Women are beaten time and time again into submission, but they always return, or if one women is eliminated, another takes her place. Whatever it is these women stand for, men and their phallicism are fairly powerless in its presence.”

—Anne Allison, Permitted and Prohibited Desires: Mothers, Comics, and Censorship in Japan

Allison in the above quote is referring specifically to Japanese erotic manga of the 1980s and 90s, but her point certainly fits Junji Ito’s horror manga as well. Indeed, Allison’s quote is basically the plot of every one of Ito’s Tomie stories. In the first of these, “Tomie”, from 1987, the titular heroine, a bewitching high school girl, comes on to her teacher, Mr. Takagi, on a school trip. Another student confronts her, and in the scuffle she falls off a cliff and dies. Takagi then orders all the boys to take off their clothes and cut her body into pieces while the girls look out and make sure no one interferes. The boys then dispose of the pieces of her body. Shortly thereafter, though, Tomie miraculously reappears at school — causing several of her murderers to lose their minds.

This is the prototype for all of the Tomie stories. Tomie, it turns out, is a cancerous monster. Her beauty corrupts men, who love her and then attack her, chopping her into bits. Each piece then regenerates (more or less gruesomely) into a new Tomie. As Allison says, Tomie is always murdered and diced and always returns.

In her book, Allison argues that Japanese families during the 1980s and 1990s were strongly matriarchal. Men worked long hours and traveled even longer hours to work; as a result they were effectively absent from the home. Women were in charge of shepherding children through the complicated and rigorous Japanese school testing regime. The mother-son bond then was supposed to function as a lever to propel children into their place in Japan’s resurgent advanced capitalist society. Rather than an Oedipal dynamic, in which boys symbolically reject the mother to join the world of the father, Allison suggests that in Japan boys see mothers as symbolic of the (still very patriarchal) culture. Resentment against hierarchy and limits often manifests not as competition with men, but rather as resentment against women. Allison argues:

The real stress in all this might be less on teh breakage and more on the display: the show of aggression used as a device to ensure the continuity ofa relationship rather than to sever it…. Such “devices” are found in mother-child relations in Japan, where children are indulged in a degree of aggressiveness (hitting, slapping) against their mothers….

Again, it’s not hard to see how this maps onto Ito’s Tomie stories. Tomie is the constant target of sexual and physical aggression — and of physical aggression as sexual aggression. But all of that aggression is her fault; she is the instigator — the uber-feminine manipulating and devouring men.

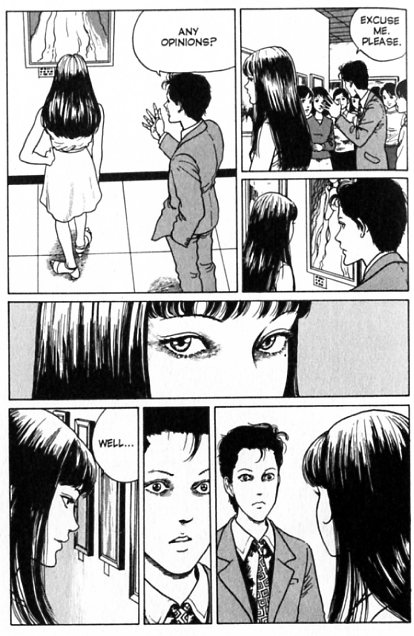

In the ero-manga Allison discusses, men get to dominate women in ways which, while not perhaps entirely convincing (those pesky women keep returning!) are still clearly meant to be provisionally satisfying and empowering. In the Tomie stories, the anxieties are the same, but the outcome is (at least from the standpoint of the male ego) significantly bleaker. In “Painter”, for example, the erotic male gaze — surely a major site of aspirational male empowerment and dominance in ero manga — is brutally and explicitly reversed.

The painter has created a series of portraits of his girlfriend; by gazing at her and commodifying her, he has attained fame, fortune, and dominance. One look from Tomie, though, and that gaze is flipped; suddenly it is not him who has the commodity, but the commodity who has him. At her hypnotic instigation, he jettisons his former model and becomes obsessed with capturing Tomie’s beauty on canvas. He tries and tries and tries, but Tomie — like the education mother, both inspiration and task master — taunts him with his failure. Finally, he succeeds:

What he has captured is, precisely, an image of the commodity — Tomie as bifurcating product — as monstrous excess thing. Woman’s biological reproduction is conflated with capitalism’s artificial reproductive parthenogenesis. The feminine is nightmare proliferation; the object that subjects the gaze.

Reversing the gaze is often seen as a feminist move; a way to turn the patriarchy’s weapons against it. Tomie does certainly enjoy her power over men (at least the bits of her power that don’t involve her being chopped up into bits.) But overall, the feminine/capitalist uber-mommy isn’t exactly envisioned by Ito as empowering for women. When Tomie’s kidney is implanted in another women, for example, the other woman turns inevitably into Tomie. And another girl who encounters Tomie eventually ends up like this.

Women’s power for Ito, then, isn’t something that women themselves control. Rather, it explodes from inside of them, distorting their flesh and sending their severed gobbets across the landscape. Female-as-symbol is constantly bursting out of female-as-body, leaving behind a gaping corpse in the shape of a vagina dentata.

That maw is not so much women as feminized capitalism, a beautiful endlessly proliferating fissure. In one of the stories here, Tomie is a high school’s ethics officer, and that seems oddly apropos. She circulates, a fungible locus of power which reinscribes the same social roles over and over, men and women all welded into an organic, replicating mass by the remorseless workings of pleasure, image, violence and desire.