The index to the Comics and Music roundtable is here.

______________________

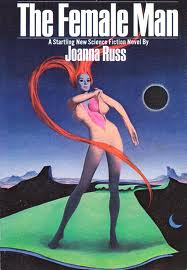

“There was no working title for the album. The record-jacket designer said `When I think of the group, I always think of power and force. There’s a definite presence there.’ That was it. He wanted to call it `Obelisk’. To me, it was more important what was behind the obelisk. The cover is very tongue-in-cheek, to be quite honest. Sort of a joke on [the film] 2001. I think it’s quite amusing.”

-Jimmy Page

On the one hand, the black object there in the center of the bourgeois family may indicate Zeppelin’s power and force, as Jimmy Page suggests — the God’s uncanny presence. The happy family dinner, the smiles, the upper-crust yachts in the background; the black finger in the center, with its calibrated, meticulous wrongness, reveals the cheerful 50s nuclear family as paper-thin pasteboard. Zeppelin’s mere presence reveals and knocks apart their uncanny inanity.

Robert Plant was in a car accident on the Greek island of Rhodes before the recording of Presence, and ended up in a not especially sanitary hospital. He recalled:

I was lying there in some pain trying to get cockroaches off the bed and the guy next to me, this drunken soldier, started singing “The Ocean” from Houses of the Holy.

Led Zeppelin was the Beyoncé of its day; ubiquitous and omnipresent. Page doesn’t sound quite like he’s reveling in that omniPresence, though. On the contrary, with the cockroaches and the pain, there’s something decidedly Gothic about this encounter with a drunk foreign ventriloquist doppelganger. A broken has chased him down across the globe in order to mirror, with pitiless vacuity, his broken self.

Isn’t there, then, also a kind of vulnerability, a diminutive interrogative, in the way the object twists itself around, bending its non-face, half coy, half nervous, to the giant mannequins who loom above it? The smiling, cheerful normality of the adults and the blank featurelessness of the children, all captured in high focus, suggest a certain feral threat — a hungry falseness. Perhaps that hungry falseness is ours, too, when the family is gone and we replace them around the Object.

Zeppelin may be that object itslef, but its objectness has passed out of Zeppelin’s control. It is now a public totem, doomed to ingratiate even at its most idiosyncratic, and individual — or, as Tom Frank would have, especially at its most idiosyncratic and individual. Like Plant regaled by his own tunes at the butt end of noplace, celebrity and self wait everywhere, mouths open. The Object is not crushing all around it. It is simply surrounded.

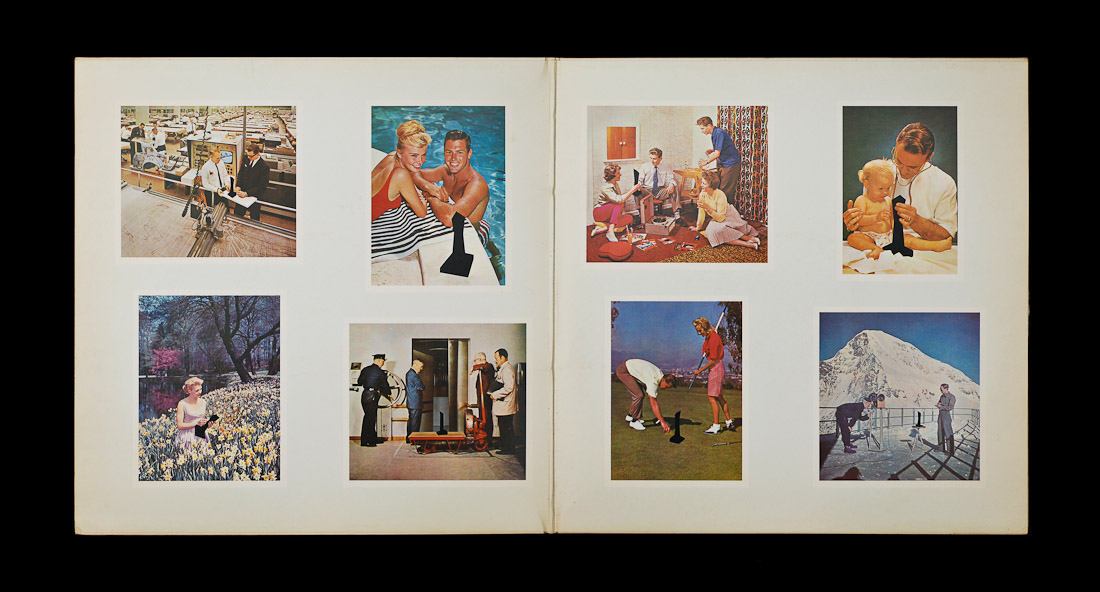

Perhaps, though, Zeppelin isn’t the black Object — or at least, not just the black Object. After all, the images chosen for the album art — the cheerful, healthy couple at the pool; the immaculate golf green; the serious researchers investigating — all seem picked in no small part not just for their blandness, but for their bland non-blackness. The normality on offer, the default scrubbed cheer, is white — insistently so in the dress of the woman amidst the flowers, or the snowy peak of the final image.

The photographer, though, is not filming the snowy peak, but the black Object, just as the happy family is turning from their dull (Pat Boone?) records to the new twisted, exciting thing.

Again, that new twisted exciting thing could be Led Zeppelin itself. But the tableaux could also be seen as a kind of re-enactment, or parody, of Zeppelin’s own relationship to racial performance. Plant’s weirdly abstracted, soulless moans at the beginning of “Nobody’s Fault But Mine” as the sturm und drung flatten the gospel humility under towering psychedelic mannerisms, just as the miniaturized and humble object disappears into a warehouse of cerebral study in the upper left hand image. Plant’s eager I’m-James-Brown-no-really emoting on “For Your Life” seems to reach for swagger and cred in the same way that the baby reaches for the black object phallicly positioned between its legs in the upper right. And given the Elvis-shake on “Candy Store Rock,” the doctor there, carefully handling the Object’s tip, might be seen as representing an older generation of borrowers, passing on the appropriation to the curious but willing infant acolytes.

From this perspective, it’s not the Object which is uncanny, nor the aggressively smiling giants looking down on the Object, but rather the juxtaposition of the two. The weird funk funeral march of “Achilles Last Stand,” with its drifting hippie lyrics and Plant howling like a ghost being scraped across steel girders, is a kind of photonegative of that smiling couple looking at the thing; satyrs running through the iron city, rather than warbots dancing in a midnight glade. Zep’s distance from its sources is figured in the images, and perhaps in the music, not as authenticity but as wrongness. The black Object haunts the mountain and the white mountain haunts the Object, in the iterated symbiosis of the dead.

Comics generally represent motion through repetition; the same body or figure is drawn in one space and then another to show the passage of time. Music, on the other hand, seems to fill space; it’s everywhere and nowhere. Its repetitions through time are both insistently present and invisible.

The Object seems to ambivalently take part in both these structures. It could be seen as moving from location to location; starting the week with dinner at the yacht club and finishing up in a schoolroom. Or it could be seen as inhabiting all paces simultaneously; a broadcast received at once by the poolside, the bank vault, and the golf course. Or perhaps it could be seen as inverting both these options. Maybe it’s the Object that sits in one place, while the smiling people and their hollow world flicker and hum around it.

The image above is the only one where there are two objects, or an object and its image. The teacher seems to be trying to hear or see the boy’s mind; the drawing on the wall could be his thought bubble, or hers. In either case,or neither, it’s someone’s duplicated representation of a thing which is not a thing, sort of like a comic about music.