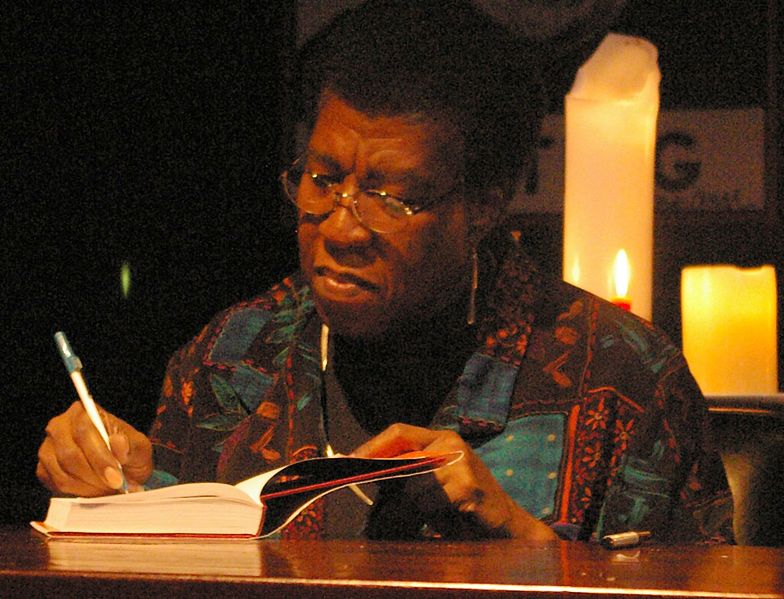

[Note by Noah: This is an excerpt from a story by Walidah Imarisha which will be included in the anthology Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories From Social Justice Movements, edited by Walidah Imarisha and Adrienne Maree Brown. The book is a collection of sci-fi stories by social activist writers, inspired by the work of Octavia Butler. The editors are currently running a funding campaign on indiegogo, where you can find out more about the project.

Thanks to Walidah and Adrienne for running this excerpt here!

Octavia Butler

… The gang stayed for a few hours, drinking copious amounts of whiskey and making more noise than the rest of the bar put together.

Finally they started to trickle out. Tamee, who had to take a piss, was the last one out. He walked down Lennox on unsteady legs. Night still warm from the summer’s day heat, like the hood of a parked car. He looked up at the moon. It was blood red. Damn, Tamee thought. Rubbed his head. His fingers tracing the uneven scar that ran from the top of his cranium, down the right side of his forehead. Crossed the socket where his right eye used to be. Ended an inch or so under his bottom lid. Like a permanent tear.

The doctors said he was damn lucky. If his head had been turned just a few degrees up, it would have penetrated his brain. If it didn’t kill him, it would have left him a vegetable.

This is why you don’t try to take on five nazi skinheads all by yourself, he mused ruefully to himself. Especially not if one of them has a crowbar. His mother always said he was stubborn as a mule and had to learn everything the hardest way possible.

As if called into existence by his thought, Tamee caught sight of a nazi he knew sauntering on the other side of the street. Tamee didn’t know his real name, only knew the bonehead went by Joker. Tamee had had a number of run-ins with Joker and his crew. Tamee had come out the worse for wear on most of those too.

But not tonight, he thought grimly. Cracked his knuckles. Tonight was payback night.

Tamee started loping across the street after him, his long legs gazelle-like in their movements.

“Hey fuckwad!”

Joker’s turning face smashed into Tamee’s fist. Blood rained on the ground. Tamee hit him with a flurry of punches. A knee to the gut. Threw him up against the wall. Another combo to the face.

Tamee was so intent on administering the beating, he didn’t hear Joker’s three man crew approach from his right side. His blind side. And he was blindsided. A fist slammed into his skull right behind his ear. He didn’t see stars; he saw a nuclear bomb explode behind his eyelids.

The four nazis circled around Tamee. Boots fell like autumn leaves. Tamee was protecting his head, his face, his internal organs. But not for long. He knew they were just getting started. He wouldn’t be able to hold out long. Tamee could tell they didn’t mean to leave anything of him when they were done.

Just when Tamee felt his consciousness begin to slip away, A. rounded the corner. She stopped, took a couple seconds to assess the scene.

“Hey, get out of here! Get out of here, black bitch, if you know what’s good for you!’

A.’s eyes smoldered, but she turned to leave. Her eyes caught Tamee’s. His desperate, terrified, hopeless eyes. She had seen that look so many times before. That look had gotten her kicked out of heaven. That look had cost her everything. She would have nothing to do with that look.

But the nazis took her moment of reflection for defiance. Three of them peeled off. Menaced towards her. Circled her like jackals. One of them pulled out a knife.

“You shoulda left when you had the chance, bitch.”

She locked her eyes on them. She knew they couldn’t seriously injure her. They didn’t have the power. But they could hurt her. And she’d felt enough pain for three lifetimes.

And she just really really hated boneheads.

With one fluid motion, A. whipped her trenchcoat off. Her remaining wing was wrapped across her shoulder like a shawl. Tied down by a cord wrapped firmly around her waist. She ripped the cord free, and her wing, black as the night’s sky, snapped back and out with a five foot span. Reaching for the lost heavens.

“What the fuck???” The closest nazi to her scrambled backwards.

“Man, it’s kind of costume or something. Don’t be fucking stupid!” Joker yelled. “Fuck her up!”

The nazi nodded and charged A. She jumped in the air, flapping her wing while she did. She could not fly with only one wing, but she could jump much higher than humans, and descend slowly.

The nazi ran right under her, carried by his own momentum. As he passed, she kicked him with a boot to the back of his head. He sprawled on the concrete like split milk, unconscious.

She made short work of the other two who bellowed and ran at her, enraged. An elbow to the face. Flurry of punches. Broken nose. Blood. Silence.

Joker stared at her. Fear and loathing mixed in his eyes. He looked about to rush her. But he must have calculated his odds because instead he turned to run. A. leapt forward. Wrapped her wing around him. Squeezed. Squeezed until he stopped struggling and slumped to the ground, breathing shallowly.

She surveyed the five men sprawled on the ground, the nazis and Tamee, who had uncurled himself from a ball but had not moved during the fight. Frozen with amazement and awe. He felt absolutely no fear. He knew he was in the presence of something incredible. Exalted. Divine.

She looked down at Joker. She should just leave them all here for the cops to find and be done with it. This wasn’t her problem. She wouldn’t have gotten involved if they hadn’t pulled her into it. She shouldn’t have gotten involved at all. Why the fuck did she? she asked herself, disgusted. She glanced at Tamee, the cut on his forehead leaking blood into his good eye.

A. sighed. She had lived in Harlem long enough to know sending anyone into the criminal justice system did nothing but make them more damaged and desperate. She hid in the shadows, watched the police patrolling the streets. Not patrolling. Hunting. There was no mercy behind those shining badges. The scene played out over and over like a flickering film projected onto the city. And she had done nothing each time before, just waited for the reel to end.

She knelt down next to Joker. Like this, he looked so fragile. So breakable. She could end this right now. Do to him what he had planned to do to Tamee. She was an Angel, after all, even if she was fallen – she would be merciful.

A small voice in the recesses of her mind asked, Should I use the Voice? She stared down at this manchild she knew to be a killer. She could smell it on him; this was not his first attempt at taking a life, nor would it be his last if something wasn’t done. She shook her head, trying to clear the thought out, but it clung like a burr.

When she was an Angel, A. had used her Voice to change hearts. Sing humans good. There were no repercussions as an Angel, with a sanction from the Almighty. It had actually been a joyous communion, and the glow she felt had filled her with even more warmth and peace than she thought possible.

But God had taken that when he set fire to her and expelled her from Heaven. Sure, He had left her the Voice. But if she used it, she took on these humans’ pain. She had tried it only once, when she was first exiled. It was flames of the barrier between Heaven and Earth licking at her flesh again, biting and tearing until she could not take it. She had collapsed; it took days to recover fully. One of the many reasons she avoided interacting with humans when at all possible. She’d already suffered enough pain for them.

But now that this situation stared her in the face, she found she could not just walk away. Even though everything inside her screamed to. She could not shake the look in Tamee’s eyes, the plea for help. Mercy. Grace. It had been a long time since she had been reminded not only of the horror of humans, but the vulnerability.

A. opened her mouth. She began to sing. It was the most incredible sound Tamee had ever heard. Cool clean waterfalls cascading down into cool green valleys, his mother’s hands cool on his hot forehead, the beauty of a grove of olive trees bright in the sunshine in his stolen home of Palestine. His whole family, even the ones murdered and lost, gathered, arm and arm. Complete peace.

A golden light shone in A’s mouth, illuminating through her flesh. She leaned over Joker. The light cracked and rained down on his face. Soaked into his skin. At the same time, a murky darkness crept up the stream of light. Climbed into A. through her mouth. Darkened the glow emanating from her chest. She grimaced and her voice faltered, but she continued singing.

Joker’s face, twisted with hate and rage even when unconscious, began to relax. The lines of anger smoothed out. His face became serene. A child curled up in the arms of its mother, protected and safe.

A. turned and did the same to the others. The light in her chest almost entirely eclipsed by the smoky darkness from their mouths. She could barely reach the one furthest away, had to drag herself over, still singing but now her voice sounded like a small wounded animal.

When she finished with the last one, she leaned backwards. Wavered like a candle in a strong wind. She keeled over, her head hitting the ground with a sickening thud.

Tamee rushed forward to lift her up, despite the many injuries that screamed at him.

“Are you all right?” he stared down into her face. The color of coffee beans dusted with rose petals. Flawless like glass. Eyes like galaxies.

She was more beautiful than anything he could have ever imagined.

Her eyes focused on him. She jerked away and tried to stand up. She failed, and only accomplished rolling away onto her side.

“Get off.” Her voice, though thin, was infused with steel. Reached out her hand to try to lift herself up.

“I… I can’t believe you’re here. You exist. I never thought I would see something… someone like you…” Tamee sputtered.

A. gave up trying to stand. Laid there breathing shallowly for a while. Reached into her trenchcoat pocket. Pulled out a cigarette.

“So you think you know what I am.” The snap of the lighter.

“Of course I know what you are.” A touch of awe in his voice. “It’s been a minute since I touched the Qu’ran. Years since I went to masjid. But I would know you anywhere.

“You’re an angel.”

She paused, the look of pain on her face completely unconnected to her injuries.

After a long minute, she growled, “I used to be an Angel. Now I’m just like all of you. Scraping away on the face of this cesspool called a planet until you fucking die.”

“Wow… um, okay,” Tamee stuttered.

Silence. Her ragged exhale.

“Well, thanks. For saving me. I mean. I really appreciate it. Really,” he babbled.

“Don’t thank me.” Her tone stung more than a slap to the face. “If I’d had my way, I wouldn’t have done shit.”

Tamee was a little taken aback by her callousness. She didn’t sound much like an angel. For one thing, he had not imagined an angel would curse. He thought there would be more love and compassion. She wasn’t really at all how he imagined an angel.

She was a million times better.

A. reached into her pocket and pulled out some more black cord. She propped herself up against the brick of a building. Gingerly folded her wing forward across her shoulder. Began wrapping the cord around and around, until the wing was strapped down securely.

“So, what’s your name?” Tamee asked after a minute.

“Don’t have one.”

“Well, what did they call you back then? In… you know, in Heaven?”

“Nothing. Angels don’t have names. We know each other. We can… “

A. had no words to describe the flow of energy. The connected contentment that linked all of the Angels. God. Heaven itself. They were all one. Separate and one. There was a me, but there was no you. Everything was felt. A continuous feedback loop of perfect joy. There were no human words to describe it, because they could not even fathom the depths of beauty that come from being part of God. It made her angry to try to find words to explain the most painful loss she would or could ever have.

A. barked, “ We just feel each other, okay.”

“Okay, can I just call you Angel then?”

“No.” She threw her trenchcoat over her shoulders as she staggered to her feet. She began dragging herself away. Tamee sat, frozen, wanting to yell for her to wait, wanting to say something, anything, that would make her stay. Make her turn around so he could see her face one more time. But he could think of nothing. His heart contracted in his chest as he watched her limp away.

She stopped, hand on the dirty brick beside her. She turned her head slightly to the right. Enough for him to see her face in profile.

“You can call me A.

“Ain’t no Angels in Harlem.”