Last week I wrote a short post about Static Shock in which I argued that the book was mediocre genre product, but that at least it was mediocre genre product that made a gesture at diversity. Better non-racist mediocrity than racist mediocrity, I argued.

I still think that’s more or less the case…but is Static really not racist? It does have a black hero, definitely — but then, there are the black villains.

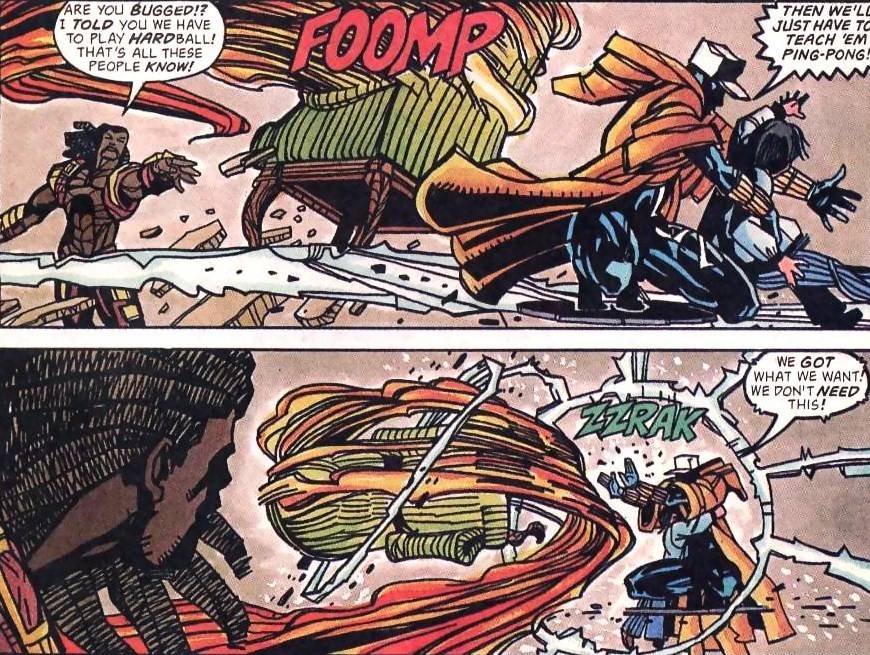

In particular, there’s Holocaust, the evil mastermind behind the first arc. Holocaust is a gangster, but he’s not just a gangster. He’s a gangster with a racial grievance. He tells Static that the hero is insufficiently appreciated. He adds that those on top in the world got there by “luck” — and not just luck, but privilege. “It’s connections. Who you know. Who your daddy knows. It’s birthright.”

But Holocaust, again, is the bad guy. His critique is part of his evilnness. The equality he wants is the opportunity to get cut in on the business of the Mafia; his vision of social justice is equality in the criminal underworld. He’s essentially a right-wing caricature of civil rights advocates; Al Sharpton as brutish, deceitful thug. When Holocaust starts to kill people, Static sees him for what he is, and abandons his evil advisor to return to his superheroic independent battle for law and order. The possibility that law and order might itself be part of a structural inequity is carefully kicked to the curb, revealed to be the seductive philosophy of an untrustworthy supervillain.

You couldn’t ask for a much clearer illustration of J. Lamb’s argument that the superhero genre is at its core anti-black, and that it therefore co-opts efforts at token diversity. The genre default is for law and order. Law and order, in the world outside superhero comics, is inextricable from America’s prison industrial complex and the conflation of black resistance struggles with black criminality. Static, a black hero, is defined as a “hero” only when he aligns himself with the white supremacist vision that sees structural critique as a cynical ruse.

I think it is possible for superhero comics to push back against that vision of heroism to some degree. Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol does in some ways, for example. But Static is hampered by its indifferent quality; it’s not interested, willing, or able to rethink or challenge basic genre pleasures or narratives. Notwithstanding a patina of diversity, it seems like a superhero comic really does need to be better than mediocre if it’s going to provide a meaningful challenge to super-racism.