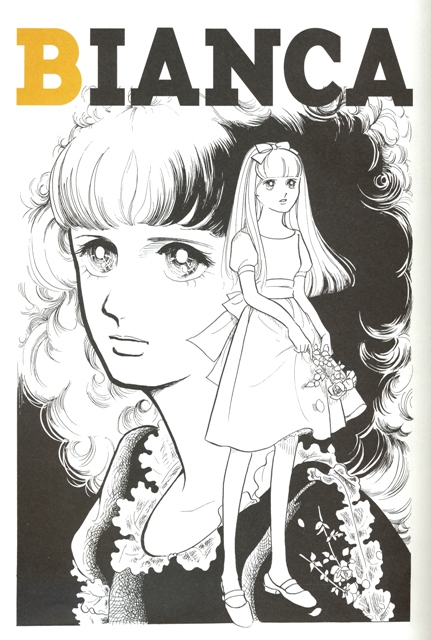

(Update: Should have noted this earlier: you can read a pdf of Moto Hagio’s Bianca here.

1.

In his first column for the new tcj.com, Ken Parille discusses Moto Hagio’s story Bianca. Ken says that the first time he read the story he was not very impressed. However, he says, he decided to try reading it over and over to see if it grew on him. And so it did.

What’s most interesting to me is the way Hagio carefully sets up the story to appeal to child readers, in this case, young girls. The central tension that animates “Bianca” is found throughout children’s fiction, especially fairy tales: hostility toward authority figures, such as parents, other adults, and even older children or siblings. Within the logic of such tales, the young child is often an innocent under assault by the actions and beliefs of manipulative older characters. Such stories dramatize a wish-fulfillment fantasy for the reader, who is imaginatively allowed to punish an authority figure, occasionally even committing fantasy patricide or matricide. We see this in tales like “Hansel and Gretel,” in which the evil step-mother, who had abandoned the title characters in the forest, mysteriously dies at the end, just in time to be deprived of wealth the children had taken from the witch, the step-mother’s doppelganger. Identifying strongly with the abused child characters, the reader (who likely resents authority figures who control her) might experience the death of both women as a fulfillment of a kind of revenge fantasy. In “Bianca” revenge is the real theme, enacted, as we will see, on Bianca’s cousin Clara.

Ken goes on to work through the structural contrast between nature (child) and civilization (adult). He concludes (as the above indicates) that Clara, the narrator, is on the side of civilization, and that Bianca is on the side of nature. Where other readers (like Kate Dacey) have seen Clara as allied with Bianca, Ken sees them as opposed. Or as he says:

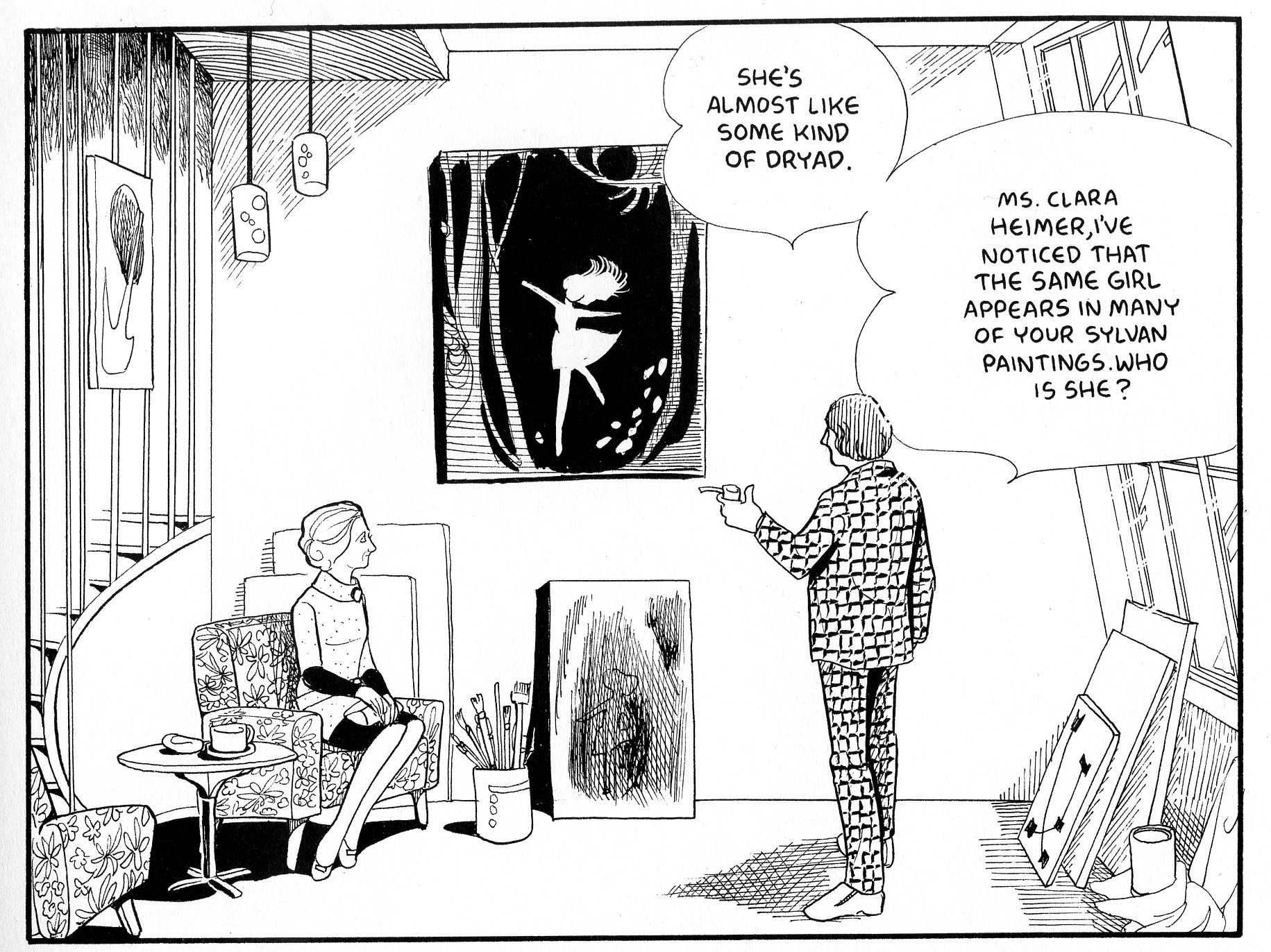

Yet Clara’s paintings also seem false: every one idealizes Bianca, turning her into a cliché: a perfectly posed dancing ballerina. Clara caused her cousin pain, but she avoids representing this pain in her art. Perhaps Clara learned nothing from her short time with Bianca. Decades later, she still sits in the house (an imprisoned gothic victim?), creating paintings that are a whitewash, that erase all signs of her guilt and complicity. Is Hagio aware that Clara’s art shows none of the complexities and none of the darkness that “Bianca” does? As an artist of the child psyche, Clara is a charlatan compared to Hagio.

This is a stimulating and thoughtful review. I still disagree with it though!

In fact, Ken’s essay is an interesting object-lesson in the dangers of academic criticism. You can find tension and structure in any narrative. The longer you look, the more structure you’ll see; we’re meaning-making creatures. So then, is the point of criticism just to see whether you can play with that structure? Is the goal of evaluation to declare that you have done so? Ken does relate his structure to other ideas (childhood paranoia, fairy tales — lots of things) but his evaluative criteria pretty much all come back to, “look! structure!” Or as he puts it at the end of his essay:

It’s a sentimental-gothic fantasy that plays into a child’s paranoia about elders. And it’s fascinating.

Sentimental-gothic fantasies that play on paranoia aren’t all that original or special. Ken admits elsewhere in the essay that the handling of those themes here is “straightforward” rather than more ambivalent or complex (as Nicole Ruddick had argued). So by Ken’s own admission, we have a familiar binary between nature and culture presented in a straightforward way. Why is that interesting? Nothing in his essay really answers that question.

2.

I’d also argue that Ken’s binary take on the story leaves a lot out. For example, Ken overemphasizes the tension between Clara and Bianca. For Ken, as noted above, Clara is civilization, Bianca is innocent nature. But are they really so separable? They’re cousins after all…and Ken notes that they’re difficult to tell apart visually. They’re parallel. Indeed, it’s possible, without too much difficulty (and in light of Hagio’s story Hanshin) to see them as the same person. Bianca, who becomes adult Clara’s soul and inspiration, could be seen metaphorically as simply Clara’s youth — her younger, freer self. Certainly, she’s an aspect of Clara; her complement, not her antithesis.

In that vein, I don’t see anything in the story that undermines Clara as strongly as Ken wants her to be undermined. Ken above insists that Clara’s paintings are empty and trite. From this Ken concludes that Clara does not understand Bianca’s true conflicted nature.

There’s another, simpler explanation for why Clara’s paintings are cliched and saccharine, though. It’s because they look like Hagio’s drawings! In fact, Clara’s paintings seem more ambivalent than Hagio’s, if anything.

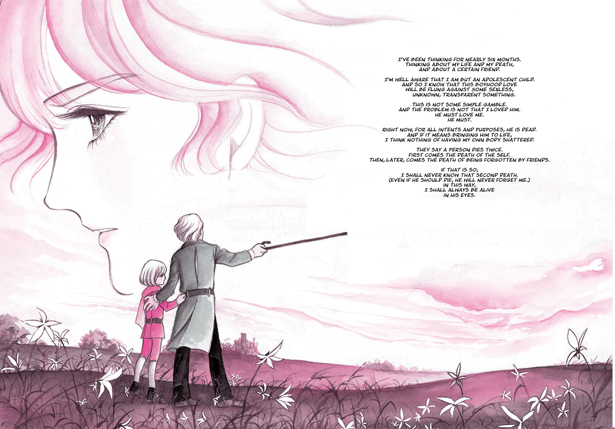

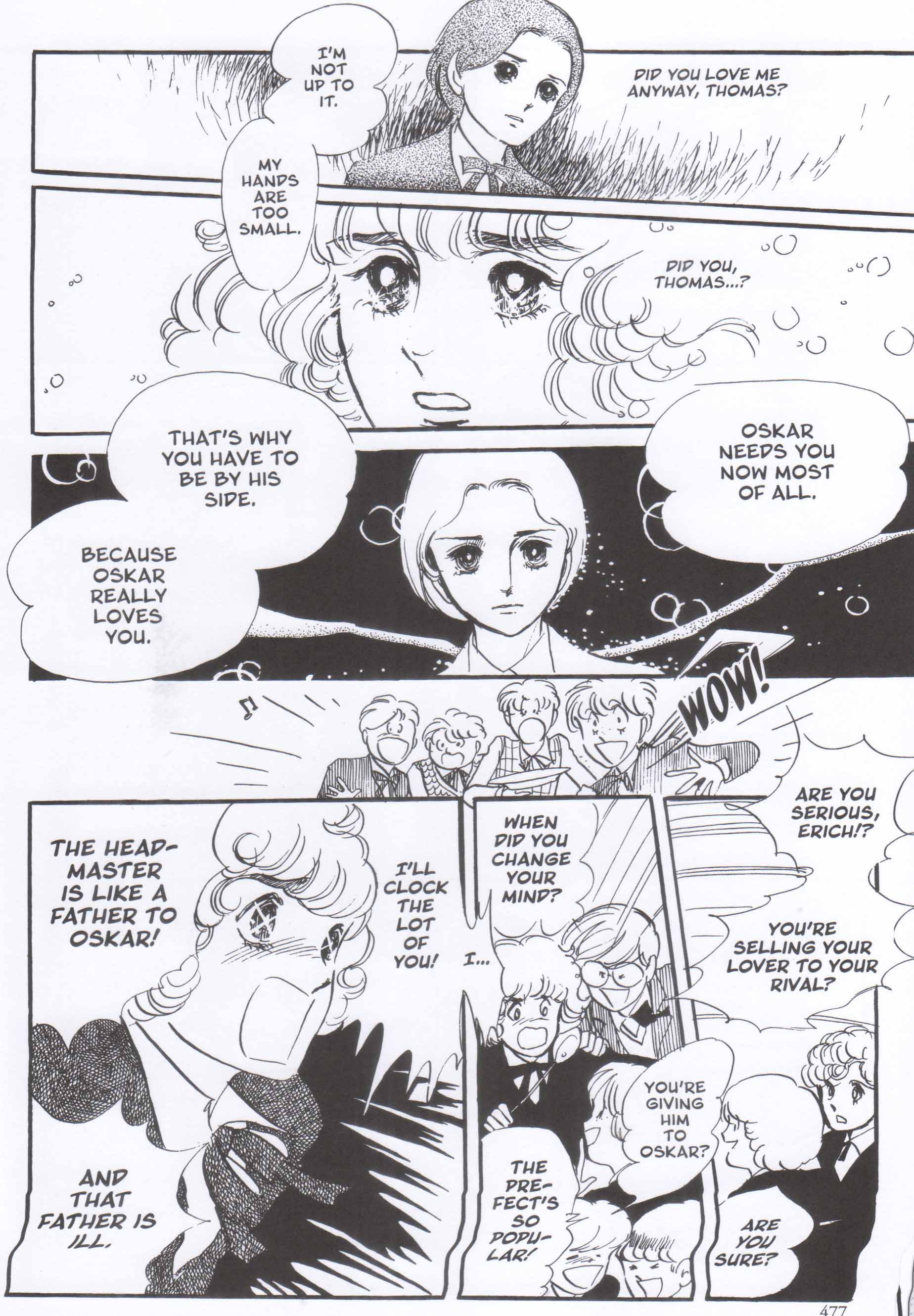

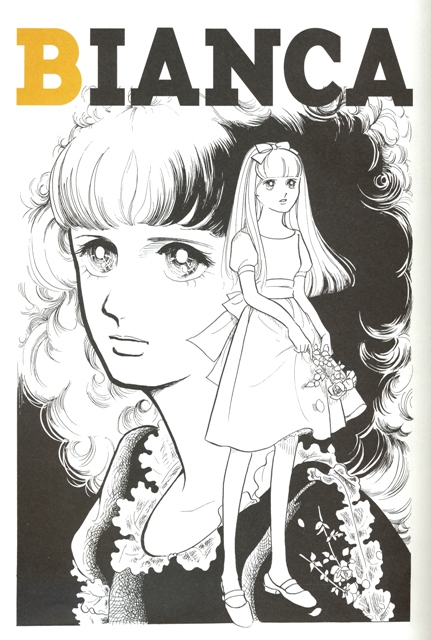

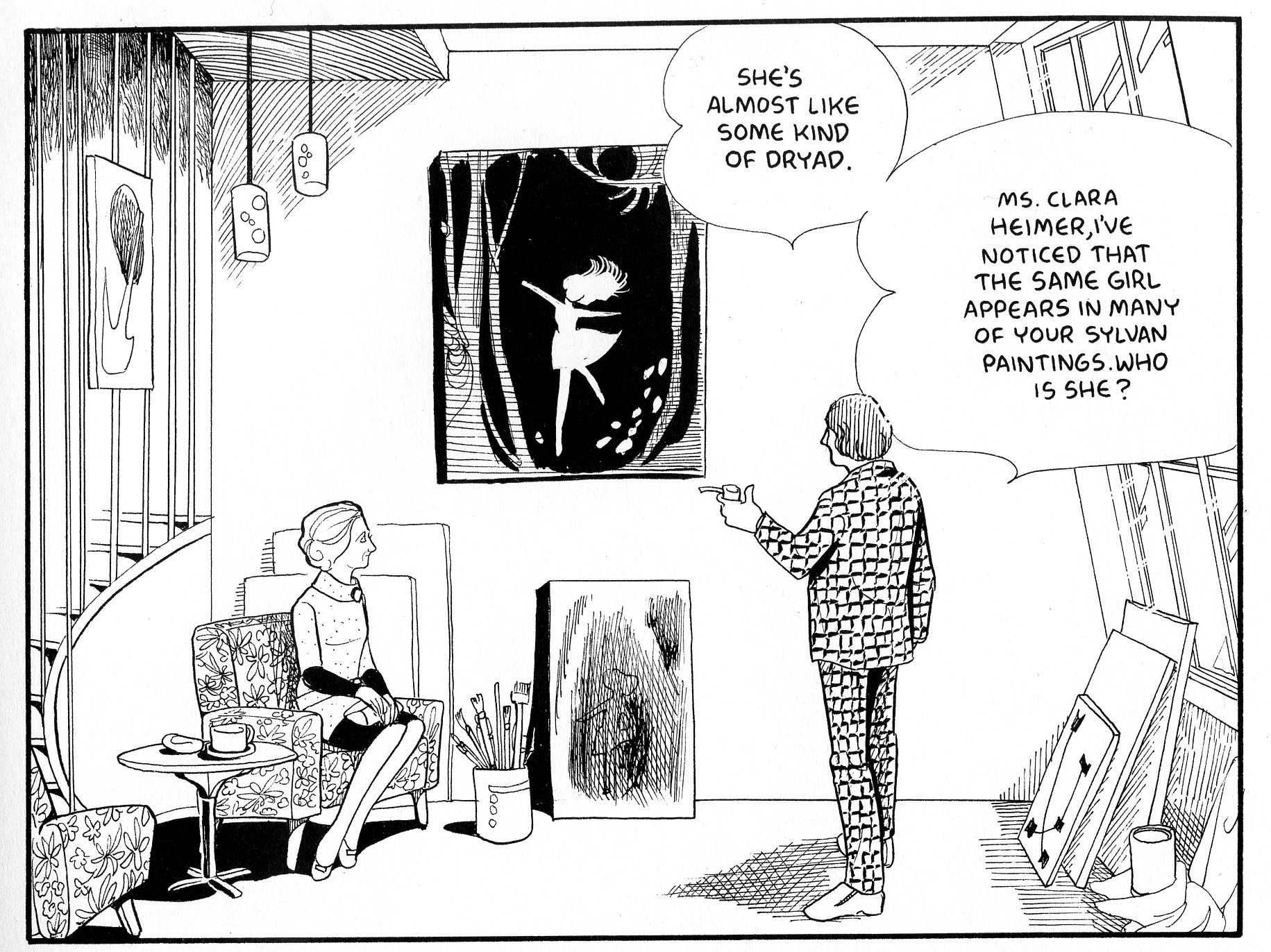

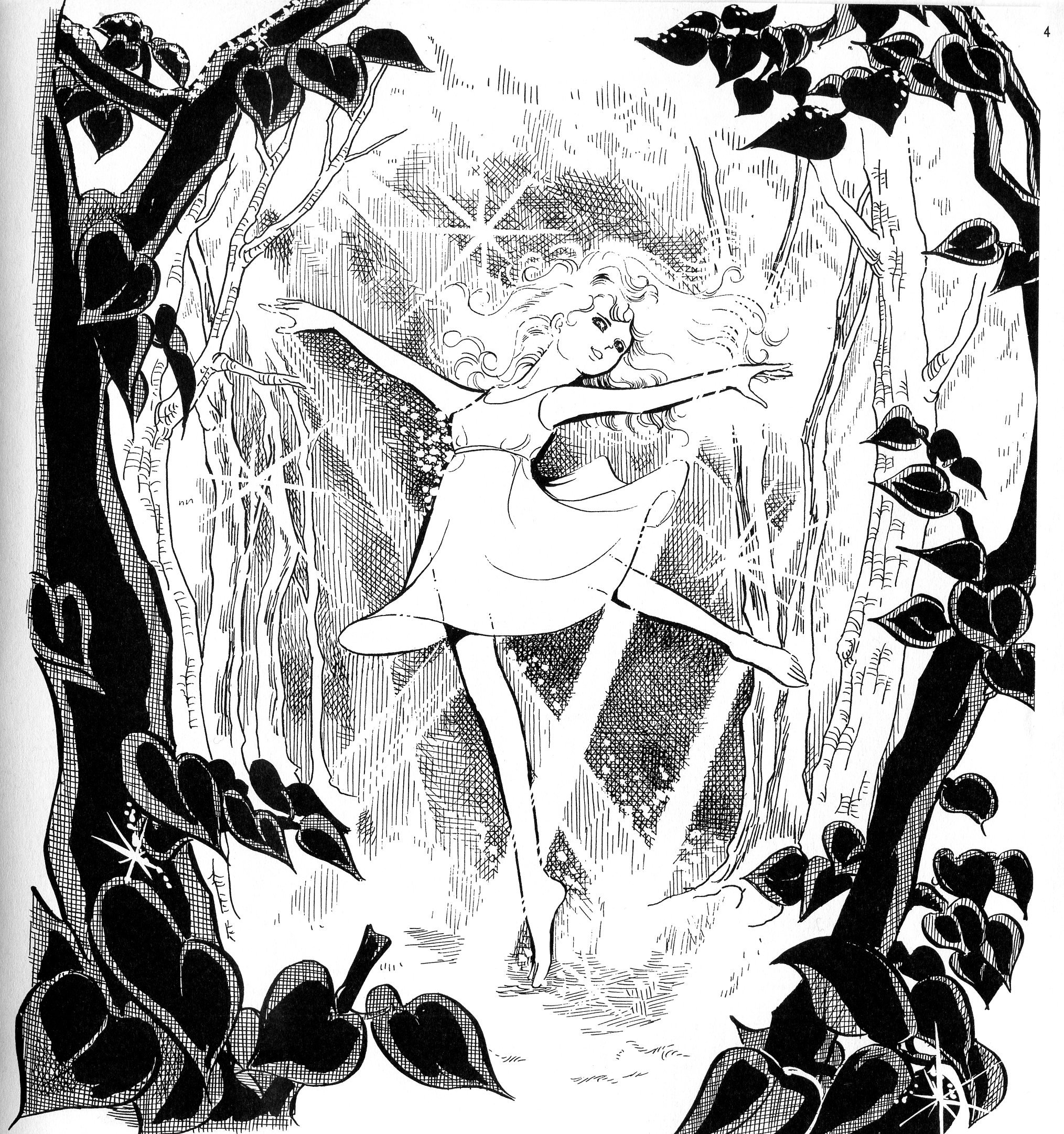

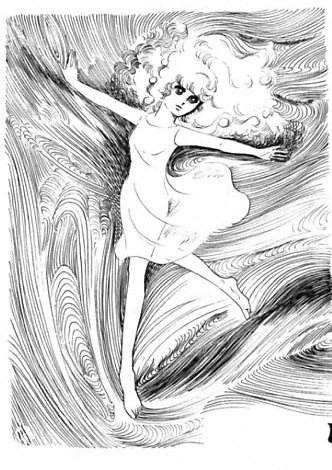

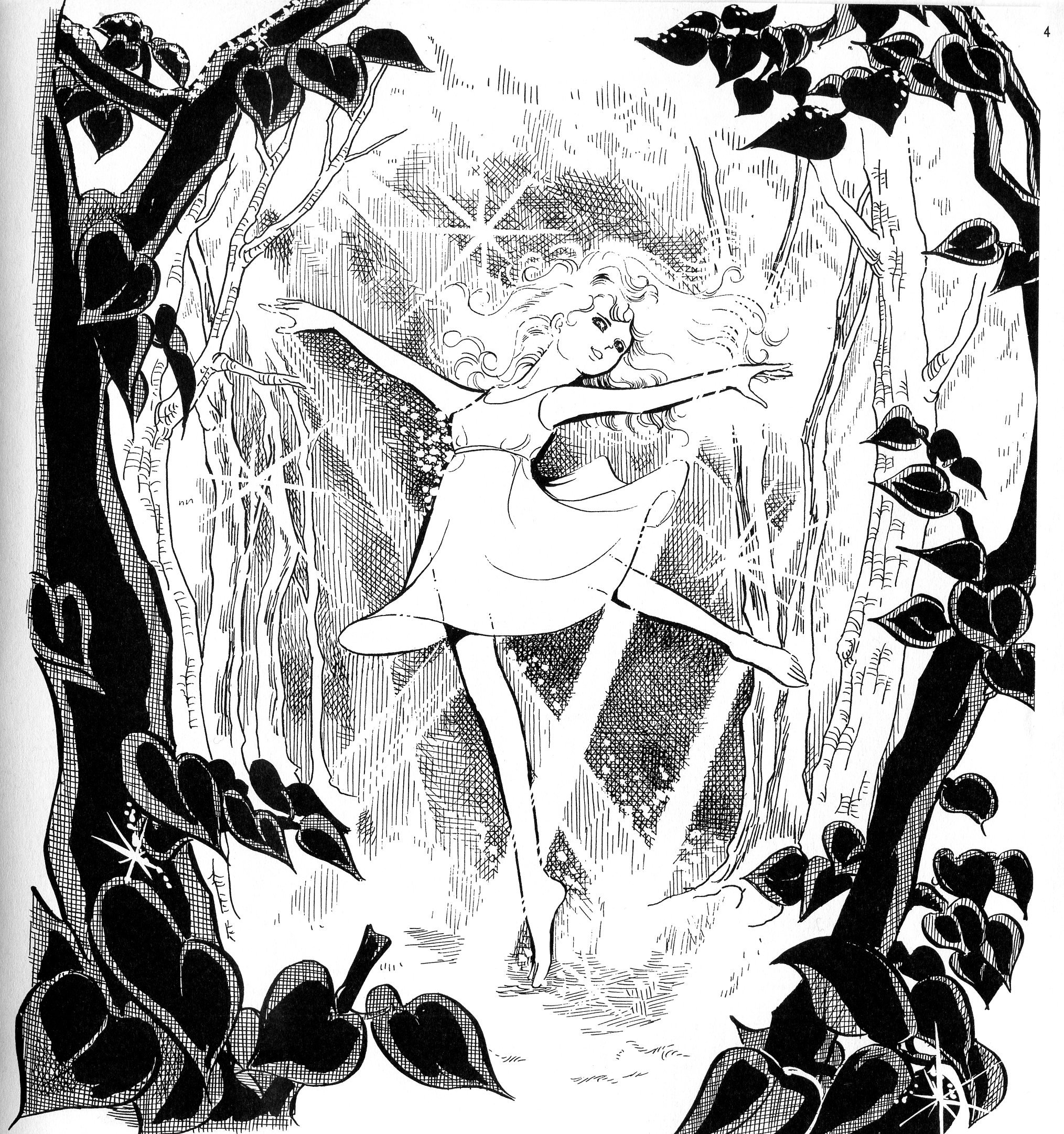

This picture below is by Hagio as herself.

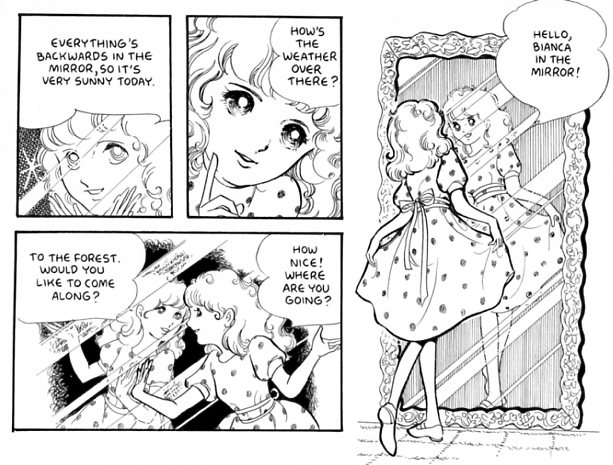

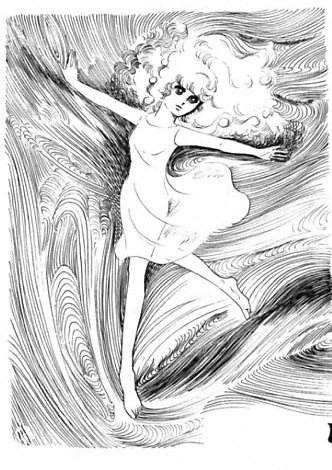

And this is Hagio drawing as Clara.

Contrary to Ken’s suggestion, it’s Clara’s picture, with its swirling backgrounds, stiff pose,and staring eyes, which seems (marginally) more haunted. Hagio’s version of the “real” Bianca is a straightforward confection. I really see no evidence (and Ken, despite his close look at many images, provides none) that Clara’s paintings consistently convey a less nuanced vision of Bianca than Hagio’s drawings do. It’s Hagio, who, as Ken says, “idealizes Bianca, turning her into a cliché: a perfectly posed dancing ballerina”. Both pictures are cloying; Clara’s is maybe marginally less so if you squint at it.

The main takeaway, though, is that Clara draws Bianca just like Hagio draws Bianca. Both idealize the child, and both are, in the logic of the story, right to do so. Again, Clara’s insight and artistry are not an antithesis to Hagio’s; they are (such as they are) one and the same.

3.

Similarly, I think Ken’s focus on binaries causes him trouble here:

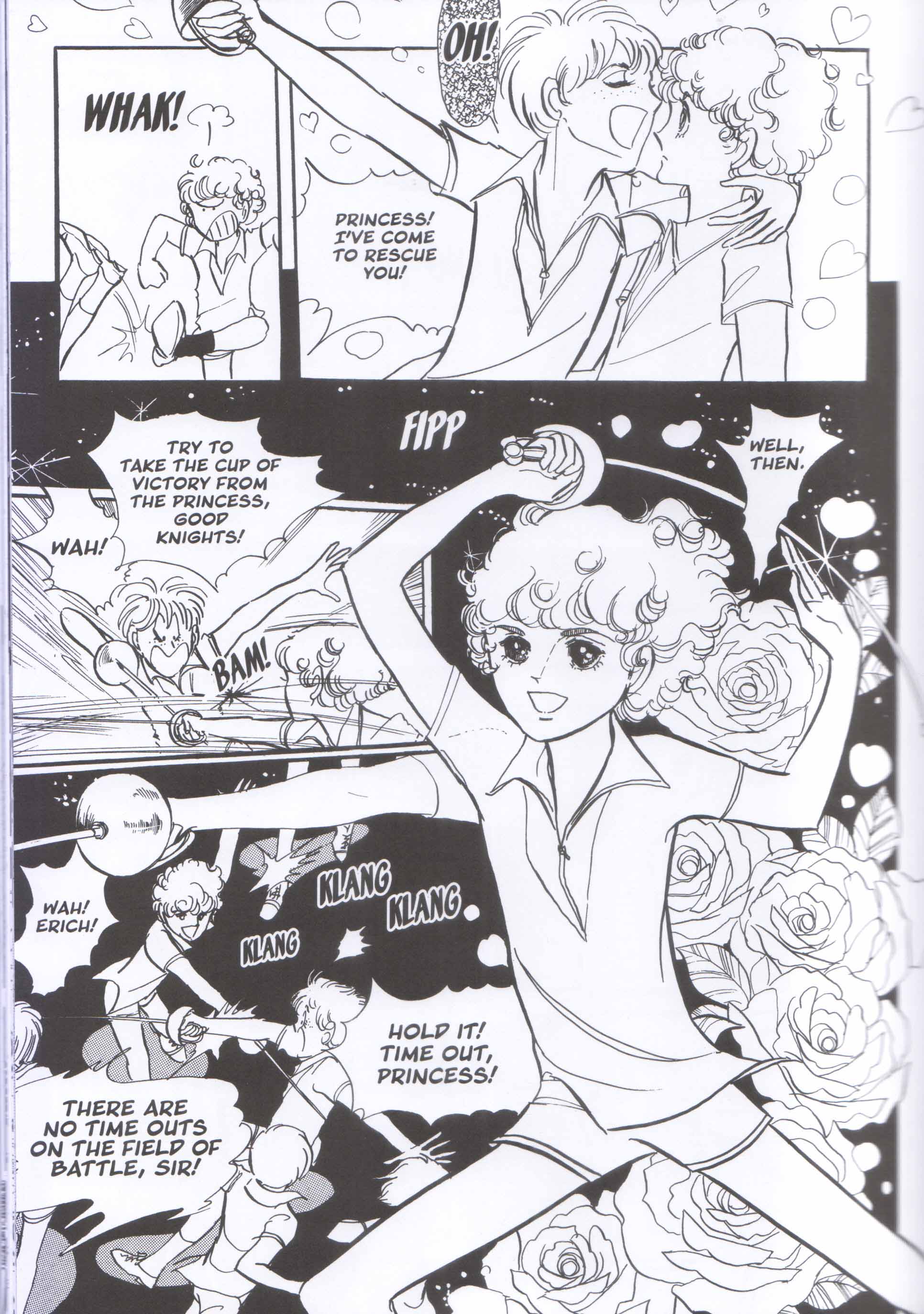

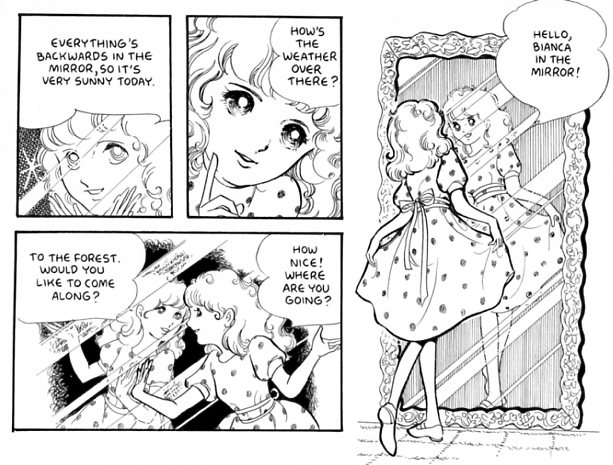

Ken says of this sequence:

When Bianca looks into the mirror, she looks into an adult-free utopia in which the soul always sees its eternal sunshine reflected back at it. To look in the mirror is to look backwards, a nostalgic glance to the soul’s original perfection. The mirror tells us, “The world would be a child’s paradise if only all of those old people would stop screwing it up.”

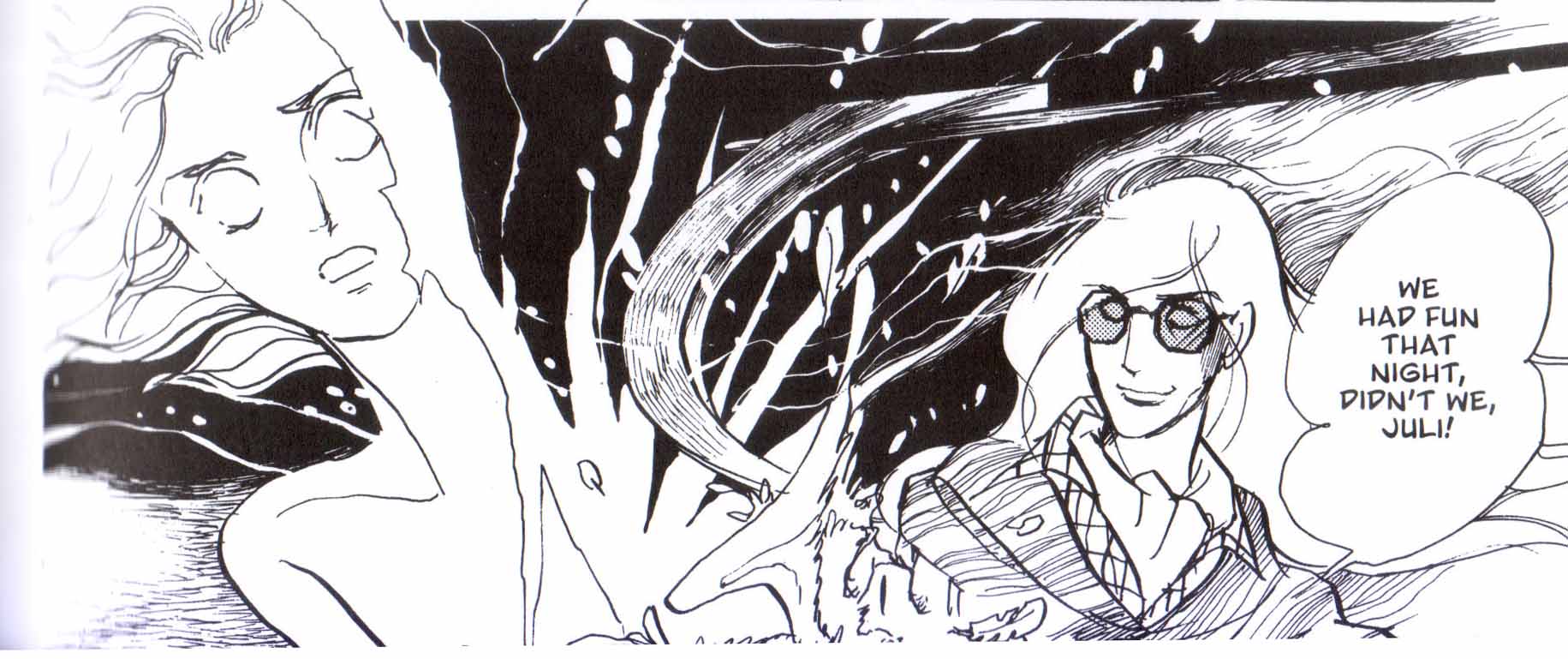

Ken thinks Bianca is delighted by the mirror because there are no adults in it. But (in a panel Ken doesn’t reproduce) Bianca doesn’t say, “Hello no adults in the mirror!” She says, “Hello, Bianca in the mirror!” What’s delightful and exciting about the mirror has to do with Bianca herself. The sunshiny day is obviously a (very, very tired) symbol for a world with no troubles…but the playfulness here, the emotional charge, is in the flirtatious doubling.

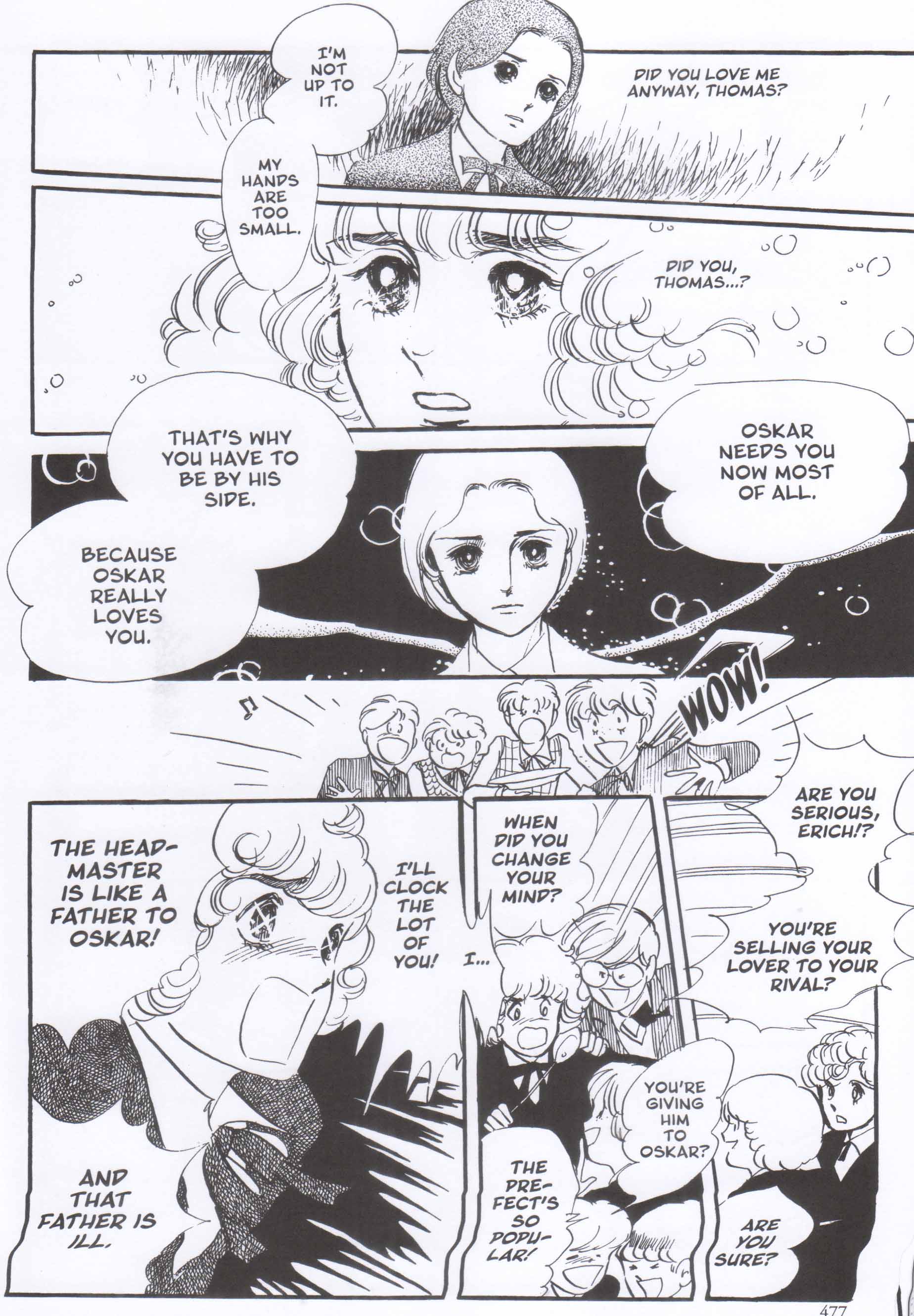

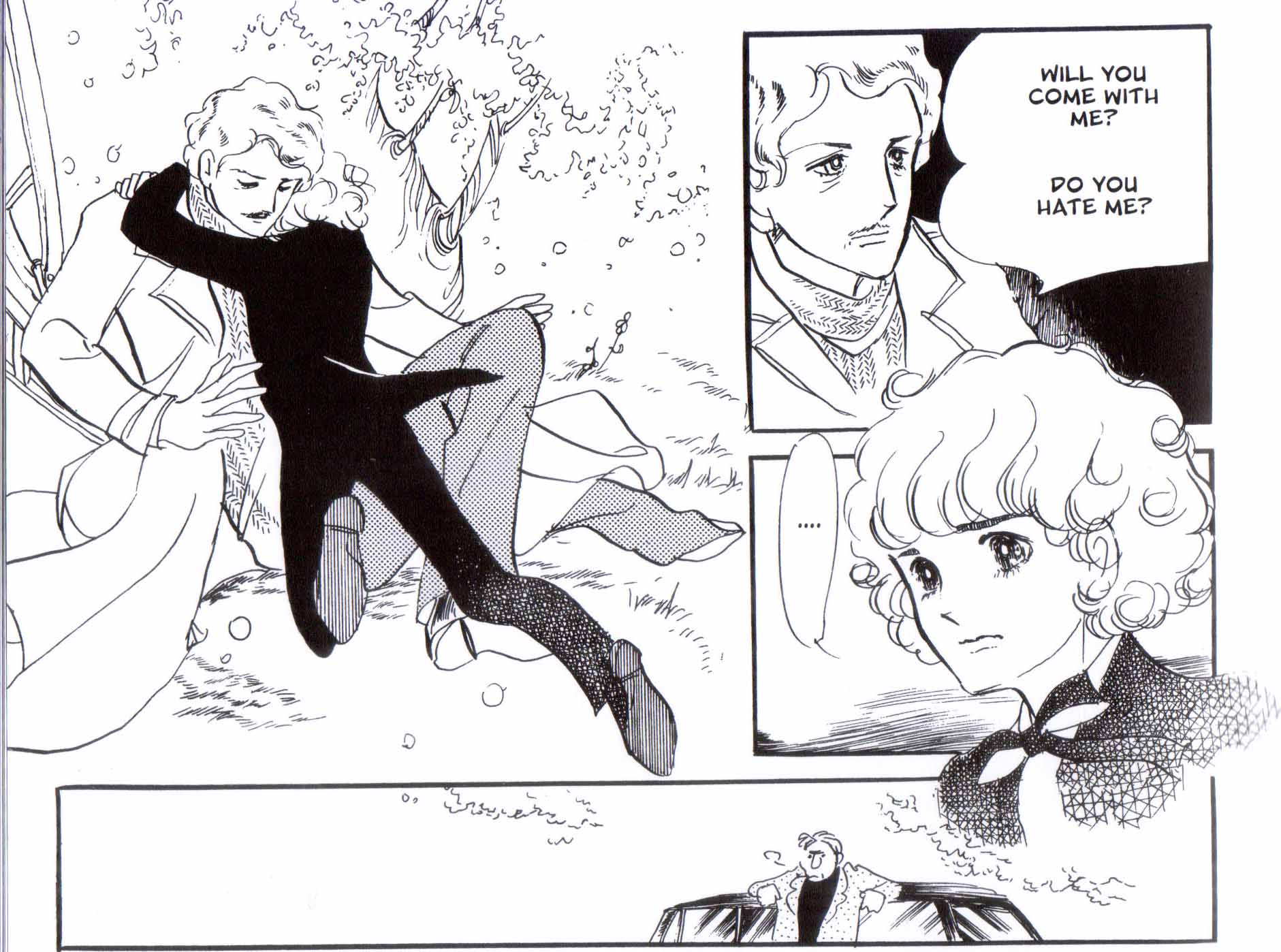

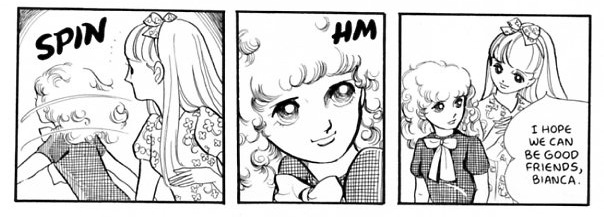

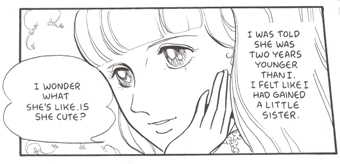

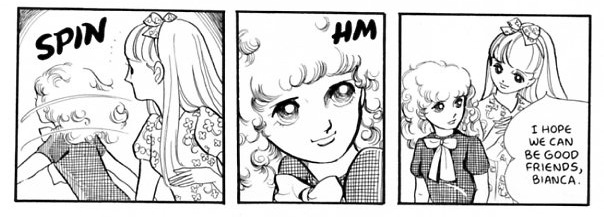

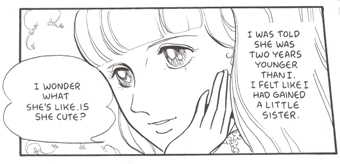

The flirting with the mirror image reproduces the flirtation between Bianca/Clara. From Bianca’s first coquettery:

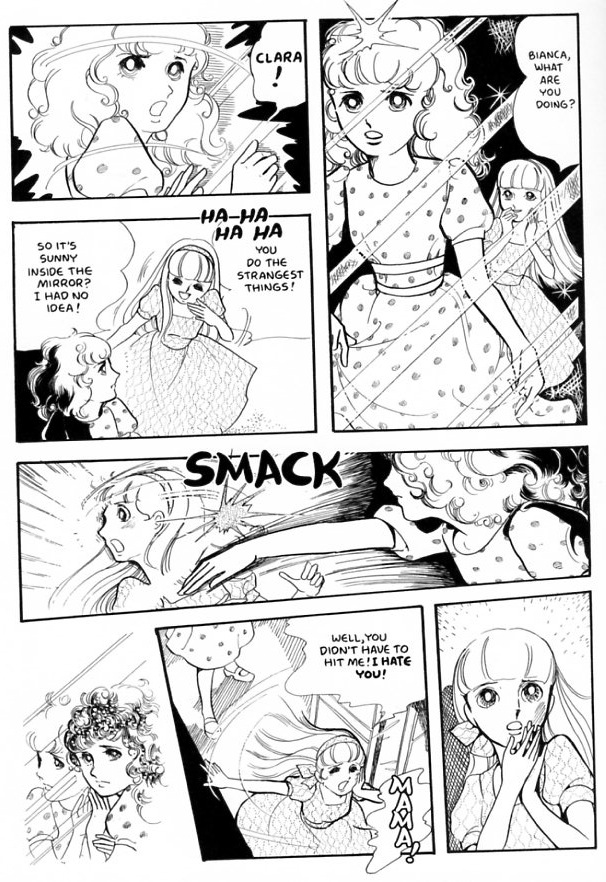

to the lover’s quarrel.

This ambivalent relationship between Clara and Bianca mirrors the relationship between Bianca’s parents, whose break-up diagetically accounts for Bianca’s volatility. Notably, it is Bianca’s mother who has left her father. Similarly, in the sequence above, Bianca rejects Clara — the implication being that both mother and daughter are free spirits escaping domesticity. Thus, it isn’t Clara who is acting like an adult; contra Ken, it’s Bianca.

4.

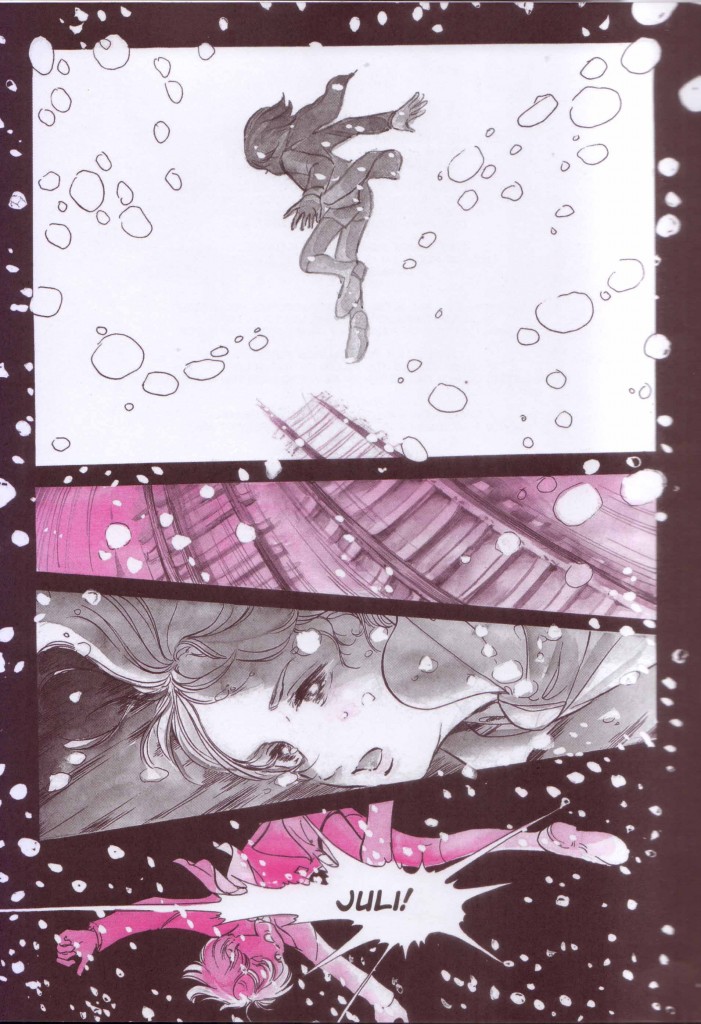

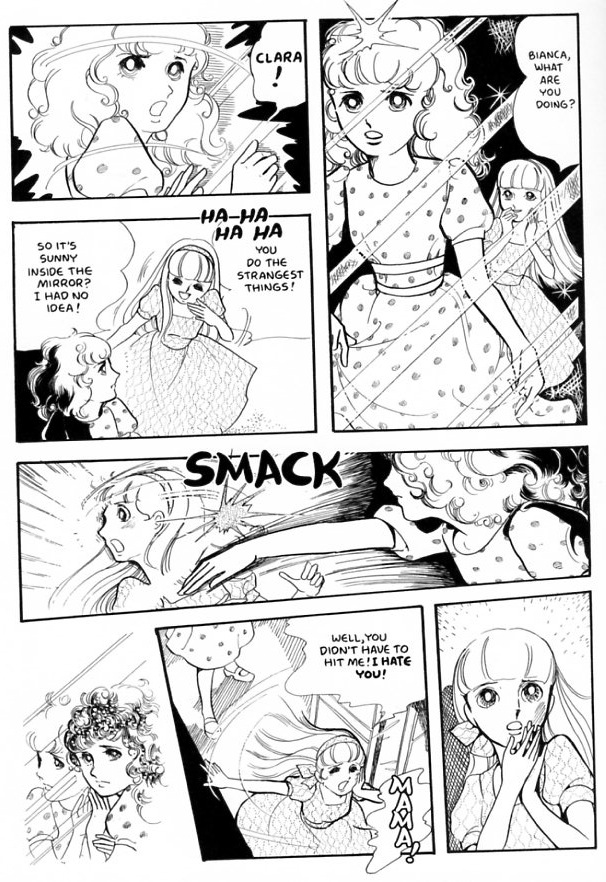

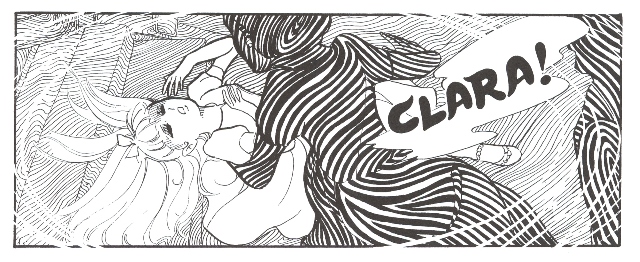

For Ken, the story is about punishing adults. Whether or not that’s the case, there’s not doubt that “Bianca” is more effective at punishing Bianca than it is at punishing Clara. Clara grows up and becomes a successful artist. Bianca suffers death by landscape.

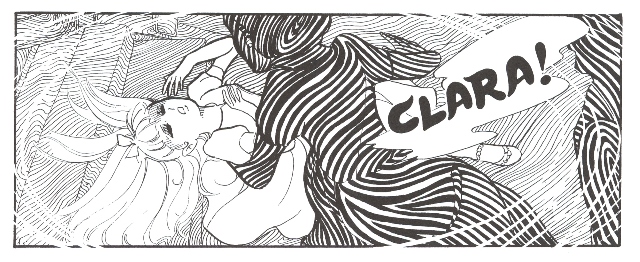

The creator and manipulator of this particular landscape is, of course, Hagio herself. And so it is Hagio who, in an extremely contrived fashion, off the little darling. After which, Clara faints, and her mother swoops in to grab her:

Ken reads this through his familiar binary. It shows adults are bad.

On an interestingly composed page that employs many shading styles, Clara faints after learning of her cousin’s death. Hagio draws Clara’s mother as a series of swirling lines of different weights, and I assume this visual style mimics Clara’s impaired perception: we are “seeing” the mother through the eyes of the fainting girl. Yet these thick black lines give the mother a demonic aspect—and demonic is the deep nature of adults in Bianca’s world, who only appear to be friendly. Coming at a key moment, this visual approach amplifies my reading of the story’s intense antipathy to ageing and adult culture.

But how ominous is this? Clara looks like she’s in raptures. The swirling lines intensify the sense of orgasmic disorientation; it’s one of the loveliest pictures in the story. Moreover, the swirling obscures identity; the mother becomes someone else. Leaning down with her back to the reader, she’s not only a mother, but Hagio herself, protecting — or is that ravishing? — her creation. Bianca drops out of sight and leaves in her wake an ambivalent, melancholy ecstasy.

Clara goes on to spend the rest of her life making an aesthetic fetish of the girl who once rejected her and was then more or less instantly destroyed. For Ken, the fact that this is disturbingly morbid indicates that Hagio is criticizing her character. This rather ignores the fact that Clara and Hagio are doing the exact same thing. Hagio killed Bianca in order to turn her into an aesthetic fetish. Killing children to turn them into aesthetic fetishes is not an especially pleasant thing to witness. And this is why the story is, I’d argue, ugly.

5.

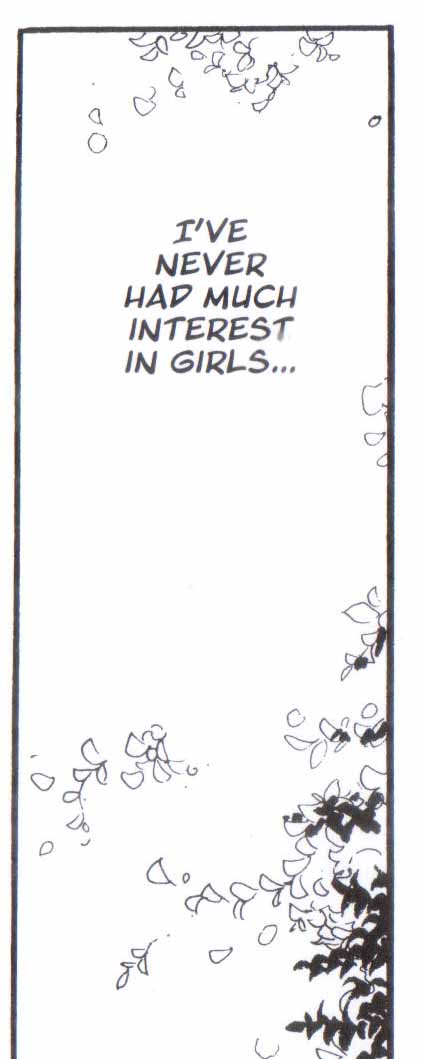

Hagio does not identify as a lesbian. Nonetheless, like almost all of Hagio’s work, Bianca is powered by its queer subtext — emotions unspoken, longings that grow and metastasize like faces in a funhouse mirror. The story desires Bianca, but that desire is not articulated, either by Clara or by Hagio. Bianca is freedom, but what freedom exactly — what emotions, what desires — can’t be named. So Bianca is safely done away with, at which point her image can be retrospectively and safely consumed.

Ken is somewhat stumped as to why Bianca is killed in the forest when (by his binary) civilization should kill her. She should logically die by falling downstairs or some such, if indoor/outdoor is really what matters. But of course that isn’t what matters. The issue isn’t civilization vs. the forest. The issue is getting rid of Bianca in a way that makes her ripe for mythologizing. Having her vanish into her nature —neatly eliding all the issues raised by having an actual, real nature, rather than a picture of one — works perfectly. One with the forest, she embodies freedom, a formulation which conveniently gets rid of her body and of any suggestion as to what in particular she would do with that freedom if she had it.

The point here is emphatically not that Hagio has to tell “Bianca” as a coming out story. But it does seem like there needs to be some acknowledgment that Bianca’s tragedy is not the destruction of her innocence, but the failure to destroy it. After all, Bianca doesn’t grow up. Clara and Hagio prevent her from doing so; they conspire to keep her the perfect, frozen ballerina on a cake so she will never become a friend, a sister, or a lover.

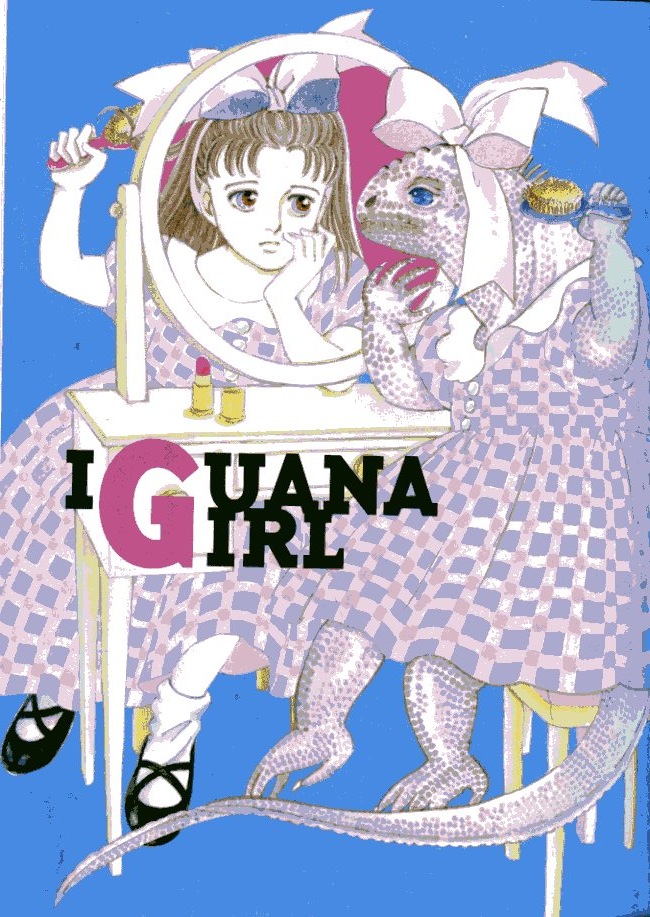

In Hanshin, in Iguana Girl, in Drunken Dream, Hagio is able to make art from an acknowledgement — rather than a refusal — of specific bodies and individual desires. In the story AA’, she confronts the bleak, frozen downside of innocence — of not knowing what you want or who you are —as well as its smiling surface. In all the best work of hers I’ve seen, she explores the queer knot at the heart of identity and love. But “Bianca” is not so courageous. It shakes its finger at the mean repressors for silencing the inner kiddies, while surreptitiously devoting its resources to putting those kiddies quickly and safely underground, so they can be either transformed into treacly images and ignored.

Ken looks at the structure of the forest, but he misses the thing dancing there under the trees. “Bianca” seems trite not because readers haven’t looked at it sufficiently closely. It seems trite because it’s a lie. “Bianca” is a story that celebrates freedom by embalming it. As a result, it’s an emotional and aesthetic failure, hiding what could have been its real concerns with shallow moralism and weak allegories. What’s left is only a shadow of an art that wasn’t; a false picture of a false picture.

____________________

This is part of an ongoing series on Moto Hagio’s Drunken Dream.