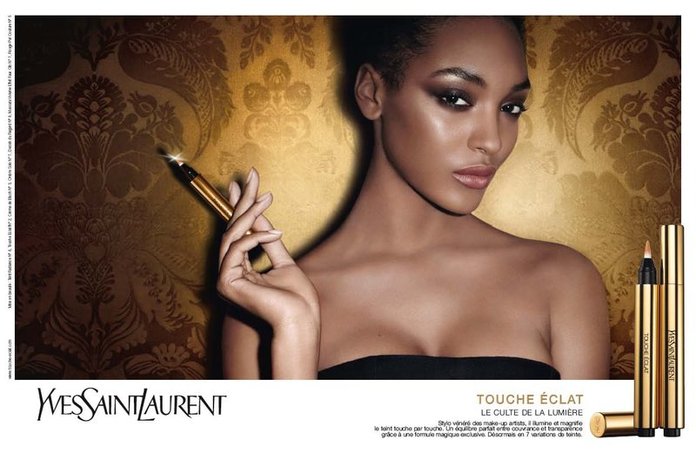

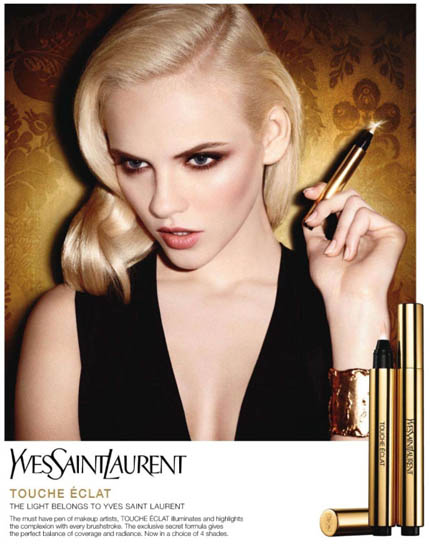

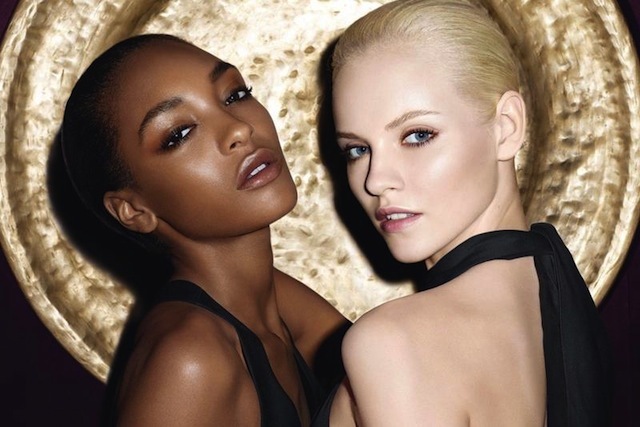

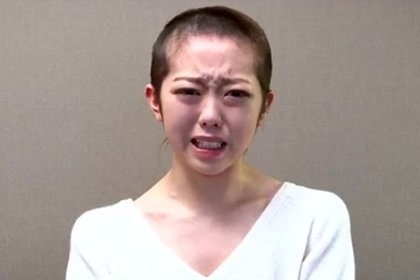

Last week Charles Reece, Sarah Shoker and I had a conversation in comments about authenticity, plastic surgery, commerce, make-up and other things. Along those lines, I thought it might be interesting to talk about this back-cover ad for from the May issue of Vogue for the Touche Éclat make-up pen, featuring models Jourdan Dunn and Ginita Lapina.

“Le Tent Touche Éclat covers imperfections while letting your natural radiance shine through,” according to the copy.

As that suggests, the ad, like a lot of fashion, is deliberately playing with tropes of naturalness and artificiality. The make-up pens stand in for cigarettes — which in turn stand-in for phalluses, so that applying make-up becomes, all at once, socially (not to mention physicaly) dangerous, a tease for a male(?) viewer and an assertion of sexual power. Moreover, the two women — with their similar smooth styling, poses, head tilts, and standard smoldering stares — double each other, artificially cloning the others’ look. White becomes mimicking of a (natural?) black, while black becomes a micmicking of a (natural?) white. The doubling creates a standard (everyone is doing it) and suggests there is no unitary standard (doubling is uncanny.) Similarly, the weird gold nowhere against which they pose contrasts with the simplicity of their outfits; Dunn’s black dress is so low cut that she’s au natural for all practical purposes, while Lapina appears in unadorned black (with plunging neckline.)

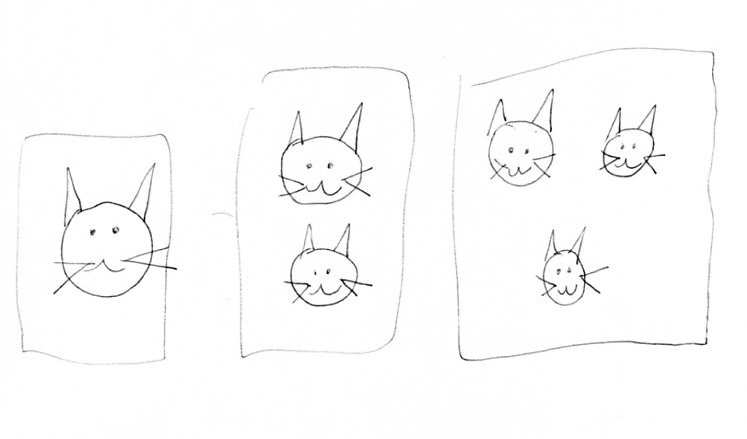

IN part, the ad uses the natural/artificial binary as a lever to commodify naturalness. Dunn and Lapina become multiplied, deindividualized icons — carefully arranged compositional elements in someone’s, or everyone’s, golden dream. The repetition of their diverse natural, individual selves tends to make those selves, in their naturalness and diversity, replicable, and therefore available and purchaseable. With makeup, you two can be as individual as them.

You need this individuality, or uniqueness, or (if you prefer) authenticity if the transaction is going to be appealing or exciting. It’s not just being able to purchase a replicable thing; it’s the sense that the replicable thing purchased is special. That’s the appeal of the interracial models. But it’s also the appeal of the inevitably controversial cigarette imagery. And, for that matter, of the connotations you set up when you put a black woman and a white woman together, each wielding a penis substitute — cultural discourses around prison butches and interracial lesbianism are buried, but not, imagery like this suggests, utterly forgotten. As Tom Frank has pointed out over and over, controversy and rebellion sell; nonconformity is the most exciting conformity of all.

The market, then, takes any form of authenticity or individuality, and turns it into an image of itself, so you’re buying back your own natural radiance to be applied artificially, or purchasing markers of rebellion (interracial mixing, lesbianism, cigarettes) just like everybody else.

Capitalism’s de-authentification of everything can certainly be depressing and constricting, demanding that women conform their real bodies to impossible standards (I’m sure the image here has been extensively photshopped, like all images in fashion mags.) On the other hand, though, it’s hard not to see some appeal in the artificiality as well. Where is this world we are being shown, where race is interchangeable, where deviant sexuality is glamourous and fabulous rather than marginalized and persecuted, where beautiful bodies float free of social stricture or even — as cigarettes become mere style icons — fear of cancer? It’s easy to say, well, interracial fraternization and even hints of lesbianism aren’t scandalous any more — but that “any more” is pretty recent. Forty years ago, this image would probably have been unprintable in a mainstream publication. Today, it’s being used to sell cosmetics.

If the problem with capitalism is that it makes rebellion conventional, then the upside of capitalism is that it makes rebellion conventional. And the way it does that, in part, is through a relentless assault on authenticity.There is no norm but the market, before whom the only differences that matter are desires, and all desires are equal. Everything is surface and style, which means that every proscription — against blacks, against gays, against smoking — is waved away as long as you are beautiful enough and have the right products.

That gold, glowing background, then, can be seen as capitalism itself — the mystic n-space that turns bodies and individuals into their own perfect replicas. The only morality there is that little bit of glowing glamor you can grab, the only pleasure the thrill of letting that glamor swallow the self in its brightness. Is disappearing into the brightness freedom, or is it nothing left to lose? It probably depends on what you had to lose in the first place, ow what you think you can get in exchange for your soul. Or maybe, as Waylon Jennings said in an authentic, wise song you can purchase in replicable digital form on I-Tunes, “Sometimes it’s heaven, sometimes it’s hell, sometimes I don’t even know.”