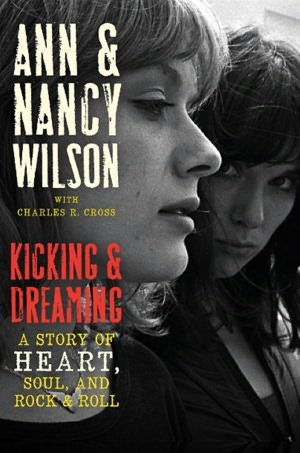

Kicking & Dreaming: A Story of Heart, Soul, and Rock & Roll, Ann Wilson, Nancy Wilson, and Charles R. Cross (It Books, September 2012)

Kicking & Dreaming: A Story of Heart, Soul, and Rock & Roll, Ann Wilson, Nancy Wilson, and Charles R. Cross (It Books, September 2012)

As I work my way through the biographies of all my seventies and eighties rock heroes, I realize there’s no point in fighting my demographic destiny. I did expect this book to be dreadful, at least. Dreadful and tedious. Dreadful and tedious and full of repetitive boredom. Dreadful and tedious and full of repetitive boredom and clichés. And of course it is not entirely free of dreadful, tedious, repetitive, boring clichés, but mostly it is “surprisingly readable,” title aside.

I have always wondered how Ann and Nancy Wilson managed to become kick-ass stadium rock stars in the age of Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones and Aerosmith and all those other very, very male bands. I always wanted to know how much of the early guitar sound was Nancy and how much of it was Roger Fisher. And I always wanted to know how eighties and nineties Ann felt about being piled with huge hair and big, dark costumes, and shot mostly from the chin up in their videos in a viciously stupid attempt to keep us from noticing she had gained weight. (Answers: because they kicked ass; more Roger, in the songs I like best, but the acoustic stuff is Nancy; and humiliated and irritated, as one might expect.)

The book is told in snippets of narrative by Ann, by Nancy, by other members of Heart, by associates, friends, their mom, and Chris Cornell. This is a half-assed way to put a book together, but it does give Ann and Nancy their own voices. And they are charming. As fluttery, breathlessly dancing in a sun-dappled springtime meadow as you’d expect of anyone who wrote “Dreamboat Annie” and “Dog and Butterfly” and so on, but also as driving and relentless as you’d expect of someone who wrote “Crazy on You” and “Barracuda.”

That’s the dichotomy that made Heart brilliant, and frustrating. I can’t listen to any of their albums all the way through, and individual songs are often divided against themselves, the wild, hard-driving fervor never blending seamlessly with the frothy, acoustic effervescence. (I should point out that I speak of Dreamboat Annie through Bebe Le Strange; I don’t entirely acknowledge the existence of any of their other works.) But they have written some of my all-time favorite songs. I wonder if the hit and miss situation with so many Heart songs is because they were feeling out something that nobody had done yet.

A couple of million critics have written about this dichotomy as a balance of masculine and feminine, but that misses the point. It’s all feminine, and what gets called masculine is instead a side of femininity we don’t usually acknowledge. It was thrilling, back in the seventies, and it still is, more than thirty years later, even though we’ve gotten used to seeing women on a stadium stage. (“Straight On,” for instance, or “Magic Man” – these are pretty much perfect rock songs.) Which brings me back to wondering how they did it, when they did it. Or any time – but especially in the mid-seventies.

And they explain pretty well, considering that it’s really just one of those things. They start out by meticulously recounting their early lives, and in fact their entire family history. I found this touching, in part because I’m a huge fan of putting things in chronological order, but also because they love their family, and each other. I’m into that. They were a military family and moved all over the world during the girls’ childhood, making Ann and Nancy a solid, close unit. They were also musical from a young age. And they found the Beatles. Ann and Nancy see that as the crucial pinch of magic dust that launched them – or Ann, specifically – toward stardom. I’m less convinced; while all their friends were playing at being Beatle girlfriends, Ann and Nancy were pretending to be the Beatles, with guitars and everything. They already had whatever it was.

Next up: Who wrote what. I want to know who slept with whom or what as much as the next person, but I also want to know who wrote what, and under what circumstances. And the book has a lot about the music and about dealing with the music industry, which is always fascinating, in a degrading, evil kind of way. I’m curious about what inspired the songs, too, but that’s usually sort of discouraging. Magic Man, for instance, was a straight-up homage to Ann’s first and overwhelming love, Michael Fisher (brother of guitarist Roger Fisher and, for a few years, their manager). I’m somewhat uncomfortable with that overboard, overwrought song being about a specific man. That’s what happens when you listen in on someone’s creative process, though.

The book is also very much about Ann’s struggle with her weight – or, more accurately, the music industry’s struggle with Ann’s weight. She started gaining in the eighties and, eventually, she was fat. It doesn’t seem like such a horrible thing, but it just wasn’t allowed, in society or, especially, in the music industry. The shit everyone gave her over it destroyed her self-confidence, that blistering individualism that allowed her to get on the stage in the first place. (Well, that, and the music industry in general, and coke.) Have you seen any of those videos from the eighties and nineties? They have Ann’s hair so big she can barely stand beneath it, and her jackets and dark and broad of shoulder, excessive of lapel. She is shown in shadow, cloaked in smoke, or only in close-up, where the big hair and startling blush situation are supposed to fool the eye into thinking she’s smaller than she is. Or, perhaps, just short circuit the viewer’s thought process from an overload of confusion and perplexity. Either way, it’s pathetic. This is a beautiful and shockingly talented woman, and all the music industry could think to do with her was turn her into some kind of clown. That, and focus on Nancy.

This was more or less their approach to the music, as well. Most of Heart’s hits came after Bebe LeStrange, the 1980 album I consider their last acceptable one (although I haven’t checked in recently – I guess their albums from the last two years, Red Velvet Car and Fanatic, could be great – but I wouldn’t bet on it). Ann and Nancy tell the story of how the music industry repackaged them in the eighties, choosing hits they didn’t like and clothes they found ridiculous. I was pleased to find this out, because some of that shit is very, very bad, and knowing they realize this, at least to some extent, makes me feel much better about things. All the dirt about the music industry and its hangers on, by the way, is good stuff. It becomes very clear how bands go from brilliant to embarrassing in the space of one album. (Hint: Letting the music industry tell them what they need to do if they want to make it really big. Also, coke.)

I’d read a couple of popular feminist books recently, and I was surprised to find that the Heart biography was one, too. I don’t know why it surprised me, given their beginnings – perhaps because of songs like “All I Want to Do Is Make Love to You” (which it turns out Ann never liked, thank god; that song is the kind of shit you can’t wait to wipe off your shoe, and even then, you keep smelling it anyway). Ann feels strongly that she was judged by different standards than male rockers were judged by, and she suffered for it, and she resents the hell out of it. That isn’t tricky, as feminist arguments go, but sometimes simple is good. (I was glancing through the Amazon reviews, by the way, and noticed that Ron, an Indiana Republican who can’t spell, is unhappy about the book’s liberal leanings. Life must be frustrating for Ron.)

I got involved with this book, and not just because I spent at least a week reading it (its not exactly tight, and when you’re reading it in spurts of fifteen or twenty minutes a day, it seems endless). Also, I feel that now the Wilsons and I are so close, it’s cold of them to obviously leave out so much of the dirt – because the absence of certain things is palpable. (For instance, despite a decent number of generalized statements about drug use, there are surprisingly few actual anecdotes, making me suspicious. And in the later years, we learn about Nancy’s marriage to Cameron Crowe — and the demise thereof — but there’s almost nothing about what Ann was doing in her personal life over the last twenty years. What up, Ann?) So, it was a bit of a slog, and a vague slog, at times, but that was all right. Ann and Nancy are likeable, and interesting, and they kick ass.

And I just saw that Rod Stewart has a biography out. God damn it.