One of the recurring themes of Bart Beaty’s Comics vs. Art is the way that art is always on top — sexual connotations very much intentional. Art, Beaty argues, is insistently seen or figured as rigorous masculine seriousness; comics is relegated to the weak feminine silliness of mass culture. Thus, Beaty says:

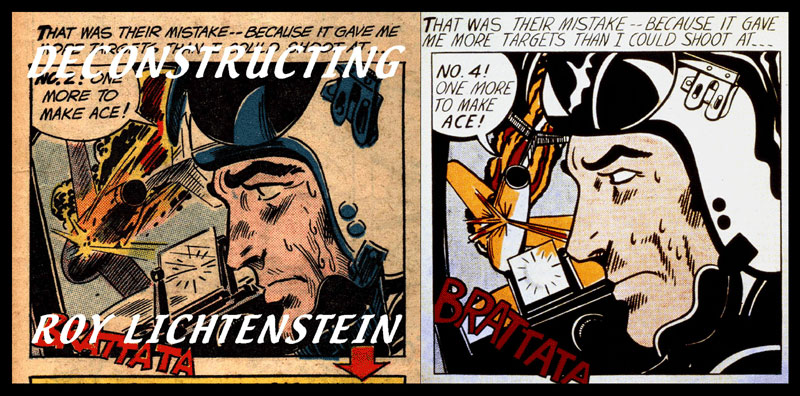

Lichtenstein’s paintings failed to rise to the level of aesthetic seriousness. The core problem was the way pop art foregrounded consumerism — a feminized trait — through its choice of subject matter.

Beaty goes on to argue that Lichtenstein was eventually recuperated for high art by emphasizing his individual avant garde genius — in other words, by claiming that he transformed comics material from feminine to masculine. Either way, Beaty argues, whether pop art wins or loses, comics are the feminine losers. For Beaty, the anger at pop art, therefore, is an anger at being feminized. In this context, the fact that the Masters of American Comics exhibition focused solely on male cartoonists was not an accident; rather, it was comics rather desperate and certainly contemptible effort to establish its high art bona-fides through an acculumulation of phalluses, and a careful exclusion of those other much-denigrated bits.

Beaty’s analysis is convincing — but he does perhaps gloss over an important point. That point being that, while it may often be figured as masculine in relation to comics, high art’s gendered status in the broader culture is, in fact, extremely dicey. For example, in Art and Homosexuality, Christopher Reed notes that Robert Motherwell, a married heterosexual, was rejected for military service on the grounds that being a Greenwich Village painter meant that he must be gay. In other words, at that time art was so thoroughly unmasculine that artists were almost by definition unmanned.

If art could be seen as effeminiate, comics as mass culture could be seen, in contrast, as normal, robust — as manly, in other words. Thus, Beaty relates this anecdote about cartoonist Irv Novick and Roy Lichtenstein.

[Novick] had one curious encounter at camp. He dropped by the chief of staff’s quarters one night and found a young soldier sitting on a bunk, crying like a baby. “He said he was an artist,” Novick remembered, “and he had to do menial work, like clearning up the officers’ quarters.”

Novick was one of the artists whose work Lichtenstein later copied with such success. Beaty correctly reads the anecdote as an effort to feminize Lichtenstein — a kind of revenge for the way in which Lichtenstein feminized Novick. However, Beaty doesn’t really consider the extent to which this feminization of Lichtenstein is successful because high art is already feminized. The anecdote is effective in no small part because artists like Motherwell were always already gay until proven otherwise — and often even if proven otherwise.

The point here is that the gendered relation between art and comics is not necessarily always about masculine art taking advantage of feminine comics and comics responding with resentment at being so feminized. Rather, on the one hand, comics’ antipathy to art is often tinged with contemptuous misogyny — a denigration of high arts femininity. R. Crumb’s loud denunciations of high art, for example (or Peter Bagge’s) are inevitably tinged with the insistence that artist’s are effete fools, distanced from real life in their ivory towers.

On the other hand, high arts’ interest in artists like Crumb or Novick often seems inflected with a kind of envy or desire. Certainly, Lichtenstein’s work, and pop art in general, can be seen as a campy appropriation of mass culture to feminize the often quite homophobic art world, particularly in contrast to the desperate masculinity of Ab-Ex. But Lichtenstein’s appropriations can also, I think, be seen as a performance of desire for masculinity — a bittersweet effort to capture comics’ masculine mojo while acknowledging his distance from it.

I don’t think that these readings are necessarily mutually exclusive. But I do think that recognizing them both as potentials creates possibilities that Beaty doesn’t really wrestle with. If art is not masculine (always) and comics is not feminine (always), then it’s much more difficult to see them as polarized (always.) Rather than art elevating, exploiting, or denigrating the hapless, accessible body of comics, art and comics start to look more alike — both occupying unstable cultural positions in which, at least historically, constant assertions of masculinity have been seen as vital to prevent a collapse into a devalued femininity. From this perspective, Comics fights Art not because the two are so different, but because their cultural positions and anxieties are so much the same.

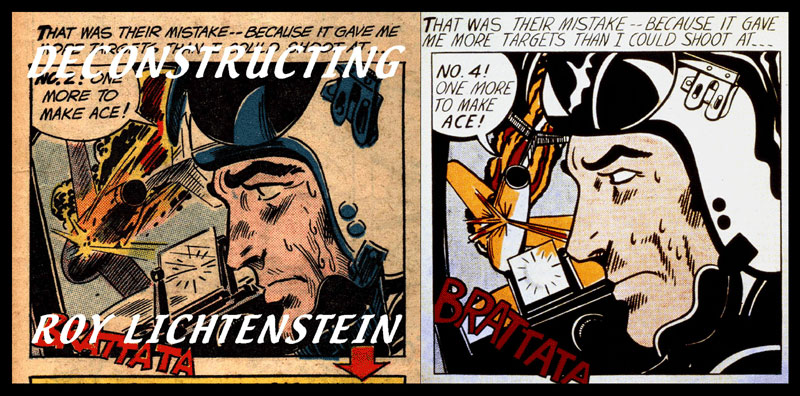

A Russ Heath panel and the Roy Lichtenstein painting based on it.