This piece first ran at Slate.

_____

Even by the wretched standards of the entertainment industry, superhero comics are known for their dreadful labor practices. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the creators of Superman, famously sold the rights to the character to DC Comics for $130, and spent the latter part of their lives, and virtually all their money, fighting unsuccessfully to regain control of him. Similarly, Jack Kirby, the artist who co-created almost the entire roster of Marvel characters, was systematically stiffed by the company whose fortunes he made. Though most of the heroes in the Avengers film were Kirby creations, for example, his estate won’t receive a dime of the film’s $1 billion (and counting) in box office earnings.

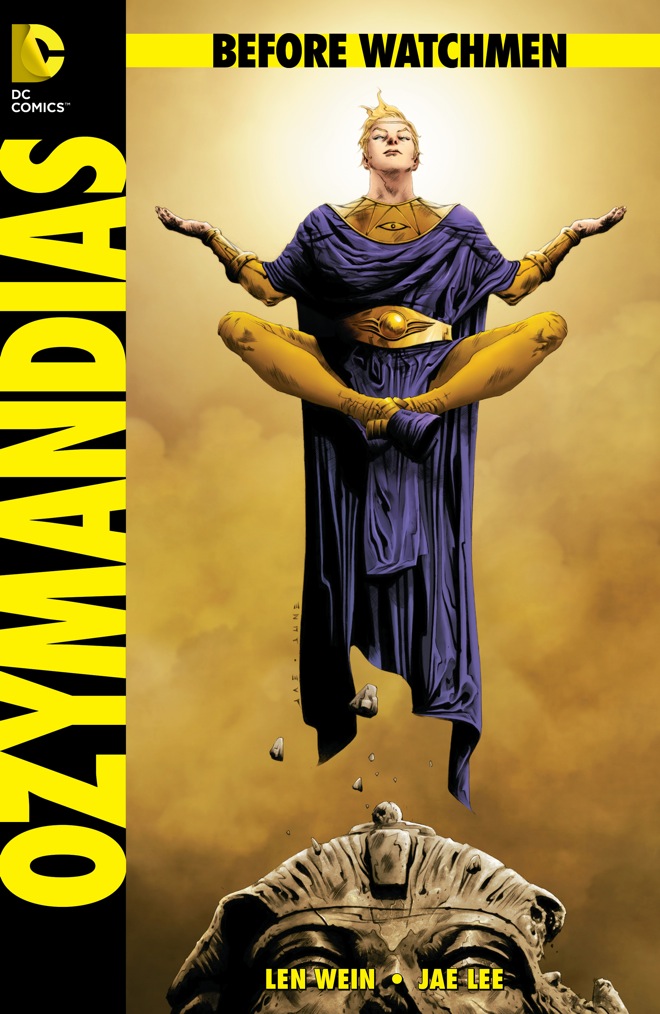

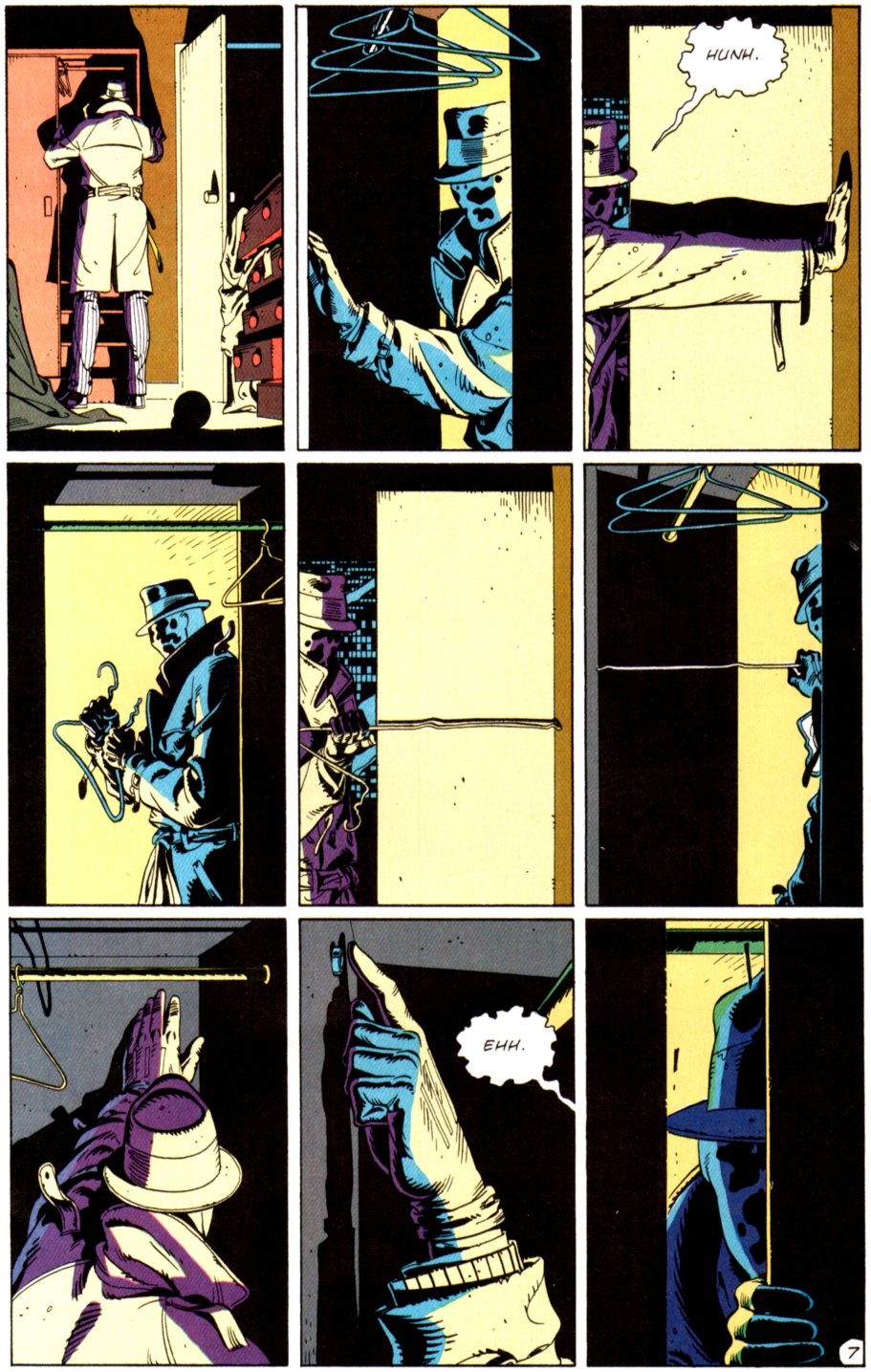

In keeping with this depressing tradition, DC will, next week, begin releasing new comics based on Watchmen, Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s seminal 1986-87 series. Before Watchmen will include not one, not two, but seven new limited series, written and drawn by some of DC’s most popular creators, including Brian Azzarello, Darwyn Cooke, Amanda Conner, and Joe Kubert. Watchmen demonstrated to a mainstream audience that comics could be art, and became one of the most popular and critically acclaimed comics of the last 25 years. Up to now, it had also been one of the most sacrosanct. For over two decades, DC has resisted the urge to publish new material featuring Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, or the Comedian.

You’ll notice the list of writers and artists involved with Before Watchmen includes neither Moore nor Gibbons. This is not unusual in superhero comics. Most work for DC and Marvel is created on a work-for-hire basis. Thus, the original creator of, say, Walrus Man will usually go into a deal with one of the big two comics publishers knowing that the Titan of Tusk will become the company’s property—his aquatic adventures to be written and drawn by whomever the corporate overlords deem fit.

What is unusual, though, is the vehemence with which the original creator has denounced Before Watchmen. It’s true that back in the ’80s, DC tried to get Moore and Gibbons on board for a sequel. That didn’t pan out, though, and in the ensuing decades, Moore’s relationship with DC has soured, to put it mildly. Among (many) other things, Moore became increasingly angry with the company over the handling of the rights to Watchmen itself. In the original contract, DC had written a provision stating that the comic and the characters would revert to Moore and Gibbons once the series went out of print. Moore had assumed that, as with all comics in those pre-“graphic novel” days, this would happen within a few years. Instead, of course, Watchmen was a massive hit—so massive that the trade paperback collection of Watchmen has been in constant publication, and probably always will be.

Gibbons has largely seemed content with DC’s perpetual ownership of Watchmen. Moore, though, is a different story. He refused to accept recompense for the 2009 Watchmen film, which he referred to (sight unseen) as “more regurgitated worms.” As for Before Watchmen, he made his position painfully clear in an interview: “I don’t want money. What I want is for this not to happen.”

Watchmen‘s canonical status, combined with Moore’s dissent, has led to an unusually vocal backlash against DC. Chris Roberson, a sometime DC writer, decided to stop accepting work from the company because of its record on creator’s rights. Cartoonist Roger Langridge, who wrote the acclaimed series Thor: The Mighty Avenger for Marvel, followed suit, explaining that “Marvel and DC are turning out to be quite problematic from an ethical point of view to continue working with.” And Bergen Street Comics in Brooklyn will not be carrying the Before Watchmen titles; in explanation, Bergen Street’s manager, the comics critic Tucker Stone, said, “This is just gross, and we don’t want to be part of this one.”

It would be nice to say that Roberson, Langridge, and Stone are at the forefront of an all-out revolt against DC and Marvel’s business practices. That’s not really the case, though. For the most part, DC and Marvel’s writers and artists are still writing and arting as they always have; comics stores are still carrying the comics; and fans are still buying. Yes, if you go stumbling about in the comments of mainstream comics blogs (here for instance), you’ll find some outrage on Moore’s behalf. But you’ll also find a significant number of folks who don’t care, and who are actively irritated that anyone thinks that maybe they should care: As one fan said, “Alan Moore is a very arrogant guy that really hasn’t done anything relevant in a very long time and should really spend more time creating and less being a cranky old guy in a pub.”

J. Michael Straczynski, one of the writers on Before Watchmen, summed things up for many when he asked rhetorically, “Did Alan Moore get screwed on his contract? Of course. Lots of people get screwed, but we still have Spider-Man and lots of other heroes.”

Straczynski’s contrast between Alan Moore (screwed!) and Spider-Man (still ours!) nicely sums up the fandom dynamics of superhero comics. Creators are there to churn out marketable, exploitable properties … and then disappear. And because the comics companies own the characters, and because they have substantial marketing departments, they’re in a position to make that disappearance stick. Who knows who created all those different Avengers? Who knows who created Wonder Woman? Who cares? We want our modern myths packaged and available at our corner store and on our movie screens. Also … toasters.

Why is Moore complaining? It’s not about the money, as he’s said. (That’s probably a big part of the reason people call him a crank.) But Moore created a group of characters and the world they live in; those characters still mean something to him. Now a company he believes has screwed him over gets to colonize and even define that world. For example: Moore’s comics have often been concerned with feminism, and one theme of Watchmen is that the superhero genre is built in part on retrograde sexual politics and thuggish rape fantasies.

And how does Before Watchmen address these issues? Like so.

If this were some piece of fan fiction detritus—naked Dr. Manhattan, porn-faced Silk Spectre!—it would be funny. But given that this is an “official” product, it starts to be harder to laugh it off.

Of course, this is one of the things that always happens with art. If you create a beloved character or story, others are going to honor it, parody it, use it, and abuse it. That’s why there’s fan fiction. Indeed, Moore and artist Melinda Gebbie literally defiled Dorothy Gale, Alice (of Wonderland), and Wendy Darling in their exuberantly pornographic Lost Girls. Given that, what does Moore have to complain about exactly?

What he has to complain about is that he doesn’t own his own characters … and the company that does own them is free to pursue any version of the characters it likes, whether honoring Moore’s original vision (as DC has been careful to assert) or turning it into bland, infinitely reproducible genre product (as many suspect they will). And DC has the marketing might to ensure that, in the end, its version will be the one that’s remembered. After the third or fourth Before Watchmen movie, which iteration of the characters will be most familiar to the public? Rorschach and Nite Owl and Dr. Manhattan have been raised from their resting place, and Moore—and the rest of us—now get to watch them stagger around, dripping bits of themselves across the decades, until everyone has utterly forgotten that they ever had souls.