This first ran on Splice Today.

___________

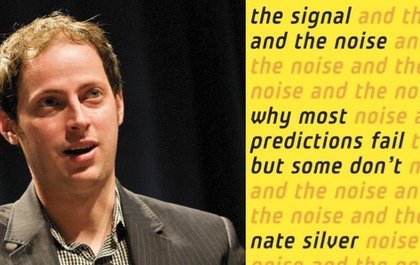

Nate Silver’s The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail — But Some Don’t appears, at first glance, to be a guide to better wonkitude. In fact, though, it’s something of considerably more interest — an argument for how and why predictions are central to creating a better world. The good is predicated upon good prediction — which means that (though Silver never explicitly says as much) forecasting is not just a skill, but is a moral act. The Signal and the Noise, then, somewhat surprisingly, is as much a guide to ethics as a guide to statistics — or, perhaps more accurately, is a guide which suggests that you cannot do ethics without statistics, and vice versa.

Silver is best known for his political prediction site, fivethirtyeight, which has become legendary over the last four years for its success in calling Presidential and Senate elections. He’s also well known for using baseball statistics to predict player performance, and or his moderate success as an online poker player. Silver spends time discussing all of these endeavors, None of these endeavors seem to have much of a moral content — but Silver’s book also focuses on other venues for prediction where the virtue of getting things right translates more easily into virtue, period. Predicting hurricanes, earthquakes, or terrorist attacks all have obvious and large scale effects on many, many people. Similarly, evaluating the probability of climate change is hugely important for just about everyone on the planet.

How, then, can we improve predictions? Silver offers a number of suggestions — but the most important boil down, perhaps, to a willingness to acknowledge how hard it is to improve predictions. Silver divides forecasters into two groups: hedgehogs and foxes. Hedgehogs for Silver are people with a single big idea, which they stick to tenaciously. Foxes, on the other hand, are uncertain, eclectic, and willing to change their minds. Hedgehogs have grand theories; foxes limited hypothesis. Hedgehogs believe in their models; foxes don’t trust theirs. Hedgehogs pronounce and then confidently demonstrate how the data fit their pronouncements; foxes look at the data first, and then, cautiously and with many reservations, try to see if there is a pattern.

Hedgehogs, Silver argues, are more likely to be interviewed on talk shows or get quoted in the press, because they’re the ones likely to make shocking and exciting predictions that garner big headlines. You’re more likely to sell books if you declaim that the US will definitely face a major flu pandemic in the next 10 years which will kill millions. But you’re more likely to be right if our claims are less ostentatious and more foxy — if you admit, for example, that flu pandemics are hard to predict, and that the likelihood of a deadly outbreak is tricky to measure with certainty, which is why (as Silver reports) many flu scares in the past have failed to pan out.

Foxes, Silver says, need in particular to acknowledge and understand their own biases. The idea here is adamantly not to eliminate biases, which Silver suggests is impossible, and probably not even desirable. Instead, it’s to make explicit where the forecaster is coming from — to figure out what the forecaster is assuming (based on common sense, expert knowledge, rules of thumb, or even rank ideology) before she makes her prediction.

This is in part why Silver (and most other statisticians) advocate Bayesian reasoning. In Bayesian reasoning, a forecaster begins by stating her own estimate of an events probability, and then adjusting that probability on the basis of subsequent evidence and events. Bayesian reasoning, in other words, forces a forecaster to admit to her own prior biases, and then test those biases against what actually happens.

To be a foxy Bayesian, then, is to be possessed of humility and honesty — particularly self-honesty. These are obviously important virtues in most moral systems, and Silver is entirely convincing when he claims that they are vital to the art of prediction.

A funny thing happens, though, when humility and honesty are instrumentalized as part of the predictive process. Specifically, it ceases to be clear that humility is humility, that honesty is honesty, or that either are particularly virtuous. Thus, for example, Silver’s enumeration of the virtues of foxes is pretty clearly an enumeration of his own virtues — he is the fox, pointing out the flaws in all those arrogant hedgehogs. This isn’t necessarily a problem for his arguments per se — but it does give that section of the book an unpleasant air of self-vaunting.

More consequential, perhaps, is Silver’s discussion of the great poker player Tom Dwan. Silver is clearly extremely impressed with Dwan, and singles him out as an exceptionally good poker player — which means, specifically, an exceptionally honest one. Dwan “profits,” Silver says, “because his opponents are too sure of themselves.” Dwan, on the other hand, is great in large part because he knows how great he isn’t. “‘Poker is all about people who think they’re favorites when they’re not,'” Silver quotes Dwan as saying. “‘People can have some pretty deluded views on poker.'”

So, again, Dwan’s strengths are the virtues of honesty and humility — and he uses those virtues to make a living by preying on the weak. Silver explains that the weakest players in poker support all those above them in the pecking order. If you’re making money in poker, it’s almost certainly because there are people in the game who don’t know what they’re doing — who think they are far better than they are, who are deluding themselves, who don’t know how to play. Dwan’s virtues — and Silver’s, when he was playing poker professionally — allow them to make rational predictions, and thereby to systematically take advantage of the less virtuous/clever. Improving predictions here seems less like a way to improve the lot of humankind, and more like a way to create a more perfectly rapacious capitalism.

“Presuming you are a betting man, as I am,” Silver writes at one point, “what good is a prediction if you aren’t willing to put money on it?” It’s a telling formulation, seamlessly linking money, predictions, and goodness. For Silver, the sign of virtue and value is money — the marker of success. Honesty and humility are worthwhile because they lead to results — and you can measure those results best through cash.

The problem here is not that Silver is wrong. On the contrary, the problem is that he’s right. His moral vision is, for all intents and purposes, the moral vision that matters. His algorithm — greater virtue -> progress -> good-certified-by-money — is as close to a consensus ethical vision as we’ve got. Refine our tools, increase our knowledge, improve our lives, if only incrementally. That’s how modernity works.

It’s certainly an attractive vision, and not one that anyone can oppose categorically. Who wouldn’t like better foreknowledge of earthquakes or disease outbreaks? Yet, at the same time, it might be worth remembering that controlling our lives and living a good life are not necessarily the same thing. They can even, in some cases, be opposed. A world of foxes is not a heaven if those foxes are all intent on devouring each other. Silver would be the first to say that we will never know the future. His solution — and it is a moral solution — is that we should work hard at predicting it just a little better and a little better. Perhaps, though, in addition to becoming more and more powerful predictors, we might devote some time to thinking about how, in a world where our future is uncertain and our power limited, we can best treat each other not as foxes or hedgehogs, but as human beings.