This is the last in a roundtable on Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series. There’s lots of good stuff in the previous posts (too much good stuff, perhaps, but such is the danger of going last). If you haven’t already, take a look at:

Noah’s “Dream Lovers,” Suat’s “Impressions of Sandman,” Tom’s “Post-modern Something,” and Vom Marlowe’s “Revisiting Old Lives.”

****

Like everyone else in the world, I loved Sandman when it first came out. I have all the collected volumes but one (more on that later), and while I haven’t reread any of them, I do still think of some of the stories and characters sometimes. (Which would especially impress you if you had any idea of the mental chaos I fight daily just to remember to, say, eat lunch – although if you’ve followed Gluey Tart at all, you no doubt do have some idea.) So, I remember the whole thing fondly but was a bit worried that stirring it up again would just make everyone unhappy, like visiting my home town or listening to ‘80s Aerosmith (and ‘90s or, quelle horreur, ‘00s Aerosmith is obviously not even on the table).

Mostly, though, I was just excited about figuring out where the hell that enormous stack of Sandman books was and digging in. On top of a bookcase, it turned out, and not under a huge, dusty, towering stack of God knows what, like almost everything else I look for. And I realize that there are books on top of these stacks, and everything can’t always actually be on the bottom, but sometimes I wonder if they don’t migrate there on their own, trying to hide from me – something that could easily happen in Sandman, now that I think about it. I decided to look at the two Orpheus stories because I particularly liked those. (They’re in Fables and Reflections and Brief Lives, if you’d like to read them yourself.) Or maybe I’d pick something else – I didn’t know. (I often don’t; I prefer to think of it as being flexible.) But I flipped through the books in order and, good lord, that is some lousy-ass art. I mean, a jittery, shifting every few pages, unnervingly bad collection of art. A Game of You is the worst – that one doesn’t just make me just cringe but also makes me fucking angry about its really excessive badness. I kept thinking no, this is really so bad I can’t quite bring myself to spend quality time with it.

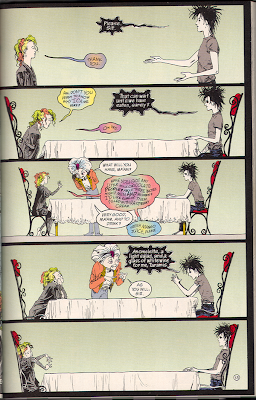

I remember having problems with a lot of the art in Sandman the first time around – the overall quality (by which I mean the lack thereof), but also the startling shifts in style and character design in mid-arc. Like these three consecutive pages:

No, of course it isn’t all horrible. (I like two of the those last three pages, and don’t mind the other.) But a lot of it is. And if it bothered me then, it freaks me the hell out now, having since discovered manga and becoming accustomed to the joys of consistency and artistic whatsit. So I riffled through every volume until I found one that I liked the look of pretty consistently.

Unfortunately, that volume was the second to the last, The Kindly Ones. This is unfortunate in several respects:

1) It is an endgame sort of volume that heavily references and wraps up a number of previous storylines, few of which I remembered as well as I needed to.

2) Morpheus fucking dies. I hate that.

3) See point 1. This collection isn’t boring, but it does feel like more of a settling of accounts than an exciting bit of fantasy, and you kind of have to read the whole thing – there isn’t a shorter piece that holds up on its own in this volume.

4) Morpheus dies. Did I mention that already? I loved Morpheus, in all his enigmatic, usually barely there but always wonderfully Goth manifestations. Morpheus dying is counter to my personal agenda.

Let us tackle these points in order, you and I.

1) Reading Sandman always reminded me of reading Ezra Pound, except that I like Neil Gaiman, while I always sort of wanted to kick Ezra Pound’s ass. What I mean is that Gaiman throws in all these allusions to various mythological and historical high points, and you won’t really understand what’s going on if you don’t get those connections – much like Pound, of course, but ramped down a couple hundred decibels. Gaiman doesn’t reference anything really obscure, and, you know, nothing’s actually written in Greek. So that puts it in a whole other and hugely more acceptable level of pretentiousness right there. Also, Gaiman has so much fun with it, you wind up having fun with it, too. It isn’t “See ye these literary allusions and weep in terror at my big old brain.” It’s more like, “Oh, my God, and then the ravens, the ravens are so cool, and wait, wait, Loki! See what I did there! Oh that’s so cool! And that could tie in with…”

2) I was, and remain, in love with Morpheus. He was written beautifully, if not always drawn beautifully. He is ambiguous – his relationships with the other characters aren’t often clear, or his motivations, or his intent. I often want to scream at writers to please shut up – stop telling me about the damned character. I don’t need to know everything. I want there to be some mystery in our relationship, just like in real life. It’s hard to retain the ambiguity and keep hold of the character, I know – too much information and you feel like a six-year-old has been tugging at your arm and filling you in on all the complexities of the Transformers for several hours; too little information and you don’t care because you never connected with the character in the first place. More people should try, though. Reading Sandman might help.

Morpheus talks a lot about the rules, and the following thereof, and the doing of what must be done. A beautiful example of this is the action that drives the last nail in his coffin. He gives Nuala a pendant when she leaves the Dreaming, telling her he’ll come if she calls him. To grant a boon of some sort. This is one of the many complicated plot points that lead directly to Morpheus’ death. I’m not saying much about any of them because who has the time? This one, though, might bear some explication. Nuala, a fairie who’d been given to Dream in an earlier story, loves Morpheus and mopes around a lot, pining for him. When her brother shows up unexpectedly to take her back to Fairie, she lets Morpheus decide if she stays or goes. He cuts her loose. As a result, later, when Nuala learns Morpheus is in trouble, she summons him – at the worst possible time – hoping to save him by getting him to stay with her. By asking him to love her. Well, who hasn’t had the impulse? It never works for any of us, and Nuala is no exception. This is all very poignant, etc. etc. What I love about it is that Morpheus comes when she calls him. The Dreaming is being pulled down around his ears, but he’d be safe if he stayed put. He tells her the timing sucks, but when she insists, he goes, knowing the furies will take the Dreaming in his absence. I don’t love this because, oh, it’s so romantic (wibble wibble). I mean, it’s hard not to be annoyed with both of them, on that level. I love it because I believe Morpheus when he gives his reason for doing it – there are rules, and they must be followed. Some might say, well, perhaps an exception might be made in this case. I see the logic, but I’m utterly charmed by Morpheus’ failure to compromise. I have a great deal of sympathy for that position. Of course, he sort of does become someone else in the end, anyway. But it’s all, you know. Ambiguous.

3) The Kindly Ones isn’t the most exciting Sandman collection, but it is still fantastic fantasy. It’s the kind of thing you read on the train for fifteen minutes, and then you get off the train downtown and walk onto the dimly lit platform and start looking around for Norse gods or sentient crows or faeries or something.

4) Morpheus’ death comes as no surprise. There’s a lot of foreshadowing in all shades from really obscure to ham-fisted like an ultra-conservative Republican state representative, but it’s still a shock when it happens. I like the way it’s portrayed, too. A light flashes, and goes out. And Dream the Endless is gone. And everything else goes on. Which is just exactly how death works.

Whenever Death (the character) tells someone they got what everybody gets – a lifetime – I think of the Stephen Crane story, “The Open Boat.” The theme of that story being, basically, “it is what it is.” The tie-in is obvious: nature doesn’t care, and death does her job, because that’s what she is. In The Kindly Ones, Morpheus talked a lot about fulfilling his responsibilities, and many characters questioned his motives. Did you do this on purpose? Do you want to die? One of the many bits of foreshadowing comes via Loki, a divine trickster, but not in a fun, gentle, let’s exploit Native American legends and wear dream-catcher earrings sort of way. Morpheus is the reason Loki is out in the world and wreaking havoc (on Morpheus, as it turns out) instead of being tied by his son’s entrails under the earth with snake venom dripping down on him for eternity, where he belongs. The Corinthian (sort of the ultimate walking nightmare, which Morpheus recreates toward the beginning of this collection) steals Loki’s eyes and breaks his neck, and Odin and Thor take Loki back to the underworld to tie him back down. Loki tries to get the dim-witted Thor to kill him, but Odin intervenes, and Loki isn’t able to escape his fate worse than death. Because Loki is a god, and that’s what’s proper. Morpheus (who is not a god, but the distinction is – well, indistinct) is able to escape, though. What does that mean? I don’t know. That’s how death works, too.

I refused to read the last Sandman collection, The Wake, when it came out. At the end of The Kindly Ones, another character takes over the dreaming (Daniel, who’s never done anything to me, but I hate him anyway – see points 2 and 4 – even though he becomes basically a new version of Morpheus – but it’s sort of like reincarnation in Buddhism, where the flame goes out, and the flame is reignited, but it’s not really the same flame). Sandman was about Morpheus for me, and when Morpheus died, I didn’t want anything else to do with it. Which was really quite emo of me. But it’s also a testament to what Neil Gaiman did with this series, even saddled with a collection of crappy art he had to drag around behind him like the rotting carcass of a castrated ox (or some other foul, unwieldy dead ungulate of your choice). I hesitate to use the “t” word, but in Sandman, Neil Gaiman created something transcendent, in its way. Not “I’m going hire a lawyer to help me set up a religion” transcendent, but something that somewhat extends the limits of ordinary experience.