In a recent post on Philip Marlowe, Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that Chandler’s misogyny is (too) intimately tied to his vulnerability, or fear therof. Coates points to the way that Marlowe turns Carmen Sternwood out of his bed while sneering out lines like “It’s so hard for women—even nice women—to realize that their bodies are not irresistible.” Marlowe’s imperviousness to feminine wiles is connected both to his manliness and to his contempt for femininity.

Coates goes on to say this:

I think to understand misogyny one has to grapple with the conflict between male mythology and male biology. There is something deeply scary about the first time a young male experiences ans erection. All the excitement and hunger and throbbing that people is there. But with that comes a deep, physical longing. Whether or not that longing shall be satiated is not totally up to the male.

Erection is not a choice. It happens to men whether they like it or not. It happens to young boys in the morning whether they have dreamed about sex or not. It happens to them in the movies, in gym class, at breakfast, during sixth period Algebra. It happens in the presence of humans who they find attractive, and it happens in the presence of humans whom they claim are not attractive at all. It is provoked by memory, by perfume, by song, by laughter and by absolutely nothing at all. Erection is not merely sexual desire, but the physical manifestation of that desire.

Men hate women, therefore, because men are supposed to be in control, and their plumbing prevents that control.

I think this is perhaps a little too pat; biology-as-truth is, after all, its own mythology, and one that can (and is) also often put to misogynist ends. But putting that argument aside for the moment, I think Coates is in general correct that manliness is defined by control, and that that control is often structured in terms of control-over-biology, or the body, which is then itself always feminine, or threatening to drag one down into the feminine. Manliness is cleanliness is control is unbodiedness, so that the only real dick is the dick that is secure and private.

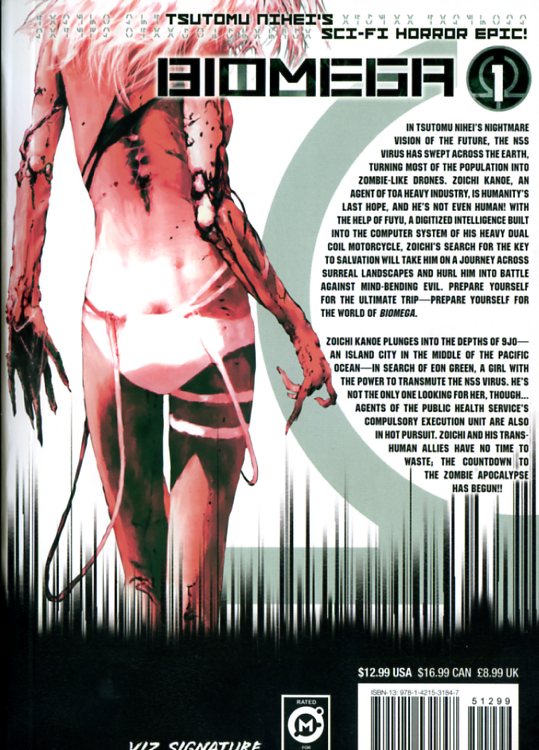

If Philip Marlowe read Johnny Ryan’s Prison Pit, you have to think that he would, therefore, be horrified not by its violence or its sadism, but by its messy embodiment — and, therefore, by its unmanliness.

Ryan’s work is, of course, generally thought of as a kind of reductio ad absurdum of frat boy masculinity. Prison Pit is a hyberbolic, endless series of incredibly gruesome, pointless, testosterone-fueled battles with muscles and bodily fluids spurting copiously in every direction. It is as male as male can be.

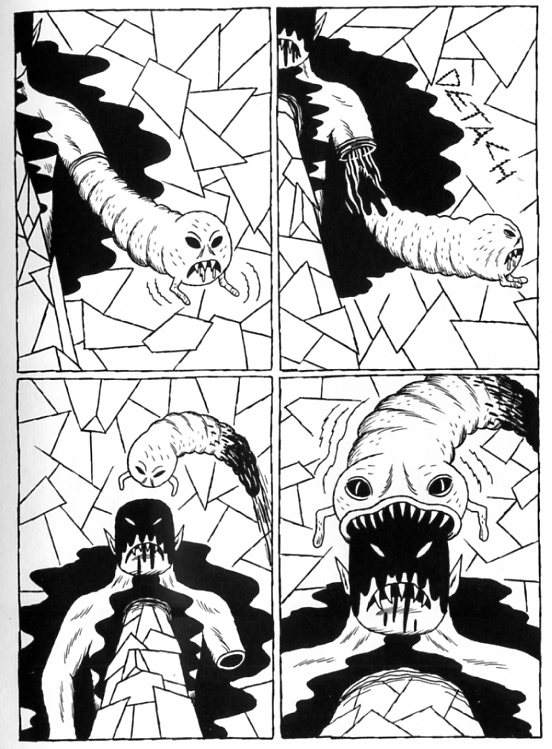

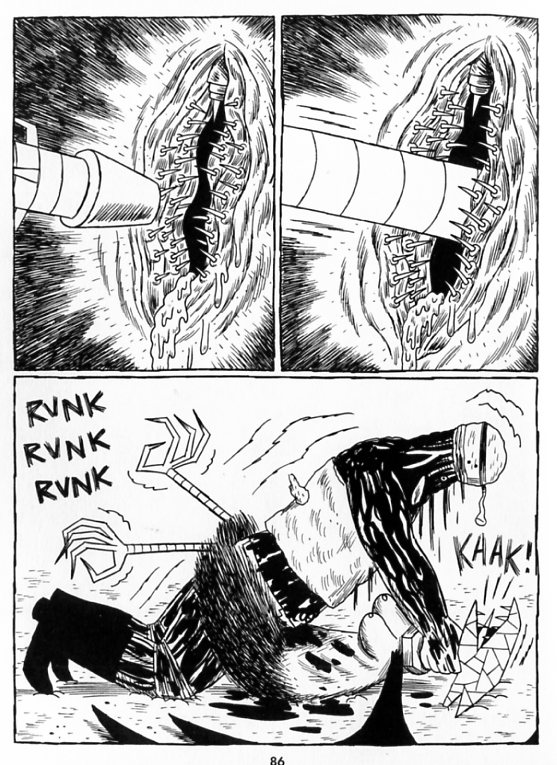

And yet…while Prison Pit is certainly built out of male genre tropes, its vision of masculinity and of masculine bodies is — well, not one that Raymond Chandler would call his own, anyway. That image above, for example, shows our protagonist as his disturbingly phallic left arm oozes up and off and devours his head. Far from being a private dick, that’s a very public and very perverse act of masturbation — and one that is hardly redolent of bodily control.

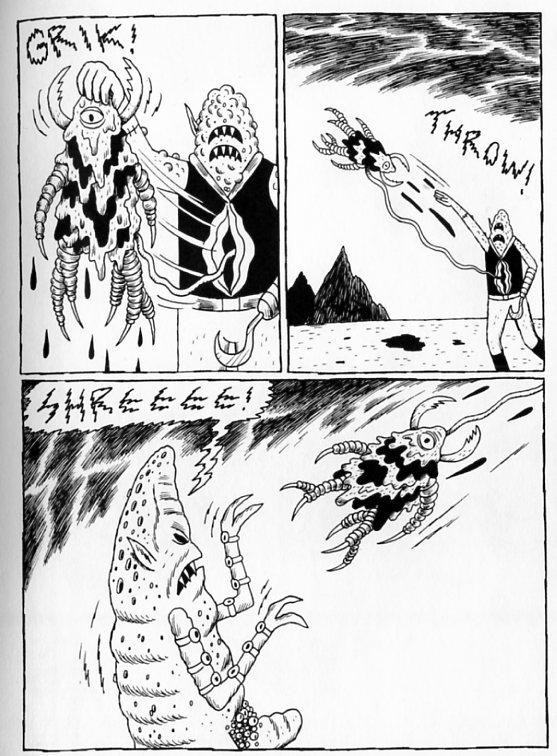

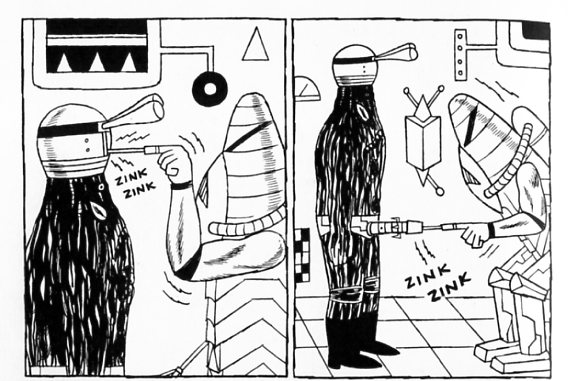

This sequence, while vivid, isn’t anomalous. Bodies in Prison Pit are always gloriously messy, both in the sense of excreting-bodily-fluids-and-coming-apart-in-hideous-ways and in the sense that they are gratuitously indeterminately gendered. Thus, the three-eyed monster named Indigestible Scrotum sports not only his(?) titular spiky scrotum, but also what appears to be a vagina dentata (or whatever you’d call that.)

As this suggests, in Prison Pit, sexual organs are less markers of gender than potential offensive weaponry, whether you’re hurling monstrous abortions from your stomach cunt:

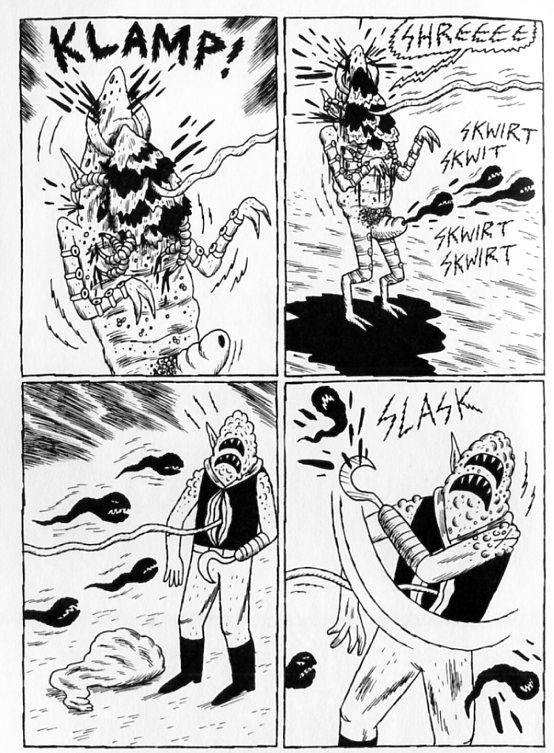

Or blasting monstrous sperm from your sperm-shooter

You could argue that turning sex to violence like this is just another manifestation of a denial of vulnerability, I guess…but, I mean, look at those images. Do those creatures look invulnerable? Or do they look like they’re insides and outsides are always already on the verge of switching places?

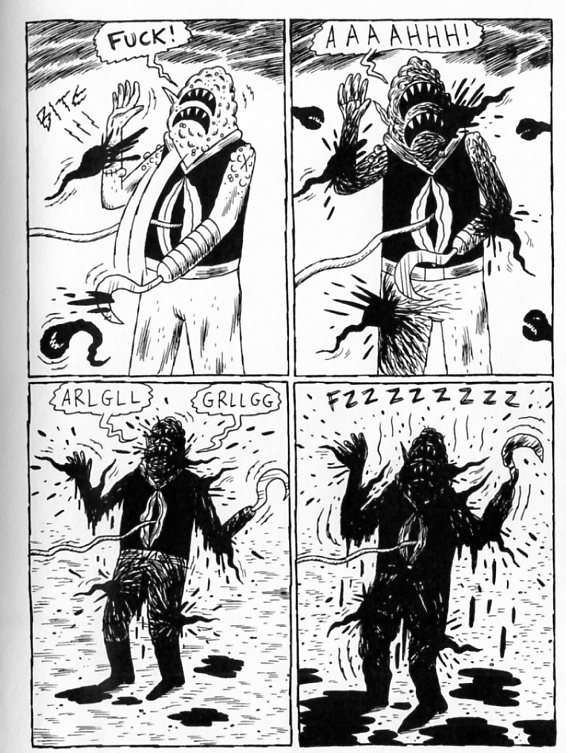

This is, perhaps, Marlowe’s hyperbolic anxiety come to life; sex as body-rot and degeneration; desire as a quick, brutal slide into chaos.

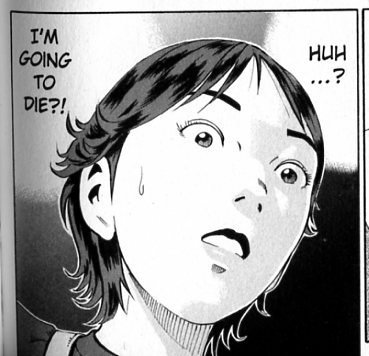

It’s telling, I think, that the one actual act of sex in the first four volumes is a multi-level rape. The protagonist has his body taken over by the slurge — that repulsive creature attached where his left arm used to be. The slurg-controlled body is then kidnapped by another (male? genderless? neuter?) antagonist, who fits him (it?) with a mind-control computer helmet and cyborg penis.

The mind-raped protagonist is then commanded to rape the Ladydactyl, a kind of monstrous feminine flying Pterodactyl.

The robot-on-atavistic-horror intercourse produces a giant sky cancer which tears the Ladydactyl apart. The protagonist finally regains his own brain, and declares, “That fucking sucked.” Which seems like a reasonable reaction. Rape here isn’t a way for man to exercise power over women. Rather for Ryan everybody, everywhere, is a sack of more or less constantly violated meat, to whom gender is epoxied (literally, in this sequence) as a means of more fully realizing the work of degradation.

In Prison Pit, Marlowe’s signal virtues of honor and continence are impossible. And, as a result, Marlowe’s signal failings — fear of bodies, fear of losing control, misogyny, homophobia — rise up and vomit bloody feces on themselves. Whether this underlines Chandler’s ethics or refutes them is perhaps an open question. But in any case, it’s enjoyable to imagine Philip Marlowe dropped into Ryan’s world, his private dick torn out by the roots to expose, quite publicly, the raw, red, gaping, and ambiguously gendered wound.