This first ran on Splice Today.

______

Comics in the United States have traditionally been associated with guys. The stereotype of superheroes as male adolescent power fantasies has more than a little truth to it; Neil Shyminsky’s informal survey found that 95% of X-Men readers were male. Surveys focusing on a wider array of comics have found a less lopsided breakdown, though one still tilted towards men.

But the link between comics and XY chromosomes isn’t some sort of preordained biological truth. In fact, in Japan, comics (or manga) have been read by just about all demographics — kids, adults, men, women, and everybody else. Manga’s deliberate appeal to a wide range of audiences is one reason it became so successful in the U.S. in the 90s: shojo manga titles, or comics for girls, catered to a niche in the American market that the mainstream superhero publishers were unable/unwilling/too clueless/too sexist to fill.

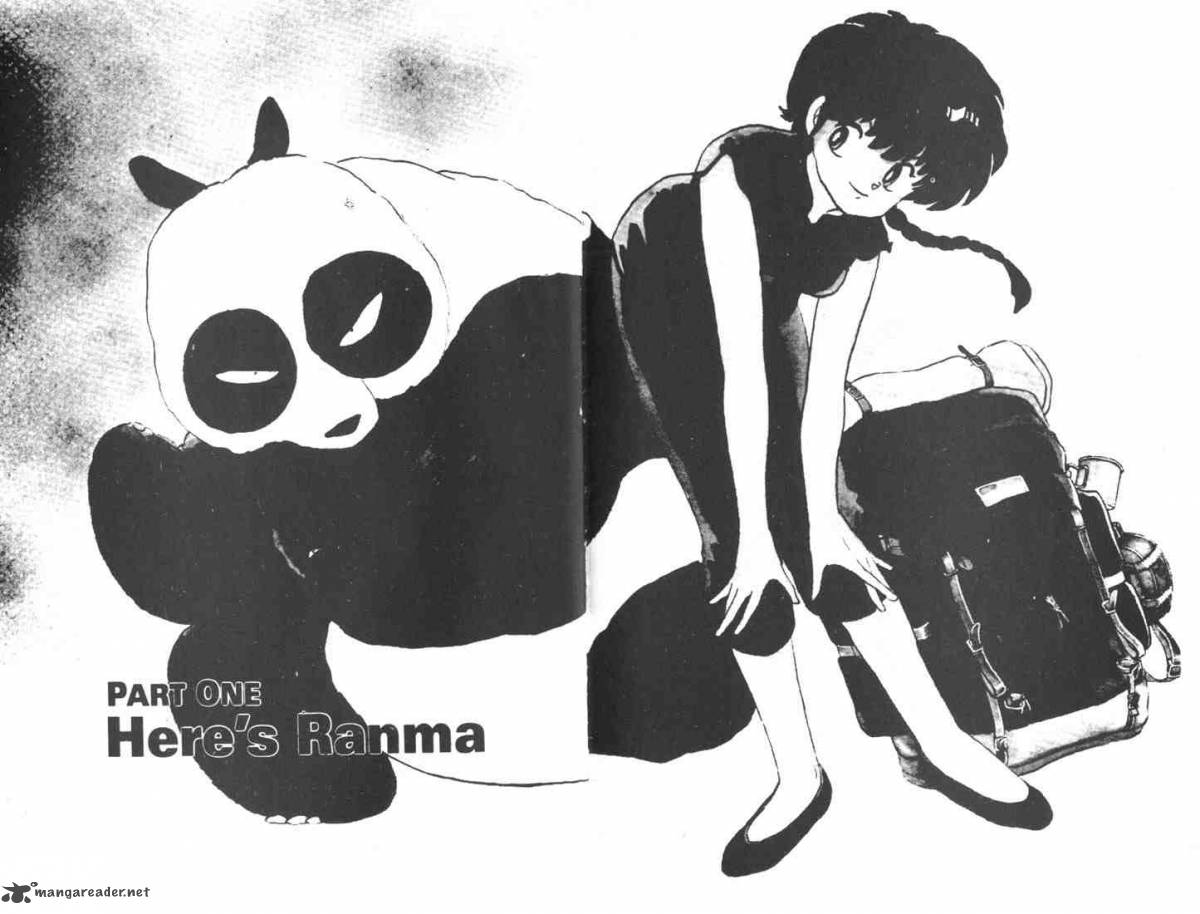

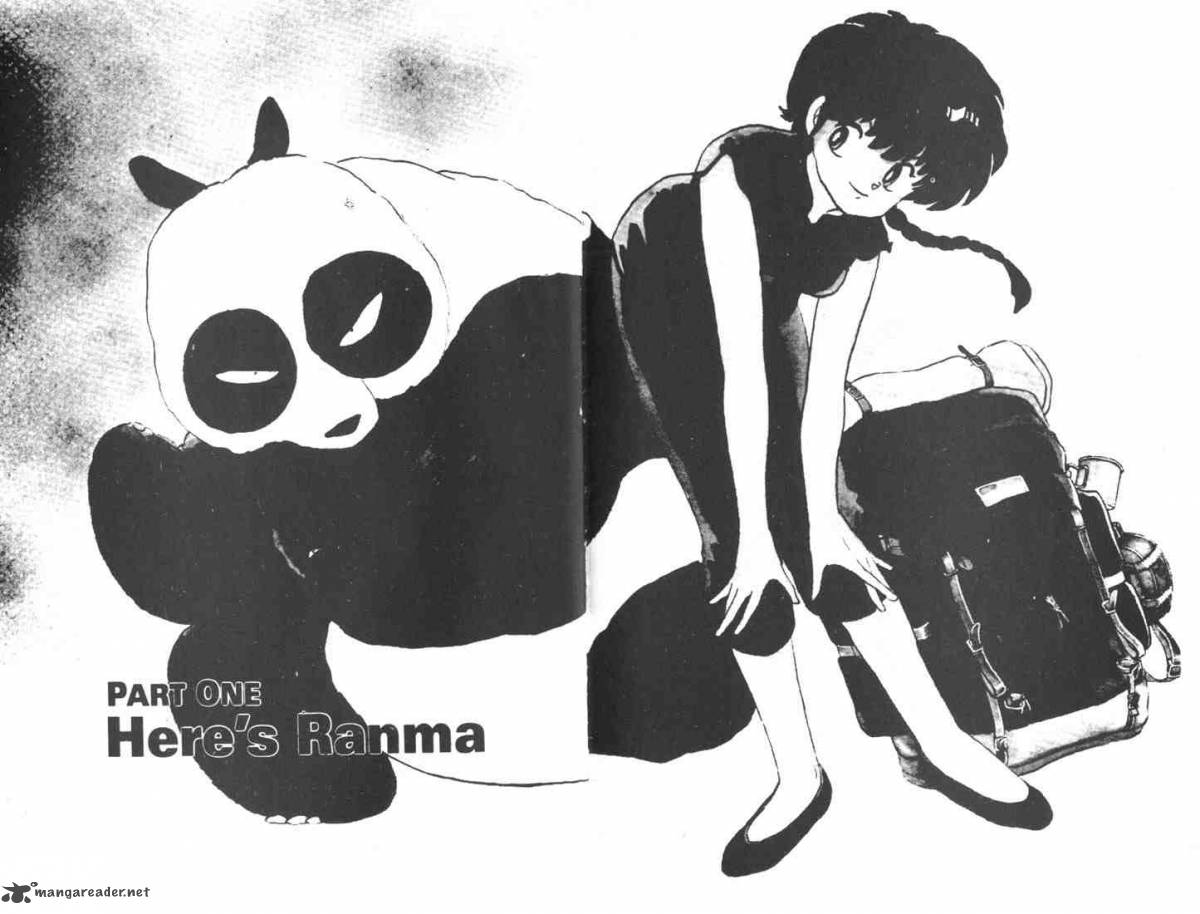

One of the first major manga American successes in the late 1980s/early 1990s was Rumiko Takahashi’s Ranma ½. Takahashi supposedly had determined to write a comic that would appeal more to girls than some of her earlier series, and that series couldn’t have been much more straightforward (if that’s the word) about its cross-gender ambitions. “Ranma” refers to the hero of the book; “1/2” refers to the fact that, due to an accident at a cursed spring, that hero spends a significant portion of his time as a heroine. Whenever he’s splashed with cold water, he turns into a girl; when he’s drenched in hot water, he turns back into a guy.

If that sounds like a preposterous premise for a series — well, that’s the least of it. Viz has just started to rerelease Ranma 1/2 in budget two-for-one volumes, and re-reading the beginning of the series again, it’s hard to express, right from the start, how completely, joyfully absurd it is. By page four, we’ve got Ranma (as a girl) racing up the street pursued by a giant panda bear — a giant panda bear who turns out to be Ranma’s father, Genma Saotome. At the same time that Ranma fell into the cursed spring that turned him into a part-time girl, Genma fell into a spring that turned him into a part-time panda. And a very cute part-time panda at that.

This labile approach to gender and species is mirrored in the book’s genre commitments. The narrative is devoted to a series of crushes/romantic entanglements interspersed with violent martial arts battles interspersed with gender switch hijink and a heaping helping of sexual farce.

Though Ranma is the titular star, he shares the spotlight with Akane Tendo, a young girl who loves martial arts, hates boys, and is kind of/sort of Ranma’s arranged fiancé at the behest of their parents. The two have hardly met before they’re engaged in a martial arts battle (with Ranma as a girl), and they’re hardly done fighting before they’re running into each other naked in the bath, where the hot water has changed Ranma back into a guy. This is but the first of many nude sexual teases, all the more giggle-inducing it’s unclear who the fan service is for. Are we looking at female bodies for male gazes? Male bodies for female gazes? Both for either? Or are there other possibilities? In one scene, female Ranma and Akane run into each other in the bath again, both naked, prompting Akane to deck him (or her.) “But you were both girls, right? Doesn’t that make it okay?” Akane’s older sister Nabiki asks. For Nabiki, the gender (and genre) changes ease or erase sexual tension. For Akane, though, the male/female switch makes all relationships potentially charged with polymorphous verve.

Ranma ½ as a whole leans towards Akane’s interpretation. In making a book aimed at both boys and girls, Takahashi doesn’t opt for a middle-of-the-road, appeal-to-everybody kind of story. Rather, she revels in the way that she can giddily bash boys’ genres and perspectives against girls’ genres and perspectives and come up with ridiculous risqué adventurous loopiness for all. Thus, upperclassman Kuno’s mano-a-mano desire to best Ranma in single combat for the hand of Akane slips inevitably into courtship, as the antagonist confusedly falls in love with Ranma’s girl form, thrusting flowers at her (him) with the same hostility/obsession with which he first went after him (her) with a sword.

As the first male-male martial arts rivalry in the book, the Kuno-Ranma rivalry/romance sets a blueprint for other encounters. When the next antagonist, Ryoga, shows up, his ill-defined desire for revenge (because Ranma stole bread from him at some point?) seems like it could just as easily be some other ill-defined passion. The slipperiness of motive fits into other slipperinesses; Ryoga too fell in a cursed spring, and when exposed to cold water he turns into an adorable baby pig. That pig wins Akane’s heart, and the Ryoga/Ranma battle ends when Akane drags off the irresisitibly neotenous ungulate to cuddle in her bed. So Ranma goes to get him out of Akane’s room, and there’s an epic battle with Ryoga-pig boucing around the room in an explosion of racing motion-lines. The cuddly-animal martial arts battle ends with Akane discovering that her little comfort pet has been replaced in her bed by a very embarrassed Ranma, the funny animal comic for kids morphing into a sex comedy with the same sort of audible “Bloosh!” that always greets the panda’s ascent from water.

Those easy substitutions — of genre for genre, gender for gender, species for species — are enabled by, or work as a metaphor for, the comics form itself. Each panel in a comic is a different, fractured moment. We see a picture of Ranma kicking here and a picture of Ranma punching there and we determine those are two images of the same person simply because we’re told they’re the same person. So you can call this pig and that human the same character if you’d like; who’s to stop you? Identity in comics is a convention — and if self is simply a trope, then so is gender, and even species. Comics don’t have to be for boys only, because in comics even boys don’t have to be boys only. Ranma ½ is its own cursed pond; you fall in and come out every which body, whether a boy reading girls comics, girls reading boys comics, or a panda reading both.