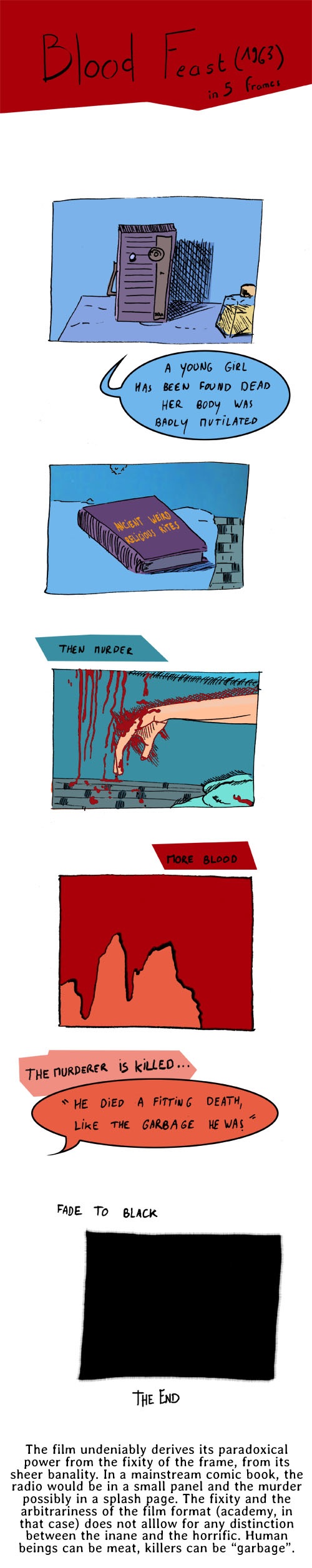

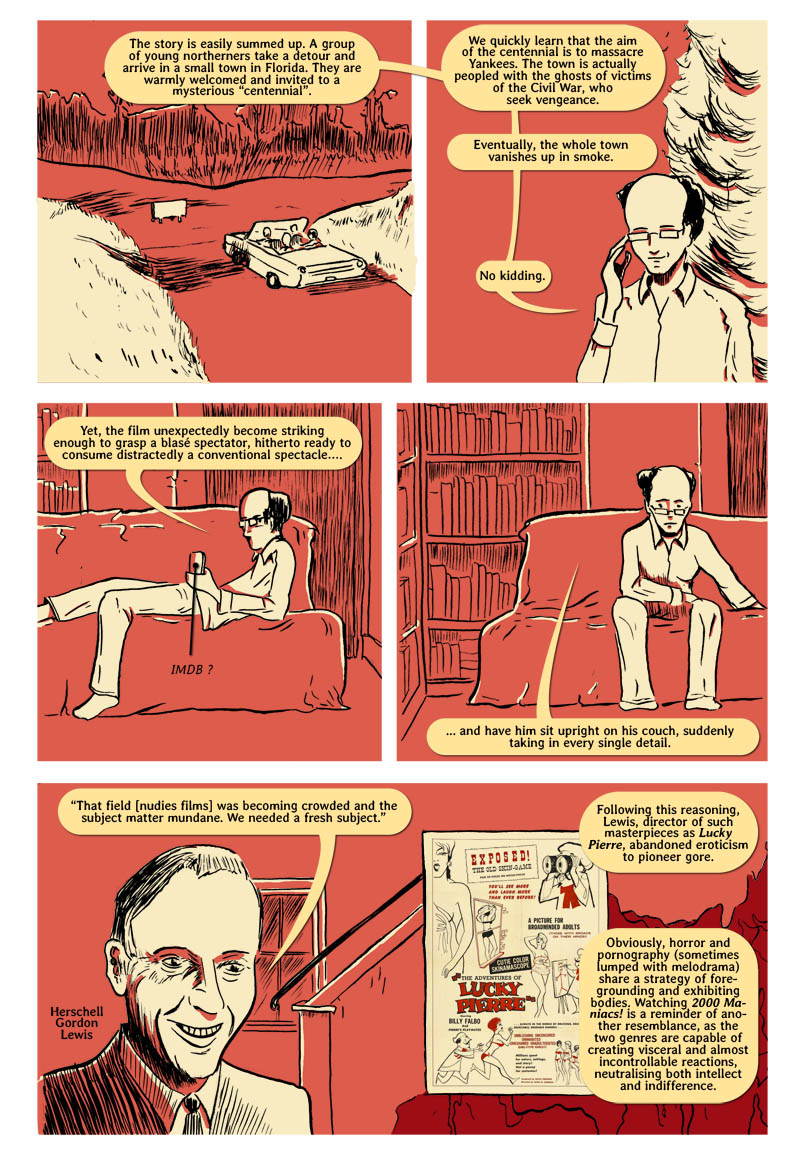

In 1999, Warren Ellis, John Cassaday and Laura DePuy explored the Godzilla imagery in the second issue of Planetary, “Island”. The series was still in the process of codifying its relationship to its readers and was very open about its objectives and methods. It sought to present the archeology of fiction by conflating the narratives of popular texts and their very existence as popular objects, and having the heroes of the series excavate and interpret these condensed remains.

The carcass of Mothra, in Planetary #2 (May 1999)

Thus, when the Planetary team meets Godzilla, they also encounter Godzilla, the cultural phenomenon. The history of the monster merges with the history of the monster genre and the demise of the latter mean the former have turned into rotting carcasses. In the series, these rotting carcasses are to be found on Island Zero, where the Planetary team is summoned in order to stop a sect, whose members intend to feast on the corpses of the Kaijus. By the time the team arrives, the members of the sect and the local Japanese soldiers have killed each others, positioning the heroes as spectators. Only at the end of the issue does the reader get a modicum of explanation, through a piece of expository dialogue:

Jakita Wagner: It all started the day after Hiroshima. […] We can’t say it was an atomic bomb. We can’t say these things are radioactive mutants. I mean, that’d be stupid. […] But five years later, island zero was populated by great monsters. They died off for some reason. They never left the island and they died.

The parallels are obvious, and even readers with a passing knowledge of the daikaiju genre are likely to notice the similarities between its history and Jakita’s story: the Japanese giant monsters movies appeared after World War 2, with Godzilla in 1954, and the giant pterodactyle Rodan (a stunning sight in the last page of the Planetary issue) in 1956, then spawned a popular series of films until the mid-70s before a prolonged eclipse; although the genre was very popular in Japan, it also remained profoundly insular, exotic imports in the rest of the world, it “never left the island”. The “five years later” reference does not quite match, though it could be a reference to 1948 Unknown Island, a little known RKO film by Jake Bernhard, in which a group of adventurers stumble a lots island populated by (giant) dinosaurs, in the form of cheap costume-wearing extras.

Unknown Island (1948) trailer

Planetary thus transmuted the history of the genre – a history shaped by Western perception, which means the 80s renaissance of Godzilla, which was barely distributed abroad, can be ignored – into a history of the dead monsters on Island Zero. This strategy, which the series applied to a variety of popular genres and cultural objets, has been since praised by critics and academics as a challenging, complex and satisfying bridge between meta-fiction and popular texts.

I suspect that in the last few years, this conflation of Godzilla and Godzilla has become the default mode of engagement with the character. This is at last what the two most recent film incarnations of the King of the monsters suggest. Indeed the most interesting sequences of both Godzilla Final Wars (Ryuhei Kitamura, 2004) – the final Japanese entry in the franchise – and Godzilla (Gareth Edwards, 2014) both introduce the history of the franchise in the diegetic world. In both cases, this insertion occurs during the opening credits, setting the tone for the whole film.

During the credits of Godzilla Final Wars, excerpts from previous films in the franchise are intertwined with rolling dates, from 1954 to the present. The status of these images is not made explicit, but the construction of the sequence connects the chosen excerpts to suggest a continuous narrative rather than a collage. The movies blend into each others, are presented out of chronology, accompanied by prominent dates (1960, etc.) which do not correspond to any film, and create an artificial continuity. Godzilla is thus presented as having been a continuous presence since 1954, a description which can only be applied to the cultural phenomenon it represents, and is incompatible with the premise of most of the movies compiled in these sequences. Godzilla’s death at the end of the first movie, but also the various reboots, are glossed over, the better to repurpose existing images. Plots, foes and stories are briefly cast aside in order to foreground the cultural icon trough its five decades of existence, archetypally stomping over cities and soldiers. Though the movie itself includes numerous homages – and even a match versus the 1998 Emmerich version – it never develops this idea explicitly.

In Gareth Edwards’s Godzilla, the process is slightly less overt. As in the case of Godzilla Final Wars, the credit sequence opens with images of an atomic blast footage, before inserting Godzilla into actual footage from the 1950’s atomic tests in the Bikini islands. 1954 is only mentioned later in the film, in a passage of blunt exposition. Nevertheless, popular-cultured spectators are expected to understand that the discovery of the creature roughly coincides with the date of Honda’s first film.

True, this is a revisionist reading of the origin of the creature and of the American role in particular. In Edwards’s films, based on a script by Max Borenstein the tests did not disturb Godzilla, they were an attempt to destroy the creature. However, this history again acknowledges the age of the franchise, its historical origin. Incidentally, this is also, as in the case of Planetary, an example of redacted, or secret history. We are invited to re-read what we thought we knew: we thought we were familiar with the Bikini tests, we thought we knew Godzilla, but a new light will be shed on both.

Godzilla (2014), opening credits

Although both films purport to be modern takes on the king of monsters, it is striking that they both emphasize the age of the franchise and its now removed point of origin. In doing so, they acknowledge the fact that the Godzilla franchise – a familiar series of cultural objects, with a well-established connection to the atomic trauma in Japan – is bigger than any specific movie. The success of both endeavors is predicated on the existence of an audience eager to connect with the franchise as a whole rather than with a specific film or series of films. The story of the Japanese Godzilla may have been rebooted in 2000, but it is hard to conceive of a spectator going to see Final Wars with no awareness of the previous films. Neither film is a period piece, though: Godzilla is at once current and historically grounded, as if some of Planetary’s erudition and esteem for its readership has seeped into both productions. Still, while Planetary made the exploration of the link between history and stories the center of its narrative, the movies contain it in a space where they can still claim plausible deniability. The ambiguous space of the opening credit seems perfectly appropriate to negotiate this tension.

The comparison with the 1998 Roland Emmerich version is enlightening. That film tried to imagine a modernized origin, one which would transpose the story of the original films with no respect for the film as film. It is hard not to see this as another expression of the changing conception of the audience among mass media producers. The subculture connoisseur may not be the target audience, but he or she is important enough to warrant the creation of these two opening sequences.

More generally, this embrace of history also sheds a light on the cultural status of various icons of popular culture. Godzilla is a 1954 creation and the movies acknowledge it, yet it seems unimaginable to have a major Superman or Batman film taking the thirties as a point of origin (Captain America is a somewhat complex exception here, since the character is both of the forties and the sixties). DC did produce a short film doing for Superman what the opening credit of Godzilla Final Wars tried to achieve, but crucially, it was distributed separately from Man of Steel, thus maintaining a clear distinction between the character in the story and the character in cultural history.

Superman at 75

It may be that Superman and the other superheroes have a less overt relation to their historical points of origin. It may also be that these characters haven’t been consistently used a mass-media franchise over the course of their existence – Superman Returns did touch on the tension between diegetic and non-diegetic time. It may be the fact that explaining a 50+ year-old Godzilla is more acceptable than a 70+ year-old Batman. Or it may be that a franchise with a history is less likely to be repurposed as entirely in a different setting as super-heroes have been over the last 16 years.