I think this is the first thing I published on Splice Today.

______

Most traditional economic theory is built around the concept of scarcity – the idea that there’s not enough stuff to go around. In The Accursed Share (1946), Georges Bataille inverts this; life, he says, is characterized, not by too little, but by too much. Life is excess—it pushes onto every bleak rock, every cranny; it spends itself in profligate sexual activity and in the ultimate profligacy of death. And it throws out unneeded economic activity; too much fat, too many children, too much grain in the stores, too many bodies in the street, too much creative energy shaking its collective tuchas on the YouTube videos.

For Bataille, it is the business of life and of society to consume this “accursed share.” The paradigmatic way to do this is through sacrifice; the burning of goods-or, better, of lives-with no recompense. Through sacrifice, Bataille argues, the blasphemous impulse to turn other creatures, other lives, into productive things, is reversed, acknowledged as false and evil. To respect the universe, abundance must be spent, not horded. The Aztecs, in burning men, honored life.

The bloody Aztec rituals were paradigmatic; the North American Indian custom of potlatch, on the other hand, was, for Bataille, a sinister travesty. In the potlatch, an Indian would give a valuable gift to a rival to demonstrate his own wealth and power. In response, a rival would have to give an even greater gift. This could go on and on, back and forth, and whoever ended by giving the greatest gift would show himself superior. Thus, squander was not in fact squander—the winner did not lose his gift, but instead traded it for prestige, or rank. Bataille thus notes contemptuously that potlatch “attempts to grasp that which it wished to be ungraspable, to use that whose utility it denied.” By turning sacrifice into rank, Bataille believed, potlatch turns, not a part, but the whole of the universe to a servile thing.

Potlatch as such is now practiced in only a handful of places, and (to be remorselessly PC) one has to wonder whether Bataille’s anthropological account really did the custom justice. Still, if Native Americans don’t exactly recognize Bataille’s potlatch, others, I think would. Who, after all, profligately spends time, energy, and resources in a remorseless quest for status and rank? Who grasps the sacred and turns it to the profane ends of thingness? Who wastes, not in the name of a sublime nothing, but in the pursuit of a soiled, excess something?

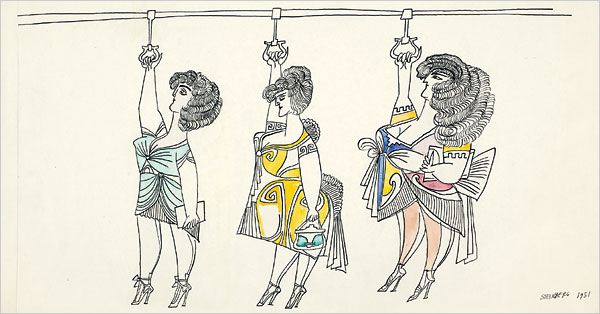

The answer is clear enough: in the modern day, the avatar of Bataille’s twisted potlatch is none other than the artist, in all his (or her) needy, self-deluding, miserly profligacy. The artist hunkers down with her (or his) materials, practicing, practicing, practicing, wasting life in the pursuit of an entirely useless form-and for what? Why, to be noticed, admired, proclaimed a genius-in short for rank. True, the least debased artists seek not some subcultural caché, but simply money. They are guilty only of the typical human failing; the desire to turn bits of life to things; to treat the sacred as a business proposition. Beyoncé and Rod Stewart are no more despicable than, say, Bill Gates, or your average carpenter. But by far the vast majority of artists foreswear (relatively) healthy capitalism for the putrid wallowing in essences; they desire to turn life itself (“authenticity”) into a bludgeon with which to beat their rivals. The Aztecs tore out hearts to offer to the sun god; artists pour out heart and soul and offer it to the Pitchfork reviewers.

Which isn’t to say that all artists are inevitably defiled. On the contrary, if any contemporary figure attains to Bataille’s ideal of pure sacrifice it is one particular kind of artist—that is, the failed artist. Note that by “failed” here, I do not mean the artist who has missed commercial success, but has underground cred or aesthetic bonafides, or who is discovered and lionized after his death. On the contrary. When I say, “failed” I mean “failed.” I mean an artist who profligately, copiously, obsessively works on creating objects that are, literally—by everyone and forever—unwanted. Creators of tuneless songs who never achieve dissonance; of ugly canvases too self-conscious to be outsider art; of doggerel verse too banal for even the high school literary magazine-in them, the excess of the universe is annihilated. Genius, love, life—they are exchanged for neither lucre, nor cred, nor beauty, but are instead simply thrown away. Failed art is permanently wasted. Squatting amidst the gross outpouring of sublimity, the ugly, the thumb-fingered, the clichéd piece of crap, is alone sacred.