I first posted this essay on my blog early in 2013, not long after I’d seen Baz Luhrmann’s version of The Great Gatsby. This year I wrote about the Power Records sets again for the zine Towards a Poetics of Man-Bat and for The Los Angeles Review of Books, so I thought it would be fun to revisit this older post. Happy holidays.

_________

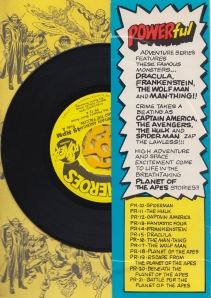

My first exposure to literature—to the “great books” I was asked to study in high school, college, and then in graduate school—came in the form of the book and record sets issued by Power Records in the 1970s.

The cover of Power Records Book and Record Set #12 (dated 1974), adapted from issue #168 of Captain America and the Falcon (Marvel Comics, December 1973), with a cover by Sal Buscema (pencils), John Verpoorten (inks), and John Costanza (letters).

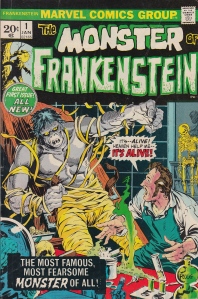

One of my favorites was #14, an adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein written by Gary Friedrich and drawn by Mike Ploog for Marvel Comics. Their comic book version of Shelley’s novel originally appeared in the first few issues of The Monster of Frankenstein, edited by Roy Thomas. Issue #1 has a cover date of January 1973. I was born in late November of 1973.

Issue #1 of The Monster of Frankenstein (Marvel Comics, dated January, 1973). Cover by Mike Ploog.

“It’s fun to read as you hear!” proclaims the copy on the cover of The Monster of Frankenstein, which included a 45 rpm record. At the end of each right-hand page the record would beep, a signal to turn the page to read the next panel. Each set, I realize now, was a radio play. By the late 1970s, radio dramas were already a relic of the 1930s and 1940s, a form of entertainment that had barely survived the 1950s as television took hold as the means of mass communication.

The 45 from my copy of Captain America and the Falcon.

The cover of The Monster of Frankenstein #1 is almost identical to the cover of the Power Records edition of the comic. Both promise a story of “The Most Famous, Most Fearsome Monster of All!” And, as drawn by Mike Ploog, Frankenstein’s creature is a hulking, ferocious presence: his enormous, cinderblock hands reach for his creator. The leather straps that held the creature to the dissection table fail to restrain him. A forlorn skeleton appears in the right-hand corner of the image, waiting for the inevitable struggle between the monster and his creator.

Mike Ploog’s granite-colored antihero is not the John Milton-reading, delicate, misunderstood romantic of Shelley’s text. In a famous sequence from Vol. II, Chapter 6 of Shelley’s novel, the creature stumbles across “a leathern portmanteau” that contains “several articles of dress and some books.” These books include Milton’s Paradise Lost, Plutarch’s Lives, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. In reading these books, Shelley suggests, the monster also learns what it is to be human:

The possession of these treasures gave me extreme delight; I could continually study and exercise my mind upon these histories when my friends were employed in their ordinary occupations. I can hardly describe to you the effect of these books. They produced in me an infinity of new images and ideas that sometimes raised me to ecstasy but more frequently sunk me to the lowest dejection.

When it came time in high school for me to read Frankenstein, I knew what I’d be studying. Friedrich and Ploog’s adaptation, despite the superheroic imagery and action familiar to readers of other Marvel Comics from the 1970s, is generally faithful to the novel.

I think this first exposure to literature in comics form shaped my expectations of the other classic novels assigned in middle school and in high school. I resisted The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby. My father insisted I would enjoy Salinger’s novel if I gave it a chance, but when I asked him to describe it to me, he could not remember the plot.

Most of the novels my middle school teachers recommended were about dogs—White Fang, The Call of the Wild. The Catcher in the Rye, I reasoned, must be about a dog.

Years before I read the novel, I imagined it: a young boy adopts a beautiful, spirited, bright-eyed retriever. They have adventures together. They follow the course of a major American river. They probably hop a train. Or they hitchhike. Later in the novel, the boy and the dog lose each other in a field of corn that sways in bright, clean, Midwestern sunlight. The sky is blue and cloudless as the boy observes his dog walking the field’s perimeter.

I don’t know, I told my dad. I don’t think I want to read about a dog. They always die at the end. Or they get eaten by something.

And, anyway, my family always had cats, not dogs.

The Catcher in the Rye’s oxblood cover was no help. It was blank except for the title and the name of the author. I took this as further proof that Salinger had written a kind of sequel to Old Yeller.

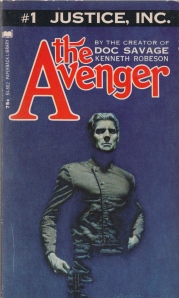

A few years later, I looked forward to reading The Great Gatsby, a novel about a famous escape artist and magician. To conceal his identity, the hero wears a mask and never speaks about his experiences in World War I. The first fifty pages of the novel describe his relationship with Houdini and with Walter Gibson, a pulp writer best known for his work on The Shadow in the 1930s and the 1940s. The Great Gatsby must be some distant relative of Doc Savage, I thought, except Fitzgerald’s hero probably falls in love and, as a consequence, loses his magic powers. He fights off a pack of dogs at the end. There’s always a dog. Also, he wears a gold mask and dresses in purple.

I still cherish my expectations of The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby. What I imagined each novel would be is still more compelling for me than the stories they tell. Some part of my imagination will always insist that The Catcher in the Rye is about a dog and that The Great Gatsby is about a spectacular, handsome, world-weary aviator and magician, sort of like this:

A June, 1972 paperback reprinting of the 1939 debut of pulp hero The Avenger written by Paul Ernst under the Street & Smith house name Kenneth Robeson. Author Lester Dent wrote the popular adventures of Doc Savage under the same pen name.

A friend asked me if Allison and I enjoyed Baz Luhrmann’s recent big-budget adaptation of Fitzgerald’s novel. Yes, I said, but I couldn’t bring myself to admit my disappointment that Luhrmann neglected to include the scene in which Gatsby, having failed to win Daisy’s love, dons his cloak of invisibility and vanishes, only to wash up a few days later on the shore of a volcanic island where he and his agents continue their war against various international crime syndicates.