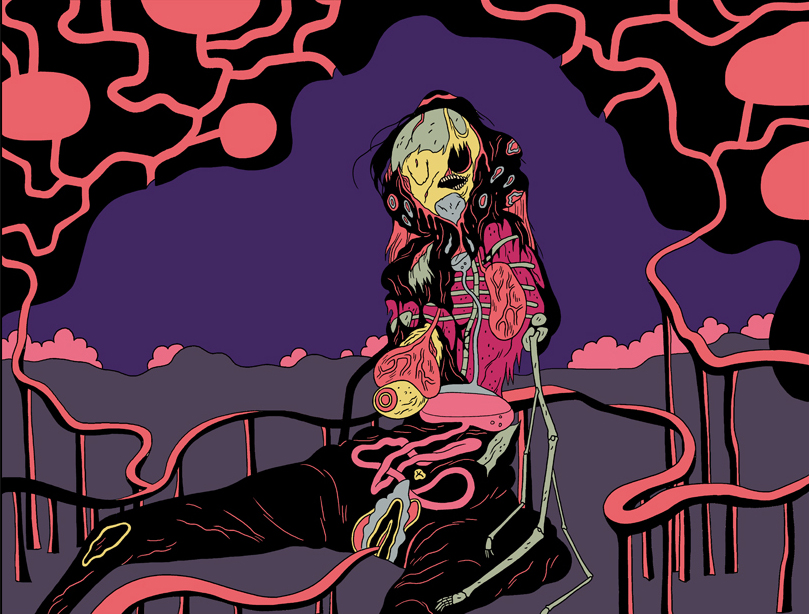

Fans, academics, and journalists have had their way with the likes of Chris Ware and Dan Clowes, thoroughly disinterring the design, complexity, and intelligence of their comics. But what have the esteemed critics of the internet done in DeForge’s service over the last 2 years? Here are some recurring words and concepts from a moderately long trawl: body horror, disgusting, reader beware, favorite, best, winner. The overarching feeling from reading a sizable chunk of Deforge reviews in one sitting is that he is artistically as spotless as a baby’s bottom, a veritable second coming of a cartooning Christ.

Rob Clough writing at TCJ.com in 2011 on DeForge’s early works is certainly entranced by his promise:

“He’s clearly someone who has read everything—superheroes, manga, undergrounds, autobio, etc.—and has a keen sense of comics history. DeForge combines that encyclopedic knowledge of comics with a strong sense of perspective regarding the medium, synthesizing and understanding its strengths and weaknesses. That allows him to comment on and critique not only the length and breadth of comics history, but also to closely examine his own work. Finally, his facility as a draftsman is jaw-dropping. He has a remarkable facility as a style mimic, and the control he has over the page (both in terms of design & line) is incredible for an artist as young as he is.”

Strike that. This isn’t a description of mere “promise”, it is a description of a cartooning God mowing down all obstacles in his way.

On the other hand, it is never entirely clear from Clough’s description why DeForge should be taken for a cartooning deity outside of these statements—is it purely his draftsmanship, his mimicry, and absorption of influence? Or is it perhaps his ability to convince Clough that “body horror” in comics can be a successful endeavor? Clough is also especially drawn to his work ethic and search for style:

“One of the reasons why I like DeForge is, like Shaw, he is an artist who just does the work. Whatever doubts he has about his own abilities or place in the world of comics doesn’t stop him from drawing story after story….I’m enjoying this restless phase of his career as he explores every nook and cranny of comics history, but I’m eager to see how he harnesses his energy.”

I read Clough’s long gloss on DeForge’s comics in 2011 and once again this year. On both occasions, I gleaned nothing in the description of form and content which suggested a mind on the cusp of genius.

Which brings us to the present day and the torrent of praise for Very Casual—the collection destined to put DeForge on the cartooning map. It’s certainly been covered in all the best places.

Douglas Wolk writing in The New York Times only has a fraction of the space allotted to Clough and this allows only for bare description. It seems mostly like a straight recommendation to buy:

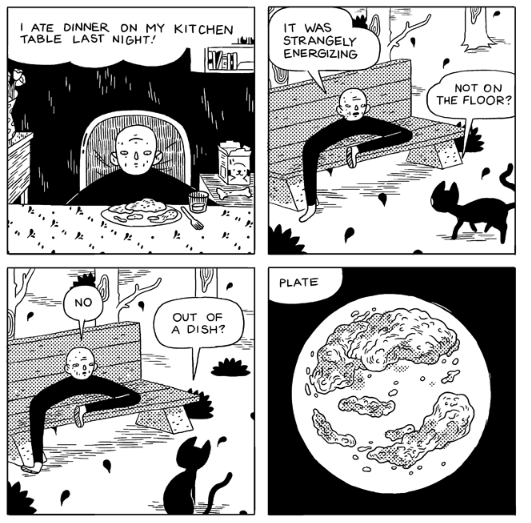

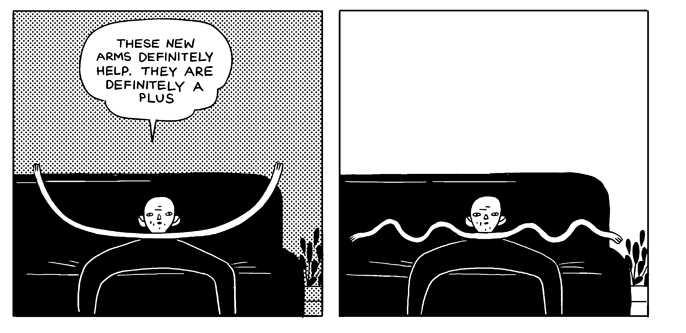

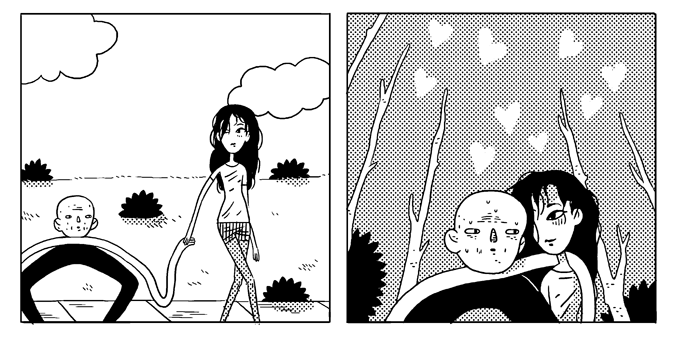

“Everything and everyone in his drawings is dripping, bubbling and developing unsightly growths. He warps and dents the assured, geometrical forms of vintage newspaper strips and new wave-era graphics into oddly adorable horrors; his stories are prone to whiplash formal shifts.”

Sean Rogers at The Globe and Mail gives us description, biography, and recommendation. Once again, we are encouraged to believe that DeForge’s stories are “unsettling”:

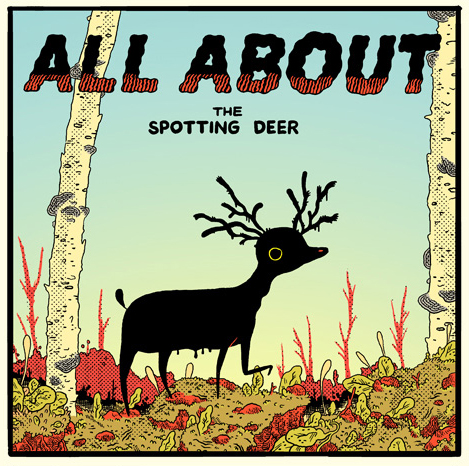

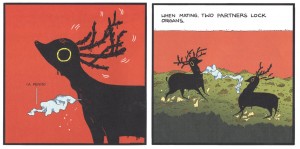

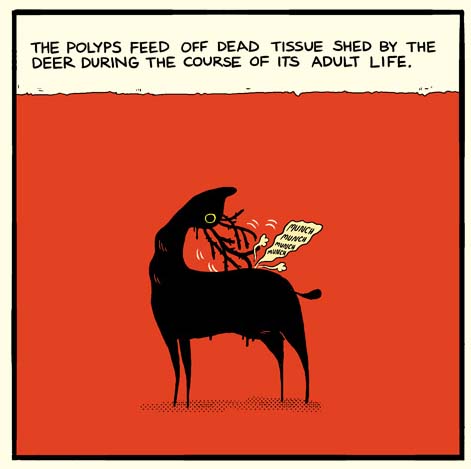

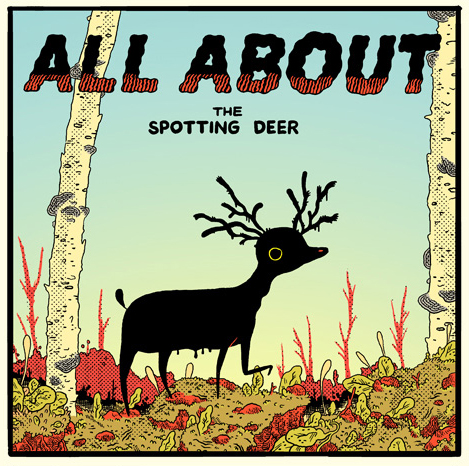

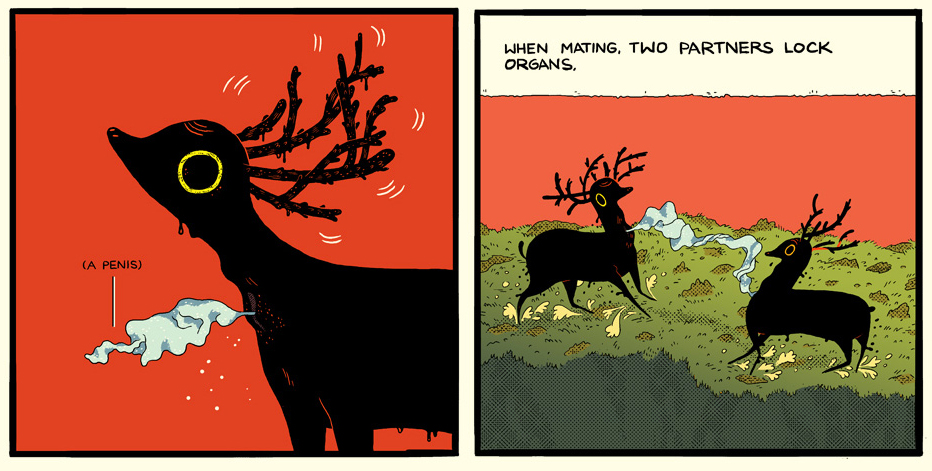

“DeForge’s is a world apart from our own, askew ever so slightly. It’s a world of uneasy cuteness, of pop art degeneracy, and it rewards the curious traveler with remarkable imagery and unsettling stories…Consider All About the Spotting Deer, which lends the volume its striking cover image. A disquisition on a breed of ambulant slugs that only look like antlered fauna, the strip resembles nothing so much as a bizarro Wikipedia page, explaining the social life of these creatures in deadpan, clinical terms.”

Well maybe if you’re a 90 year old spinster who only does crochet in her spare time. The analysis once again offers nothing to bolster the prevailing belief that DeForge is the new messiah of cartooning. It is merely an encouragement to believe.

Brian Heater at Boing Boing is also concerned about his reader’s mental health when it comes to DeForge’s Very Casual:

“Speaking of exercises in public health, here’s a thing that probably shouldn’t be read by anyone — or at least not those prone to nausea and dramatic fainting… Very Casual is always fascinating, mostly grotesque and in the case of the biker gang with cartoon character helmets, actually pretty touch in the end.“

Basically buy because I said so. Really, just buy (if you’re not my grandma).

Timothy Callahan at Comic Book Resources invokes the names of Chris Ware, Dan Clowes, and Charles Burns. He has cited DeForge’s Lose #4 as the best comic of 2012. His reasons? DeForge’s ability to render “Lynchian oddness” and because the issue is “the lightning rod for his talents.”

In a more recent article, he connects the Day-Glo horrors of DeForge to his work on Adventure Time.

“DeForge started working as a designer for the “Adventure Time” animated series beginning with its third season, and that seems exactly appropriate for someone with his sensibility, but in the stories found in “Very Casual” it’s like we’re seeing the twisted underworld of the “Adventure Time” aesthetic.”

But then provides us with more marketing copy in an effort to encourage retail therapy:

“He revels in grotesquerie and absurdity and there’s a deep and profound sadness to much of the work even when the pages burst with a celebration of oddball joy. Disfigurement is not uncommon. And contagion is a leitmotif. DeForge’s comics are gloriously enchanting, but brutal…[…]…DeForge transforms his style and yet maintains a similar sense of tonal unease. These are comics that worm their way into your brain even as you try to process them. In the best way imaginable…There’s nothing, of course, clumsy, leaden, or inelegant in the pages of “Very Casual.” This is a work of supreme skill and unique sensibility.”

Jeet Heer on the other hand can be excused for resorting to the same when presenting DeForge with a 2012 Doug Wright Award:

“Visually, Spotting Deer is a delight, a virtuoso display of stylistic variety. The colours are startlingly unnatural as are the appropriations of different art styles, ranging from newspaper comics to video games to record cover art. It belongs to the line of artists like Richard McGuire and Gary Panter, who possess the ability to seep into your eyeballs and rearrange the wiring in your brain. You see the world differently, with sharper eyes, after reading DeForge’s comics. Like some of the best cartoonists of his generation, he’s bringing to comics some of the visual intensity of painting and forcing us to realize that the visual range of comics is much larger than we thought possible.”

The point of Heer’s statements was description and commendation preceding an award presentation. It is republished here as a stark reminder of how little it differs from all other descriptions of DeForge’s work online. The critic as award giver is certainly a perennial finding in this art form.

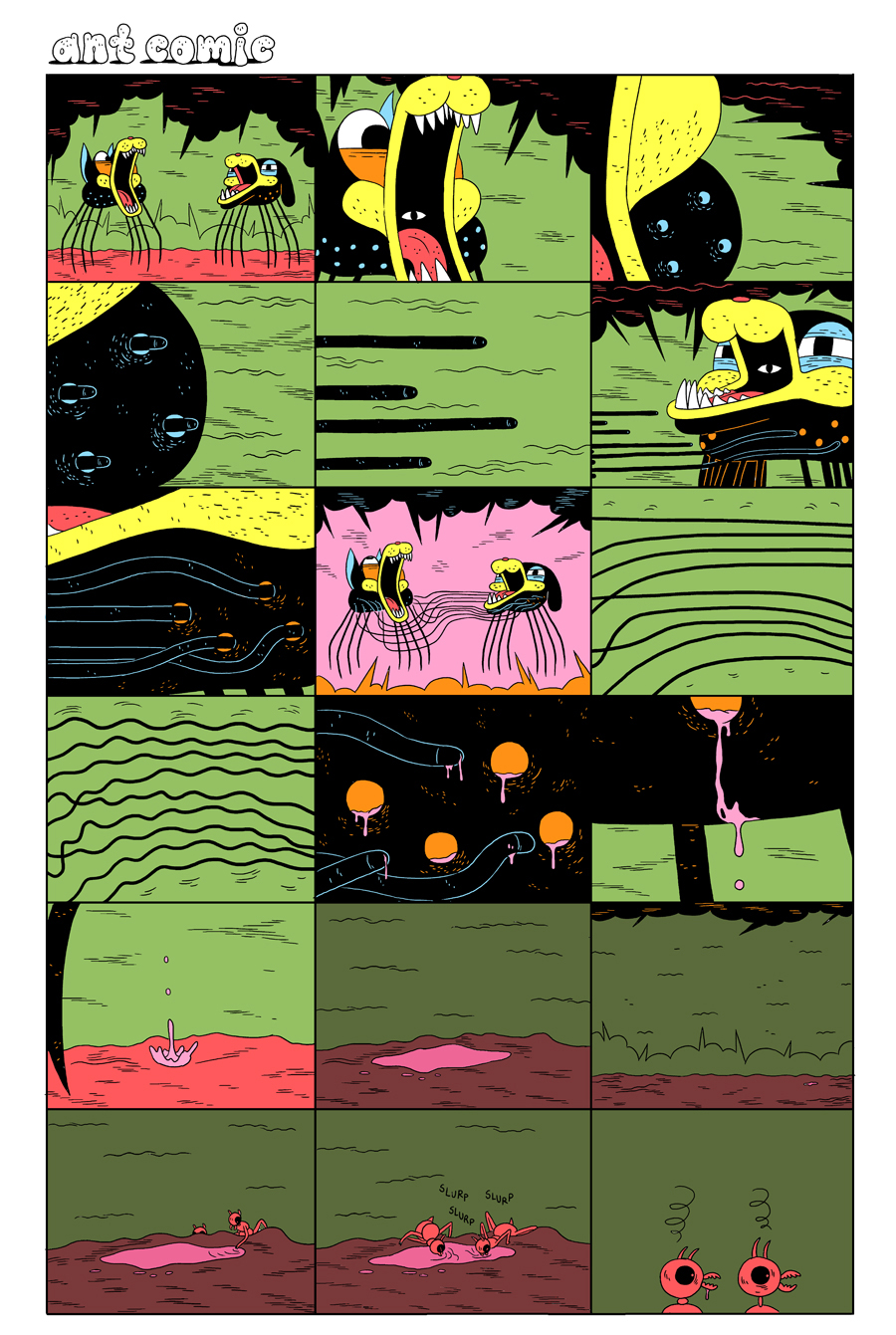

Sean T. Collins has written extensively on Michael DeForge but also confines himself largely to description when it comes to Spotting Deer—the centerpiece of Very Casual. His most extensive examination of DeForge can be found in his review of Ant Comic at TCJ.com. Collins parodies his own predisposition right at the outset with his opening line:

“Oh, look, a Great Comic.”

The more detailed recommendation goes as follows—it is about important things and…

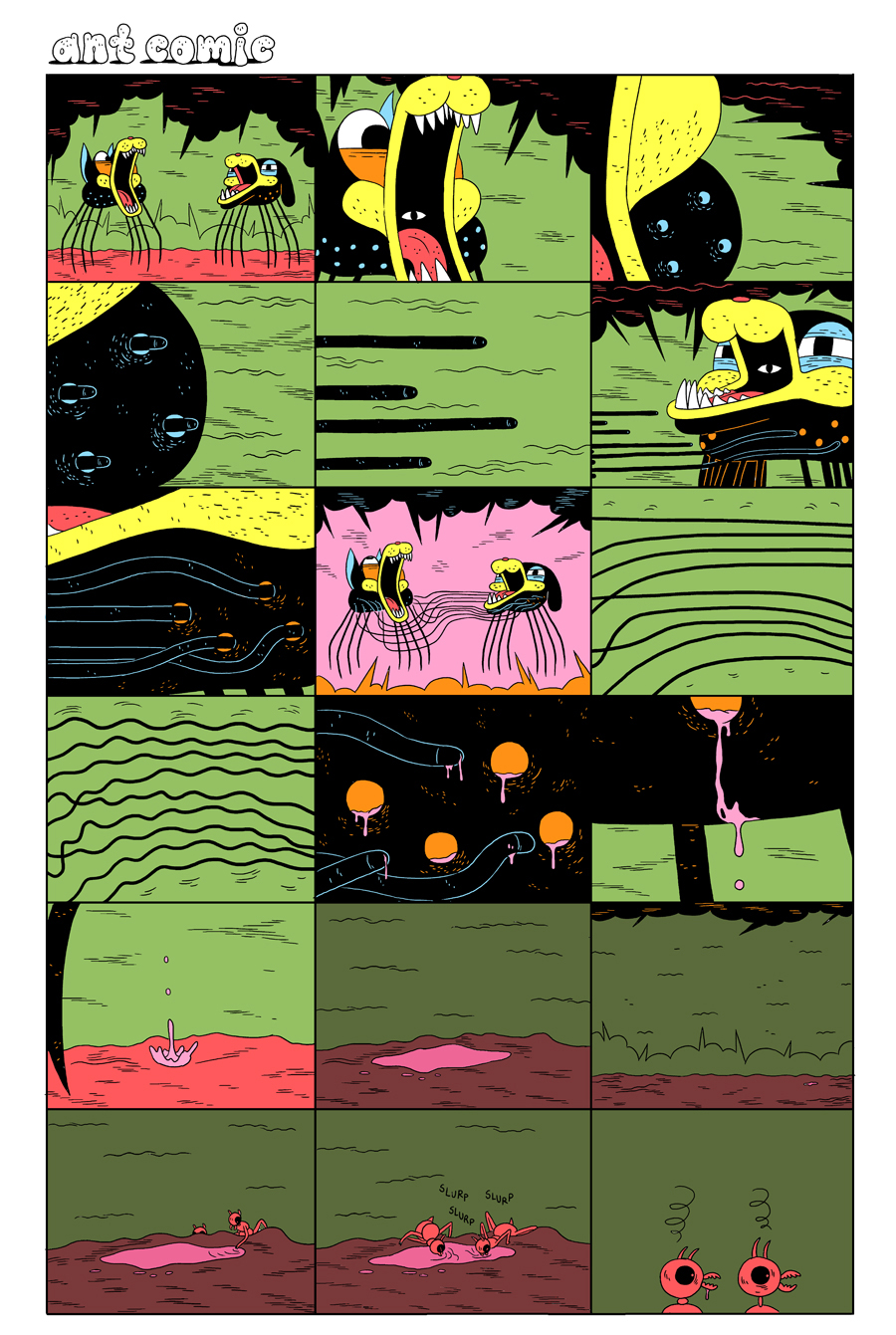

“…the bizarre visual interpretations of the bugs in question are pitch-perfect distanciation techniques, driving home their alien biology by depicting them in ways we’ve never seen, not even close…[…]…The power of these designs fuels the deployment of another one of DeForge’s go-to techniques: juxtaposing grotesque and high-stakes events with blasé, workaday reactions by the characters involved.”

In other words, we should read DeForge because he draws weird insect-humans and has a comedy shtick like the Black Knight with a “flesh wound” in Monty Python and the Holy Grail. It is also:

“…an existential horror story about going through the motions. Life is boiled down to the precious few biological drives ants possess—reproducing, eating, killing threats—which in turn become the social mechanisms that drive the entire colony.”

The question is, why should I read this particular existential horror story and not the hundreds of other existential horror stories lining the warehouses of Amazon.com? And why should I read about these ant-workers as opposed to the ones covered by Emile Zola, Upton Sinclair, and John Steinbeck? Is DeForge, perhaps, a better writer or a man with a firmer grasp of the human-ant condition (this is entirely within the realm of possibility I assure you). What exactly does the ant metaphor add to the literature on the subject? Or is that completely irrelevant to our enjoyment?

And what of those who find DeForge less than spectacular you may ask. These are few and far between. In fact I found all of one. Patrick Smith at Spandexless seems almost apologetic that DeForge’s comics don’t work for him. Smith’s review is a strange rambling psychological study in itself:

“…despite my fatigue for these books, I would still recommend them to anyone who might be interested in this kind of thing, because comics as a medium need this kind of work. The fact that it doesn’t work for everyone isn’t so much a point against it as it is a comment on the medium in general… the important thing to remember is that you need to be smart enough to know that something is competently executed and different enough in form that its exciting, but also having enough faith in your own personal taste that despite all that it still doesn’t resonate with you.”

As it happens the best intelligence about Michael DeForge comes from Michael DeForge himself. James Romberger’s interview with the artist at Publishers Weekly is at least a small font of information.

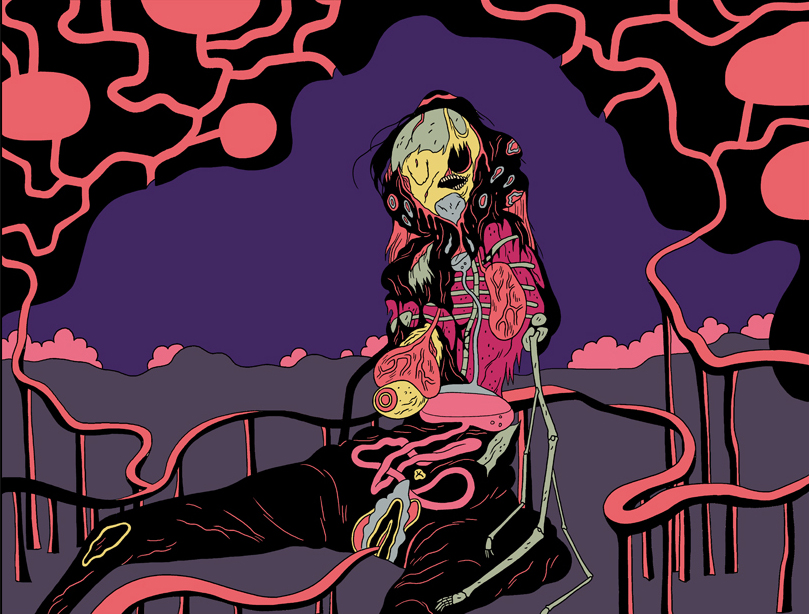

DeForge reveals the influence of silk screen gig posters on his coloring as well as the art of Jack Kirby, Kazuo Umezu, and Hideshi Hino. Drug induced dream states are also said to play a part, a practice which links him to the Undergrounds of old (just in case his art failed to elicit any of these connections):

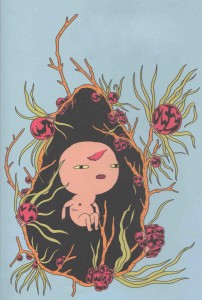

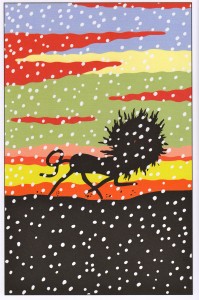

“I want most of my comics to read kind of like dreams, or at least have a kind of dream logic to them, so inducing psychedelic states on the characters probably has to do with that. I haven’t really done a ton of hallucinogens, but I used to shroom a lot, and I was always struck by that buzzing, hyper-defined texture that everything would take on. I usually want my comics to read a bit like that, as if the whole world is filled with a prickly, hostile energy vibrating beneath the surface of everything.”

Of course, none of this tells me why Michael DeForge is the greatest cartoonist of his generation, a description which seems akin to an act of faith if the criticism available is anything to go by.

In most instances, the act of comics evangelism will succeed on the basis of sheer force of will—the overwhelming onslaught of “yay”-sayers. This heretic, however, wants an answer. Can Michael DeForge’s genius be substantiated? Or does it all boil down to the pretty pictures?

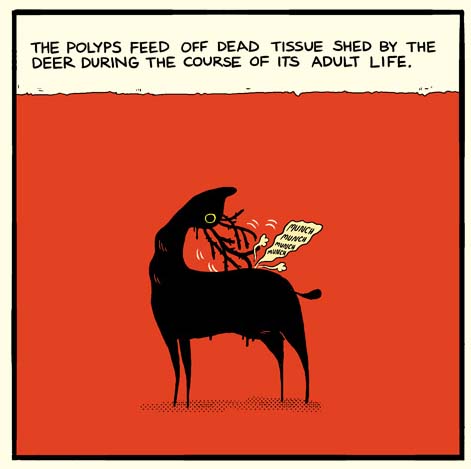

Take, for example, All About The Spotting Deer (read at link) which is easily Deforge’s most accessible work not least because of its narrative clarity and congenial art work. It is a story which has been described numerous times in capsule reviews of Very Casual. The one thing Spotting Deer isn’t though is disgusting or grotesque. DeForge’s construct—a confluence between Bambi and a nematode—would make a fascinatingly creepy but family friendly plush toy (less the penis of course).

Shawn Starr and Joey Aulisio (writing on an obscure blog) provide the longest and best commentary available on this story. For once the substance of the comic which they adore is addressed:

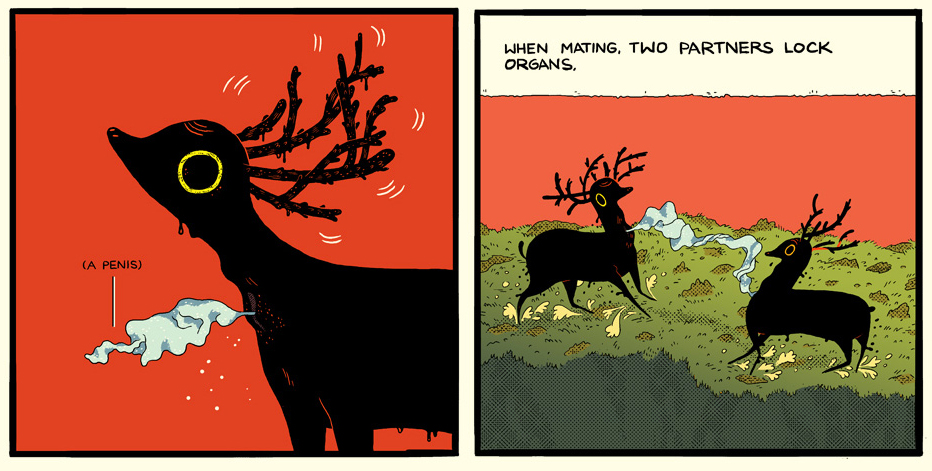

“Starr: All the story beats are there, the uncomfortable section on mating rituals (DeForge’s depiction of the “Sexual Aqueduct” perfectly captures that feeling of awkwardness experienced in a sixth grade classroom) and the oddly nationalistic/hyperbolic statement on the animals importance in popular culture and ecosystem. The book is even designed like an old CRT monitor, and its use of the four panel grid is reminiscent of a slideshow presentation.”

“Aulisio: I have found it difficult to explain why it resonated with me so much…I think DeForge started out trying to make a book savaging the “fanboys” and then by the end realizing he was just like them, which was the real horror of it all. That moment of realization rendered by DeForge is truly chilling, nobody draws disappointment and disgust quite like him.”

“Starr: …I think the “savaging” is too intimate to be from a fanboy. My reading of it is more as an affirmation of DeForge’s place as a cartoonist. He may have started as an outside figure (the writer), but once he (the writer) appears it moves away from the first half’s exploration of “herd” (nerd) culture and becomes explicitly about cartooning.

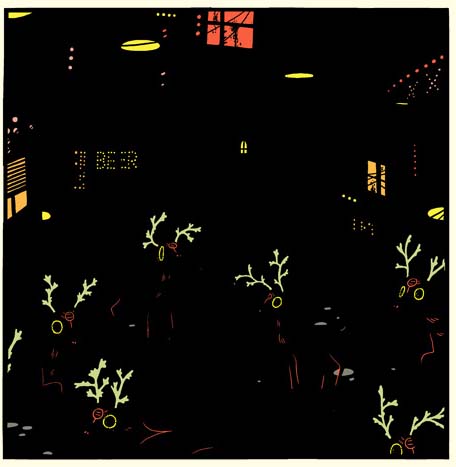

…I think DeForge realized he was one of the spotted deer. A part of the “study group”…there is the “Deer in Society” section, moving away from home to the city (but not before being ostracized by your family/community), the “ink spot” neighborhoods, the livejournal communities and the “pay farms” where their “psychic meat” adapts the characteristics of other products…

DeForge has less to offer on the story but seems convinced that his coloring is purely “ornamental”:

“I think I’ve been coloring my comics the same way I’d go about coloring a poster or illustration—where I’m just trying to make something eye-grabbing, and maybe establish a mood or whatever—so it’s really just decorative. I’m never doing anything I couldn’t accomplish with my black and white comics. So if I do a comic in color again, I want to make sure the colors aren’t just there to be, like, ornamental.”

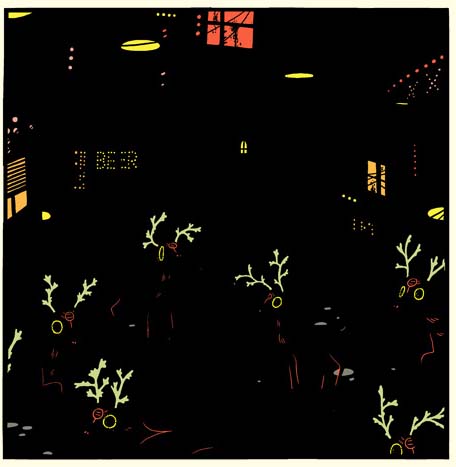

Some of this is apparent right down to the insistent use of what appears to be screentone to vary the color gradients in each panel. There are varying shades of red used to denote sexual activity; a panel blanketed in orange to signal an animal’s sixth sense; and the blue grey tinge of the deer’s penis which suggest less a fleshy protuberance than an extension of seminal fluid. The colors are descriptive, moving from the clear greens of the forest to the more murky environs found in the mechanized cities of Canada. Used as highlights, they add to the sense of desolation and isolation in his depiction of bioluminescent antlers stranded in dark space alongside beer halls and strip clubs.

Spotting Deer is not mere parody of wildlife documentary but (as Starr and Aulisio indicate) a study in anthropology and sociology—a subject now quite familiar to the man on the street in the form of comparisons of human behavior to those of our simian forebears. It is a description of exclusion, exploitation, and half-hearted rehabilitation; a statement on the worm-like ancestry of third class citizenry. Not a simple representation of the dregs of society but a picture of their domestication—benumbed in this instance by soul stripping work and the allure of social networking. A strangely quaint and familiar argument popularly proposed by Noam Chomsky (using the example of sports) in Manufacturing Consent (among other places):

“Take, say, sports — that’s another crucial example of the indoctrination system, in my view. For one thing…it offers people something to pay attention to that’s of no importance.That keeps them from worrying about…things that matter to their lives that they might have some idea of doing something about. And in fact it’s striking to see the intelligence that’s used by ordinary people in [discussions of] sports [as opposed to political and social issues.”

DeForge’s story works best at the convergence of narrative sense and mystery, when the products of deer-dom are suddenly presented to the reader in a hodge podge of styles carefully cultivated by the artist—the detritus of the cultural landscape of the family Cervidae now made real. At this juncture, the story moves from curious amalgamation of mammal and nematode (and host and parasite) to a metaphorical sociology and autobiography. And thus we have sightings of conceptual art, a King Features strip homage, the pixelated nostalgia of a computer game and a quarter bin rock LP.

[Cold Dark Matter-An Exploded View by Cornelia Parker]

A life exploded and examined; all of this enriching and complicating that mystical act of rutting and sex seen some pages before.

Descriptions of DeForge’s work often suggest a visceral or emotional experience not easily communicated but Spotting Deer goes beyond a mere fascination with line and imagery to a more amenable complexity both to mind and eye. The sexual act which DeForge depicts is not between creatures of the opposite sex but between two antlered “males” which happen to be hermaphrodites. Seen in congress with the story’s later developments this becomes not so much a picture of biological procreation but of artistic influence. Acting at once in concert and opposition to this, the antlers begin to resemble genetic fate acting both as tribal headdress and familial enslavement.

If DeForge’s comics lineage can be traced (at least) as far back as the Undergrounds, then one thing is clear—the transgressive is regressive as far as comics are concerned. It has been for decades. The banning of comic books and the jailing of cartoonists may make the headlines but these headlines no longer make for great and lasting art. Not even if you charmingly distort the act of artistic “pregnancy” and transmission, …

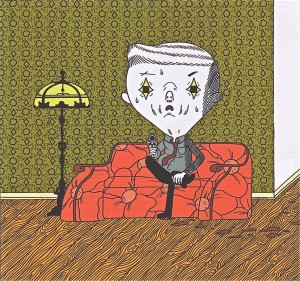

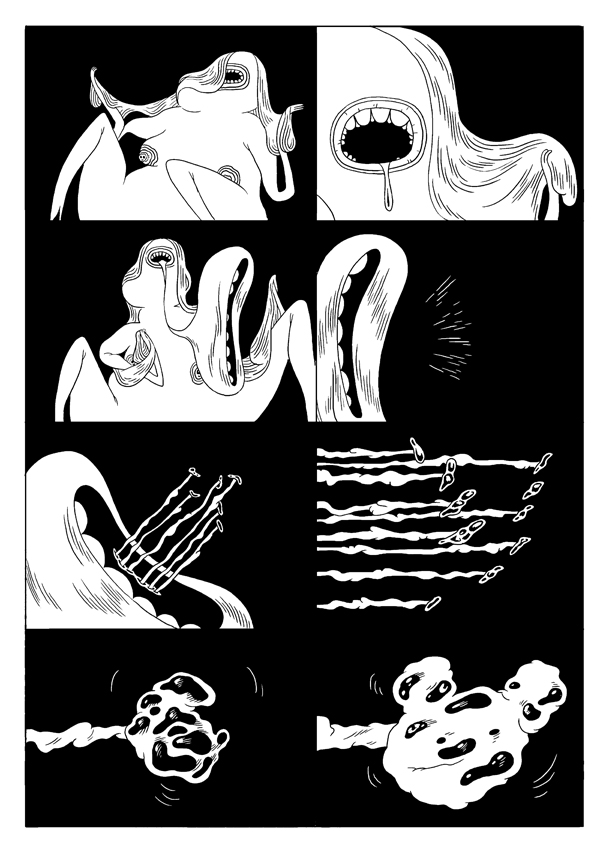

…imagine a drug induced head trip as a cannibalistic ritual, or punk up Dilbert and Nancy and make them Hell’s Angels on a trip to transcendence. These may amuse with their playfulness and herald “promise” in terms of technique but they are not the comics masterpieces we will remember 10 years hence. As much as half of Very Casual is inconsequential fluff with his Ditko “tribute” (“Peter’s Muscle“) taking the rearmost, being nothing less than a veritable time capsule of 80s mini comics drivel. What is required from critics celebrating the works of DeForge I feel is some degree of moderation in praise.

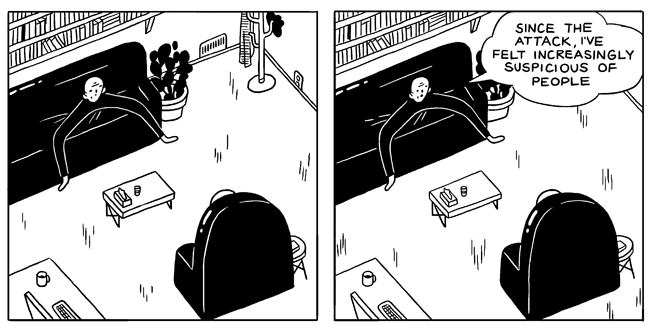

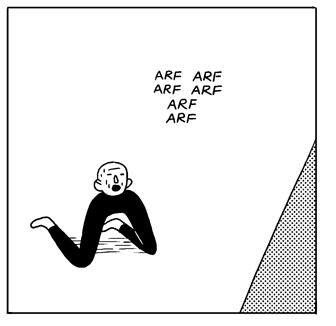

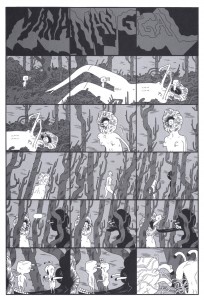

DeForge’s comics certainly seem far removed from the literary structures and complexities—the doublings, the repetitions, the triplings etc.—of the old hands. Despite its length, his Ant Comic largely dispenses with any sustained interplay between word and image or even panel layout.

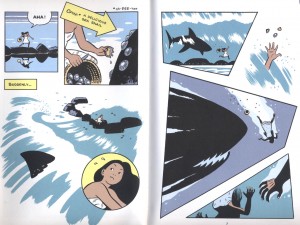

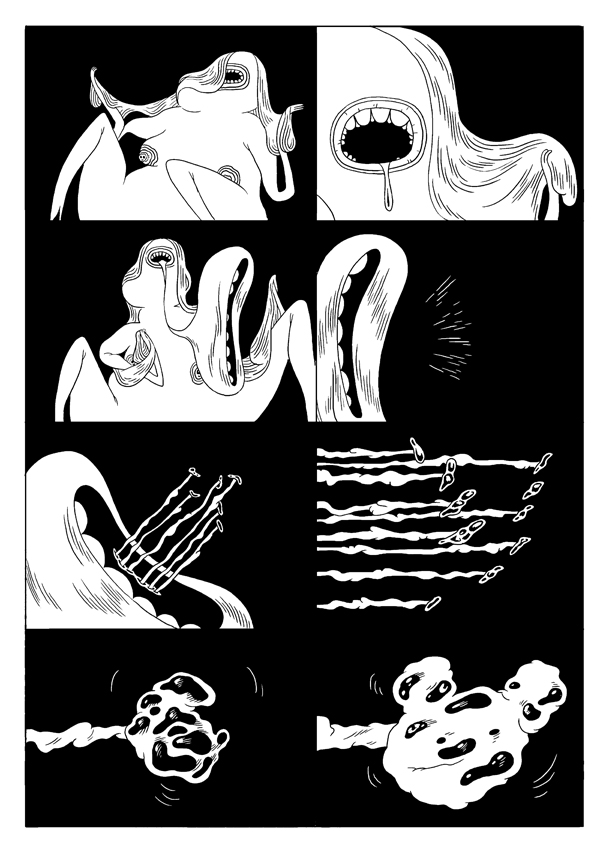

It can be read most directly as an exercise in straight adventure coarsened by bloodless massacres, sudden death, multiple episodes of attempted infanticide, and god-like interventions from humans. In this it resembles Anders Nilsen’s Big Questions where the protagonists are finches. It is differentiated by its greater scientific curiosity and playfulness in design (the architecture of the ant colony, the technicolor queen, the dog spiders). The most appealing pages here impart a kind of primitivization of action; where violence and sexual death are seen as a series of abstractions—shuddering tentacles, puncture wounds, and a pool of blood. A familiar type of comics montage which is enriched by simplicity bordering on abstraction. The dialogue follows a similar path and borders on autism. In its stripped down self-centeredness and solipsisms, Ant Comic mirrors the naked and frankly ridiculous existential angst and egotism of the comics of Mark Beyer (Amy and Jordan) but here grafted to exuberant world building.

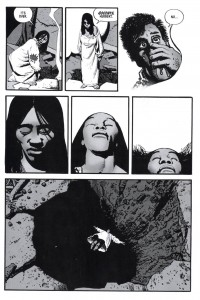

If Ant Comic generates some mood and the occasional flash of deadpan humor, then it should also be said that the gulf between the shock of recognition and our empathy is far too great to be surmounted; a case of technique—the whimsical creature designs and fascination with scale and detail—subverting feeling. It is telling that one of the few instances where any trauma registers is in DeForge’s delineation of the sorrows of war—his callous depiction of the rape and disfigurement of matriarchy (the somatically and anthropologically familiar ant queen).

The natural world and entomology become proxies for an examination of primitive societies, a return to the (seemingly) discredited theories that matriarchies formed a major part of the earliest human societies. It is a refutation of feminist utopias and a proposition that violence is biologically determined both in males and females. Both these themes have been explored quite thoroughly in feminist SF literature (Sheri S. Tepper’s The Gate to Women’s Country comes to mind) but here divested of ornamentation and boiled down to plot points—the matriarchal dystopia as a Sunday adventure strip; the Freudian longing for the mother wedded to a forlorn hope in the figure of a new queen towards the close of the narrative. Nature remains unpredictable; the future unknowable.

DeForge’s tools of reduction and humor bear comparison with the comics of R. Sikoryak as seen in Masterpiece Comics where we are presented with Crime and Punishment as a Batman comic by Dick Sprang, and Kafka’s The Metamorphosis as seen through the artistic tics of Charles Schulz. Even Mozart had his “musical jokes” and DeForge’s Ant Comic presents itself as a kind of artful popularization of martial and feminist themes, one where compulsion, sexual duty, and resurgent gynophobia and misogyny are brought into stark relief.

Taken as a whole, some might see in DeForge’s comics a kind of palate cleanser—primal offerings from the artist’s soul to a comics landscape sick to death of the worked out machinations and literary pretensions of the “heritage” cartoonists; the neglected bigfoot aspects of RAW, Fort Thunder, and Kramer’s Ergot once more brought to the fore even if few long form works of note have emerged from this tradition.

But all this is only guesswork.

As comics readers we have been constantly told what to love without being told how to love or even why to love by the critical community. In this we have a perfect metaphor in the form of DeForge’s Ant Comic where the ant drones directed by invisible hormonal signals congregate dutifully around the queen with a conscientious passion in the service of procreation and survival. And as with DeForge’s fable, the ultimate result of this docile compliance is death.