I don’t know if it was so much [Johnny Cash’s] music per se that drew me to him; it was more his overall persona….

—Rick Rubin, Interviewed on NPR’s Fresh Air, February 2004

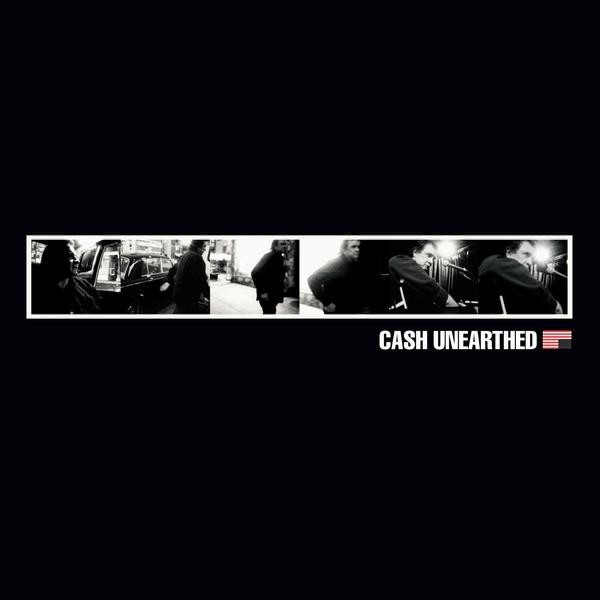

Unearthed, the five-CD collection of outtakes and unreleased material from Johnny Cash’s last 10 years with American Recordings, comes in a box as black and stark as Cash’s tormented soul. The sleeves are made of CD-scratching cardboard, as rough and uncompromising as Cash’s famously raised middle finger. The shrink wrap is tough and tenacious, as tough and tenacious as….

Well, you get the idea. Cash is a serious artist and it takes a virile, forward-looking, serious company like American to provide his music with the extremes of over-packaging it deserves. Old, stodgy labels like Columbia and Mercury hadn’t known what to do with a complex iconoclast like Cash — it took Rick Rubin, American’s founder, to see the greatness in Cash and act on it. The liner notes to Unearthed gleefully quote Nick Tosches, who claimed that “Johnny Cash at 61 was history, an ageing, evanescent country music archetype gathering dust in a forgotten basement corner of the cultural dime museum.” It wasn’t until Cash’s first 1994 album on American that the singer was granted “the imprimatur of ageless cool.”

Or so the story goes. Johnny Cash’s career was indeed in a slump in the eighties and early ‘90s — enough of a slump that he thought he might cease recording altogether. But he was hardly as irrelevant as Tosches and Rubin make him out to be. In fact, in 1993, the year before his first American release, Cash made a much promoted and discussed appearance on the final track of U2’s Zooropa. Rubin didn’t have to be a genius to figure out that there was an audience for Johnny Cash’s work — all he had to do was read the papers.

Nonetheless, American has spilled a lot of ink insisting that Cash’s career would have been over without Rick Rubin. The point of this strategy seems to be to make Cash and American go together like ham and eggs, or music-industry and slimeball. Usually a label promotes the artist, but with Cash and American, something like the opposite has occurred. Cash’s first album with the company was actually named American Recordings (as Cash quipped on one of his final tours, “the album American Recordings on the American Recordings label, recorded right here in America”). His other albums also give the American name unusual prominence and, continuing the trend, the back of Unearthed features the labels’ upside-down flag symbol alone on a black background. Little wonder, then, that Unearthed’s liner notes exclaim that Cash’s first album with American was “as stark, dark, and elemental as the stunning cover photo,” as if it’s some sort of compliment to Cash to have his work compared to a publicity shoot. Still, there’s a certain logic here: if the label is as important as the artist, then it makes sense that the packaging is as important as the music.

For this particular promotional strategy, the blame must rest with Rubin himself, who not only signed Cash, but also produced each of his albums. Rubin was already quite well-known before his work with Cash, in large part because he had worked on a number of landmark rap and metal albums: most notably the classic early records of L. L. Cool J, the Beastie Boys, and Slayer. But Rubin’s notoriety was also a function of assiduous self-promotion. With the Beastie Boys, in particular, Rubin pushed himself forward with unusual enthusiasm, touring with the group, appearing in videos, and adopting the rap moniker DJ Double R. According to The Vibe History of Hip Hop, Rubin considered himself a member of the band. If he believed his own hype, however, the Beastie Boys did not, and when they left his then-label Def Jam, they left Rubin behind as well.

As far as I know, Rubin has never appeared on stage with Cash, but he hasn’t exactly retired into the background either. Unearthed is presented as a collaboration between the two men, who are portrayed as something very close to equal artists. “This is the story of what happened when the man with the beard [Rubin] met the Man in Black,” the liner notes intone. Their encounter is then described in the portentous language of trashy romance novels — Cash’s former manager is quoted as telling Rubin ‘You could see the sparks flying between you two. There was such an immediate, powerful connection,” to which Rubin adds “It felt like we connected on some level other than talk.” Cash’s recollection is a bit more tongue-in-cheek. “You know, I’d dealt with the long-haired element before, and it didn’t bother me at all. I find great beauty in men with perfectly trained beards and groomed faces — or grooved faces, or whatever it is.”

Cash was intimately involved in the production of the box set before his death last September, and he’s clearly both grateful to Rubin and willing to share the spotlight with him. And there is no doubt that Rubin did revitalize Cash’s career, basically by marketing Cash the way he had marketed rap and metal acts — that is, by making Cash a dangerous outsider, a loner, an outlaw. Gone was the Johnny Cash whose biggest hits had been jokey novelty records like “A Boy Named Sue” and “One Piece at a Time”. In his place was, as the notes put it, “a dark troubadour with a troubled past who had sinned and been redeemed.” The first song on the first American release, “Delia’s Gone,” was a particularly vicious murder ballad — the video featured Cash killing model Kate Moss. Ten years before, “the dark troubadour” had appeared in a video for his song “Chicken in Black” wearing a blue-and-yellow mock-superman suit.

Obviously, Rubin didn’t invent the “dangerous loner” image for Cash, who had been singing about shooting people since the ‘50s. The American publicity merely emphasized this aspect of his persona with stark, moody, black-and-white album art and stripped-down production — especially on the first release, which featured Cash alone and unaccompanied for the first time in his career. Whatever the publicity material said, of course, Cash continued to record goofy stuff alongside the doom-and-gloom numbers. “The Man Who Couldn’t Cry” from American Recordings, “Mean-Eyed Cat” from Unchained, and, Cash’s heavenly duet with Merle Haggard on Solitary Man’s “I’m Leavin’ Now” are all glorious examples of Cash’s lighter side — wise, witty, and very funny. None of these cuts is represented on Unearthed’s fifth disc, a “Best of American” compilation which is tilted heavily towards his more solemn numbers — “Delia’s Gone,” “Hurt,” “I Hung My Head,” and the really annoying “Bird on a Wire” (Leonard Cohen’s clumsy ramblings do not benefit from Cash’s gravitas: the set also includes a fully orchestrated and even more lugubrious version.) Still, the other Unearthed discs contain a fair share of lighter material, including a jovial discussion of substance abuse in “Chattanooga Sugar Babe” and the unaccompanied “Two-Timin’ Mama,” perhaps the one American cut that most clearly evokes Cash’s Sun sides.

So all well and good: Cash is doing what Cash does, and Rubin has realized that young hipsters think it’s cooler to kill people than to laugh — or, perhaps more charitably to everyone, Rubin simply had the vision to give Cash a marketing budget, something the singer had been denied for years. Rubin, however, has not been satisfied with merely contributing to Cash’s commercial Renaissance. Instead, Unearthed’s liner notes insist that Cash’s resurgence has been aesthetic as well as critical. In explaining why he approached Cash, for example, Rubin says “I’d been thinking about who was really great but not making really great records…and Johnny was the first and the greatest who came to mind…Someone…who didn’t seem inspired to be doing his best work right now.” Rubin also says that his biggest challenge with Cash was getting the singer to see each recording date as special, rather than as just another album. The implication of all this, of course, is that the material on Mercury which Cash recorded in the early ‘90s was a series of prefabricated knock-offs.

Au contraire. The Mercury material is great — not every cut, of course, but the hit-to-miss ration isn’t significantly worse than on the American albums. At Mercury, Cash mostly worked with producer Jack Clement— a longtime friend — and he sounds relaxed and inventive. Indeed, his best material on Mercury is as good as anything he’s ever done. The duet-heavy Water From the Wells of Home from 1988 is perhaps the stand-out, featuring the lovely “Where Did We Go Right” with his wife, June Carter Cash; and the tough, vindictive “This Old Wheel” with Hank Williams Jr. Best of all, though, is the utterly bizarre “Beans for Breakfast” from 1991’s Mystery of Life, in which Cash explains that “the house burned down from the fire that I built in my closet by mistake after taking all those pills, but I got out safe in my Duckhead overalls.” Significantly, Cash never said that his work with Mercury was slick studio product: he only said, with great frustration, that the label wouldn’t promote it.

In this context, the most impressive thing about Unearthed is not how distinctive the American recordings are, but rather how much of a piece they seem with the rest of Cash’s oeuvre. For the truth is that each of the much-ballyhooed strengths of the American years — the surprising song selection, the challenging duet partners, the varied settings, and even the reinvention of Cash’s image — have all been typical of Cash’s career throughout. This is a man, after all, who started out as a rockabilly performer in the Elvis/Carl Perkins mode, appeared at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, was associated with the Outlaw country movement in the ‘70s, showed up on Emmylou Harris’ seminal Roses in the Snow album in 1980, and had his last hit record with the Highwaymen supergroup in 1985. Along the way, he recorded songs by everyone from Ray Charles to Bob Dylan to Kris Kristofferson to Bruce Springsteen to the Rolling Stones, hosted an eclectic television show, and released protest songs, concept albums, and a novel.

Cash, in other words, was always experimenting, and it is this aspect of his work that Unearthed puts center stage. It’s an odds and sods collection, so not everything works — a couple of tracks with a mediocre blues band are a mess; Joe Strummer sounds badly outclassed when he sings with Cash on Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song”; the version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” with organ is cluttered rather than sweeping; and I’m forced to admit that Cash’s austere renditions of hymns on disk four grow wearisome on repeated listening. That leaves, however, quite a lot of impressive music. The first disc in particular shows what a great idea it was for Cash to record alone and unaccompanied — an idea the singer had had some time ago but had been unable to sell until Rubin came along. All the interpretations are lovely: Billy Joe Shaver’s wistfully hopeful “Old Chunk of Coal,” and Cash’s own love letter to his wife, “Flesh and Blood,” are particularly fine. On the rest of the set, the duet with June is, as always, a high point; Cash’s baroque cover of his friend Neil Young’s “Pocahontas” (with mellotron) is also pretty great. Introducing Cash to Nick Cave was an obvious move, but it works wonderfully; Cave adds a touch of out-of-place gothic glee to “Get Along Home Cindy” which almost upstages the master. My absolute favorite track, though, is Cash’s short, sweet version of “You Are My Sunshine.” The song is a fusty piece of schmaltz which I’ve never liked very much, but Cash’s bleak quaver turns it from a greeting card into an agony of grief and loss.

Certainly Cash knew about grief and loss. This is the aspect of his work which — with his long illness, the death of his wife last May, and the success of the single and especially the video for “Hurt” — has been most in the news for the past couple of years. To me, though, the fact that Cash was able to change, to learn, and to take risks with his life and art for more than forty years is far from sad. One of those risks was to record with Rick Rubin, who led him to new songs, new people, new audiences, and new approaches to recording. Rubin, Cash himself, and the public all benefited from their collaboration. But I have no doubt that if Cash had not had the opportunity to take that particular chance, he would have taken another one. Even had the Man in Black never met the man with the beard, Cash’s story would still be one of the happiest in American music.

_________

A version of this essay ran at the Chicago Reader way back when.