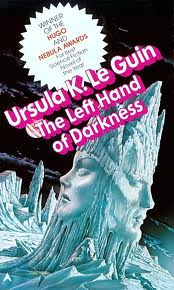

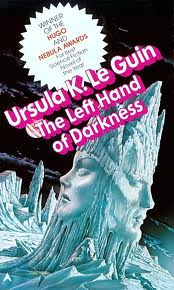

Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel The Left Hand of Darkness is best known for its imaginative take on gender — the inhabitants of the planet Gethen (Winter) are human-descended hermaphrodites, who become male or female (depending on their partners) only during a brief mating cycle (called kemmer) every month.

For Le Guin, though, the ambisexuality of the Gethenians is about much more than just sex. As she says (through the mouth of a Terran-normal human observing the Gethenians,) the structure of the kemmer cycle rules the Gethenians; all their stories and culture is focused on it. This, she says, is relatively easy for outsiders to understand. But

For Le Guin, though, the ambisexuality of the Gethenians is about much more than just sex. As she says (through the mouth of a Terran-normal human observing the Gethenians,) the structure of the kemmer cycle rules the Gethenians; all their stories and culture is focused on it. This, she says, is relatively easy for outsiders to understand. But

What is very hard for us to understand is that four-fifths of the time, these people are not sexually motivated at all…. Consider: Anyone can turn his hand to anything. This sounds very simple, but its psychological effects are incalculable…. Consider: A child has no psycho-sexual relationship to his mother and father. There is no myth of Oedipus on Winter….. Consider: There is no unconsenting sex, no rape.

Gethenians, Le Guin goes on to make clear in the rest of the book, are not ruled by the dualism or binaries which structure our thought. Perhaps in part for that reason, they have no war.

I say “perhaps” here advisedly — Le Guin is careful not to absolutely link the absence of masculinity to the absence of violence. There are other possible reasons for the lack of warfare; Gethen is an extremely cold planet, and its inhabitants are in a constant struggle for survival — their battle against the cold is so all-consuming and fierce that they have had little time to develop large scale states or armies. They do, however, have assassinations, and murders, and torture, and even occasional small battles. During the time of the novel, two Gethenian nations have even gotten large enough and powerful enough that it looks like a border dispute might turn into war.

Still, with all these caveats, the fact remains — the Gethenians don’t have men, they don’t have sexual violence, and perhaps not as a direct result, but not incidentally either, they don’t have glory of arms, and they don’t have war.

The link between gender and violence is subtly emphasized on another level as well. The story of the novel focuses not just on the Gethenians, but on a visitor to their planet. Genly Ai, a Terran man, has come to Gethen as a representative of the Ekumen, a pan-galactic organization of cultural traders, or sharers. Genly has come alone on his mission specifically so that the Gethenians do not feel pressured or afraid of him. The Ekumen seek no control; they completely eschew force. When a world accepts their overtures, they simply open communication and begin exchanging knowledge and technology. It’s like the benevolent Star Trek Federation — if the Federation were completely non-violent.

It’s not just Gethen which does not have war, then — it’s the novel itself. And just as Gethen’s lack of warfare is linked more or less explicitly to the gender of its people, so the lack of warfare in The Left Hand of Darkness seems linked, more or less explicitly, to the fact that its writer is a woman.

The book is, certainly, a kind of feminist response to, or critique of, the way that sci-fi generally represents, or imagines, the meetings of cultures. As I’ve said in a number of posts, for sci-fi the meeting of cultures is very often both violent and explicitly imperialist. In fact, from the War of the Worlds on up, the point of sci-fi often seems to be to dramatize, or rationalize, or displace, imperial narratives of conquest. In The War of the Worlds, or John Christopher’s Tripod Trilogy, or Alun Llewellyn’s The Strange Invaders, contact between different cultures is about conquest, one way or the other. Difference means subjugation or extermination; all binaries are unstable.

Le Guin’s world, again, has no binaries. And yet, the novel about a people with no gender difference is in the end a celebration of difference. This is stated perhaps most explicitly near the end of the novel, when Genly Ai’s Gethenien companion, Estraven, goes into kemmer. The two are traveling across a gigantic frozen ice sheet; there is no one else around. Estraven is driven to mate, but the only one to mate with is Genly Ai. Yet the two do not have sex, and Genly explains why:

For it seemed to me, and I think to him, that it was from that sexual tension between us, admitted now and understood, but not assuaged, that the great and sudden assurance of friendship between us rose: a friendship so much needed by us both in our exile, and already so well proved in the days and nights of our bitter journey, that it might as well be called, now as later, love. But it was from the difference between us, not from the affinities and likenesses, but from the difference, that that love came; and it was itself the bridge, the only bridge, across what divided us.

Difference, then — between races, between genders, between individuals — is not a thing to be erased or denied, but a place to live upon, and the only ground for life and for love.

On the one hand, Le Guin’s alternative to imperialism — basically, love one another — seems too easy, or even glib. The Ekumen is — like that old Federation — simply too good to be true. Certainly, the history of the U.S. seems to caution pretty strongly against believing empires when they say that they are only empiring for the good of those empired.

And Genly Ai himself seems too good by half. His sexual abstention, which gives the pivotal scene above much of its force, seems hard to credit when looked at more than cursorily. He has, supposedly, been on Gethen for more than a year; he’s planning to be there for much longer; he does not seem to be intimate with anyone back on his home planet, or with his colleagues circling in stasis in the ship above. Has he just decided to never have sex again for the rest of his life — or at the least for many years? That’s a bit hard to swallow, especially given the history of imperialism and sexuality on the one hand, and the taboo-less ease of sex in the Gethenien culture on the other. What’s even harder to credit is the fact that throughout the entire book, Genly basically never expresses any sexual desire; not for the Getheniens around him, not for anyone in his past, not looking forward to the future. He is preternaturally continent. Le Guin — like Genly himself — seems to feel that not only gender, but sex, must to be verboten if difference is not to result in violence.

But even with those caveats, Left Hand of Darkness still manages something pretty rare at the time, and I think rare still — a sci-fi cross-cultural friendship which feels both genuinely cross-cultural, and genuinely like friendship. And, the book suggests, one of the greatest gifts of that friendship, or that difference, is to give you a sense of your own difference or individuality. There’s a lovely moment in the book when Genly Ai suddenly sees his own masculinity — his competitiveness, his investment in his own strength, his honor — from the vantage of his relationship with Estraven, as a cultural construct, a burden, even, that he can put down if he chooses. And there is also the moment when we get Estraven’s view of him.

There is a frailty about him. He is all unprotected, exposed, vulnerable, even to his sexual organ, which he must carry always outside himself; but he is strong, unbelievably strong. I am not sure he can keep hauling any longer than I can, but he can haul harder and faster than I — twice as hard…. To match his frailty and strength, he has a spirit easy to despair and quick to defiance: a fierce, impatient courage. This slow, hard crawling work we have been doing these days wears him out in body and will, so that if he were one of my race I should think him a coward, but he is anything but that; he has a ready bravery I have never seen the like of.

This is certainly about Genly Ai in particular, as an individual — but it’s also about his masculinity, which is, in Estraven’s eyes, not foolish or violent, but vulnerable and strong and gallant. Le Guin refuses a story in which the colonizers are evil and must be erased, just as she refuses one in which the colonized are barbarians and must be erased. Rather, she suggests, when you erase the other you erase yourself; what eyes can see you if you poke out everyone else’s eyes? The Left Hand of Darkness may not be convincing in every respect, but it is, at the very least, a useful reminder that difference is the basis, not just of genocide, but of love as well.

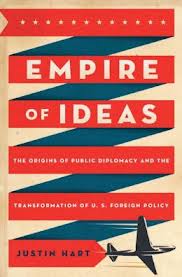

I recently had an article in the print edition of Reason on Justin Hart’s Empire of Idea, a book about America’s efforts to influence world opinion. Peter Suderman interview me for a profile to run beside the article…but of course, I was over verbose, so most of my responses got cut. Peter, though, has kindly gave me permission to run the whole thing here instead.

I recently had an article in the print edition of Reason on Justin Hart’s Empire of Idea, a book about America’s efforts to influence world opinion. Peter Suderman interview me for a profile to run beside the article…but of course, I was over verbose, so most of my responses got cut. Peter, though, has kindly gave me permission to run the whole thing here instead.