Franklin Einspruch and Caroline Small have had a lengthy discussion in comments about theory, art, the academy,and related matters. Franklin Einspruch actually reprinted some of it on his blog, but I thought folks might like to see it here as well. (Note that there’s more in comments as well; I’m just hitting the highlights.)

It’s trendy to be anti-academic. Sigh.

It’s not just that. For the last forty years at the picnic of the arts and humanities, academics have been the ants. Leaving aside the increasing systemic failures of college education as a whole described by Jane Jacobs and others, additionally leaving aside the fetid interpersonal culture and political monoculture of academia to which just about anyone ever involved can attest, it tends to revolve around an in-group of indoctrinated adherents given to name-dropping, hair-splitting analysis conducted in a mode that is wholly alien to both art and humanity.

As demonstrated by the fine art world, as academics gain power they make life increasingly impossible for creators who don’t make academic work. The vital phase of every movement of art for the last 150 years took place while the academics of the time were either paying no attention to them or speaking out against them. This is not an accident. Since then academicism has become, by definition, art executed according to a script. Academic criticism judges work based a checklist of vaunted, describable virtues, instead of the intuitive basis where aesthetic pleasure takes place. Lastly, academics and the academically minded who spend enough time assuming a universe in which nothing is inherently true, beautiful, or good finally become unable to make clear discernments about what is false, ugly, and evil, and they act accordingly.

It seems to me that we’re missing a very important point here: Foucault and Derrida aren’t alternatives to Shakespeare et al. Foucault doesn’t send the Panoptican Patrol to snatch the Shakespeare out of your hands. If anything they’re alternatives to Locke and Kant et al. Theory isn’t not some sort of “new thing” in the humanities — it’s just interdisciplinary philosophy. It’s a subject and a discipline in its own right. It’s more like what came before than it is different.

Theory can’t be made into a scapegoat for poor quality work in academia. The crisis in academia isn’t theory’s fault – theory is what academics make of it, what they do with it, like any philosophy is what people make of it. The crisis in academia is the fault of a god-awful publishing structure and a system of tenure that rewards pretty much everything other than public engagement, including evaluating teaching in terms of enrollment and the opinions of 18 year olds, and “responsibility centered management” in university departments, and mass media and the academic versions of the same centralization of capital and influence and the same demographic pandering that’s happened everywhere else in our society.

As for the value of humanities education in the workforce, see paragraph 1. The sentence from the article says: “Graduates need to be able to show the ability to learn something specific and be able to handle that subject’s material knowledgeably and effectively. It doesn’t matter whether that knowledge is in French Literature, Nineteenth-Century Continental Philosophy, Danish History, or medieval music.” That’s absolutely true.

But Twentieth-Century Continental Philosophy, which is loosely what academia uses the shorthand “Theory” to refer to, also belongs on that list. I’ll wager that of the four of us talking here — Matthias, Noah, Mr Kurtzman, and me, I’ve got the most corporate job of any of us, and I’m also the one most steeped in Theory. And that training serves me just fine, because the skills I use when I’m facing down a team of 15 people with four days to produce documentation for a $45M contract offering are curiosity, agility of mind, and the ability to think critically and ask questions. My knowledge of Theory itself doesn’t get in the way of any of those things, and the work I did learning Theory is one of the places I got those skills. If academics fail to teach curiosity, agility, and critical thinking alongside their theory, the problem isn’t theory — it’s those academics and their priorities. Indoctrination isn’t education — but it’s largely irrelevant what you’re being indoctrinated into.

Theories in the humanities are heuristics – engaging with them leads to flexibility of mind through the attempt to reconcile contradictory perspectives and to map their intricate structures against each other. Theory in the humanities doesn’t teach you that Truth doesn’t exist — it teaches you that Truth is incredibly complicated. If all you do is memorize a Theory, believing it to be True, then regurgitate it back, or apply it bluntly and uncritically, you’re missing the point, and probably doing terrible work. BUT THE SAME THING is true if you memorize your chemistry textbook but never ask probing questions, never ask what stoichiometry or thermodynamics have to do with the atomic theory you learned in physics or the ecology you learned in biology. Agility of mind and curiosity is independent of subject matter.

I think the problem isn’t that there’s too little investment in Truth; it’s that there’s too much investment in being right — and in convincing people to believe you’re right for the interest of power, whatever sort of power you’re interested in or entangled in. And you see that investment among people in the humanities, from academics, but also from Creationists, from scientists, from political parties. Blaming that on theory is missing the truths that might actually make a difference.

The academy was just as bad for modernism. When I was down in Augusta last October I chatted with a painter associated with ASU named Philip Morsberger. Phil remembers going into a figure drawing class in the ’50s and getting scolded because his drawings looked too much like the model. Everything was supposed to be abstract, see? Suddenly I understood where all the irritation at Clement Greenberg came from. Greenberg himself was blameless. Droves of lesser practitioners turned the anti-method of modernism as described by Greenberg into a method, and brought it into the classroom. Better students rebelled, which is what real modernism indicates that you should do in the face of an aesthetically enervated method.

This is why I make a distinction between postmodernism and academic postmodernism. Postmodernism is a neutral fact about the intellectual landscape. Academic postmodernism is an aberration. The analogous phenomenon of academic modernism, which has pretty much disappeared at this point, was guilty of creating a similarly stultified creative environment.

So I mostly agree with Caro that we can’t blame Theory for poor academic work, with the caveat that Theory has a mark against it for never having existed outside of academia. Practitioners, not academics, gave us abstract expressionism, comics, jazz, and most of our more interesting creative advances over the last century. Some of those folks may have gone to school or taught at some point in their lives, but Theory is a different sort of thing, one that would have been inconceivable without academia to bring it into being. Academic postmodernism is a survival strategy for academia. And it has certain traits (particularly, stylistic tics) that make it especially suitable for that purpose.

Franklin said: “Theory has a mark against it for never having existed outside of academia. Practitioners, not academics, gave us abstract expressionism, comics, jazz, and most of our more interesting creative advances over the last century.”

Across the disciplines, though, this isn’t entirely true. The body of work that America broadly calls “Theory” was in part created in academic contexts, absolutely, but it was also emergent from the culture of Apollinaire and Bazin and Langlois and Cocteau, and most of all from extremely lively French politics. The French academics who wrote much of this theory weren’t in an academic ivory tower; France has a different sense of public artist and public intellectual than we do. That isolation in the academy that you point to is mostly true just in the US context — where I think the problems you rightly identify with academia have distorted theory just as much as they distort art.

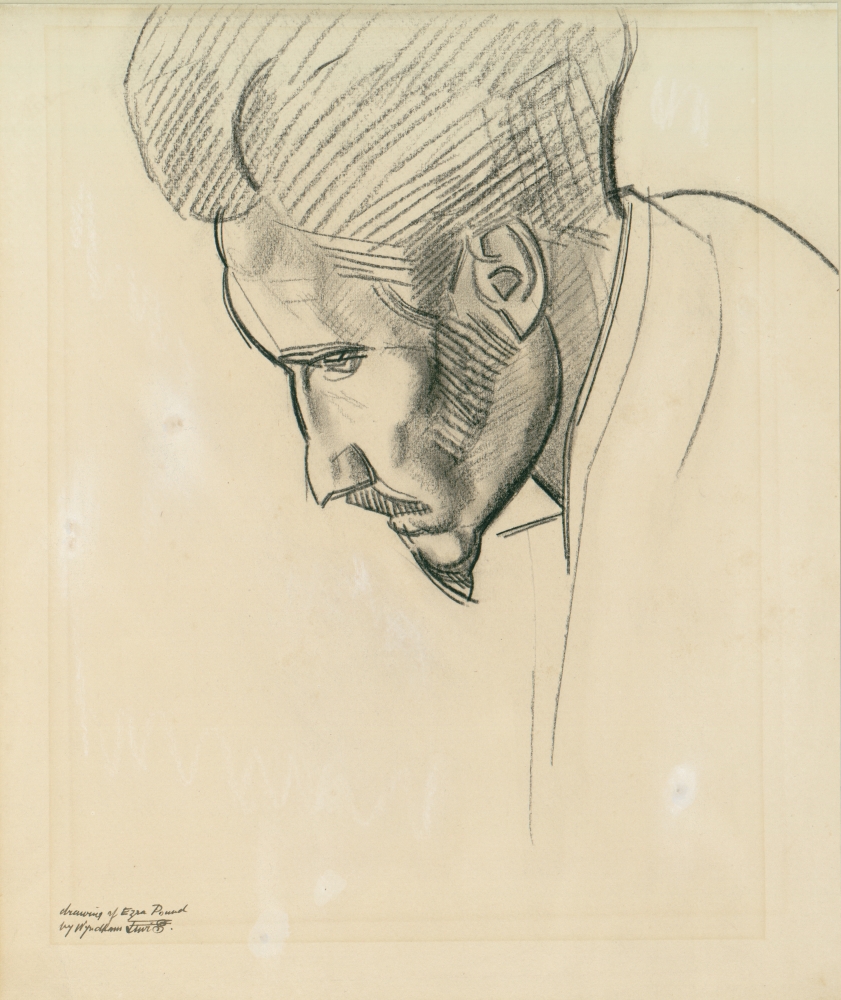

Likewise postmodernism in literature was a movement more like Surrealism or Vorticism in art — a product of practitioners who were also theoreticians. Pound and Wyndham Lewis (who also wrote about visual art), were modernist practitioner/theorists who directly influenced postmodern writing. Postmodernism emerged as much from writers like Burroughs and Ginsberg and Cooper and Beckett and Brecht — from their work and from their ideas about that work — as it did from non-practicing academics writing about them. Practitioners in architecture were grappling with these themes, as were musicians like Schoenberg and Stockhausen and Webern and Philip Glass. Think about the writings of Tzaba or Breton or Borges.

I think a lot of this is just the difference in disciplinary perspectives and cultures; there’s a long tradition in visual art of distaste for “academic art” — but there’s an equally long tradition in letters of the academy providing safe harbor, and stable employment, for experimental writers. More importantly, literary criticism and theory have long been part of the practice of fiction writing. It’s all writing — it’s not as either/or as it is in visual art. So the academy historically has simply not been all that stifling for writers, at least not until recently when the Program has introduced effects and stylistic pressures far more similar to the situation in art. But the Program is, broadly speaking, the least Theoretical environment in academic literature. It’s a different set of pressures, and the sources of those pressures are complex and historically situated, not some straightforward effect of Theory.

Theory’s ascendency in the academy coincided with the academy retreating from public life — but I don’t think that’s simple causality. Culture also became increasingly democratized, less interested in elites and less engaged with history, during the same period. There weren’t really any pressures from outside to prevent the academy from becoming insular and jargony, the way there had been when academics still regularly talked to the public in various wide-reaching forums.

I think there needs to be a careful distinction between “academic” and “theoretical” – because the problems with academic work and academic power aren’t all due to that environment’s comfort with theory, and the particularities of theory aren’t all due to its standing in the academy. It’s possible to tease out elements in academic work that are insular and serve no purpose other than self-perpetuation, but those elements are supported by structural factors like the systems of publishing and tenure. Without care to draw the distinction between the academy and theory, a valuable critique of academic power politics can too easily turn into a kind of knee-jerk anti-intellectualism that polices taste just as much as academic canons and theoretical posturing do.

People should talk about Philip Morsberger more — I have a wonderful book about his work subtitled “A Passion for Painting”: http://www.amazon.com/Philip-Morsberger-Painting-Christopher-Lloyd/dp/1858943760 Delightful stuff. How lucky you were to meet him!

Franklin Einspruch:

Derrida doesn’t literally snatch the Shakespeare out of your mitts. Instead, some boring, tenured potentate dangles a credential in front of your nose and says that you can have it if your Lacanian psychoanalysis of Henry IV sufficiently resembles his. Next thing you know you’re mashing Habibi through the postcolonial sieve with which you puree everything you read.

Ginsburg and Cocteau are hardly the central figures of Theory. Derrida, who is, hardly ever walked off campus from the time he was in his twenties. No, there’s a peculiar tenor to theory that can’t be blamed on academic publishing and tenure, as baleful as they are. What gets published and who gets tenured are not accidental choices, just as this confluence of shitty art and shitty criticism is not an accident. Whatever reasons that academia became “insular and jargony,” the fact remains that Derrida et al. were insular and jargony from the get-go, which serves the purposes of academic survival in a way that, say, romanticism does not.

Charges of anti-intellectualism are the defense of first resort among academics, for obvious reasons. It would be healthy if one of them recognized that turning your discipline into a massive exercise in confirmation bias is not a productive intellectual activity. (Oh look, I just got a press release from the Brooklyn Musuem that reads, “Video Installation Features Dialogue among 150 Diverse Black Men.” Video! Installation! Dialogue! Diversity! Blackness! I think I just had a postmoderngasm.)

Meeting Morsberger was pretty great. I’m selling him short by saying that he’s associated with ASU. He’s the William S. Morris Eminent Scholar in Art, Emeritus at the university, which is an appointment commensurate with international recognition.

Caroline Small:

It’s not that I’m disagreeing with you about the insularity of academic theory, Franklin. I completely agree with your point about confirmation bias — it’s exactly why I left the academy. I just think you’re underemphasizing how much of that insularity was there before 1968, and overstating how much it intrinsically corrupts the particular body of ideas that fall under the rubric of capital-T Theory. As Noah says, Derrida and Lacan and Althusser are not more abstruse than Husserl and Hegel and Koyre. They metastasized out of their disciplinary casing, I suppose, but reading Derrida isn’t that different from reading any other philosopher.

So I guess I just don’t see this tenor to Theory that corrupts it absolutely? Absolute fealty to any theory, especially heuristic ones, at the expense of imagination, is corrupting — but it’s corrupting regardless of the theory.

I think one of the things that gets in my way here is that there’s a distinction in literature between Theory and Postmodernism that doesn’t seem to exist in visual art. Postmodernism in art seems to traffic so much more in axioms than it at least used to in literature. Postmodernism really is an American writers’ movement in a way that Theory isn’t. You’re right that Theory has no organic roots in this country outside of the academy. But postmodernism does. So are you saying that postmodernism has a uniquely academic tenor that corrupts it, or just the Continental stuff? Because maybe what’s throwing me off is just this different perspective.

Ginsberg isn’t really “Theory” in the strict sense, to me — although he and Burroughs really are central figures to postmodernism. To imagine postmodernism without the Beats, without the experimental writers of the ’60s, without Sam Delany and Kathy Acker — I can’t do that. Any “theory” of postmodernism would evaporate without the contributions of those writers. It’s so deeply inmeshed in writing practice to me that I just can’t see it as academic in the same the way you do. I know there’s Theory like Lyotard on postmodernism — but that’s really poststructuralism (which is indeed extremely academic) talking about postmodernism. The fact that the academics eventually wrapped it in jargon as they are wont to do doesn’t negate the 25-odd years when it was a very organic part of American writing and expression.

Not that you’ve ever claimed to be talking about writing, and perhaps postmodernism has played out very differently in art. I just think it’s important not to see Delany and Acker and Burroughs as “academic” writers, especially Acker, who died homeless and very ill without insurance. I only wish the academy could have provided her the same succor in later life that it did to others of her generation.

But the truth is that something similar went on in Theory, if you widen your frame past the American academic version of it: Theory does not have organic roots in the US, but it does have organic roots in France. (Sometime next week I’ll be talking about Althusser and Godard…) Derrida is very much a Johnny-come-lately figure in what we call Theory; he’s just the academic celebrity who put it on the US map. Making Theory about Derrida is like giving Stephen J Gould credit for the theory of evolution — it’s not that Gould has nothing to do with how we understand evolution or how it plays out as a cultural force; it’s that you don’t get the big picture if you put him at the center of your analysis.

In US literature departments, Lacan is actually more central to Theory than Derrida, in truth, as fealty to Derrida is more axiomatic than anything (i.e., the details of his work rarely show up as an influence on any particular reading). Lacan was ejected from the French academy for being too weird. He hung out with Langlois and Godard at the Cinematheque. He was friends with and directly influenced Bunuel and vice versa. He showed up on French talk shows. Foucault and Althusser are probably the most central to Theory in the humanities overall — and although they were indeed academics, they were also involved in French political life in a way that academics in the US never ever are. They weren’t artists, but their work wasn’t ivory tower — it was directly responding to specific political debates and challenges over the status of French Communism after the war and in the wake of Stalinism, and to the realities of French life in the mid-century.

Not to imply that Derrida isn’t academic — Derrida took this constellation of ideas that was very lively, very organic, and very broad-based, he transposed it into an immensely esoteric philosophical context, and then he exported THAT to American universities. And Americans looked at the export and said “that’s the real thing, baby!” But it was actually pasteurized and homogenized in that uniquely academic way because the US doesn’t let raw food through customs, and because Americans, even academic Americans, especially academics in English departments which led the Theoretical charge, tend to be both romantically attracted to and slightly befuddled by politics in foreign languages.

I’m 100% behind your critique of the pasteurized, homogenized export and the way it’s been a bludgeon in the hands of people with incredibly self-serving and insidious interests. I left the academy because, in my opinion, the environment was every bit as stifling to imaginative, meaningful, engaged THEORETICAL work as it (apparently) is to imaginative, meaningful, engaged artistic work. But the solution to that isn’t to enforce some kind of artificial boundary where theory belongs in and to the academy and art belongs to the world. Those are incredibly false distinctions that lead precisely to the kind of theory you don’t like, and in the process aid and abet the power structures of the academy. Nobody wins there.

What do you think of a writer/philosopher like Sartre? Is he also corrupt in this academic way, because he’s revered in the academy and because he wrote both fiction and theory? He’s something of an archetype of the French intellectual tradition to me, and I think his influence on the emergence of Theory in France, especially his influence on the type of conversations these thinkers had with each other and with the society and his importance in establishing the context for the intellectual foment of France in the 1960s, is terribly underemphasized by academics, partly because he stands as a demand for public engagement that academics do not want to be responsible to.

Or Zizek, for example, who when slammed for writing copy for Abercrombie and Fitch magazine, replied “If I were asked to choose between doing things like this to earn money and becoming fully employed as an American academic, kissing ass to get a tenured post, I would with pleasure choose writing for such journals!” That’s the same spirit I think you’re seeing in and asking from artists — but there’s hardly anybody in existence who is more Theoretical than Zizek. Does he just not count because his imagination is analytical rather than expressive?